There are at least two distinct lines of thought regarding economic development incentives in the City of St. Louis. One believes that incentives are absolutely necessary to generate investment, that “but for” the incentives, development would not happen. The other believes that incentives are a giveaway to big developers and real estate interests that impoverish the city and particularly burden residents outside the incentive system.

There are at least two distinct lines of thought regarding economic development incentives in the City of St. Louis. One believes that incentives are absolutely necessary to generate investment, that “but for” the incentives, development would not happen. The other believes that incentives are a giveaway to big developers and real estate interests that impoverish the city and particularly burden residents outside the incentive system.

The comprehensive City Economic Development Incentive report commissioned by the St. Louis Development Corporation and executed by the PFM Group, will satisfy neither camp. The report recognizes that due to the complexity of economic and political factors involved, no definitive conclusion as to the impact or necessity of incentives is possible. The report has not been released by the SLDC or City of St. Louis, but was obtained by nextSTL.

The short of the 198-page report? St. Louis City is doing what most large cities do. The process for applying and being approved for incentives is formalized. However, the city’s fragmented governance is confusing and lacks transparency. While much of the incentive activity is analogous to other similar cities, the notable outlier in St. Louis is the degree to which each of the city’s 28 aldermen “can heavily influence the process”, particularly with tax abatement.

[Read the full St. Louis City Economic Incentives Report]

Economic incentives are offered to further city goals of economic development. Those goals, by industry, or geography, or other measures, are not clear in St. Louis. This report offers a clear look at the cost of incentives, and approaches different ways to consider benefits. Yet, it’s not possible to determine if incentives achieve any goal of the city beyond the amorphous and simple ledger of “economic development activity”, because the city lacks such determined goals.

Also, as the study notes, the city lacks a process to effectively track incentives and evaluate their impact. There are positive outcomes for specific development sites, while the catalytic effect is likely overstated. One simple finding of the report is that from 2000 t0 2014, the total value Tax Increment Financing (TIF) incentives in the city totaled $401.6M. The value of property tax abatement over that same period was found to be $307.5M.

These numbers provide a perfect example of why the various incentives require context. The tax abatement total of about $20M a year covers all taxing jurisdictions. A very quick estimate shows that this equates to approximately $4M for the City of St. Louis, or about 1% of its true operating budget. For the St. Louis Public Schools, the number is near $12M, or 3% of its budget. The total value of the average tax abatement on a single-family home is about $11K.

The report does make suggestions, stating they are offered as “best practices” and any implementation need consider local policy, political, economic, social or other considerations. That seems smart, or at least pragmatic, if not satisfying.

The report set out to answer the following four questions:

1. What is the dollar amount of incentive use?

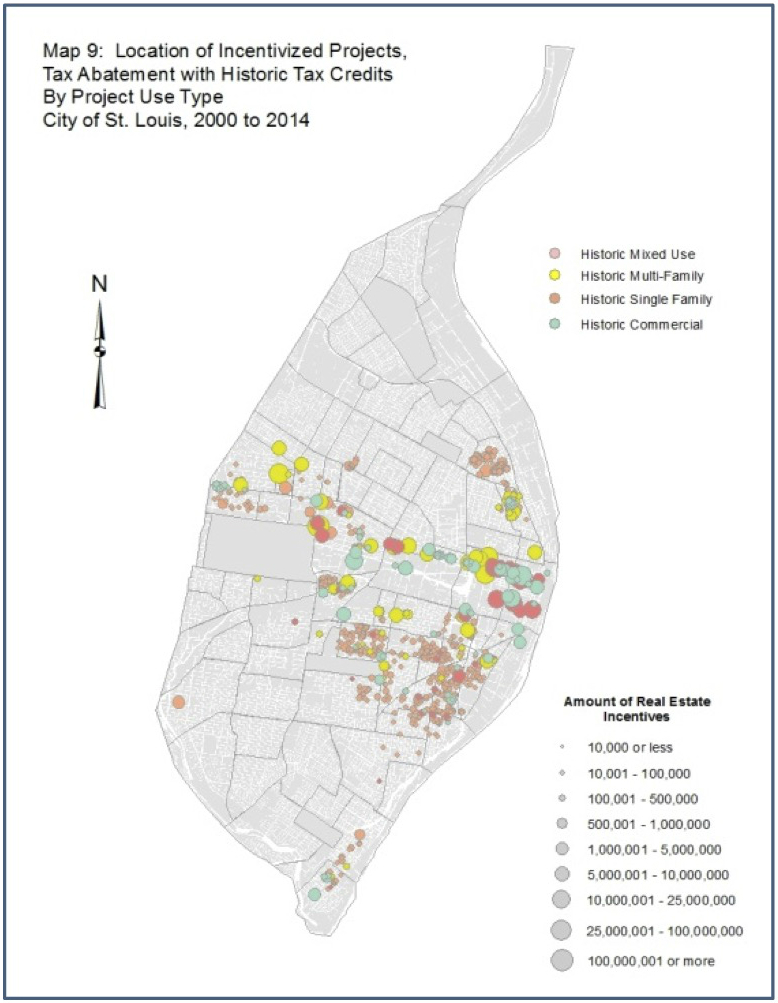

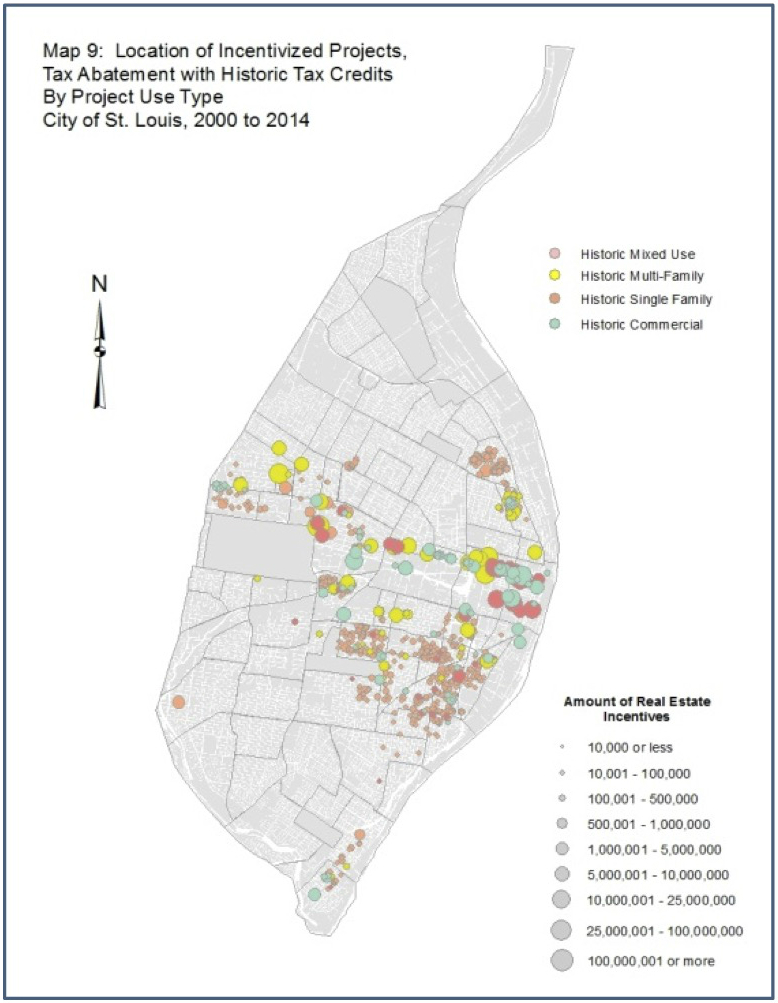

2. Where and when have incentives been used in the City?

3. What are the characteristics of incentivized projects in terms of either available data on incentives or the available data on the projects?

4. How were incentives layered to complete projects, particularly where local incentives were used

alone and where local incentives were combined, with state level or other incentives?

The report’s five recommendations:

1. Establish a formal framework for reporting and analyzing the incentives data contained

within this report.

2. Build greater quantitative measures into the application scoring process for incentives.

3. Require additional reporting from incentive recipients.

4. Focus incentive use around a City-wide plan for development.

5. Develop a formal tax incentive related to creating high skills/high wage and benefits jobs.

There are so many caveats, so much necessary context, in a study like this that it is truly necessary to read the study to understand it. There are tables of numbers that are tempting to see as definitive or conclusive, but require 500 words to explain.

The primary focus of the report is stated as: Tax Increment Financing (TIF), Real Estate Tax Abatements, Chapter 100 Sales Tax Exemption for Eligible Personal Property, New Markets Tax Credits, Enhanced Enterprise Zone, and Tax Exempt Bonds. National benchmark cities include Baltimore, Detroit, Kansas City, Louisville, Memphis and others, while the report also examined the use of incentives locally in Brentwood, Chesterfield, Clayton, Kirkwood, Maryland Heights, and University City.

Of particular interest are two of eleven listed tax incentive programs, real estate tax abatement and tax increment financing. What follows are excerpts and adaptations from the report, something of a select editorial summary. Again, the report deserves to be read in its entirety.

Real Estate Tax Abatement: A City incentive program for commercial, industrial or residential

uses that assists individuals, developers and businesses with renovation and new construction

projects. It provides that the real estate assessment on improvements will be based on the predevelopment value, with a usual term of full abatement for 5 or 10 years. The state statute

authorizes the City to provide up to 25 years of abatement (10 years at 100 percent abatement, plus 15 years at 50 percent abatement).

Tax Increment Financing (TIF): A City program designed to help finance certain eligible improvements to property using the new tax revenue generated by the project after its completion. This new tax revenue includes increased assessment on real property as well as 50 percent of any new local economic activity taxes (such as sales taxes, earnings taxes, utility taxes) while the TIF is in effect. TIF can be authorized for a term of up to 23 years. The report includes a nice history of TIF (come to be in California in 1952).

Tax Increment Financing (TIF): A City program designed to help finance certain eligible improvements to property using the new tax revenue generated by the project after its completion. This new tax revenue includes increased assessment on real property as well as 50 percent of any new local economic activity taxes (such as sales taxes, earnings taxes, utility taxes) while the TIF is in effect. TIF can be authorized for a term of up to 23 years. The report includes a nice history of TIF (come to be in California in 1952).

These two incentives are combined and separated from the other incentives because they represent some level of foregone City revenue. In the case of TIF and abatement, there is a real possibility that the City is accepting a reduction in its tax revenue in return for new economic activity. It could be argued that some (perhaps most) of this forgone revenue would not have materialized without the incentive (which is commonly referred to as the cbut ford test a the project would not have occurred and the economic activity that results in the additional tax revenue would also not exist but for the incentive), but it is also likely that some tax revenue is being lost by the City as a result of these incentives.

While TIF and abatement may be considered foregone revenue (subject to the discussion in the preceding paragraph), this is not the case for state and federal tax credits and local bonds. In the case of the federal New Markets Tax Credits (which is an oft-used incentive program), the benefit is a credit against federal taxes and has no impact on City revenue. In the case of local bonds (which have totaled $2,912.90 million), the St. Louis Development Corporation and/or the Industrial Development Authority act as a conduit issuer of the bonds on behalf of the benefitted corporation or public entity, which his responsible for their repayment.

The tax benefit flows from the federal and state government to those who purchase the bonds in the form of the interest paid on the bonds being exempt from federal and state income taxes. There is no real impact on the City budget from issuing these bonds, and they should not be characterized as a tax incentive in the same discussion with TIF and property tax abatement. It should also be noted that during this same time period, St. Louis projects have received approximately $2.03 billion in state incentives. Again, while important for economic and community development, these state incentives in no way reduce City revenue.

Overview of TIF Utilization: After years of population decline and economic transition, St. Louis is now seeing new growth in its central neighborhoods. From 2000 to 2010, the number of college-educated young adults living within three miles of the urban core increased by 138%. Not only was this growth rate faster than at any time in the past half-century, but it was also the fastest among all U.S. metro areas with over 1 million residents.

Despite this, St. Louis continues to have an abundance of older vacant properties. In an effort to remedy this, St. Louis has made heavy use of TIF to redevelop neglected and abandoned properties, mostly within, or close to, the downtown center. Similar to findings in the 2009 report, the City has continued to show success in redeveloping properties into profitable developments, particularly those centered on its downtown area and adjacent neighborhoods. Along with TIF, state development incentives, including the Missouri rehabilitation tax credit for historic properties, continue to be accessed for economic development projects within the City.

Tax Abatement: The following requirements must be met for a project to be eligible: Properties must be new construction or extremely deteriorated requiring extensive rehabilitation. The Alderman of the ward in which the property is located must support the project (so that legislation can be introduced to authorize it). An application for small property tax abatement must be submitted for each property requesting tax abatement.

Tax Abatement Evaluation: The City’s tax abatement policies are generally expansive enough to allow for a variety of eligible developments. Somewhat unique to St. Louis, because tax abatement is authorized by ordinance, tax abatement approval is dependent on the support of the Alderman of the ward where the development is located; the Alderman may apply special conditions as a condition of support. In many similar cities, tax abatement criteria for eligible projects are specifically defined, and City Council involvement is limited to end review and approval of projects.

St. Louis’ significant reliance on Alderman involvement in the process is outside of the norm; it is notable that the City allows abatements for any Board of Aldermen-approved property. Similar to its TIF guidelines, St. Louis’ tax abatement policies allow for abatements on the added value from property improvements. Some peer cities abate a fixed percentage of total property tax liability or adjust the abatement in line with the fulfillment of job creation and new investment criteria.

Impact of Incentive Use: There is a strong association between incentive use and increased assessed value and aggregate permit investment from 2000 to 2014. This is probably because incentive use follows overall investment patterns. Conversely, there is little relationship between incentive use and an increase in jobs within neighborhoods.

Much of the benefit to neighborhoods from incentive use comes from increased assessed values of the parcels that receive the incentive and other investments. For example, assessed values rise significantly for incentivized parcels for both parcels that receive TIF and parcels that receive TA, particularly when those local incentives are matched by state real estate incentives.

On the other hand, there is little evidence of significance spillover effects around incentivized parcels after the use of incentives. Across most project types, there is no significant change in the trajectory of assessed value, permit investments or jobs.

This suggests that city development officials should be careful about ascribing local or neighborhood effects to a specific incentivized project. While there might be cases where incentivized projects are transformative for local communities, it is probably the sustained, consistent use of both incentives and overall investment over time, including investments of a variety of types, which increases local economic outcomes and transforms local communities.

One good example of raw information presented requiring significant context is the geographic distribution of particular incentives. Using an accounting ledger, Downtown received 47% of all incentives examined, Downtown West-11%, and the Central West End-7%.

As the study offers, there is a “BIG caveat”: Given that much of this incentive use requires investments by private developers, it should be understood that these neighborhood totals reflect the choices of developers to invest in particular types of projects in particular markets. These projects include: The use of historic tax credits, TIF financing and tax abatement to redevelop lofts downtown, The use of historic tax credits and tax abatement to redevelop property in historic districts in the City.

The use of low income tax credits, tax abatement and other incentives both state and local to construct affordable housing in some north and south St. Louis neighborhoods. Additionally, because Downtown has been an area of significant developer activity over the last 15 years, it is logical to expect that it has been the location of a significant amount of incentives. For example, Downtown, which had $2.8 billion in total and $1.1 billion in real estate related state and local incentives from 2000 to 2014, had over $9.7 billion in total permit activity in the same period.

A project team conclusion from analysis of the data is that areas with higher overall investment are likely to see greater use of incentives, and the raw dollar amounts of incentive might not tell the whole story regarding their distribution in the City.

Assessed value: Neighborhoods with large increases in assessed values over the period also saw the largest aggregate permit investments Over the analyzed time period, assessed value increases approximately $143 million per year. By contrast, permit investments decrease approximately $167 million and the number of jobs decreased by 430 jobs per year. Additionally, there is year-to-year variability in the data. For example, assessed value increases in the years up to 2008 and declines marginally after that. Permit investment peaks between 2002 and 2005 and falls to a stable annual pattern afterward. Jobs in the City peaks in 2004, falls through 2009 and rises by 2013 to match the number in 2002. One interesting note to each of the time trends maps is that increases in assessed value are generally quite moderate after the initial increase after TIF use.

Summary of Impacts: In summary, the trend analysis seems to concur with the initial analysis that, while incentives are associated with positive economic benefits at the neighborhood level, these impacts are restricted largely to the parcels and project areas in which the incentive occurs. On average, there is little evidence of clear spillover effect from the use of incentives across most of the projects for most of the economic impacts. Impacts at the level of parcel or project area are most clear for assessed value—indeed, this impact is relatively long lasting, meaning that the city could potentially continue to recoup the benefits of the incentive use after the incentive period ends— which is often 10 years for tax abatement and much longer for TIFs.

For incentive supporters, a city that chooses not to provide incentives while their competitors do is engaging in a form of unilateral disarmament that could have significant negative consequences. Supporters can also generally point to specific instances where incentives have helped obtain or retain a business – or improve the economic condition of a neighborhood or area of a city.

This study was not focused on determining the ‘correct answer’ to this policy dispute. Further, to some extent this is an academic discussion. While the debate on whether or not tax incentive are effective rages on, in practice, local governments continue to offer them, and there is little evidence that this is changing or will change in the near future. Where both sides would likely agree is that incentive policy should be structured to obtain as much public benefit as possible and provide as much data for research and analysis on this public benefit as well.

In 2011, the East-West Gateway Council of Governments published a study on the fiscal impacts of the use of development incentives in the St. Louis Region. It indicated that the incentives had not had a general beneficial economic impact on the region. Among its specific findings: The use of TIF and other tax incentives, while positive for the incentive-using municipality, has negative impacts on neighboring municipalities.

While the East-West Gateway report makes a reasonable case for its findings and conclusions, it is far from a compelling indictment of all uses of economic development incentives. Indeed, the report notes that there are effective uses of incentives; in fact, it highlights effective use of incentives by the City of St. Louis but argues that economic benefit in this case comes at the expense of other communities within the region. This is worth discussion as a regional issue, but it does not provide a compelling indictment of the City use of these incentives: a case can be made that the surrounding communities have certain advantages in competition for jobs and residents that at least balance out these negative impacts. Indeed, one earlier study of the use of TIF in Kansas City and St. Louis concluded that use in the St. Louis region should be shifted more to the inner core (City of St. Louis) and away from outer cities.

Economic Development Planning: As previously noted, in most cities, economic development incentives are considered to be a tool to be used to advance the overall development plan, and city departments with development responsibilities work with those responsible for planning to implement that approach.

The St. Louis approach of involving the Alderman for the particular ward where the development would occur is not necessarily an impediment to that approach, but it involves the legislature at a much earlier point in the process than is normally the case.

It may well be the case that it would not be politically feasible or practical to dramatically end this involvement. It may well be that this involvement also provides opportunities for more neighborhood and ward engagement around development. To reflect that fact, an alternative would be to build on a zone- based approach toward eligibility for certain economic development incentive programs.