Vacancy is difficult, and can be a controversial topic in St. Louis. Considering the array of federal programs coinciding the election of St. Louis’ next mayor, it is an important time to discuss our vacancy issues. We do not think we should worry about the open space of farmland or that Forest Park is empty. Yet unutilized vacant properties in urbanized areas can be of particular concern. Epitomizing disinvestment and dilapidation, they negatively impact neighborhood vitality and livability.

Why do they remain unoccupied and neglected? There are multi-layered and complex reasons contributing to urban vacancy, but simply put, the land is no longer attractive. It has been pushed out of the competition for space consumption, with suburban communities locally as well as with strong market metros nationally.

So the best solution to urban vacancy is to increase population and economic activity. But for many of St. Louis neighborhoods, this is a naive story. The most distressed vacant lots, which lack buildings or look derelict, are prominently clustered in North City, North County, and East St. Louis (the historical and socio-economic determinants, another contentious topic, of which are not dealt with here). It will be very challenging to increase population in North City and North County in the next decade when reflecting upon the recent trend of population dynamics.

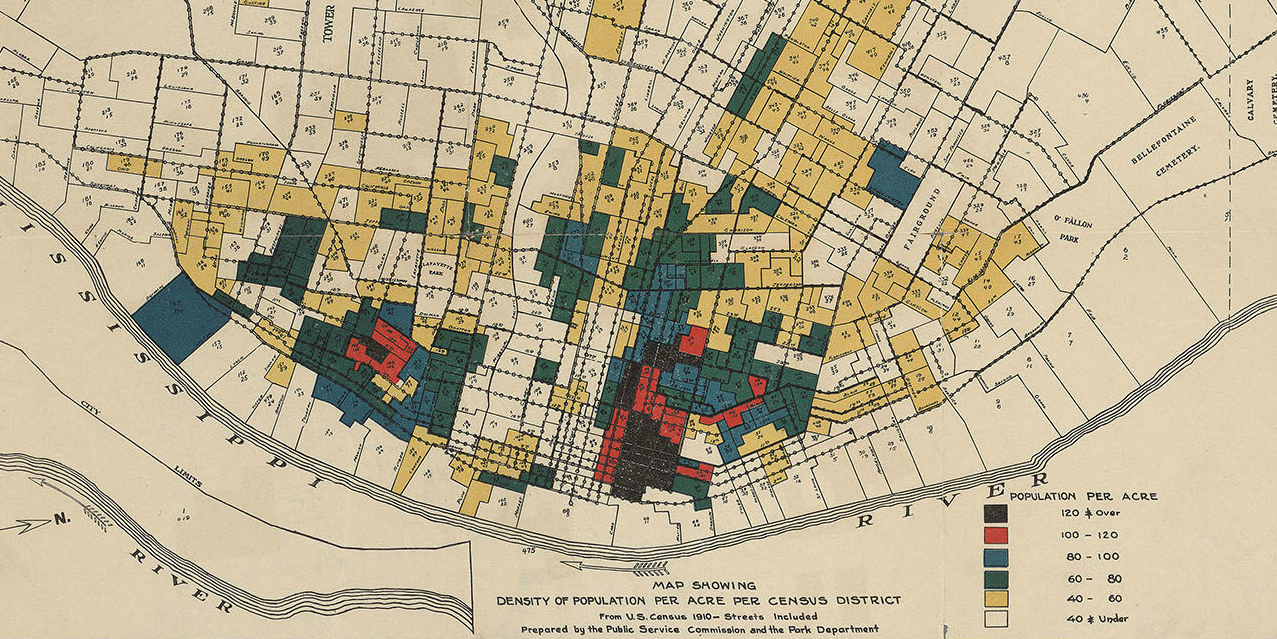

Though the population of Greater St. Louis has increased by 0.9% between 2010 and 2015, this is below the national average rate of 4.1% per U.S. Census Bureau estimates. More people have left than moved in. Natural increase, more births than deaths, has caused the slight population increase. Our region is not a popular destination for those who choose to migrate unlike thriving regions such as Texas cities where vacant sites in central cities are rejuvenated with infill projects.

Figure 1. Domestic Migration to and from the St. Louis Region, 1992-2011

Figure 1. Domestic Migration to and from the St. Louis Region, 1992-2011

If vacant land in North City is revitalized for housing purposes, the expected residents are likely relocated from somewhere within the region, not from other metros. Some initiatives appear to boost population and bring investment, but often to the detriment of other areas. We are facing a zero-sum game between municipalities and neighborhoods. The ideal scenario is to become a more prosperous metropolitan area in the longer run, but to accomplish this we must address the current realities.

Solving the vacancy problem equation relies on how vacant areas can become more inviting and regionally competitive communities. However, the city of St. Louis has an estimated 315,685 residents in 2015, a 1.2% drop since 2010; a similar trend can be observed in North County. One realistic approach acknowledging this tendency of depopulation is not to concentrate only on finding a permanent solution to surplus land. It demands a more holistic approach.

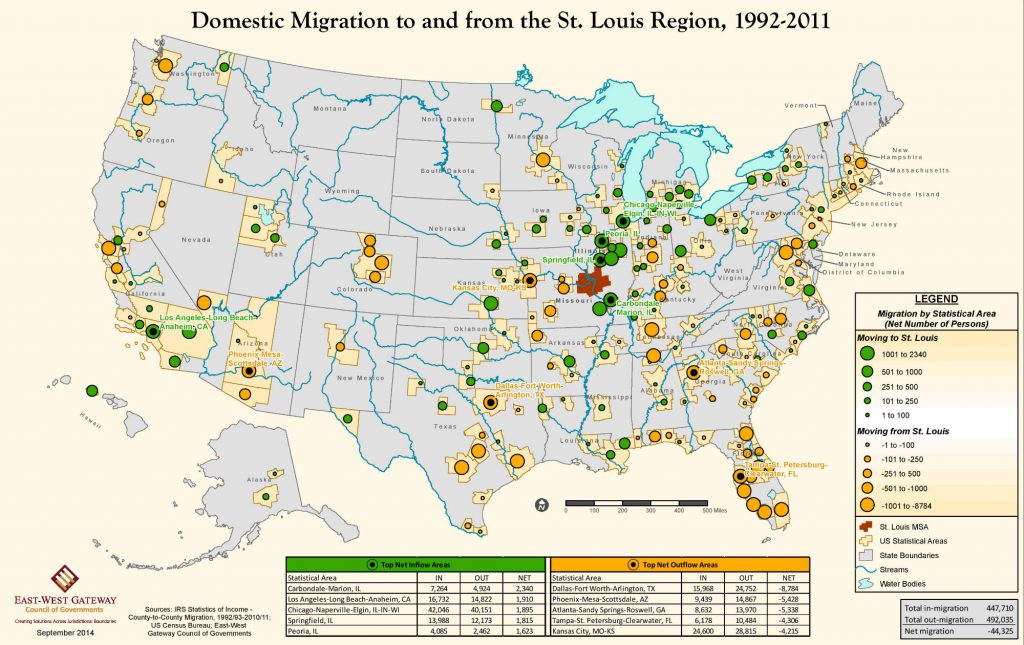

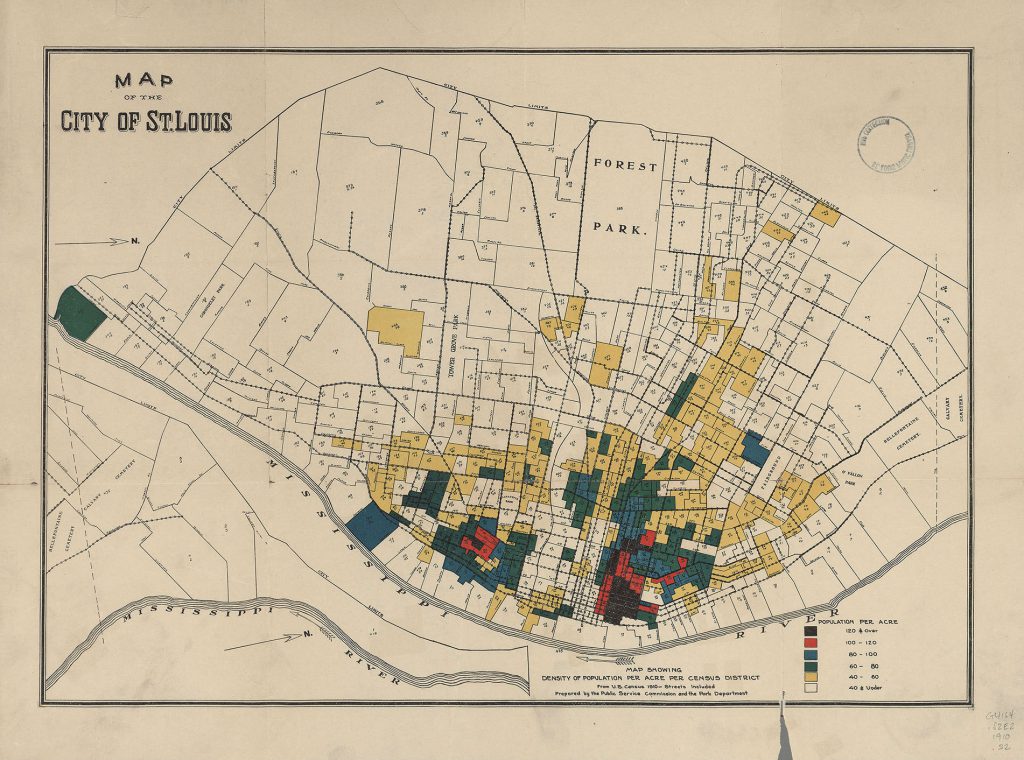

A clue can be found in the ward readjustment idea Prop R, passed 61.5% in November 2012, in which St. Louis City aldermen voted to reduce the city’s 28 wards to 14 effective January 2022 following the 2020 census result. It was back in 1809 that five trustees including the Chouteau brothers first initiated the Board of Aldermen, while the Charter of 1914 enacted the current city’s 28 wards with the population about 690,000, almost twice the current size. Maintaining half of existing wards is plausible and may be efficient, though the political and bureaucratic environment has changed. This map of population density in 1910 would help imagine how the city looked.

Figure 2. City of St. Louis Population Density in 1910

Figure 2. City of St. Louis Population Density in 1910

The problem lies in the city, which was originally designed for a 19th century system, and urbanized and developed in order to satisfy the demand of its heyday in 1940s, is not a perfect fit for today’s St. Louis. The region-wise inventory of vacant properties is probably larger than what we can use, even anticipating the maximum use of our resources combined with population growth in near future. The gap has steadily widened in previous decades, and we have either ignored it or could not manage it properly in a timely manner.

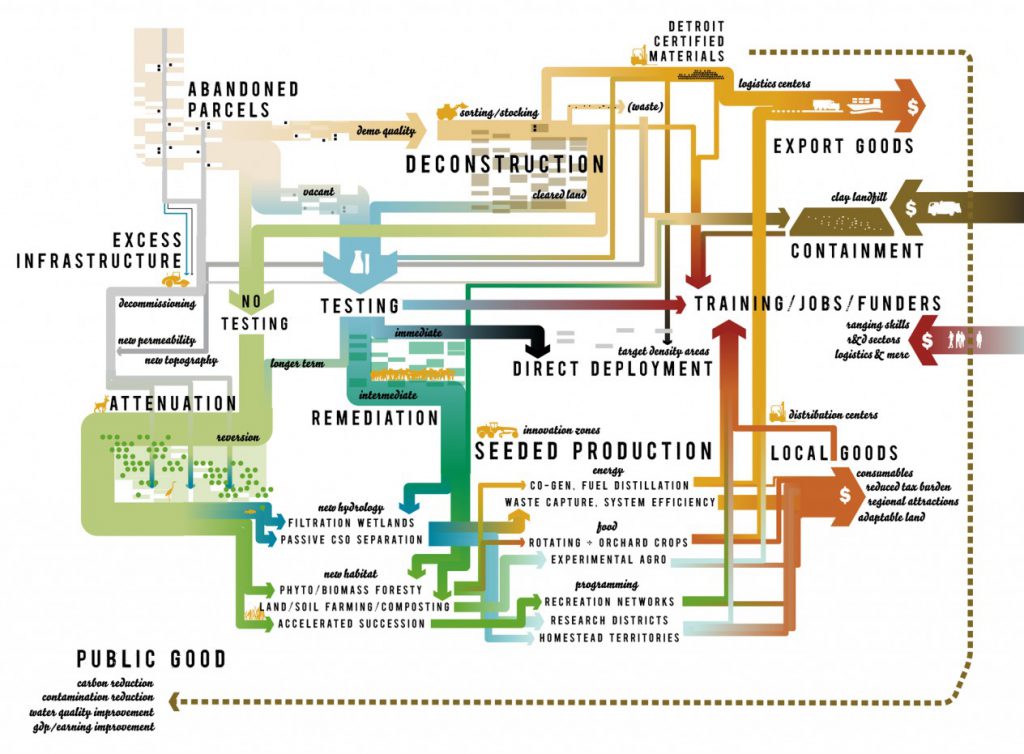

Assuming the gap began to grow in the 1950s and we are resilient, it could take a longer time to be restored. For example, the Detroit Future City transformation plan lays out a 50-year course of action. The long-term challenge of vacancy reduction requires commitment and focus on the future. We need a roadmap.

When Saint Louis University and Washington University in St. Louis graduate students were collaborating with Spanish Lake CDC in 2015 and Grace Hill last year, we looked for a guiding principle that can justify creative but implementable ideas ameliorating vacancy difficulties. Since the 1909 Plan of Chicago, the first regional master plan in this county, many plans have been created to envision a city’s destiny. St. Louis has a comparable one, Bartholomew’s 1947 Comprehensive Plan, but this is “the last formally adopted general plan” and becoming less and less relevant. The 26-page 2005 Strategic Land Use Plan is a classification approach assigning broad land use designations to each block, not a complete guide for decision-making or action plans.

Figure 3. Strategic plan conceptual framework, Detroit Future City

Figure 3. Strategic plan conceptual framework, Detroit Future City

St. Louis is a unique town. We should promote less locally-conventional approaches, but experimenting with non-localizable solutions from other cities needs to be reexamined. Creating a strategic plan reflecting our identity and values is essential as a process of engagement and a more socially just outcome. A recent publication of the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2017-2022 by St. Louis Economic Development Partnership is an example of such efforts while the focus is different.

We see a series of promising opportunities including Choice Neighborhood Implementation Grant, Promise Zone, SC2 (Strong Cities, Strong Communities) and the new NGA headquarters. The LRA (Land Reutilization Authority) is beginning to revamp its operation in acceptance of Center for Community Progress recommendations. These investments and transitions are conducive, but project-based and publicly driven initiatives are catalytic but not conclusive.

The city of St. Louis is going to elect a new mayor this year. We should challenge the candidates to a public debate to hear their vision and capability for the city’s future with respect to the vacancy issue. St. Louis did not get here overnight. Planning approaches will provide a way for benefitting our region and cities.

________________________________

This post is part of a collaboration between the Master of Science in Urban Planning and Development program at St. Louis University and nextSTL.com. The effort aims to utilize the planning talent and expertise within the program to highlight, address, and examine our city’s planning challenges. – Alex, editor