There are lots of “Most Dangerous Cities” lists published each year that rank inner cities with respect to crime. But only around twenty per cent of people in large metro areas live in the metro urban core on average. The other eighty per cent live in the suburbs. I decided to take on the task of aggregating crime data at the zip code level to compare metro urban core crime vs. suburban crime for the twenty largest metros in the U.S. And I was curious to see how crime correlated with average home values for large metro areas–one measure of the desirability of a place to live. The results are revealing.

Methodology

First, a short summary of the methodology: All of the analysis is based solely on metropolitan area-wide statistics or summed from zip code level data in the zip codes of the counties that comprise each metro area, and has no association with city limits at all. All the chart data was summed from three sources accessible by anyone with access to the internet, specifically, web sites tied to the National Association of Realtors, the US Census Bureau data, and the FBI crime tables.

The analysis uses the most recent data available from these sites as of May 2016. In this analysis, the urban core is defined as the inner twenty per cent, by population, of metro area zip codes closest to the City Hall of the metros’ primary core city. The suburban statistics are from the remaining outer eighty per cent zip code areas in the doughnut ring surrounding the urban cores of the metro areas, as defined by the Census Bureau using CBSA metro definitions. Details of the rest of the methodology are included at the end.

St. Louis and the Twenty Largest Metros

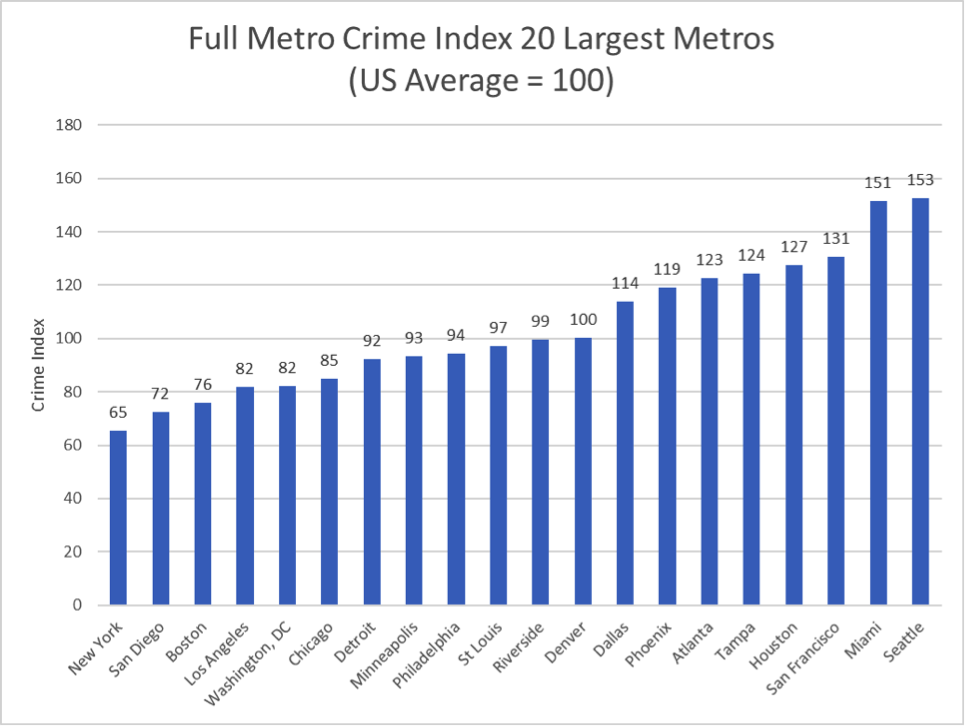

We start by computing a metro-wide crime index for each of the twenty largest metros from the same FBI metro crime categories used by the real estate web site [moving.com] for their zip code crime indexes. Figure 1 shows the result. St. Louis metro overall ranks a respectable tenth best for crime using this formula.

{Figure 1. Full Metro Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

{Figure 1. Full Metro Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

Adding a gold line to this chart for average home values and sorting from highest to lowest home values yields Figure 2 below. There appears to be little or no correlation between home values and crime indexes at the full metropolitan area level.

{Figure 2. Home Values vs. Full Metro Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

{Figure 2. Home Values vs. Full Metro Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

Many things can affect average home values, such as climate, transit options, schools, arts and entertainment, urban vibrancy, walkability, trails and outdoor recreation options, distance from the coasts, and crime. When it comes to crime, it is not easy to establish cause and effect. Are low home values a result of high crime, or are crime rates high due to low home values reflecting poverty?

Nevertheless, real estate websites feature crime statistics as a major factor for people to consider when deciding where to live. At the zip code level, we just assume that higher crime leads to lower home values. If any population group is able to reduce its crime rate, the real estate web sites will label it as more desirable and will steer home buyers to it, which should raise home demand and home values over time.

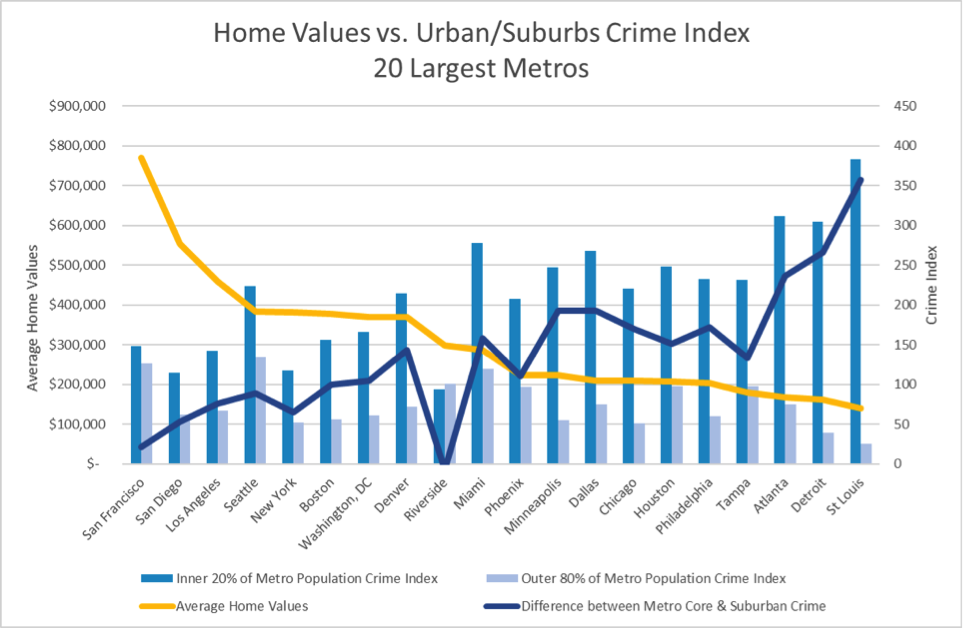

So if we believe that crime is one of the factors affecting home values at some level, we have to ask ourselves why St. Louis and other cities rank poorly in home values if their overall metro crime index is not bad. The Figure 3 plot below might have the answer. This plot is sorted by average metro home values again, but it splits metro crime indexes proportionately into two bars–core crime and suburban crime. The plot also shows the difference between core and suburban crime with the blue line.

{Figure 3. Home Values vs. Urban/Suburbs Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

{Figure 3. Home Values vs. Urban/Suburbs Crime Index—Twenty Largest Metros}

The results show that, along with the lowest home values of the largest twenty metros, St. Louis also has the worst urban core crime index, compared to the other metros. The chart shows a reasonable correlation between high urban crime and low metro-wide home values.

Figure 4 below is a map of the zip codes of the inner 20% urban core population and the outer 80% suburbs of the St. Louis metropolitan area.

{Figure 4. St. Louis Metro 80% Suburban and 20%Urban Core Zip Codes Maps}

{Figure 4. St. Louis Metro 80% Suburban and 20%Urban Core Zip Codes Maps}

St. Louis metro does rank well for low suburban crime. But suburban crime is low in most of the largest metros. And those low suburban crime indexes have not resulted in higher St. Louis home values. In fact, suburban crime indexes for all metro suburbs do not seem to correlate to higher home values in general.

Our low suburban crime could initially be seen by suburban residents as an argument against more regionalism over the fear that core crime could spread to the suburbs. But a closer look at the data shows that a large difference between urban core crime and suburban crime has an even higher correlation with low metro-wide home values–slightly more than urban crime index alone.

And St. Louis metro area ranks dead last in the difference between the crime index of its urban core and its surrounding suburbs of the twenty largest metros in the US. A clear inference from the data is that the gulf in crime between the inner core and the outer suburbs is the result of our region’s inability to apply resources, leadership, and crime fighting success of the suburbs to solve problems in our urban core. The result is the lowest home values of the twenty largest metros.

Pointer to a Path Forward

While there is nothing we can do to change our local climate or our distance from the coasts to improve home values, we can do something about urban vibrancy and crime. The data suggests that a cost effective way to raise all metro home values might be to enact a property tax on homes throughout the metro area and apply the funds to lowering crime only in the urban core. The data implies that the home property tax will be returned to the taxpayer many times over through higher home values. Of course creating better regional governance would make implementation of such a policy much more feasible.

Figure 5 below shows a plot of four large Midwestern cities and where St. Louis stands with respect to them for urban crime and metro home values. The plot indicates the level to which we could expect average home values to rise if we apply metro-wide resources to reduce urban core crime.

{Figure 5. A Path Forward for St. Louis?}

{Figure 5. A Path Forward for St. Louis?}

There are 1.2 million housing units in the St. Louis metro area [proxityone.com]. If St. Louis could move up just one slot in the home value ranking by reducing urban crime, up to Detroit’s level, it could add $21,300 to the average value of each home in the metro area, and add $26.3 billion for all home values combined. If we could move up to Minneapolis’s numbers over the next twelve years, it could mean an average increase in home values of a whopping $82,100 average per house in the entire metro area, and add over one hundred billion dollars to our metro home value base.

We could use the current numbers of these Midwestern metros as intermediate goals for St. Louis over the next twelve years to help us decide how much metro money to devote to reducing core crime. Then, if our metro creates a regional plan to directly address our urban crime, we can measure our core crime reductions and home value increases against these metros to see if our plan is on track.

A Proposal

How much is enough money to devote to core crime reduction to raise metro home values? If core crime was the sole driver to metro home values, you might say spending $80,000 per house in the metro area is not too much to spend if we were guaranteed the Minneapolis numbers. But since urban crime is only a significant factor—not the only factor—and since we can probably get huge reductions in crime for far less than that number, we should not have to go to that extreme.

Another way to look at this is to ask: what level of spending on community policing and training, improved education, more jobs and job training, drug treatment, and new public community facilities would finally break the back of crime in the metro urban core—the inner twenty per cent of our metro area on both sides of the river?

A part of the equation will involve breaking the psychology of using guns to resolve conflicts among individuals. Treating gun violence as a community health issue and establishing community centers could allow us to break that psychological cycle of violence. Also generating jobs for the unemployed in the urban core is crucial, and could be publicly funded if we include skills training that can be applied anywhere in the metro area. What better way to gain construction skills, for instance, than learning to rehab houses within the urban core?

I’ll leave it up to trained urban planning experts to generate a viable detailed plan for reducing urban crime. But for now, consider this approach to a twelve-year plan to reduce core crime and raise home values metro-wide. While police budgets in the urban core cities are currently around one and a half times the budgets of suburban towns per person, the crime challenge at the core of our region is at least four times as great per person for a variety of historical reasons.

Adding $60,000,000 per year total to police budgets in the core cities of the St. Louis region should give an expanded police force time to engage in additional community policing at the street level. Next, we should consider creating ten thousand jobs at $30,000 per year working infrastructure and rehabbing abandoned homes in the region at a cost $300,000,000 per year. And adding new facilities for training, treatment, and community centers could cost another $40,000,000 per year.

Total cost would be $400 million per year for twelve years. Dividing by the 1,236,676 houses in the metro area would add $323 dollars per house per year to average home property taxes, or about 23 cents per $100 valuation per year for twelve years for the current average metro home value of $140,700. After twelve years, the metro could decide to reduce the funding, or divert some of it to another goal such as core school improvement. Or, if home values start rising as urban crime is reduced, the tax rate could be lowered and still generate the same level of funds.

If we believe that spending $400 million per year for twelve years would lower the inner core crime down to the Minneapolis levels, and home values would rise to Minneapolis levels as a result, then we could expect to get an average home value rise of $82,100 dollars per house for a home property tax investment of only $3,876 per home on average. ($323 times 12 years) for a total return on investment of over twenty to one. But if it is only two to one, it will have been worth it.

Conclusion

I believe the data show that it pays financially for the greater region to invest in solving the metro’s core problems if all portions of the region chip in, including St. Charles County, Jefferson County, and all other metro area counties in Missouri and Illinois. And the payoff might be huge for homeowners throughout the greater regional area. We could give the effort an identifiable name to help rally support, such as St. Louis MACS–Metro Advancement through Core Security.

It would be funded with a twenty-three cents per hundred-dollar valuation property tax on all homes in the metro counties on average, and it could include a sunset clause to end the program after twelve years. St. Louis MACS could be roughly patterned after the successful MAPS program that Oklahoma City executed in the late 1990s and 2000s to restore their city center. MAPS was so well managed and so successful that voters renewed the MAPS tax to address schools after the city core was booming again. St. Louis could do the same.

________________________________

Methodology Continued

I began by compiling crime index data down at the zip code level, using publicly available data from Total Crime Risk values found on the real estate web site moving.com, part of the National Association of Realtors. The site displays a crime index for each zip code computed from a sum of seven of the eight FBI counts of murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny theft, and motor vehicle theft, (leaving out property crime.)

The sum is converted to a crime index by comparing it to the national average pegged to an index of one hundred. A zip code crime index of two hundred, for example, represents double the US crime risk. This formula is identical to the one the FBI included in crime tables before 2004, the last year they included a crime index. While we may not be happy with this crime index formulation, it is the one being used by prominent real estate sites to help people decide where to live.

To find which zip codes comprised the inner twenty per cent of the population of each metro area, I started with U.S. Census Bureau tables that listed all zip codes for each metro area, the population of each of those zip codes, and the latitude and longitude of those zip code areas. With this data, I could determine the zip codes in the inner twenty per cent, by population, of each metro area.

Once I determined the zip code areas for the inner twenty per cent urban core, I retrieved the crime indexes for those zip code areas and used them to computed a single crime index for the urban cores, weighting individual zip code indexes by their population so a zip code with only three people would contribute proportionally less than one with three thousand people.

Then I could compute the crime index for the outer eighty per cent of each metro area as the number that, when combined proportionally with the inner twenty per cent number, yielded the full metro crime index composed of the same crime category counts from FBI Table 6. Full metro average home values came from realtor.com, owned by the National Association of Realtors.

________________________________

This post first appear on the St. Louis Strong site. The post was featured in Tony Messenger’s column for the Post-Dispatch. At nextSTL Gary has contributed A Better Alternative to “Most Dangerous Cities” Ranking and Don’t forget Napoleon at the Gateway Arch.

________________________________

At nextSTL we have written extensively about crime and statistics:

The St. Louis Metropolitan Region: Safer than Santa Fe (and 101 other MSAs)

From the Nation’s “Most Dangerous” City: St. Louisans Say they Feel Safe Walking Alone at Night

Understanding St. Louis: Homicide and Index Crime Totals and Rates 1943-2012

Understanding St. Louis: Total Crime Index, Violent Crimes and Property Crimes in City Neighborhoods

Understanding St. Louis: Total Crime Index and Crime-Ridden Neighborhoods