How is St. Louis going to grow again? If it is to grow, where could this happen? There’s a significant amount of construction happening in the city, perhaps more large multi-family projects and single-family rehabs than we’ve seen in half a century. Still, resistance to growth can be found just about everywhere.

In a city that has lost more than 60% of its peak population (SIXTY PERCENT!), one might assume that there would be a widespread thirst for development. But a funny thing has happened, residents have become used to decline, comfortable with it, even in favor of it, whether they admit it or not. County municipalities are in a state of denial regarding population loss. “It’s just a blip! We added a Menards,” they say, no matter what the Census shows.

Opposition to development can be found from Frontenac to the edges of Forest Park, from Shaw to The Hill, in places that are more or less holding their own, and those that continue to see significant population loss. We can’t hope to address changes in population everywhere across the metro area, but the city and many suburbs share certain traits.

St. Louis at 400,000. This was the population of the City of St. Louis in 1990. We’re suggesting this be the goal for city growth, the number, however arbitrary, that should guide development planning and proposals to revitalize the city. So what would it mean for St. Louis City to gain about 85,000 residents? What would that look like?

One convenient example is the proposed development for The Hill neighborhood. The project by the Sansone Group would add as many as 450 living units at the southeast corner of this south city enclave, replacing a long vacant 10-acre industrial complex.

This project has been met with immediate opposition for being too big, for being out of character for the neighborhood. The plan presented includes single-family homes along Hereford Street, and the restoration of some portion of the warehouses facing Daggett Avenue. A six-story apartment building would be tucked behind, against railroad tracks and warehouses.

The project, if built as proposed, might return The Hill to near its 1990 residential population. There are currently at least 528 fewer residents in The Hill than 26 years ago, an 18% decline. Eleven percent of housing units were counted as vacant in the 2010 Census.

{the Flynn property on The Hill – proposed for 450 living units}

{the Flynn property on The Hill – proposed for 450 living units}

The Hill is a wonderful neighborhood. It’s also not exempt from the challenges facing other neighborhoods, the city and region. The Hill cannot support its businesses as it continues to lose residents. Losing residents increases traffic as businesses must court and rely on patrons driving to the neighborhood.

We all want amenities near our homes that attract as few others as possible to stay viable. Increasingly, people want to drive to walkable commercial districts. These issues are at the core of the growth dilemma. Control of development exists at such a micro-level that these opposing desires have long dictated planning.

More than a couple examples:

Some residents of up-scale Frontenac successfully opposed the development of a retirement community on the site of a vacant school. That project was likely to bring no more traffic to Clayton Road as the school produced for years. The project is very near the upscale Plaza Frontenac mall, though no one seems concerned with the traffic such a shopping destination produces. Brio opens a new restaurant? No problem. Starbucks, yeah, we’ll take that.

The city of Kirkwood bought serviceable commercial buildings for $1.43M in its downtown in 2011 to demolish for 46 parking spaces. They’re convinced that the future is providing parking for those who want to drive to a walkable downtown.

In the city’s Central West End, residents concerned with parking forced the developer of the mixed-use tower at Euclid and Lindell to spend perhaps as much as $2.5M more on an additional level of subterranean parking than had been required. They’re convinced that adding more parking will reduce traffic.

In the city’s Dogtown neighborhood just south of Forest Park, neighbors objected to a proposed 63-unit apartment building on the site of a vacant lumber yard. Proposed in 2012, the site remains vacant. A lawsuit was filed to block the development. Their demands? An all-brick building and more parking.

In The Loop, although tax revenue is at an all-time high, and vacancy at near zero, University City and Loop businesses believe a lack of parking is harming the district. The solution? Millions in public money to build more parking. A large mixed-use development on a vacant lot near the MetroLink station east of Skinker was fast tracked, but also caught opposition from neighbors.

Richmond Heights recently saw a challenge to a now-approved apartment project that will replace a vacant school and church adjacent to an Interstate. The complaints? Too much traffic and the project being out of character with adjacent single-family homes. The outcry was notably different than when dozens of single-family homes were demolished for a Menards (which sits near both a Home Depot and Lowes, each in a separate municipality).

In Clayton, the city was pressured by residents in single-family homes to not approve a 45-unit townhome development at a vacant school building two blocks from MetroLink and a block from what will be a massive mixed-use Centene development. There is opposition to building four townhomes on a lot 1/2 block from the central business district, a ridiculous lawsuit nearly brought the apartment tower at 212 S. Meramec to a halt, and to preserve its views, Graybar opposed a hotel development, then bought the land and sold to a developer to build a six-story mixed-use project – equivalent in height to its pedestal parking garage.

It can seem that everywhere one turns development that would add density, that would support local businesses, and even decrease traffic, is being opposed.

There are several mathematical ways the city and other areas can grow. Family sizes can increase, living unit sizes can decrease, vacant parcels can become occupied, and existing development can be replaced by higher-density residential.

In reality, the city and other urbanized areas will grow by building upon their success. If the city had an official objective to add residents, to support small-scale local commercial districts, to increase retail density, perhaps development in the city would find some direction.

What if the Sansone Group, Alderman Vollmer, and residents of The Hill had some framework from which to base a preference for development at the vacant Flynn property? What if the city’s plan counted for something at the beginning of the process? What if unwritten rules were guided by written goals?

It comes back to the fact that we all want amenities near our homes that attract as few others as possible. While perhaps a natural impulse, it’s an impossible way to build a healthy city, healthy neighborhoods, and healthy businesses.

Without residential density, the requirement for parking to accommodate patrons arriving by car creates an environment detrimental to commercial activity. We create a place that is perhaps easy to get to but which isn’t worth arriving at.

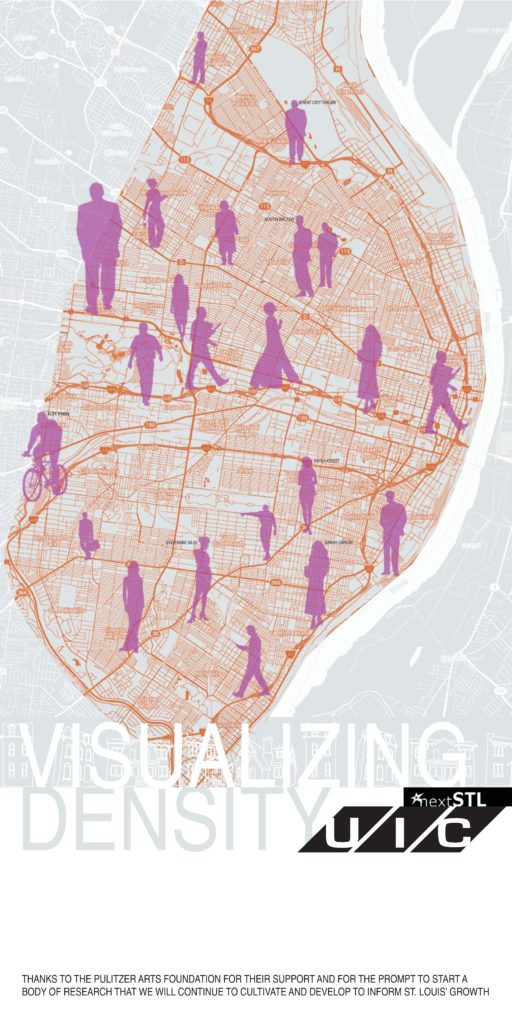

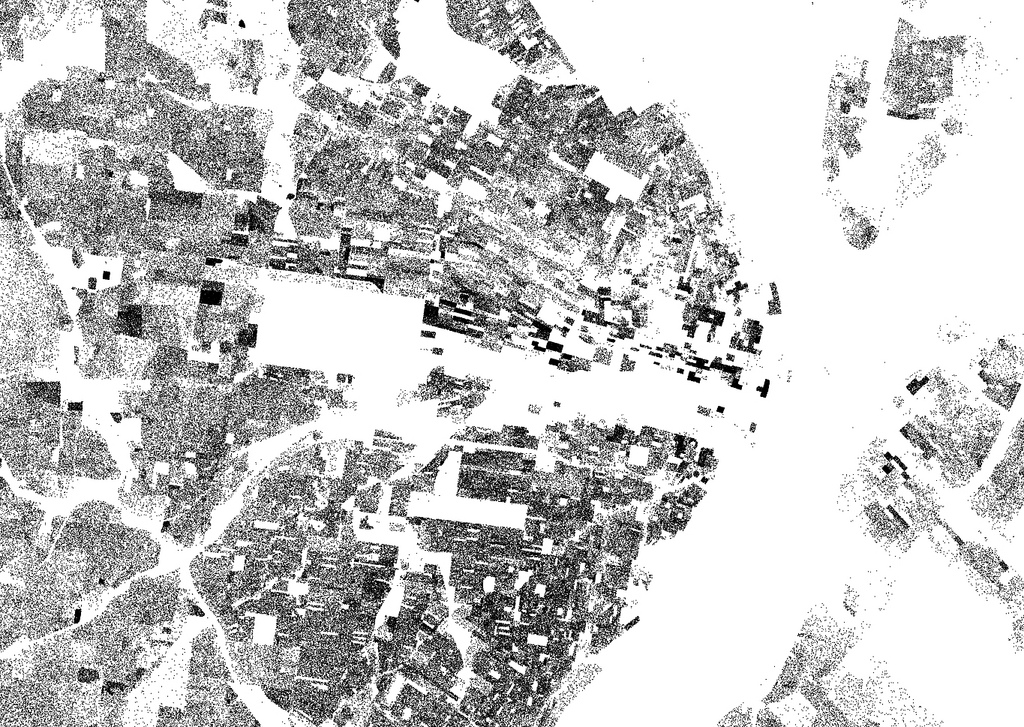

{one dot for each and every St. Louisan}

{one dot for each and every St. Louisan}

So how does the City of St. Louis add 85,000 residents?

The city invites added density at virtually every opportunity. When a proposal seeks to replace a vacant office building with 200 apartments, you approve it, perhaps even with subsidies, to aid your goal. When a 63-unit apartment building offers 63 dedicated parking spaces, you approve it. When 10-acres of abandoned warehouses attracts a proposal to add 500 residents, you approve it.

Such a stated development goal could also help frame what development isn’t wanted. Should a gas station replace three existing buildings? Should homes be demolished for parking for an expanded grocery store? Do these actions add to the residential base? Do they increase density?

Development isn’t that simple, but the premise and process with which it is evaluated can and should be. Instead of a developer guessing at what an individual alderperson, or other hidden power, may say, they should be guided by a city plan and written priorities.

This is highlighted well in the recently revealed St. Louis City Economic Incentives report. A main conclusion was that economic incentives should be targeted at a development goal, that St. Louis lacked clearly stated goals, and so it’s not possible to evaluate if the hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives were effective or necessary. We don’t know if they achieved any particular goal, because there are no particular stated goals.

It should be understood that residential density isn’t the end goal, but a city simply cannot support small scale, high-yield, sustainable commercial or office development without it. It must come first, it must be prioritized. Adding residents is the best way to support a vibrant place without increasing traffic.

Why doesn’t St. Louis City have any real retail density? It lacks residential density. Families aren’t getting bigger. Four-family buildings converted to two-family aren’t going back to four-family. We do have an opportunity, if guided by smart development principles, to add residential density, and therefore retail and jobs to the city. The question is whether we will do it and who will lead the way.

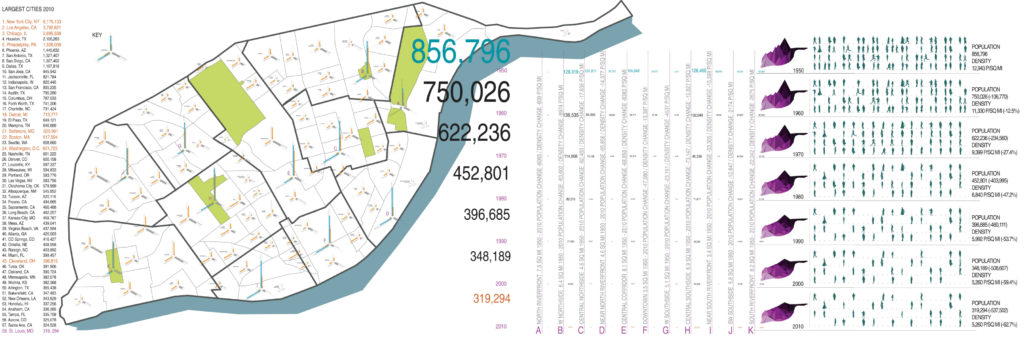

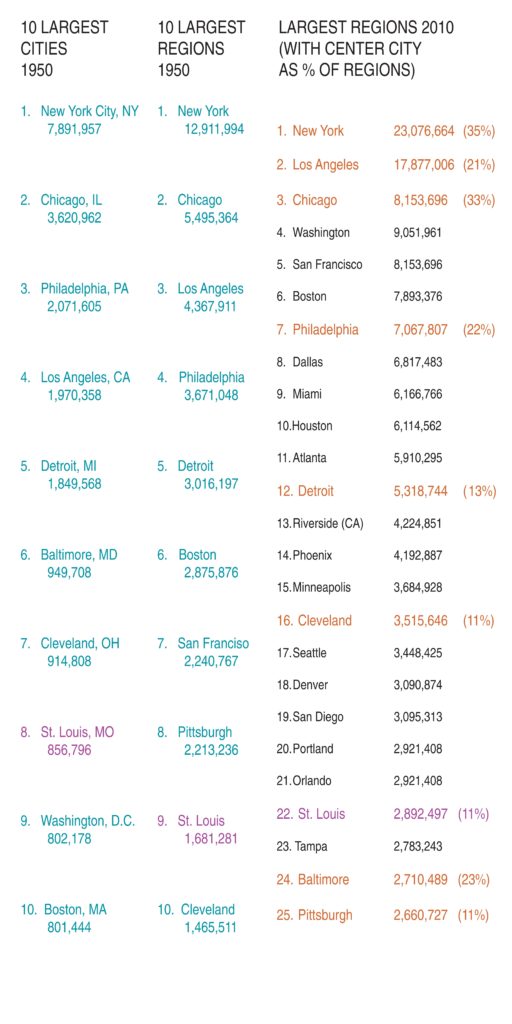

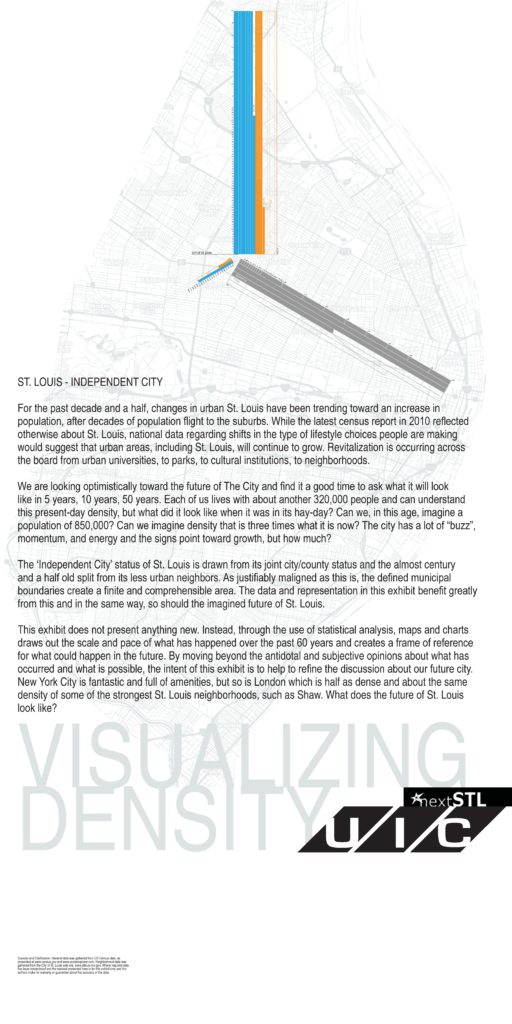

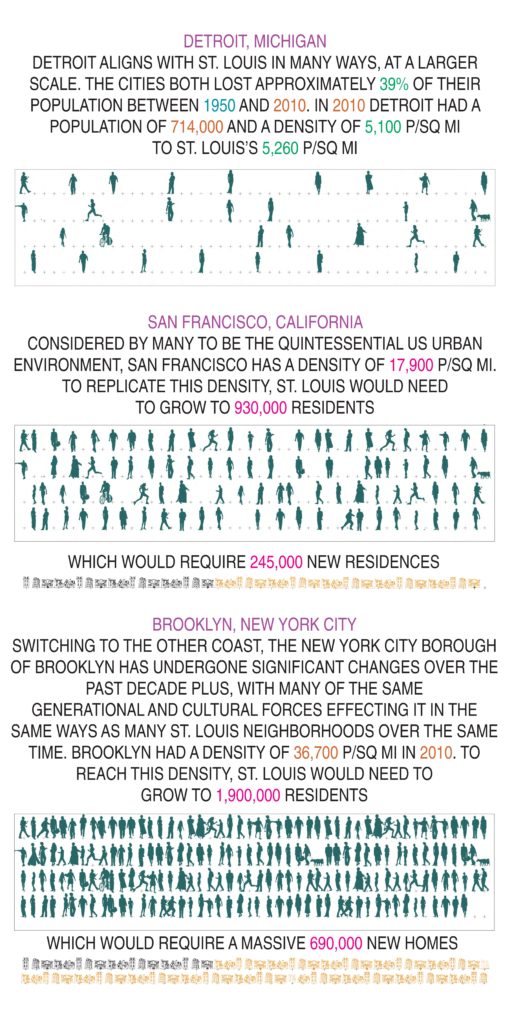

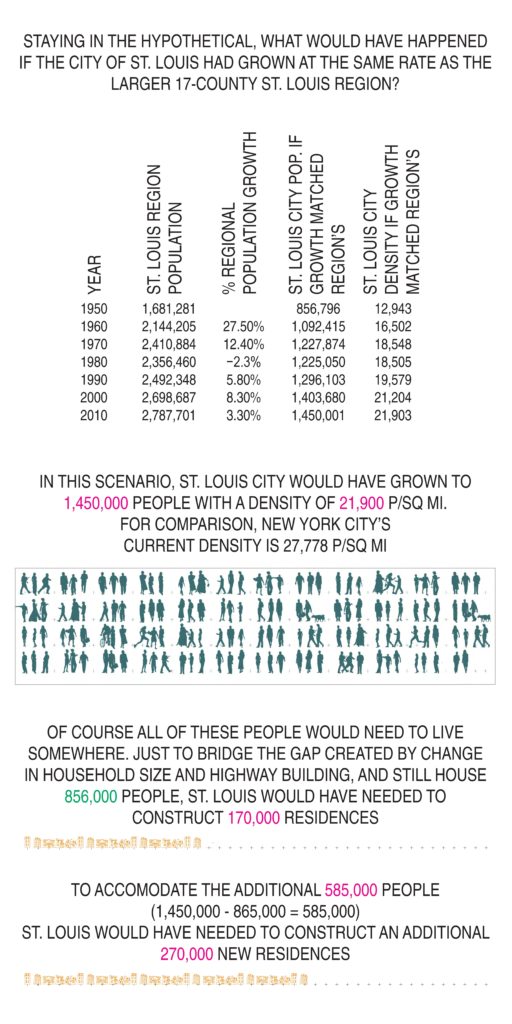

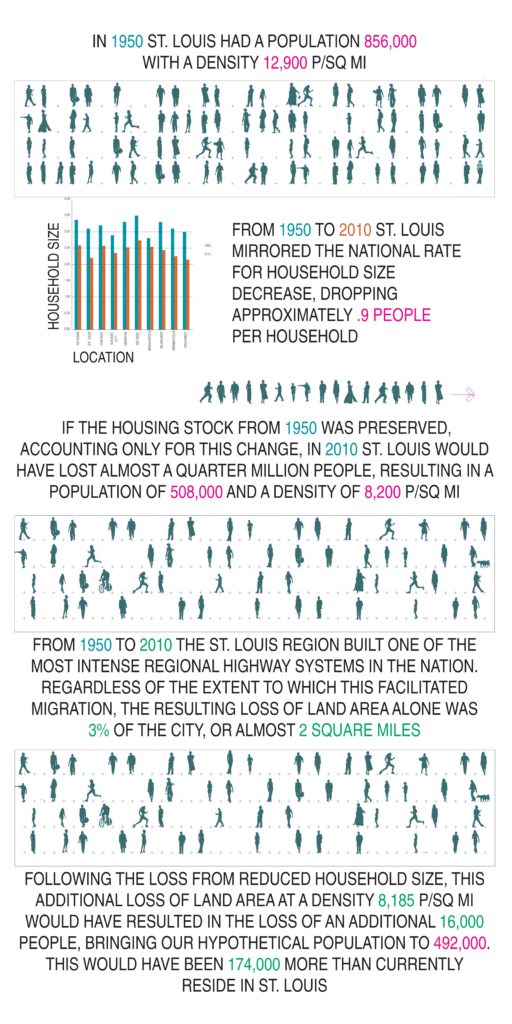

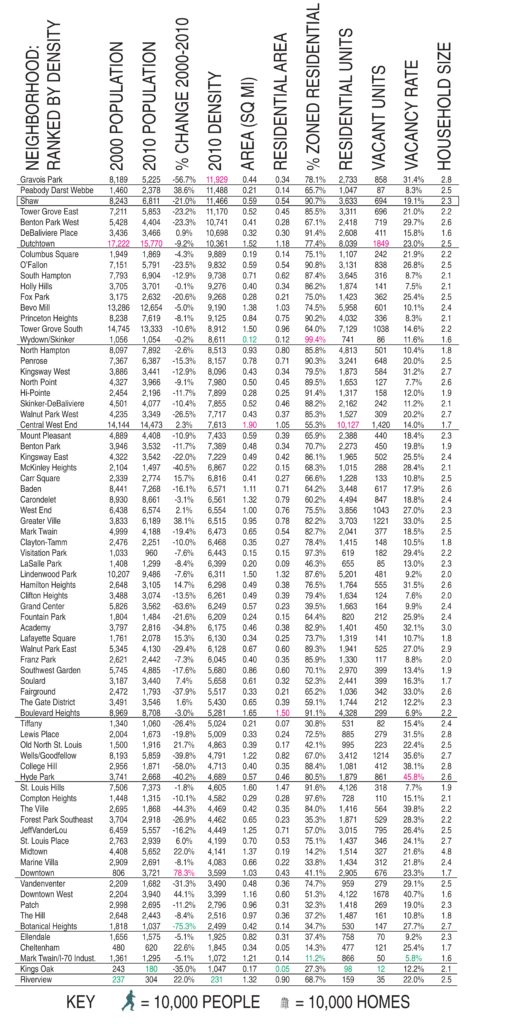

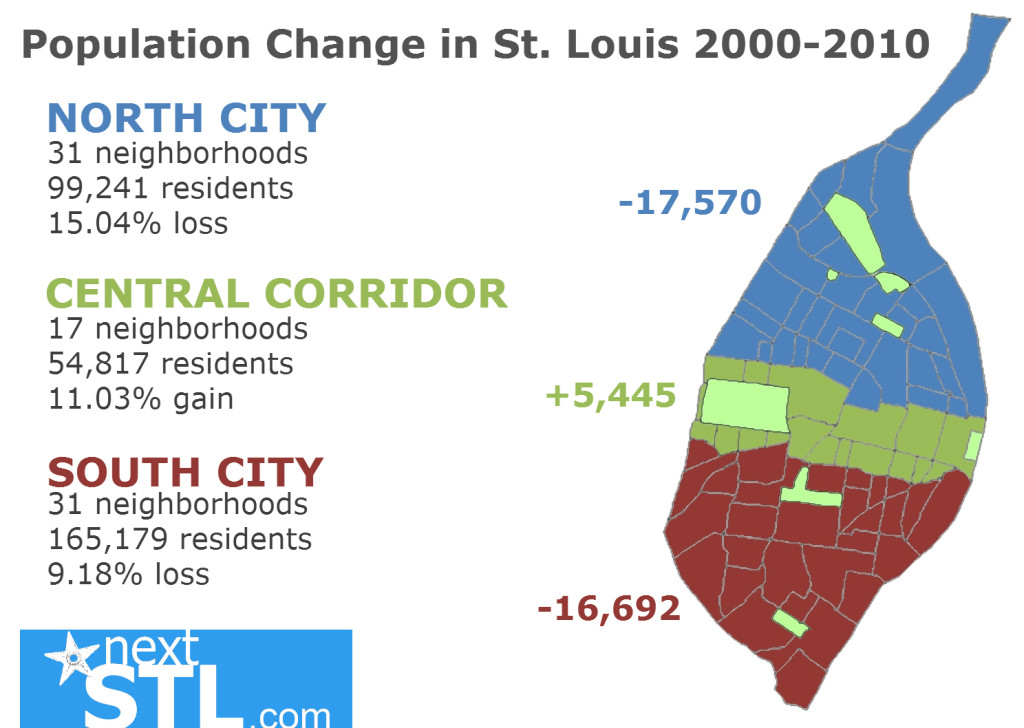

Along with UIC, we explored the issue of population decline as part of a PXSTL project: Understanding Population Change and Density in St. Louis (UIC & nextSTL @ PXSTL). Those boards are shown below: