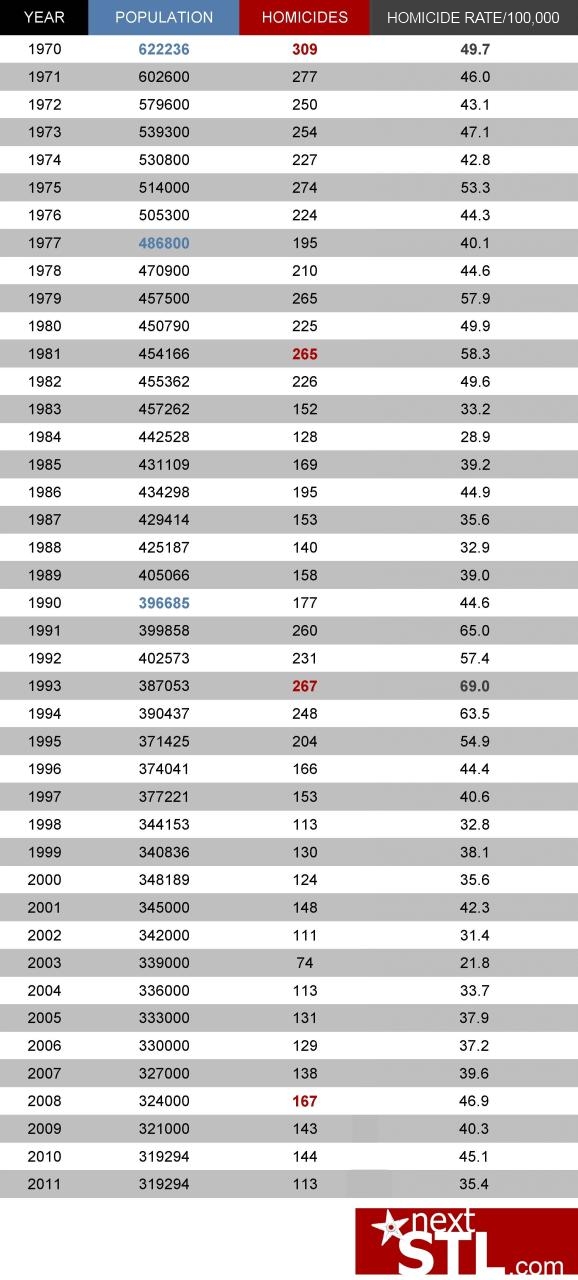

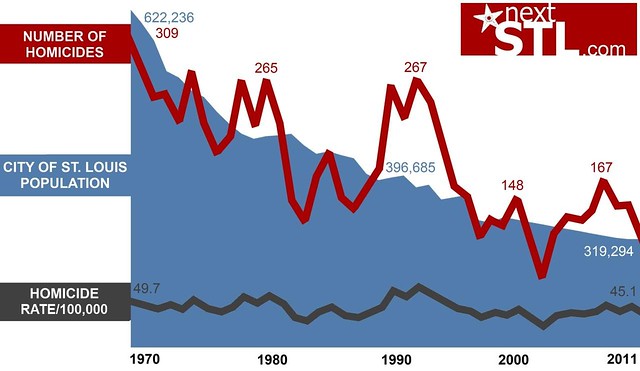

The question seems simple: is the city of St. Louis becoming a safer place? Recent reports would have you believe it is. "Police and crime-fighting organizations around St. Louis are claiming a big victory," begins a story by KMOV. For 2011 the number of homicides in the city decreased by 22% from 144 in 2010 to 113. (no explanation has been provided for why the story stated a 30% drop. We're guessing a mathematical error.). This is a good thing. But take a step back, glance at the larger trends, ask a few questions, look for additional context, and the story becomes much less clear.

The number of homicides in St. Louis has been trending lower for decades. The urban crack cocaine epidemic of the early 1990's being the greatest outlier, there's significant consistency in the trend. Has the city of St. Louis gradually become better at fighting crime? Every drop in crime is met with claims of better, smarter crime-fighting. Again from the Post-Dispatch regarding 2011, "a new approach – using all facets of the justice system – is showing serious success." When crime goes up? From coverage of a spike in homicides in 2008, "Homicides do tend to go up in an economic downturn," stated a criminologist. One resident said he was told, "there was nothing (the district police commander) could do to protect us and the community … that he didn’t have the manpower." At the time, a North Side alderman implored, "the community has to be ready to defend itself."

Are we to believe that an increase in crime is the product of forces outside our control and that of the police? Are we to believe that a decrease in crime is the result of smarter crime-fighting? Using the homicide rate as a benchmark, St. Louis is basically the same city it was in 1971 when the city had 602,600 residents and 277 homicides. Would it be a mistake to conclude that the most significant factor in the number of homicides in St. Louis has been the number of residents?

Shouldn't the homicide rate, and that of other serious crimes, not just the raw numbers, have fallen farther? The crime rate for serious crimes has fallen dramatically across the country over the past two decades and is at its lowest rate since 1963. The murder rate has dropped by almost half, from 9.8/100,000 in 1991 to 5/100,000 in 2009. Over the same time period, the rate has dropped from 65 to 40.3 in St. Louis. Have other communities simply been quicker to use "all facets of the justice system"?

Another question may be whether the City of St. Louis has the right number of police officers. A quick look reveals some variation in the number of police officers per resident across American cities. St. Louis employs 1,372 police officers, or 430/100K residents. Baltimore: 3,100 – 499/100K. Philadelphia: 435/100K. Boston: 333/100K. Memphis: 317/100K. Detroit: 388/100K. Charlotte: 230/100K (these numbers were updated 1/19). The more interesting question would be how the number of officers per resident has, or has not, changed over time.

While the long assumed direct correlation between poverty and crime has not been confirmed in the current economic downturn as many had anticipated (see 2008 comment above), evidence still suggests a positive relative relationship between economically depressed neighborhoods and high crime rates. Can the City of St. Louis, with a poverty rate of 27.8% be expected to have the same homicide rate while employing the same number of police officers as Charlotte, a city with a poverty rate of about 15%? What about Baltimore with a poverty rate of 21% and nearly twice the number of officers per resident?

For much of the past decade, it appeared that the homicide rate was in constant decline. Homicides were relatively low by historic standards and we were consistently told that the 2000 Census count of 348K residents was the low-water mark for the city. St. Louis was growing. You use decreasing homicides and increasing population and voila – a safer city. In reality, the city was still losing residents. A recalculation shows that 2008 and 2010 offered the highest homicide rates in St. Louis since the height of the crack epidemic in the early 1990s.

24/7 Wall St., a link-bait site we won't link to, recently ranked "The 10 Worst Run Cities in America". St. Louis appeared at no. 7, but was then described in a somewhat favorable light. "St. Louis has had a hard time controlling violent crime. With 17.47 incidents per 1,000 residents in 2010, the city has the second highest rate of violent crime in the country. This is due in part to the city's high poverty rate of 27.8 percent and its median income of $32,688, which is the 10th lowest out of the 100 largest cities. Additionally, nearly 20 percent of housing units in the city are vacant. All of these measures influence government revenues. Despite this, St. Louis has managed its finances fairly well." Perhaps St. Louis is doing ok given the challenges faced?

Of course there are other issues at play in St. Louis, where the city has not controlled its own police force since the Civil War. Besides being a bit of odd trivia, there are practical implications to crime-fighting. The Post-Dispatch recently found that St. Louis police officers fire their weapons up to three times more frequently per violent crime than officers in many other big-city police departments. Given the higher rate of violent crimes, that's a lot of shots – 117 incidents over the past five years, according to the P-D. An opaque, internal process has cleared 112 of those as being justified. If police officers firing their guns more often resulted in less violent crime, why hasn't there been more success in St. Louis? Is an officer's weapon considered a facet of the justice system?

We'll leave the unanswerable question of whether St. Louis is one of the worst run cities alone for now and return to the equally unanswerable "why has crime decreased in St. Louis and why less than in other cities"? Fewer homicides is good. If the current rate of decrease can be maintained, if St. Louis experiences fewer than 100 in 2012 and a new smarter, community supported, crime fighting culture can emerge, then we'll have a victory.

Looking at the national trend of decreasing violent crime rates, criminologists cite the following as primary factors:

- Increased incarceration, including longer sentences, that keeps more criminals off the streets.

- Improved law enforcement strategies, including advances in computer analysis and innovative technology.

- The waning of the crack cocaine epidemic that soared from 1984 to 1990, which made cocaine cheaply available in cities across the US.

- The graying of America characterized by the fastest-growing segment of the US population – baby boomers – passing the age of 50.

It's tempting to list all the crime-fighting efforts employed when the violent crime rate drops. Police are targeting "hot spots", judges are taking a tough stance on crime, homeowners are spearheading local efforts. All are true and everyone engaged in combating crime, from police officers to someone dialing 911 should be encouraged and applauded. Nothing is so public and private as crime-fighting. Yet few cause-and-effect relationships are so cloudy as crime and crime-fighting. Are we to hope for better economic times? A gentrified city? Ever more effective crime-fighting? Police firing their weapons even more often?

Is the City of St. Louis doing an effective job reducing violent crime? When indexed to national trends: no. When we attempt to put it in context: who knows. But as an empirical question, "is the city a safer place than four decades ago?", it appears that little has changed.