Many people know of Robert Moses, the urban planner in New York who changed the city’s landscape by razing historic neighborhoods and constructing urban highways and large monolithic apartment buildings in upper Manhattan, but many are unaware of his St. Louis contemporary. While Moses was clearing out the historic neighborhoods in New York, Bartholomew was at work in St. Louis, helping to shape the region as we see it today.

Harland Bartholomew was born in Massachusetts in 1889, and began his career as an urban planner in Newark, New Jersey, in 1911. In 1916, he came to St. Louis as the city’s first full time urban planner, a position which he held until 1950. The man who brought him to St. Louis was Luther Ely Smith, who would later be the man who envisioned the Arch grounds as a national park.

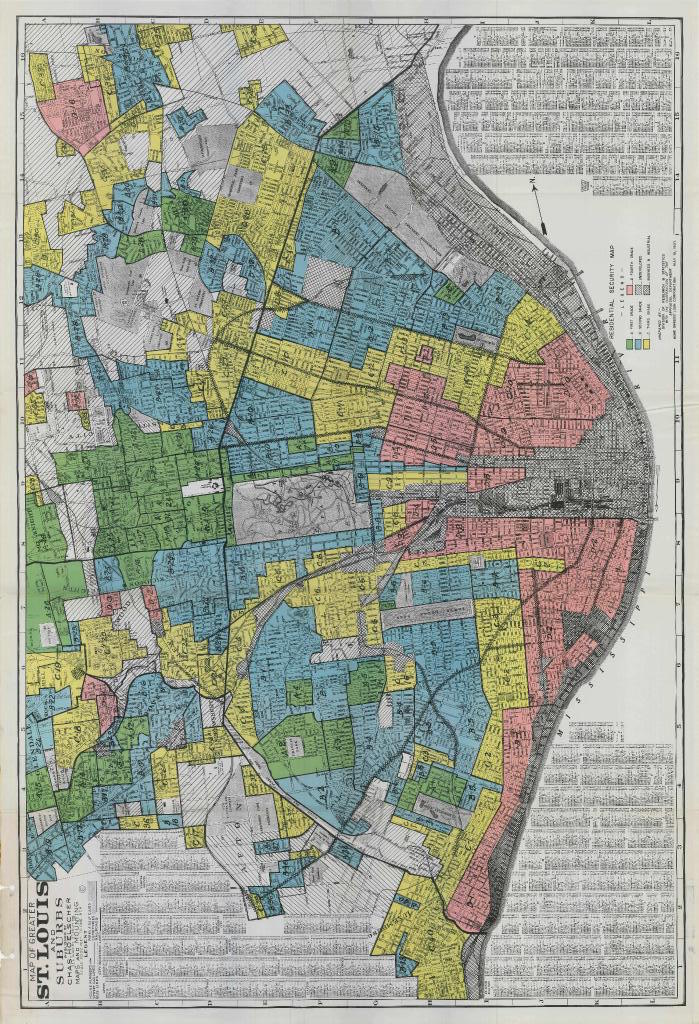

In 1916, shortly after the arrival of Bartholomew, the city of St. Louis enacted its first zoning ordinances. Bartholomew began to lay out the city for the automobile. At the same time, the city was experiencing a significant growth in its African American population, as many of them were fleeing the South to seek opportunities in the North in a move known as the Great Migration. This prompted the city’s white residents to call for segregation, and one of the first tools used to enforce the segregation was the zoning ordinances in 1916, which mostly kept African Americans confined to the Mill Creek, Ville, and Gate District neighborhoods, as well as a few other areas around the city.

In the 1920s, St. Louis had a campaign to widen its streets. Many of the notable thoroughfares, such as Gravois, Tucker, Olive, Lindell, Market, Kingshighway, Natural Bridge, and Jefferson were widened at this time in order to attempt to retrofit the streets for cars. This was all a product of the designs laid out by Bartholomew, which essentially laid the groundwork for making the automobile the center of how transportation worked in the city, as opposed to walking or streetcars, which had shared the street with carriages and automobiles up to that point. But as the automobile took over, it changed the way that streets worked, and Bartholomew was at the forefront of that change in St. Louis.

Through the 1930s and 1940s, the major focus in urban planning in St. Louis seems to have been the riverfront district, which was razed in 1940 to make way for a memorial, which later on became the Arch. Bartholomew had been involved in the planning for the project, and was an early proponent of using eminent domain to seize land to ensure that nothing would get in the way of the projects being planned. However, also during this time, the first clearances began around Union Station and City Hall, where the shops and businesses were demolished for parks and for the Soldiers Memorial, which was completed in 1937. While these were only small areas for clearance, they foreshadowed the much larger ambitions of Bartholomew that would come out at the end of the 1940s.

Nextstl – A Plan for the Central River Front – St. Louis, 1928

Nextstl – Plans for the Northern and Southern Riverfronts – St. Louis 1929

Nextstl – What “The Gateway Arch” by Tracy Campbell Tells Us About St. Louis

Following the Second World War, many American cities, including St. Louis began to look at redesigning their urban centers. This was commonly referred to as “Urban Renewal”, and its effects had major consequences for cities around the U. S. St. Louis was not immune from this, and Harland Bartholomew was at the forefront of the redesign. In 1947, he came out with the Comprehensive Plan for St. Louis, which ended up defining how the city would be laid out in years to come. No other document, except maybe those that separated the city and county in 1876, did more to damage the urban fabric of St. Louis.

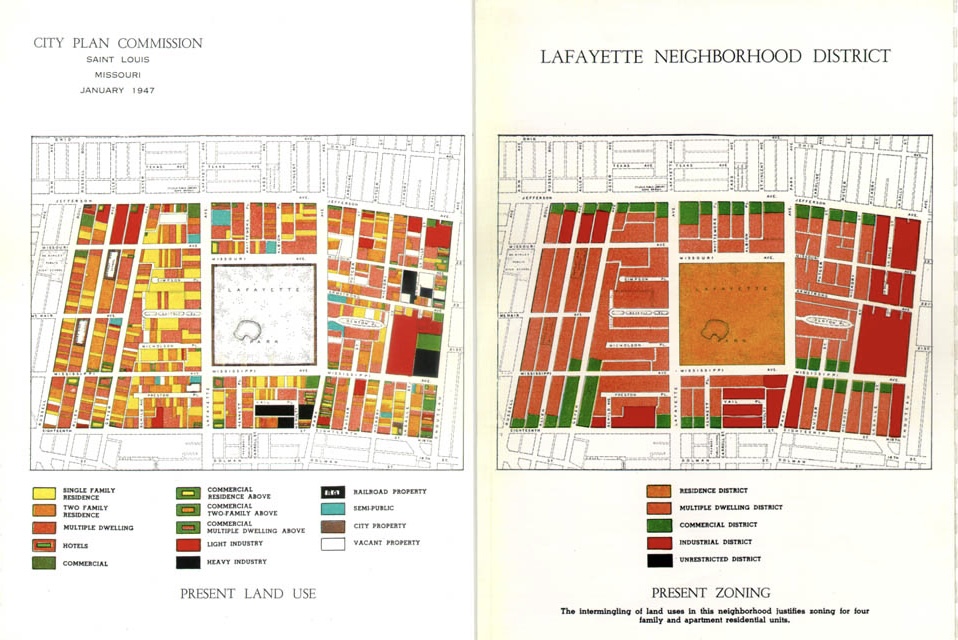

At the time of the 1947 plan, St. Louis was at its population peak of around 850,000 people. The goal of the plan seemed to be to ease congestion and to replace a lot of the city’s aging housing stock. One of the ways in which the plan set out in accomplishing this was through zoning. Rather than having mixed use urban neighborhoods, as was common in the 19th century, the Comprehensive Plan encouraged single use zoning in most areas. The idea was that the residential areas, commercial districts, and industrial areas would all be separated through zoning, and that each would be independent, rather than interspersed, as many parts of the city have been throughout their histories. It was also during this time that parking minimums were introduced, with one part of the proposal advocating for one parking spot for every four seats in a theater or assembly hall. The plan also shows many examples of how the city’s neighborhoods would be reorganized. The different residential areas were split into uses A through D, mostly following the population density and age of the housing, as well as the number of multi family units and boarding houses. Areas labeled as A or B were primarily single family homes, and were in the outlying areas at the edges of the city, while areas labeled as C or D were in the city’s urban core and had high population density housing, such as multi family buildings or boarding houses. Many of these areas were considered “blighted” or “obsolete”. Perhaps the most striking is the plan for the Lafayette Square neighborhood. The area, which had its most prosperous years in the 1870s-1890s, was no longer considered one of the city’s finest neighborhoods by 1947. The plan calls it an “obsolete area, for the most part.” It goes on to criticize the area as having an “incongruous inter mixture of all types of use”. The plan for the neighborhood at the time called for its demolition for the most part and reconstruction, except for some industrial and commercial uses along its main arteries. Today’s neighborhood is largely unrecognizable from this plan, or from its 1947 uses, but it has preserved numerous homes from its 19th century past.

Link to the full 1947 Comprehensive Plan:

https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/archive/1947-comprehensive-plan/index.shtml.

Another major part of the 1947 Comprehensive Plan was the rebuilding of what were considered the “blighted neighborhoods” of St. Louis. Bartholomew refers to these areas as having substandard living conditions, and being too overcrowded. Some of the common features of buildings considered substandard or obsolete include: cold water flats, which as the name denotes, only had cold water available, outhouses or privies, and a construction date before 1900. Bartholomew notes that the prevalence of these types of homes are “no way to build a sound city.” When looking at maps of the city from the plan, it is noted that much of the area east of Grand is either considered blighted or obsolete. The blighted areas were those considered to be declining and in need of rehabilitation, and in essence were considered neighborhoods that were going downhill, but would be salvageable with certain rehabilitation efforts and improvements. Neighborhoods like Benton Park, Shaw, O’Fallon Park, and others were grouped into this category. A common feature of the blighted neighborhoods was that homes in these areas were built between about 1880 and 1910, with relatively few structures from before 1880. Obsolete areas were often in the areas of the highest density, and the oldest parts of the city. An obsolete area was one that was considered to be too far gone to be saved, and in the plan, these areas were recommended for complete demolition and rebuilding from the ground up. Neighborhoods such as Soulard, Lafayette Square, Old North St. Louis, Mill Creek, and Carr Square were grouped into this category. A common theme with areas considered obsolete is that the buildings were built before 1880 for the most part, and the areas are filled with mixed use buildings that are interspersed throughout the neighborhood. Building age and urban density seem to have been deciding factors between blighted and obsolete neighborhoods, as can be seen with the difference between Soulard and McKinley Heights in the different categories, and the 50 year age difference between the two neighborhoods. Overall, the plan essentially called for the complete redesign of the innermost parts of the city, with most of the historic buildings having been replaced. In the plan, it was stated that “Present obsolete areas must be cleared and reconstructed. This is a social necessity and economic essential.” Also included in the plans were provisions that would have made the neighborhoods less dense and filled with more open space and more parks and playgrounds. These plans were meant to radically change the urban core neighborhoods of St. Louis.

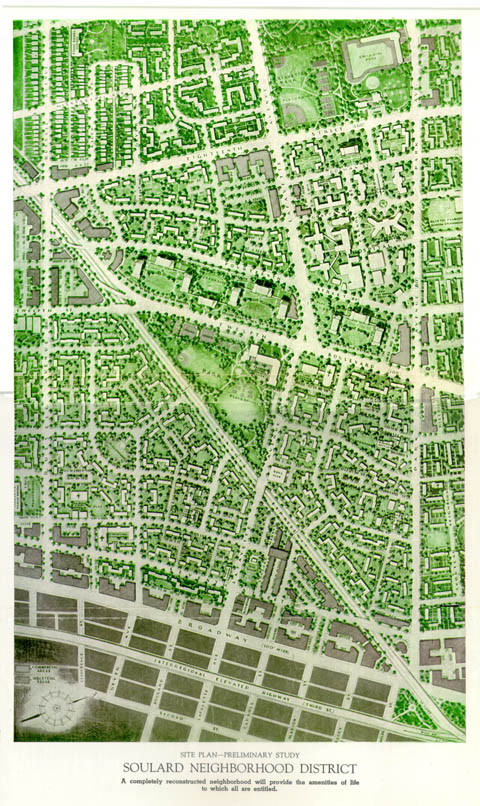

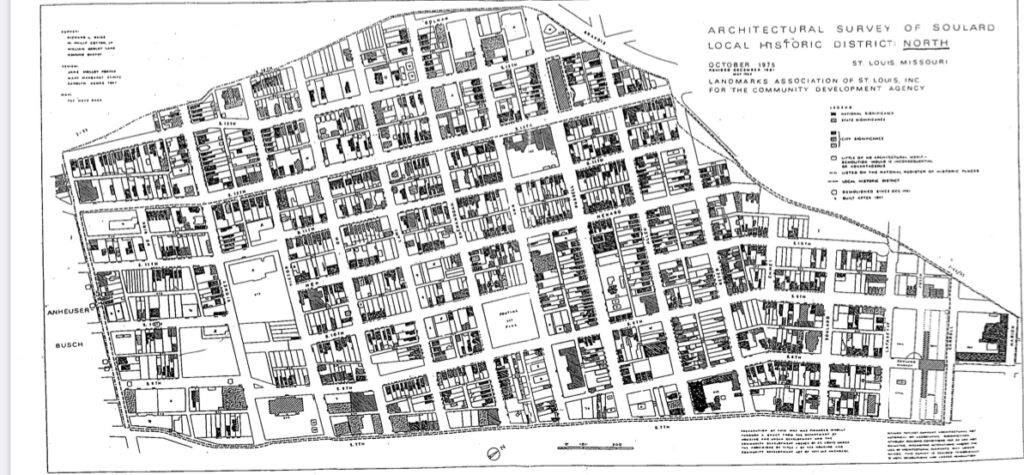

Not only did the plan call for the demolition and rebuilding of certain neighborhoods, but it also included plans for the final designs for what it thought some of the obsolete neighborhoods should look like. The two areas considered were the Soulard neighborhood and the Carr Square neighborhood. The radical approach of the Comprehensive Plan is perhaps best seen with the Soulard neighborhood, as the plan can easily be compared with the actual building footprints that existed in the 1970s, and are mostly unchanged today. The plan would have decimated the historic urban fabric of Soulard, and had plans to replace it with generic suburbia, such as what can be found in the mid century suburbs of St. Louis County.

Another major part of the Comprehensive Plan was the construction of highways and major thoroughfares. These plans built upon Bartholomew’s previous work widening St. Louis streets in prior decades. Streets were classified in four categories: secondary, primary 6 lane, primary 8 lane, and expressway. The 1947 plan was one of the first to propose major highways through the city, and it also encouraged a setback mandate to accommodate for the future widening of streets where needed. The actual highways that run through St. Louis are laid out a bit differently today than what the initial plans showed, but nonetheless, the plan had a major impact in the city’s planning during the mid 20th century

The aftermath of Bartholomew’s plans has been devastating to the city’s urban fabric. When one walks through the city today, they are greeted with walkable urban neighborhoods from the 19th century that are cut off from each other by wide roads that are inhospitable to pedestrian or bike traffic. Where the city once had well connected streets and seamless transitions between walkable neighborhoods, it is now a challenge for pedestrians to cross streets like Lindell, Gravois, Tucker, or Chouteau. The extreme width of these streets creates high speed sub-highways that are dangerous for pedestrians to cross. Another major damaging aspect is the concept of urban renewal, which was carried out in several neighborhoods. The most notable example of the clearance was seen with Mill Creek Valley, where 18,000 residents, primarily African Americans, were displaced by the near total destruction of their neighborhood. Not only was this neighborhood wiped out, but Carr Square was stripped of almost all its historic buildings as well, and had its population density reduced significantly. This was a direct result of the plans for the neighborhood devised in the Comprehensive Plan. Commercial districts in these neighborhoods were also destroyed, and communities were torn apart by the Comprehensive Plan and its long term effects. The city has still not fully recovered in some ways.

Despite the destruction caused by the Comprehensive Plan, many parts of St. Louis have survived and remain intact. Perhaps the best examples are Soulard and Lafayette Square. Despite being classified as obsolete, both neighborhoods experienced a major revitalization in the latter part of the 20th century. These neighborhoods have stood the test of time, and were successfully able to avoid much of the damage caused by urban renewal, except for the highways that cut through the neighborhoods. Their survival and success are real world examples showing that 19th century urban neighborhoods were much better examples of urban living than anything perpetuated by mid 20th century planners like Bartholomew or Robert Moses.

To add insult to injury, after creating destructive policies in the city of St. Louis, Bartholomew ultimately moved to Clayton. He died at the age of 100 in 1989, which was long enough for him to see the negative impacts that his urban planning had on St. Louis. To this day, Bartholomew and his legacy are among the most damaging to the city of St. Louis of anything that the city has encountered in its history.