Why does the City of St. Louis employ approximately 430 police officers per 100,000 residents? Perhaps the better question is: What factors lead the city to employ approximately 1,372 police officers?

Why does the City of St. Louis employ approximately 430 police officers per 100,000 residents? Perhaps the better question is: What factors lead the city to employ approximately 1,372 police officers?

From The Atlantic Cities: “One set of explanations, from the “functionalist” class, argues that departments staff up in relation to population density, or budget capacity, or the sheer quantity of crime. Then there is the class conflict theory: Widespread inequality forces police to beef up to protect the rich from the poor. And the race conflict theory: Law enforcement expands in response to the threat that minority groups pose to the majority.”

Now two University of Missouri graduate students think they’ve found a trend: Cities tend to increase their police force (counting full-time sworn officers) when they have high levels of poverty and broad racial economic inequality at the same time..

Guðmundur Oddsson, Andrew Fisher and Takeshi Wada looked back at police staffing levels from the year 2000 in 64 American cities with populations larger than 250,000. Their research was recently published in the International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy and is currently available only by purchase.

Reading the study, the following seems to succintly describe the findings: In cities with relative equality between Whites and Blacks/Hispanics the predicted relative size of police force decreases when the average poverty rate increases. In other words, wealthier cities are likely to have larger police forces. In poorer cities where the income distribution is more or less equal between racial groups, paying for police is not a budgetary priority. This finding is actually consistent with Sharp’s fiscal capacity hypothesis which claims that poorer communities are likely to pay less for police. That is, even when the income distribution is uneven, cities are less likely to increase their police forces if the population of poor is relatively small.

After initially posting this article, a couple Tweets from RJ Koscielniak caught my eye and seem especially pertinent to St. Louis and the part of the city most consider to be revitalizing. Taken in aggregate, “The Missouri study doesn’t take into account the privatization of police forces or ‘civilizing’ tactics separate from law enforcement. The size of the municipal police force is one node in the networks of discipline and security mobilized to protect cities. How do you ignore the trend of major urban institutions contracting private security services or developing dedicated police forces?”

Hundreds of millions of dollars are being invested in the City of St. Louis’ central corridor – a Mercedes dealership, Whole Foods, medical center expansion, more apartments and more retail. From the Highlands to Midtown, it’s clear things are changing. Much of these areas are policed by private forces, and/or greatly supplemented by off-duty police and other security, including the Washington University medical campus, the Central West End Neighborhood Security Initiative, Forest Park Southeast Supplemental Patrols (6,000 hours), Grand Center, Inc., and St. Louis University. It would seem that in a city like St. Louis, not accounting for this policing would obscure any conclusion based on the metropolitan police force alone. I’ve reached out to the study’s authors for comment.

I wrote the following in an article titled “Is the City of St. Louis a Safer Place in 2011 than in 1971? How Are We Supposed to Know?“:

Another question may be whether the City of St. Louis has the right number of police officers. A quick look reveals some variation in the number of police officers per resident across American cities. St. Louis employs 1,372 police officers, or 430/100K residents. Baltimore: 3,100 – 499/100K. Philadelphia: 435/100K. Boston: 333/100K. Memphis: 317/100K. Detroit: 388/100K. Charlotte: 230/100K (these numbers were updated 1/19). The more interesting question would be how the number of officers per resident has, or has not, changed over time.

Notably, as the Atlantic Cities states, “It’s unlikely that city or police officials are looking at these two data points – the prevalence of poverty and the extent of economic inequality between racial groups – to calculate departmental resources. It’s more likely, Fisher says, that police are responding to the presence of crime or the perception of fear that’s attributable to the intersection of those two trends.” The city is set to control its police force for the first time since 1861. This will allow the city to more efficiently consider everything from patrol patterns to staffing levels.

A fuller explanation from the study’s authors:

Cities with great economic inequality between racial groups will not strengthen their police force if poverty is minimal because less prosperous groups pose little threat to affluent groups if few live in poverty. Cities with great poverty will not heighten policing if economic inequality between racial groups is negligible because less prosperous groups do not threaten more successful groups if economic disparities are small and poverty is widespread. However, cities with high levels of poverty and great economic inequality between racial groups will enhance their police force because affluent groups are threatened by groups that are worse off when economic disparities are pronounced and many live in poverty.

We’ve covered issues of crime in various ways at nextSTL. Here are a few select articles for further consideration:

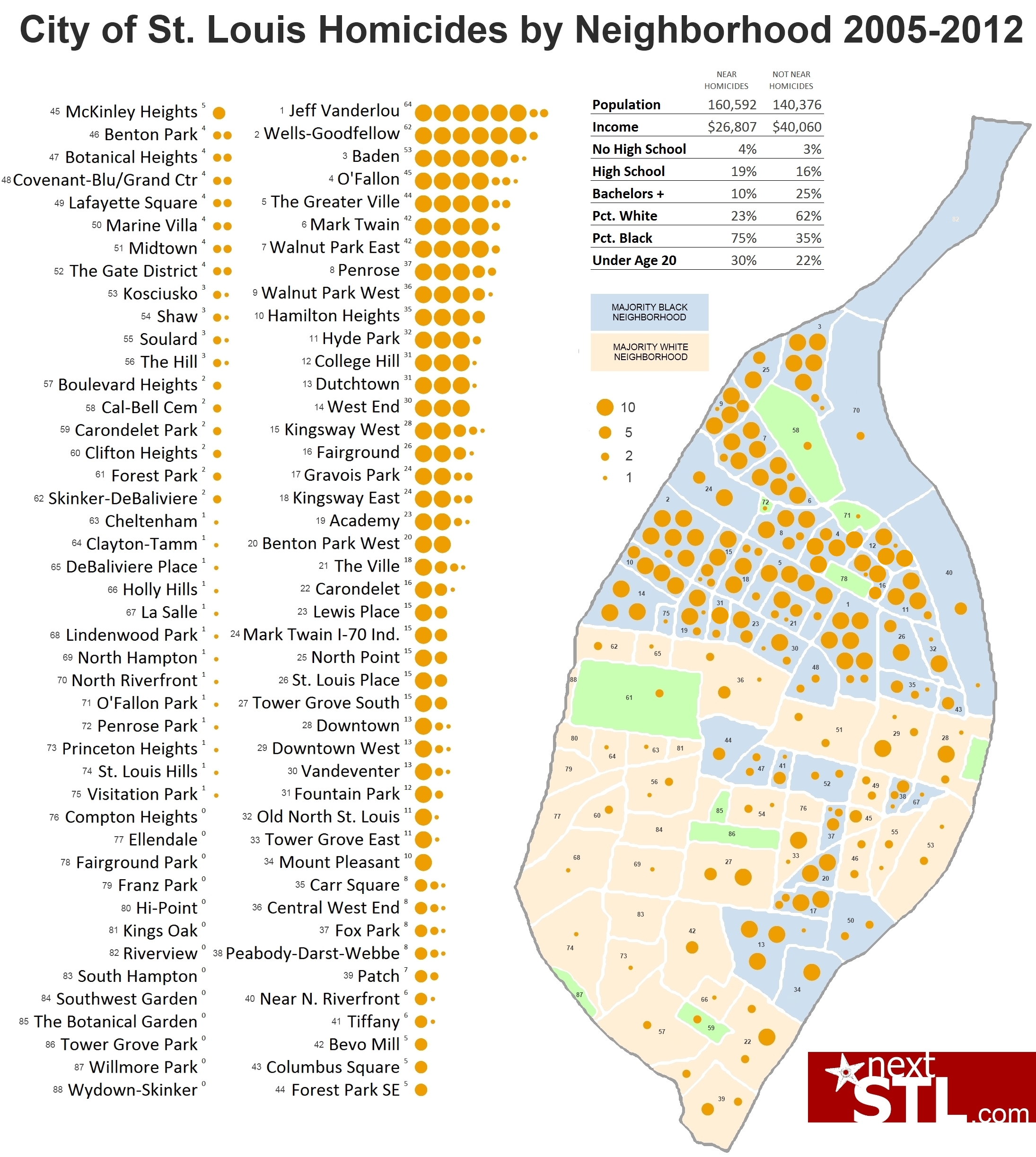

Understanding St. Louis: Total Crime Index, Violent Crimes and Property Crimes in City Neighborhoods

Understanding St. Louis: Homicide and Index Crime Totals and Rates 1943-2012

Understanding St. Louis: The 12 Neighborhoods of the 30-day Anti-Crime Initiative

What’s Wrong with Calling St. Louis the Nation’s Second Worst City for Crime? This:

From the Nation’s “Most Dangerous” City: St. Louisans Say They Feel Safe Walking Alone at Night

The St. Louis Metropolitan Region: Safer Than Santa Fe (and 101 Other MSAs)