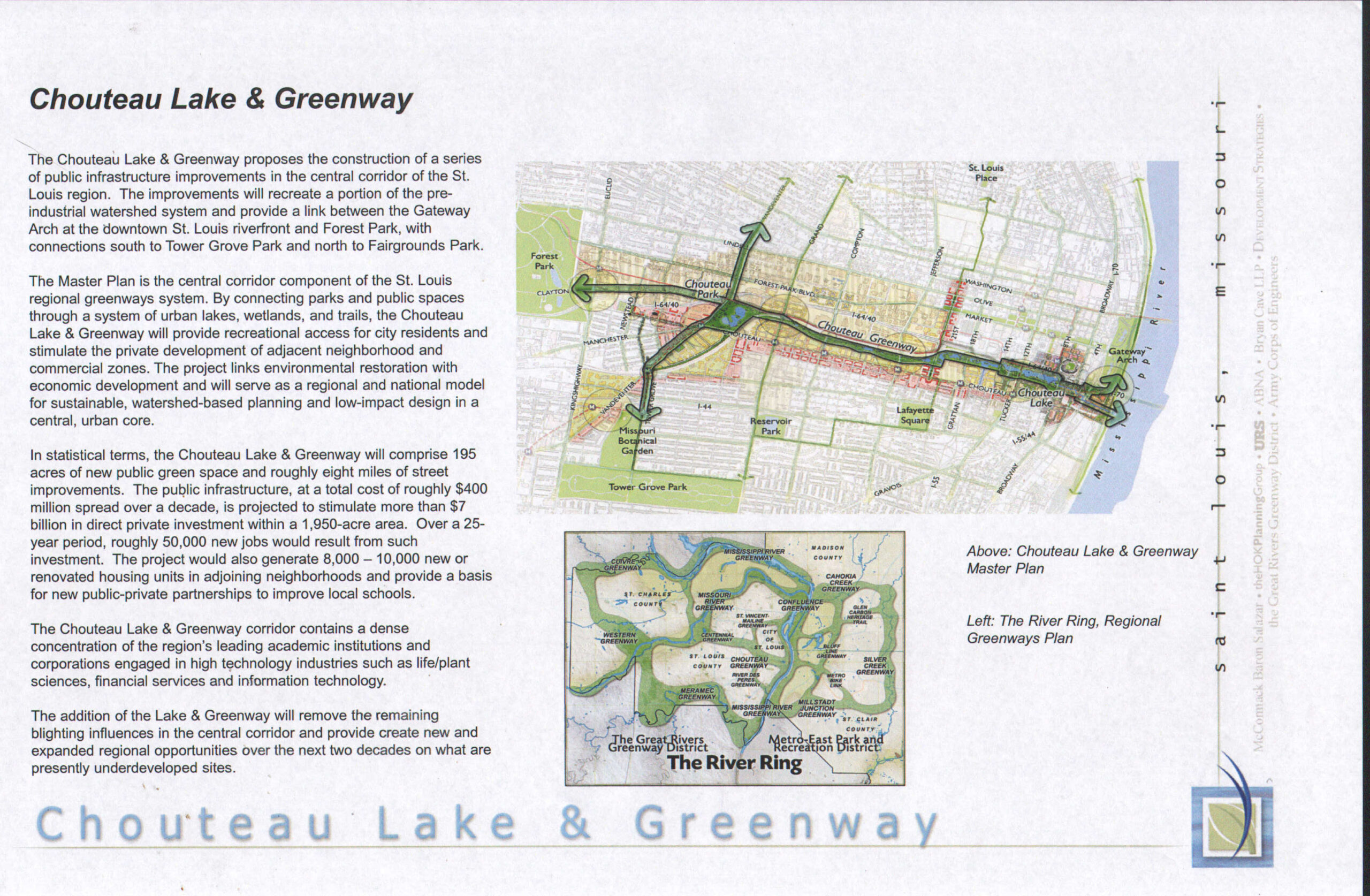

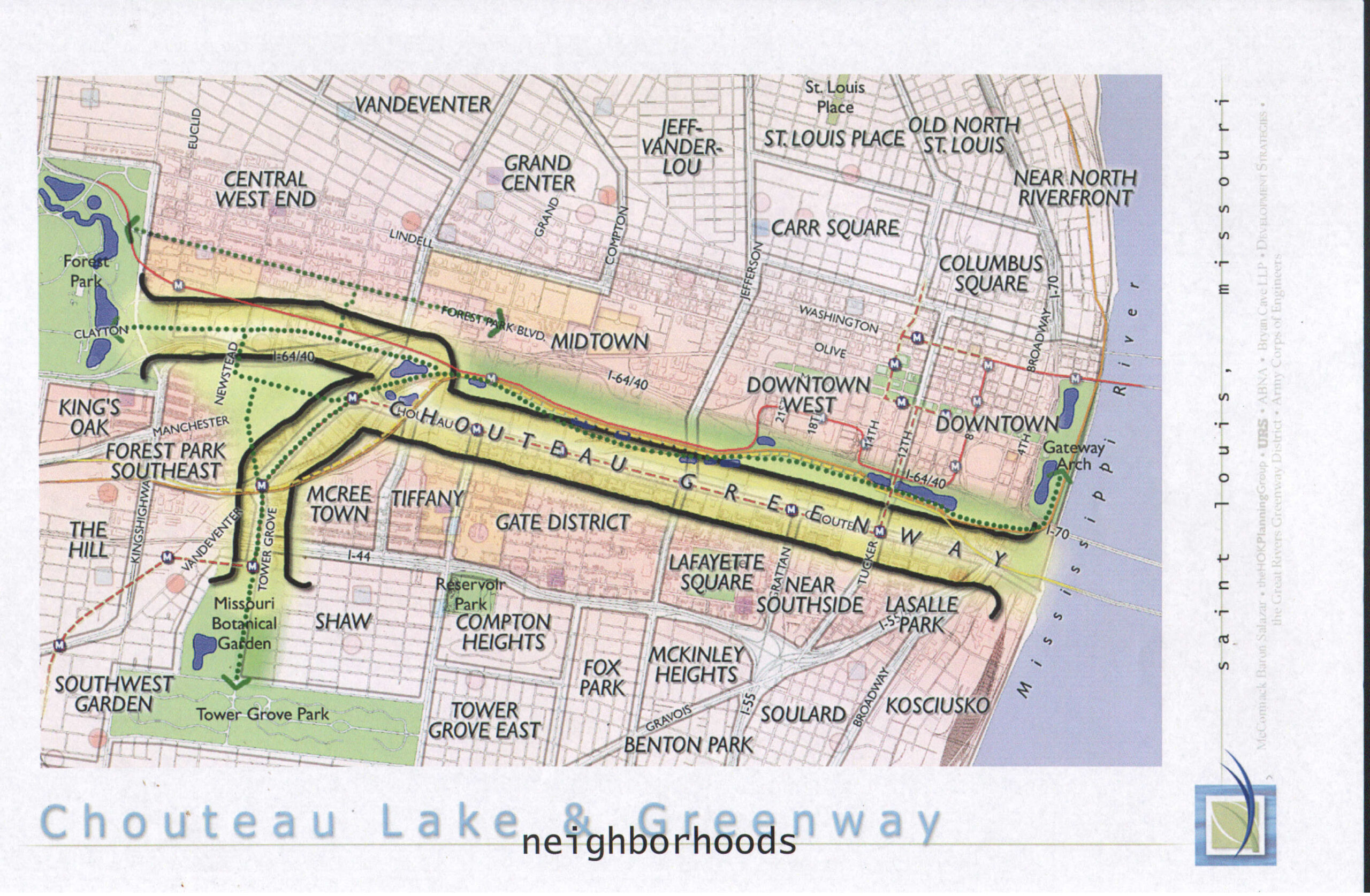

Recently, NextSTL ran Revisiting the Chouteau Lake and Greenway Plan and Imagining a Traffic Free Corridor. In that article, I discussed the plan’s merits, questions involving its demise, and its continued prospects for transforming the Mill Creek rail valley.

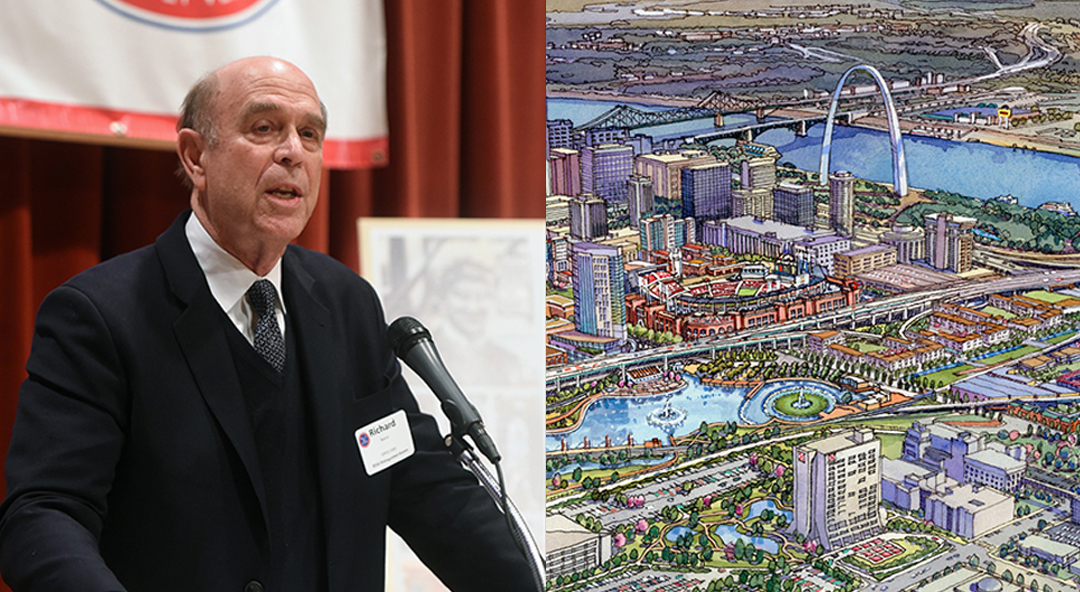

The plan’s creator, developer Richard Baron, Co-founder and Chairman of McCormack Baron Salazar, reached out and offered to speak with me about the history of the plan.

Here are the highlights of that conversation:

On the plan’s origins

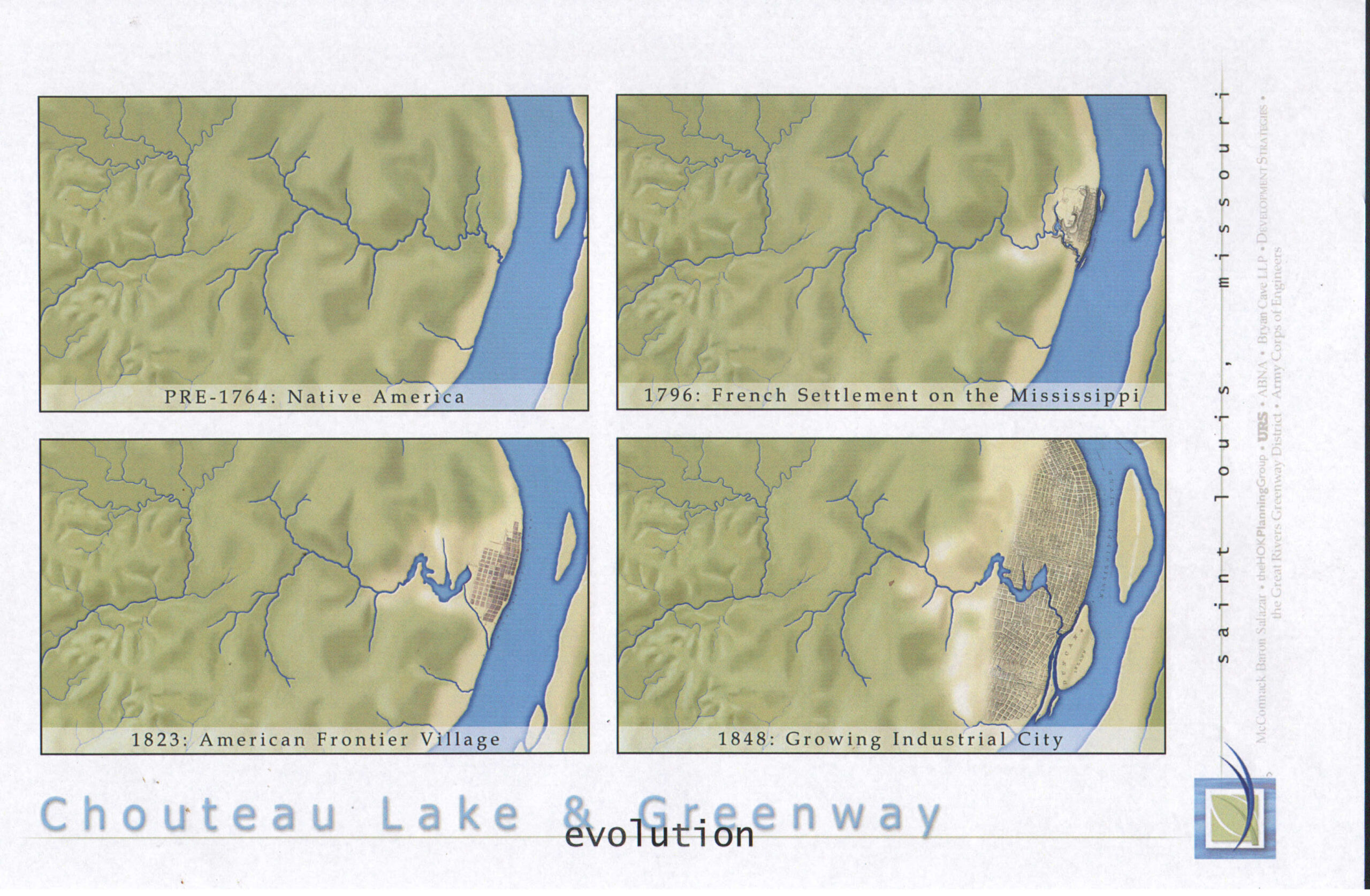

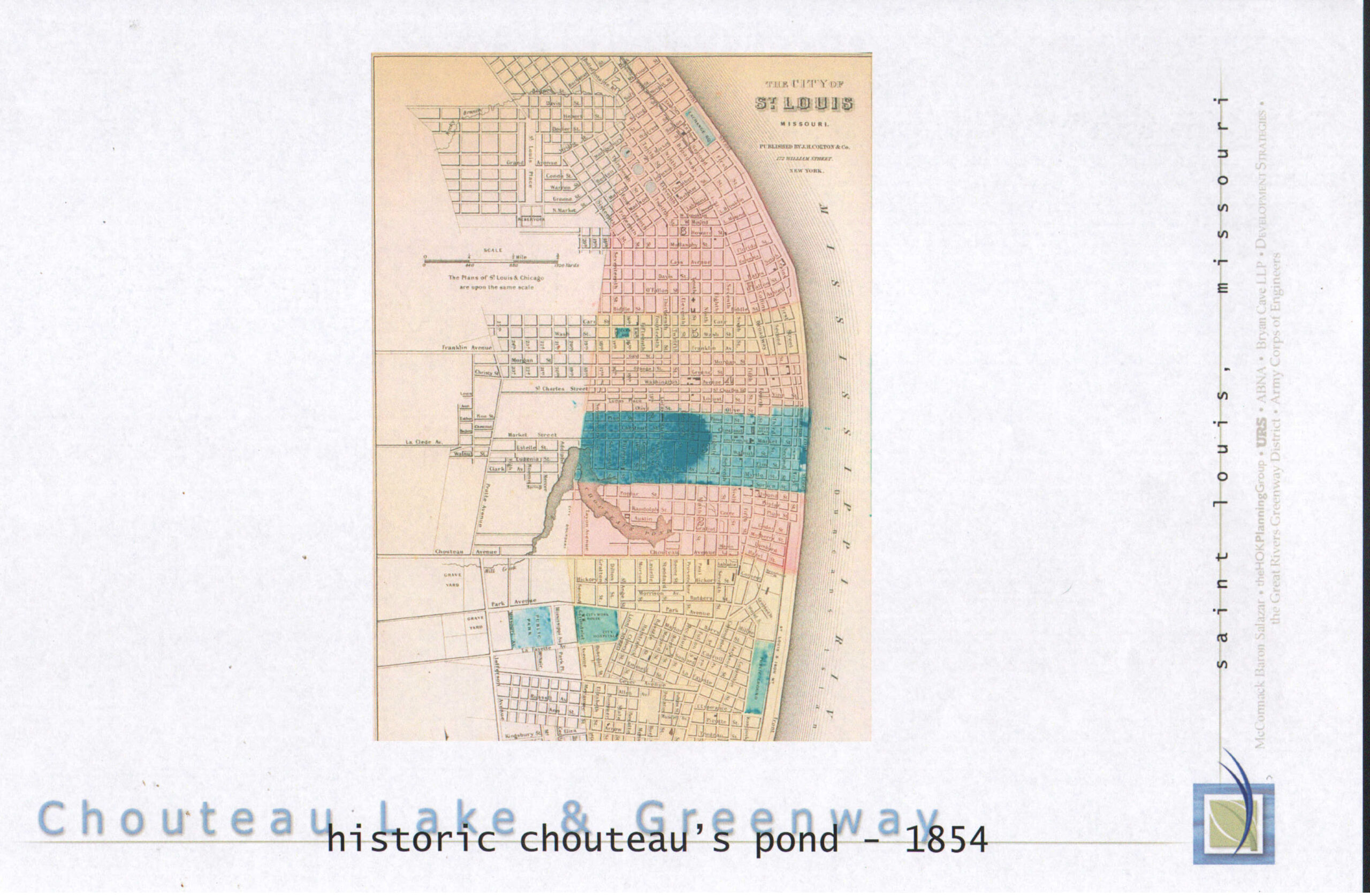

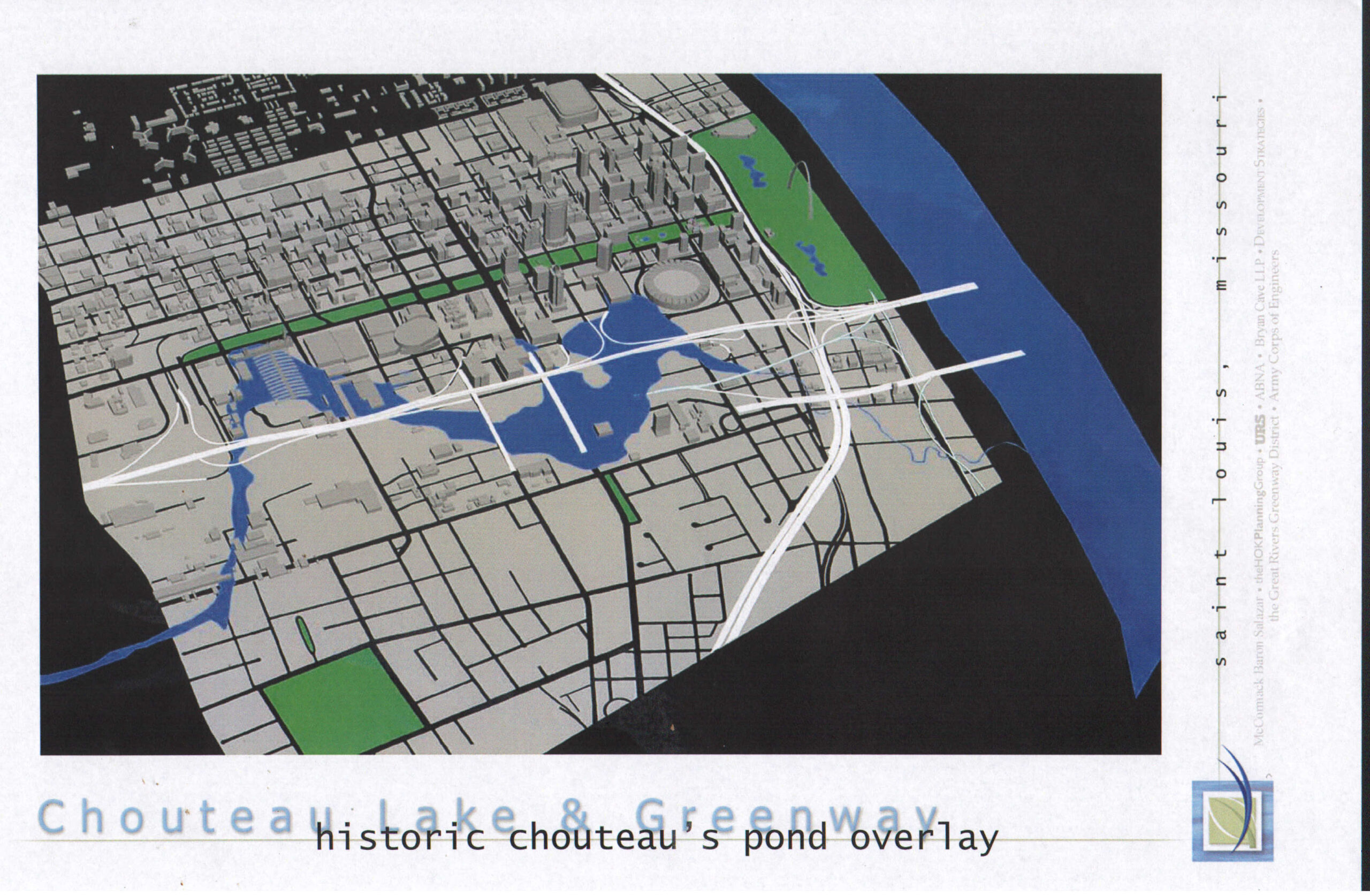

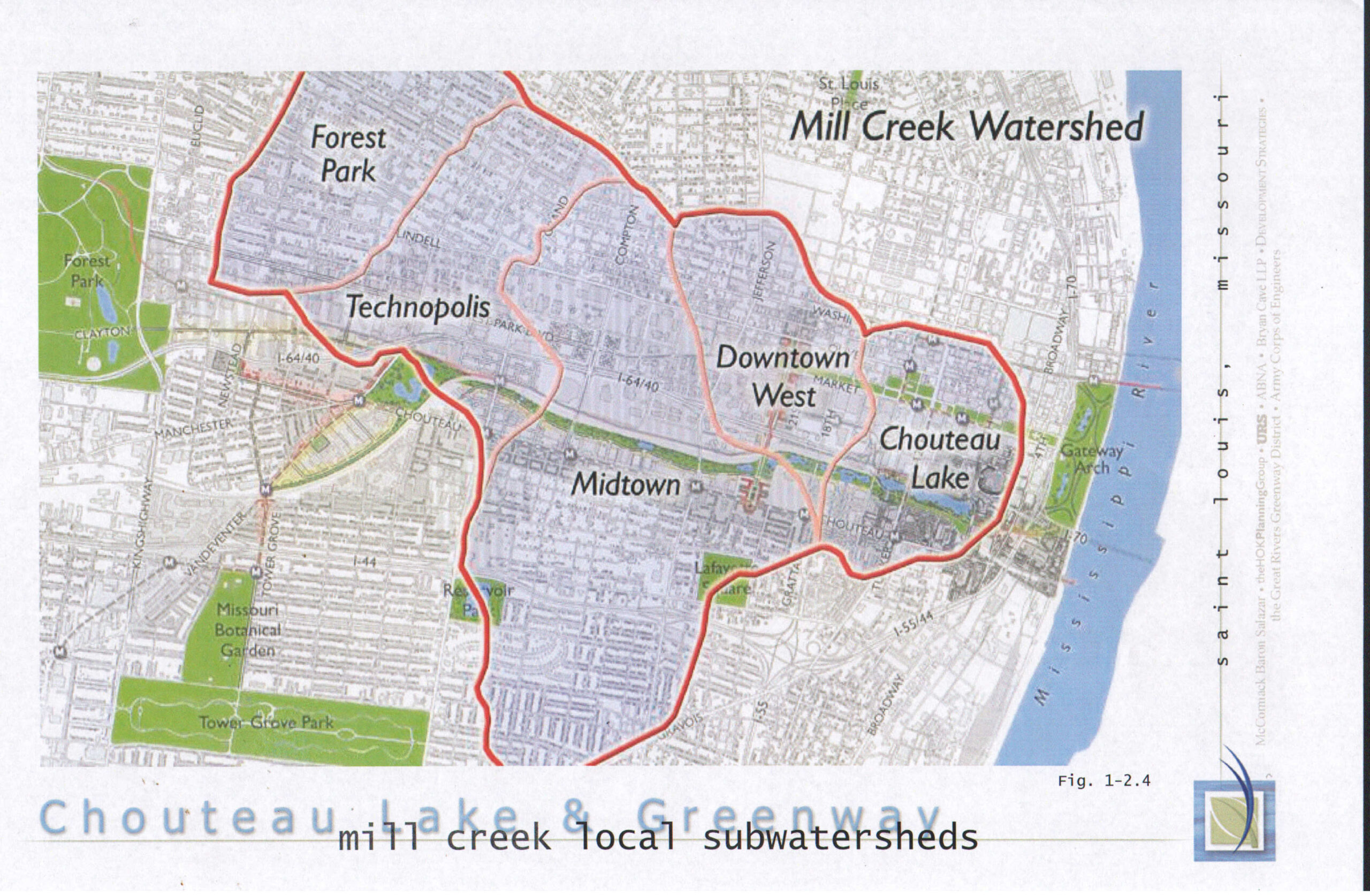

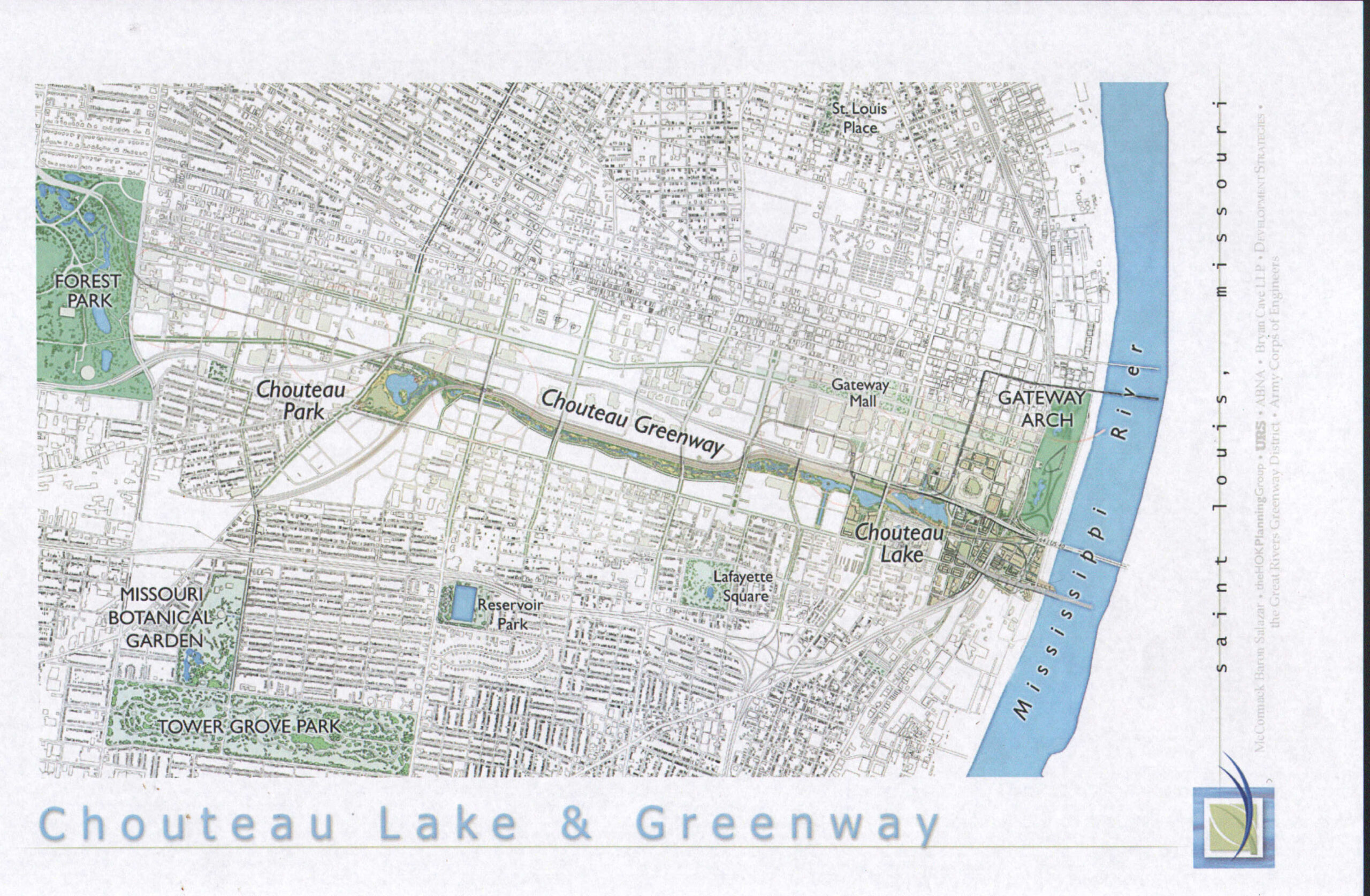

The origin of CLG started when we were doing the Westin Hotel, and that’s when I became aware of the former lake that was there that originally was created by the Chouteau family. When we engaged engineers to review the condition of the warehouses, they informed us that the buildings were slowly sinking because they had been built on fill used on the lake that had been there! So we had to drive sixty-foot pin piles to shore up the Westin Hotel warehouses.

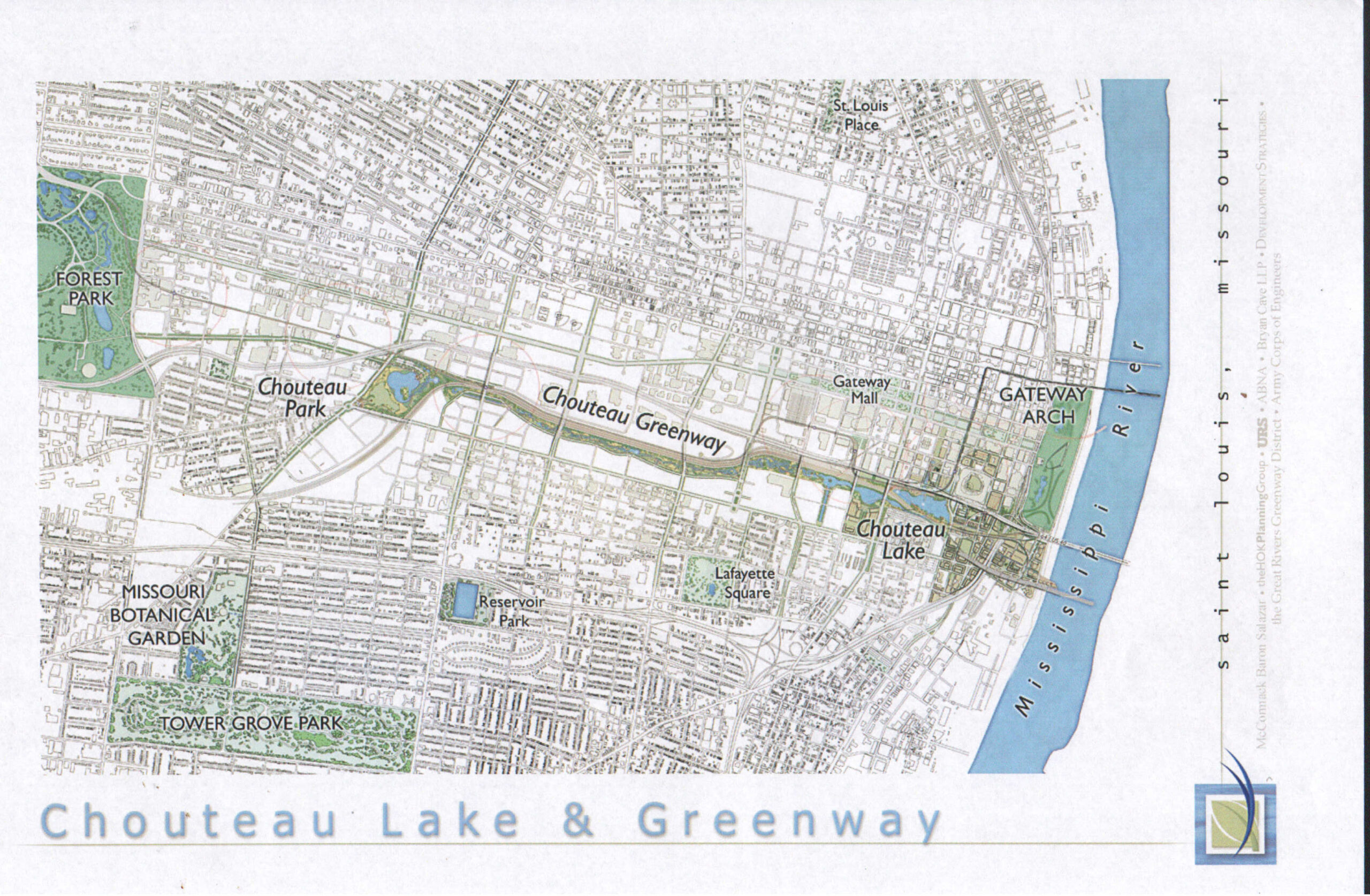

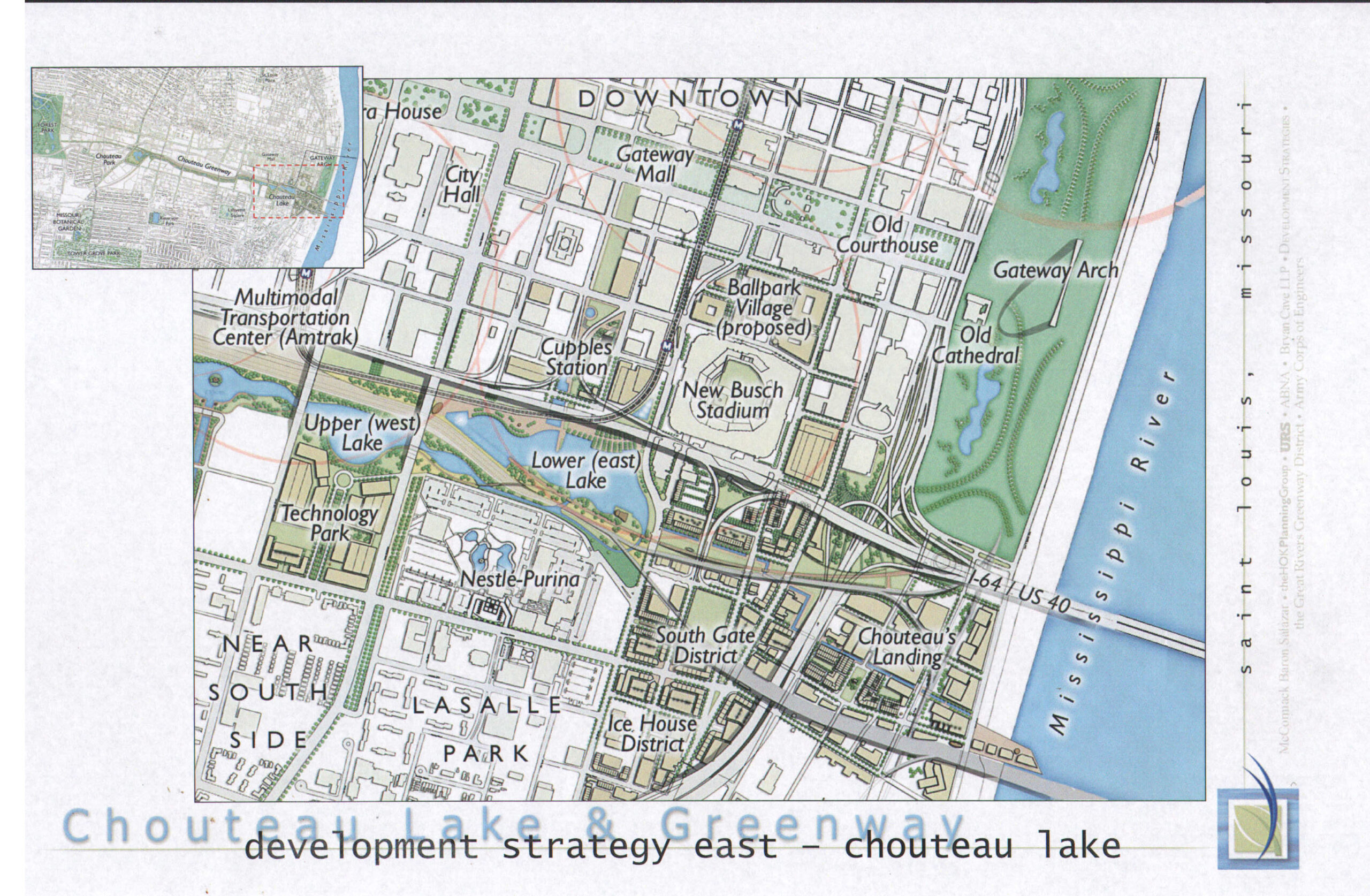

But, the impetus for it came from Gyo Obata, who I knew, and who HOK (Obata’s architecture firm) had been retained by Ralston Purina at a point in time to think about the north facing side of their corporate headquarters. He had been thinking about adding some sort of water feature, because he was aware of the original Chouteau Lake. That led me then to think about— wouldn’t it be great if we could put that lake back in Downtown?

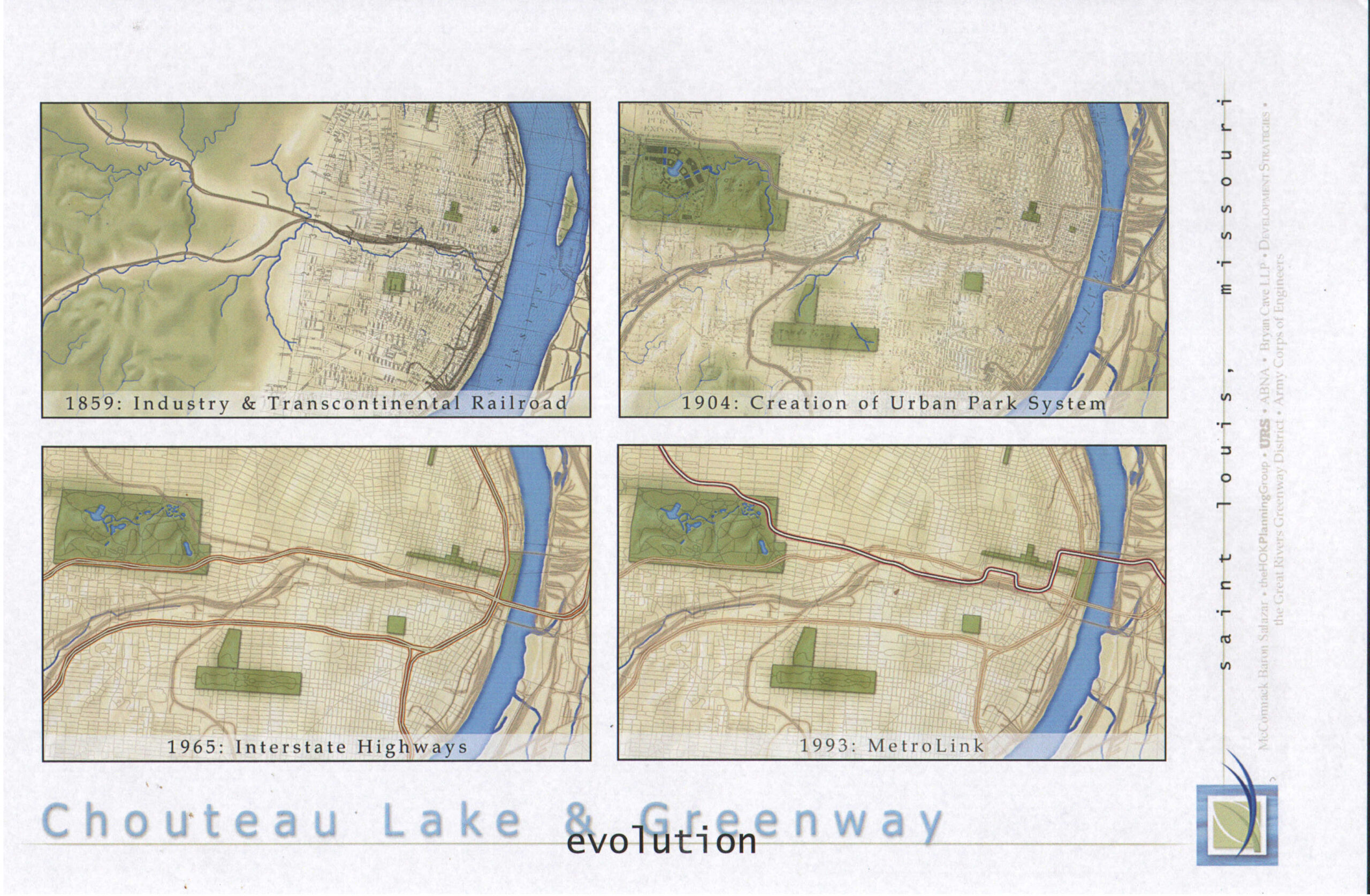

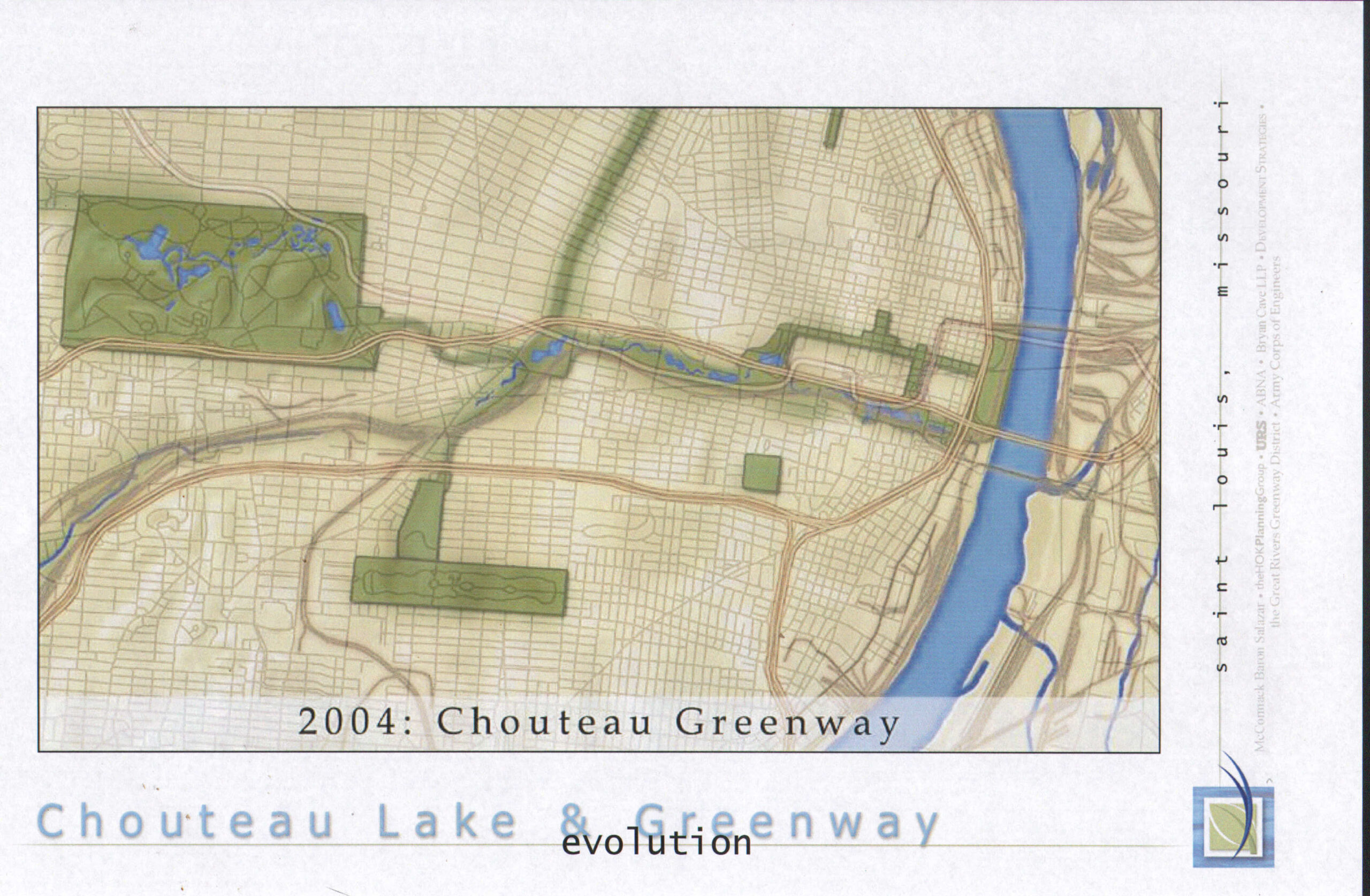

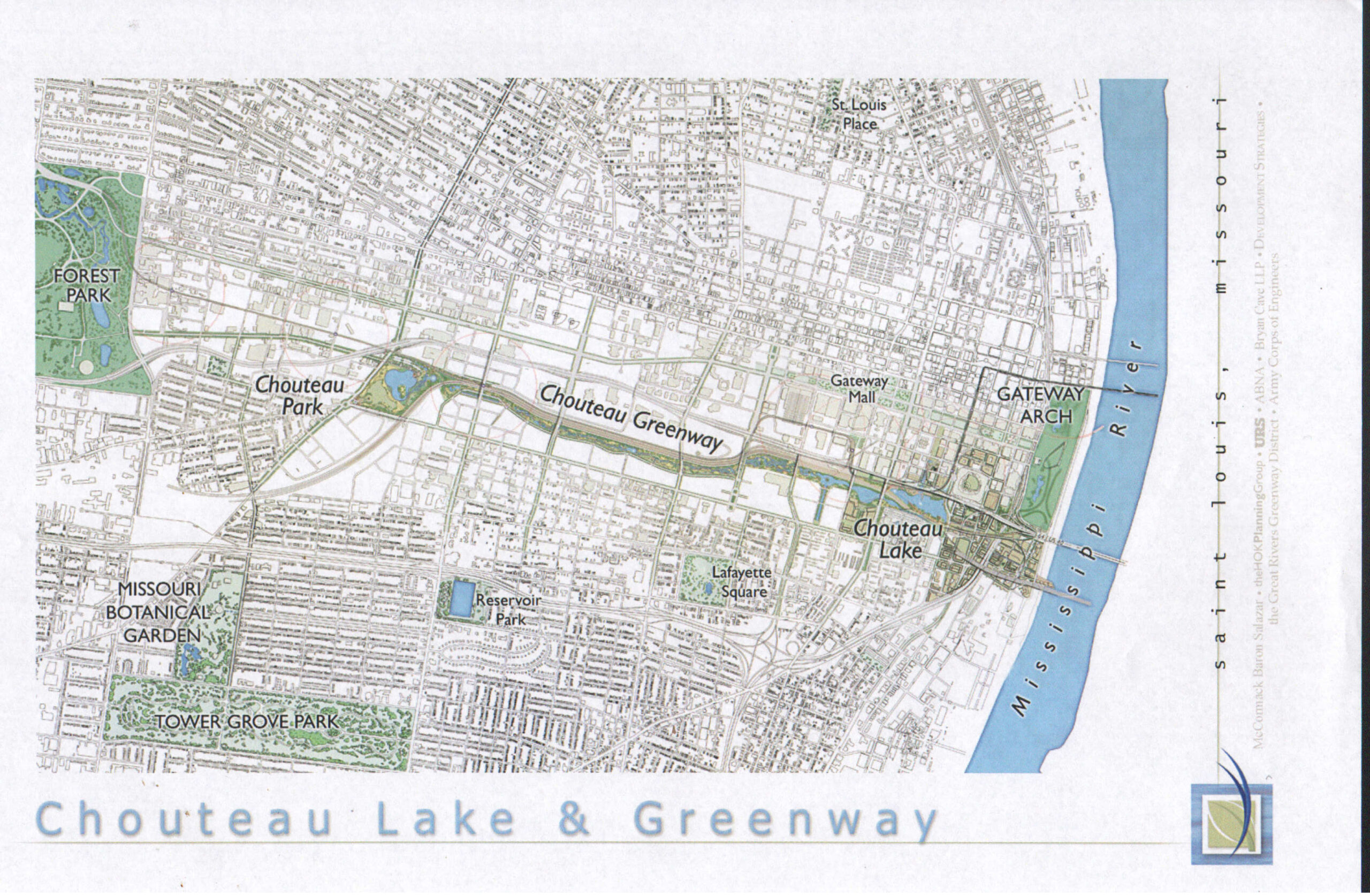

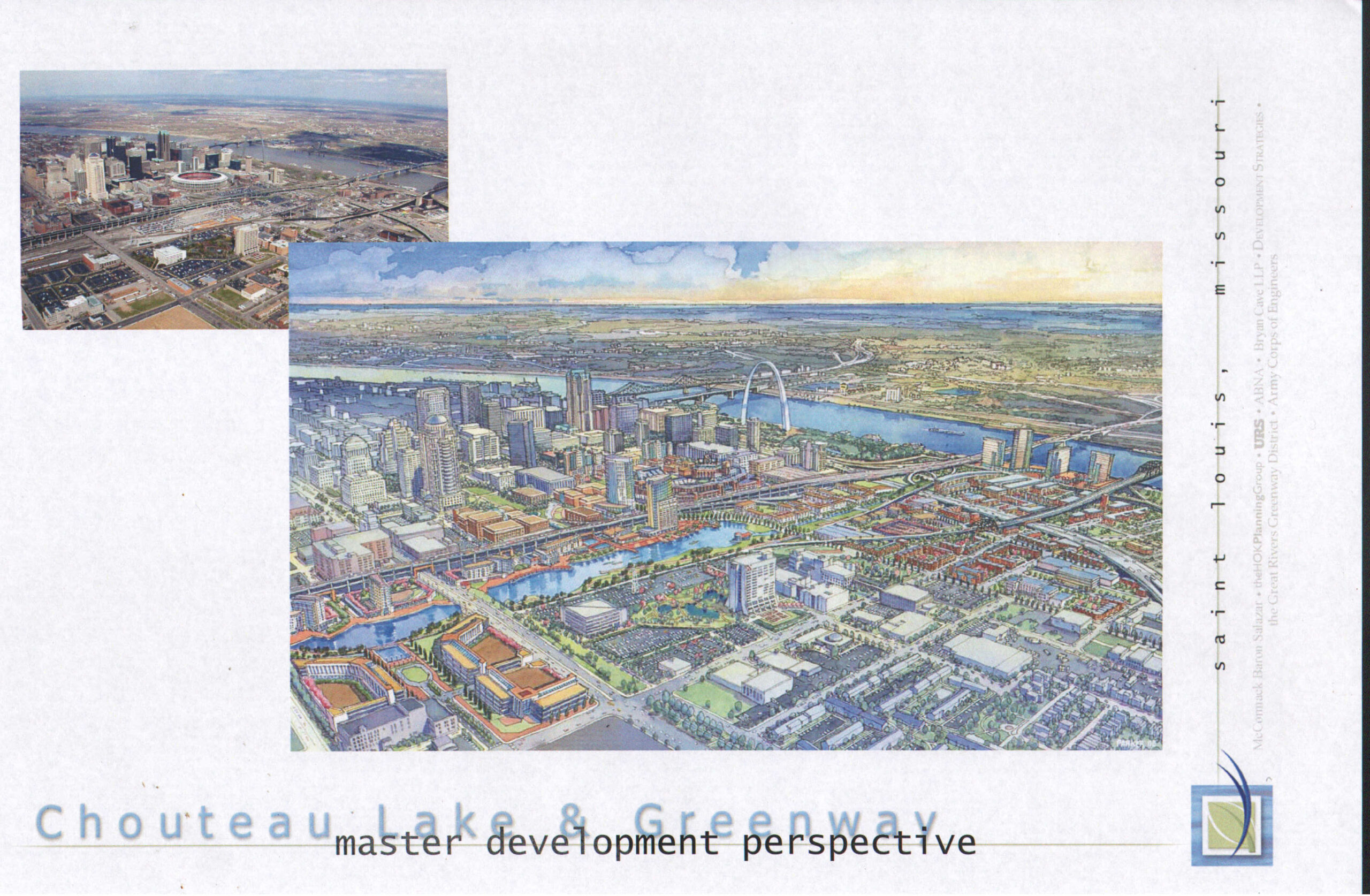

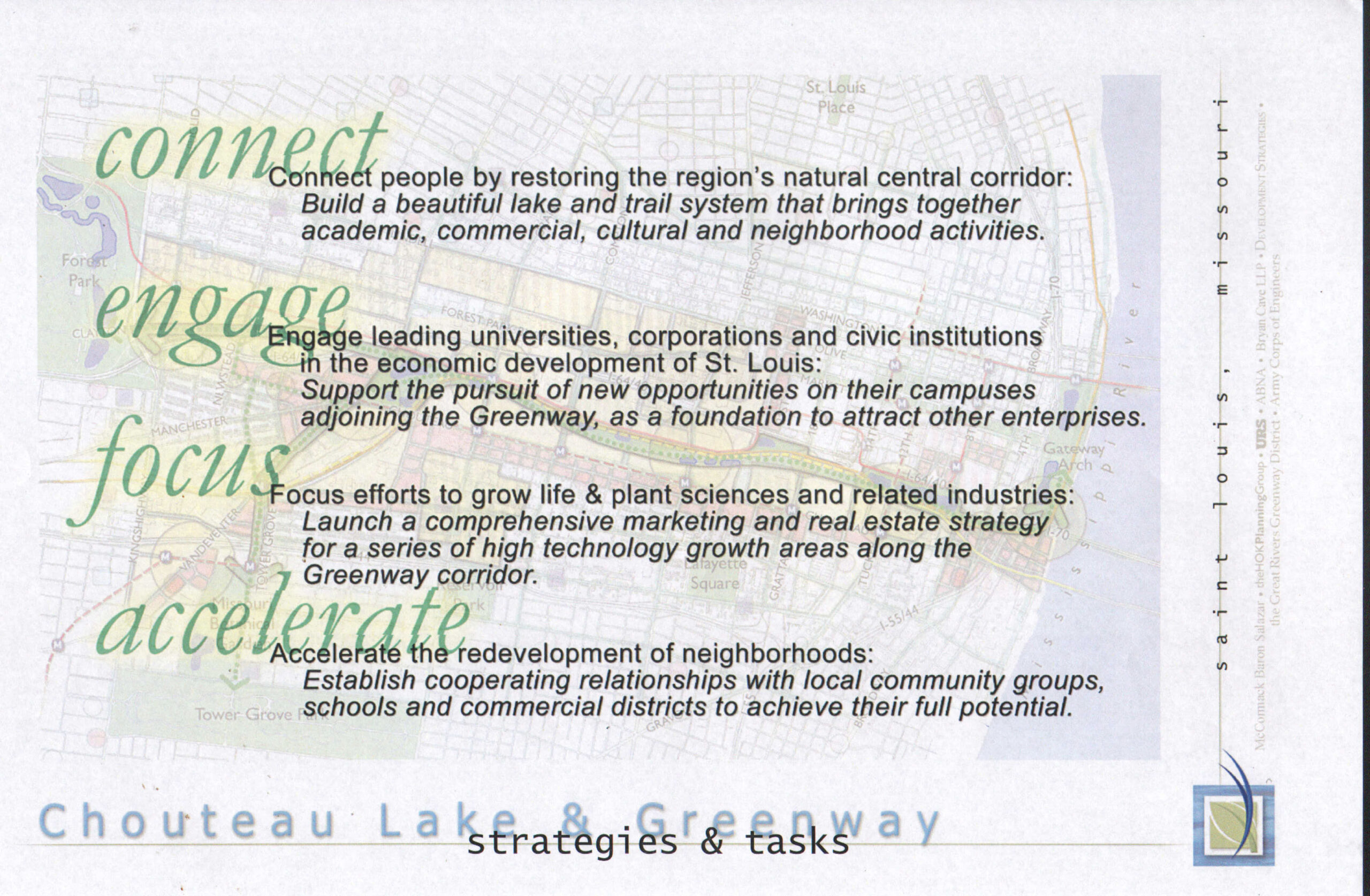

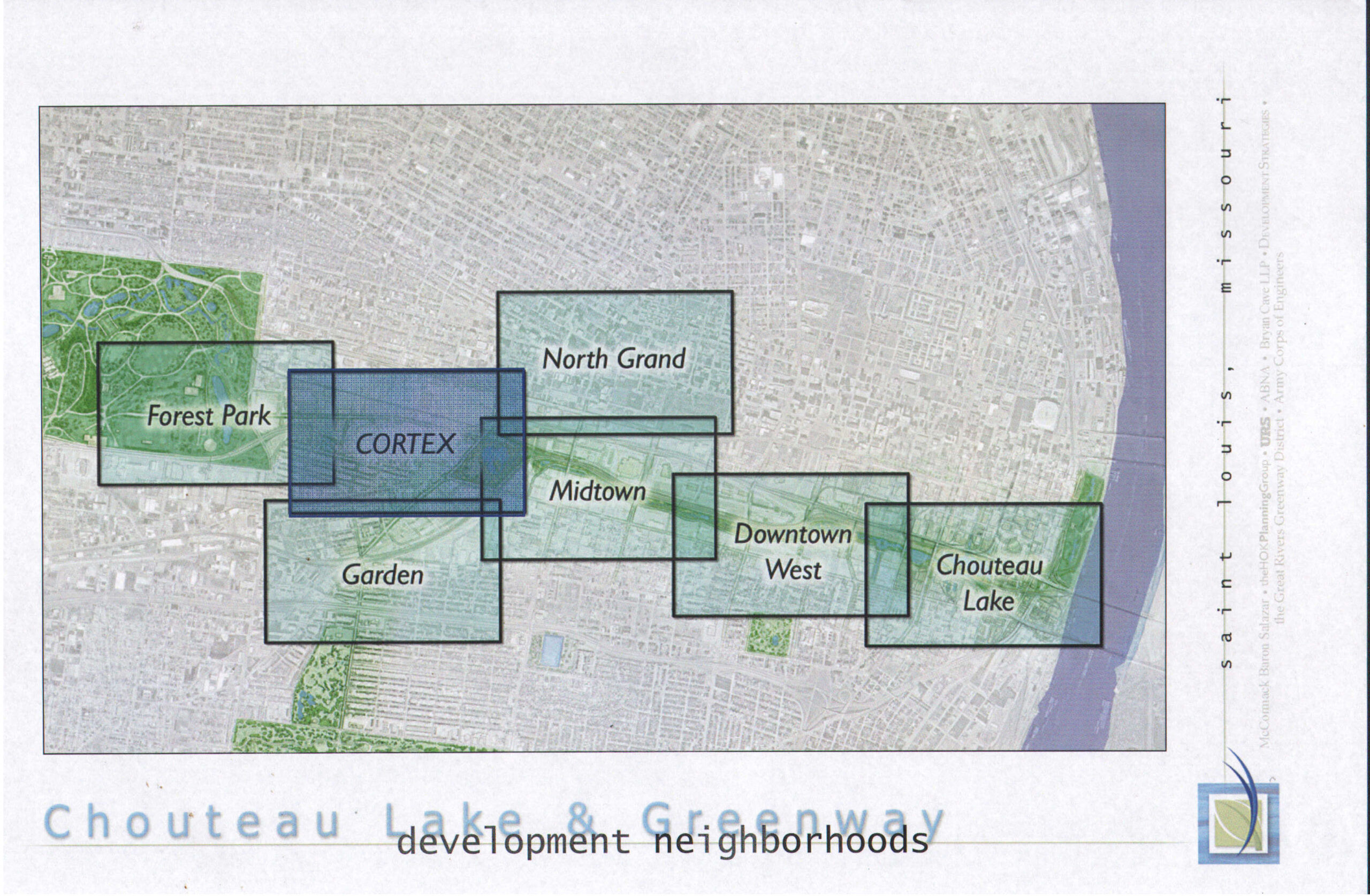

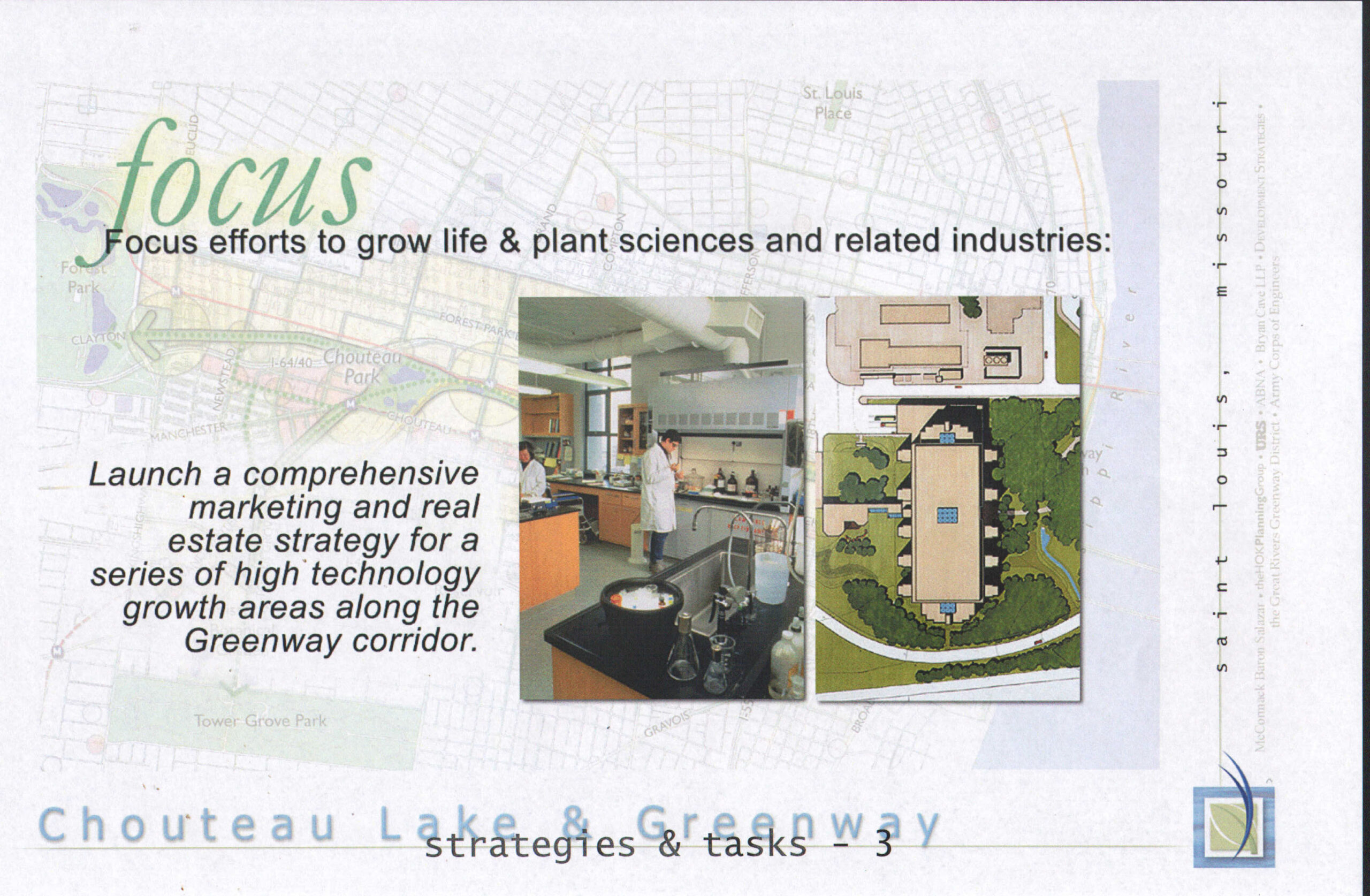

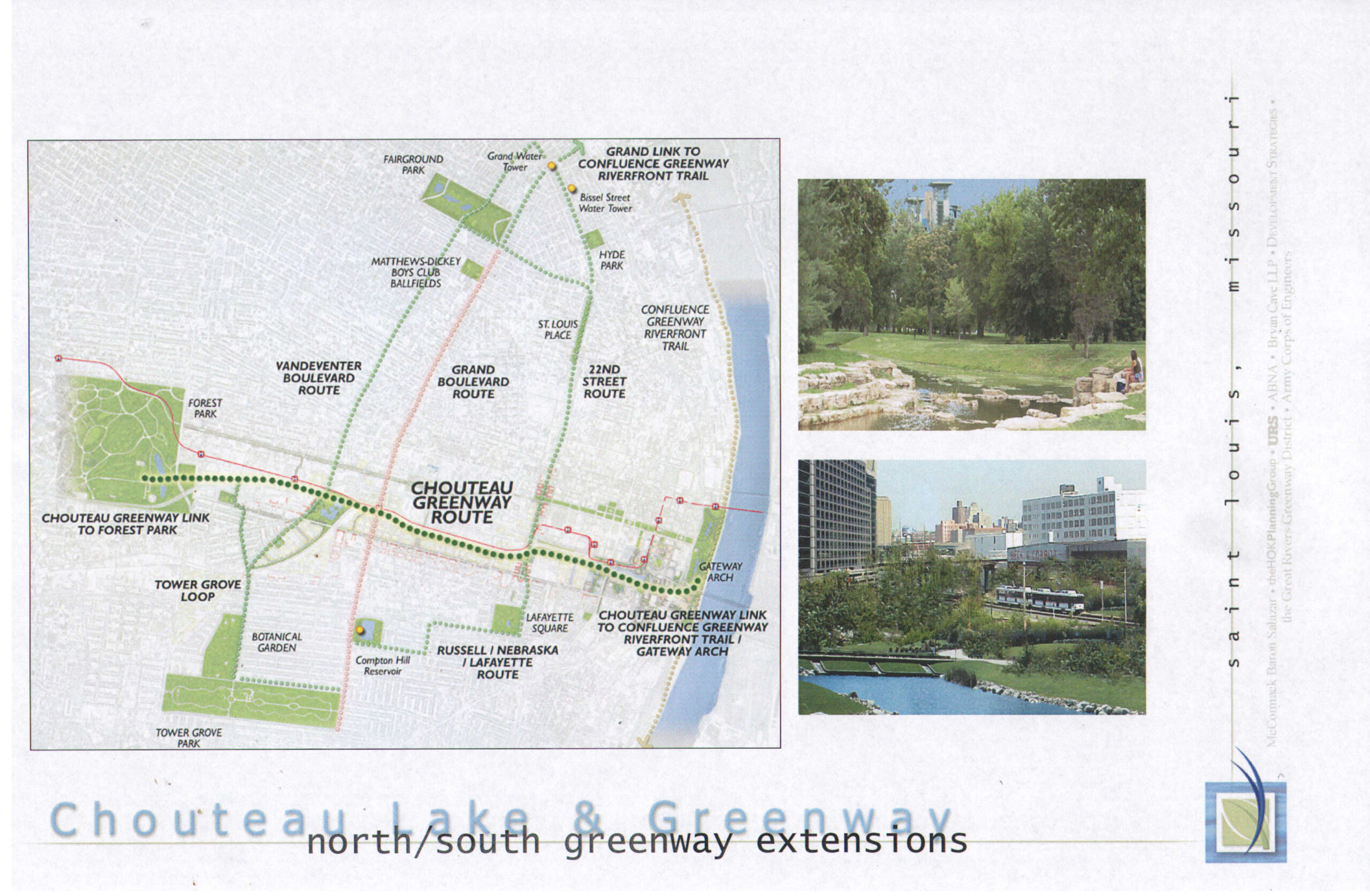

And then–if we’re going to do that, why don’t we think about this whole railyard? I mean, what was even happening there? I was aware of some of the projects that had happened in Denver with the railyard there. And, then I started doing research. Stephen Mulvihill, who you mentioned in your article, was here. He was our project manager on it and we turned up greenway projects that had been done in Seoul, Korea and in Copenhagen. And you know, all of a sudden we’re seeing these cities that are reclaiming their railyards and turning them into really great projects.

On support for the project

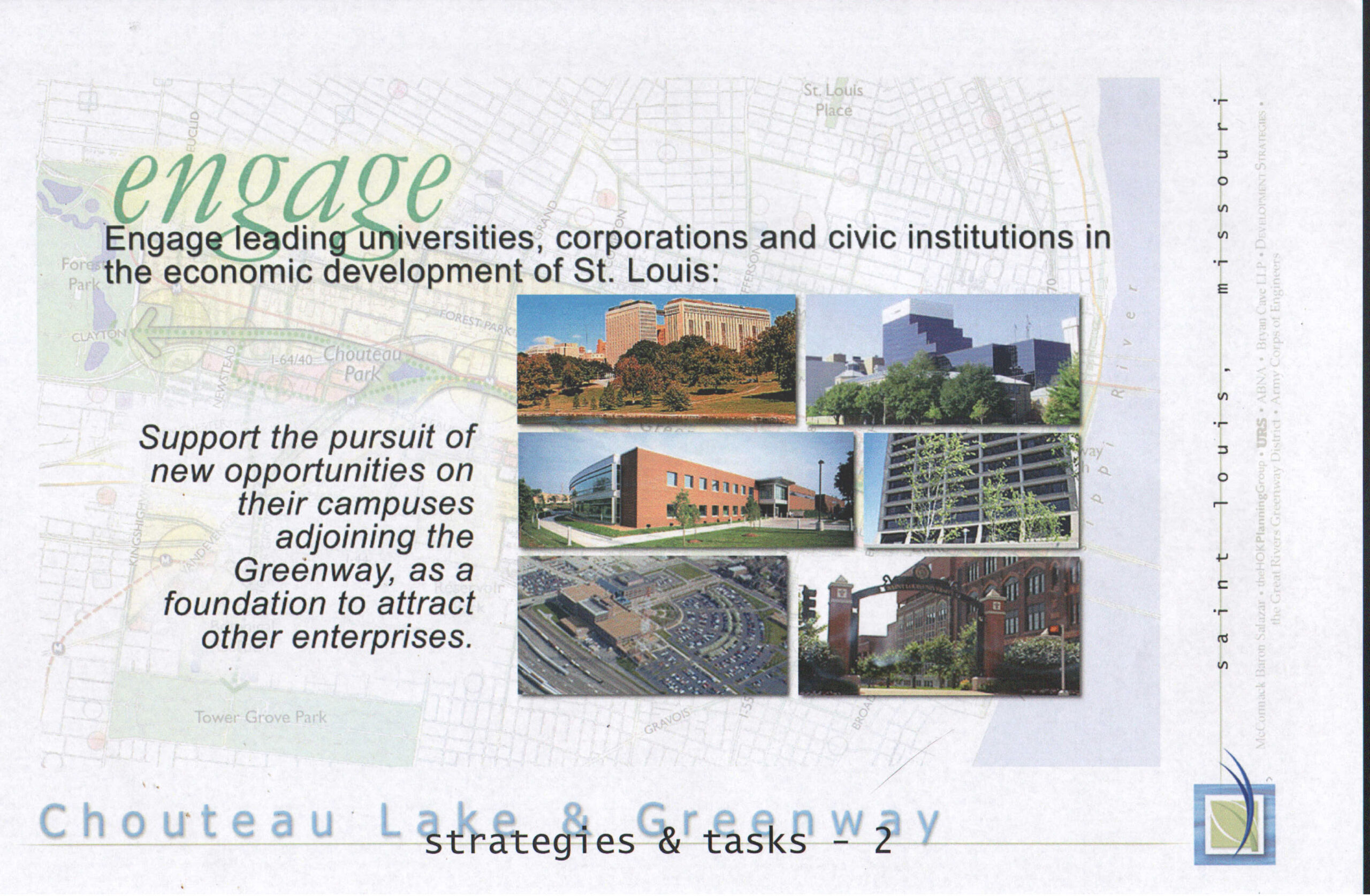

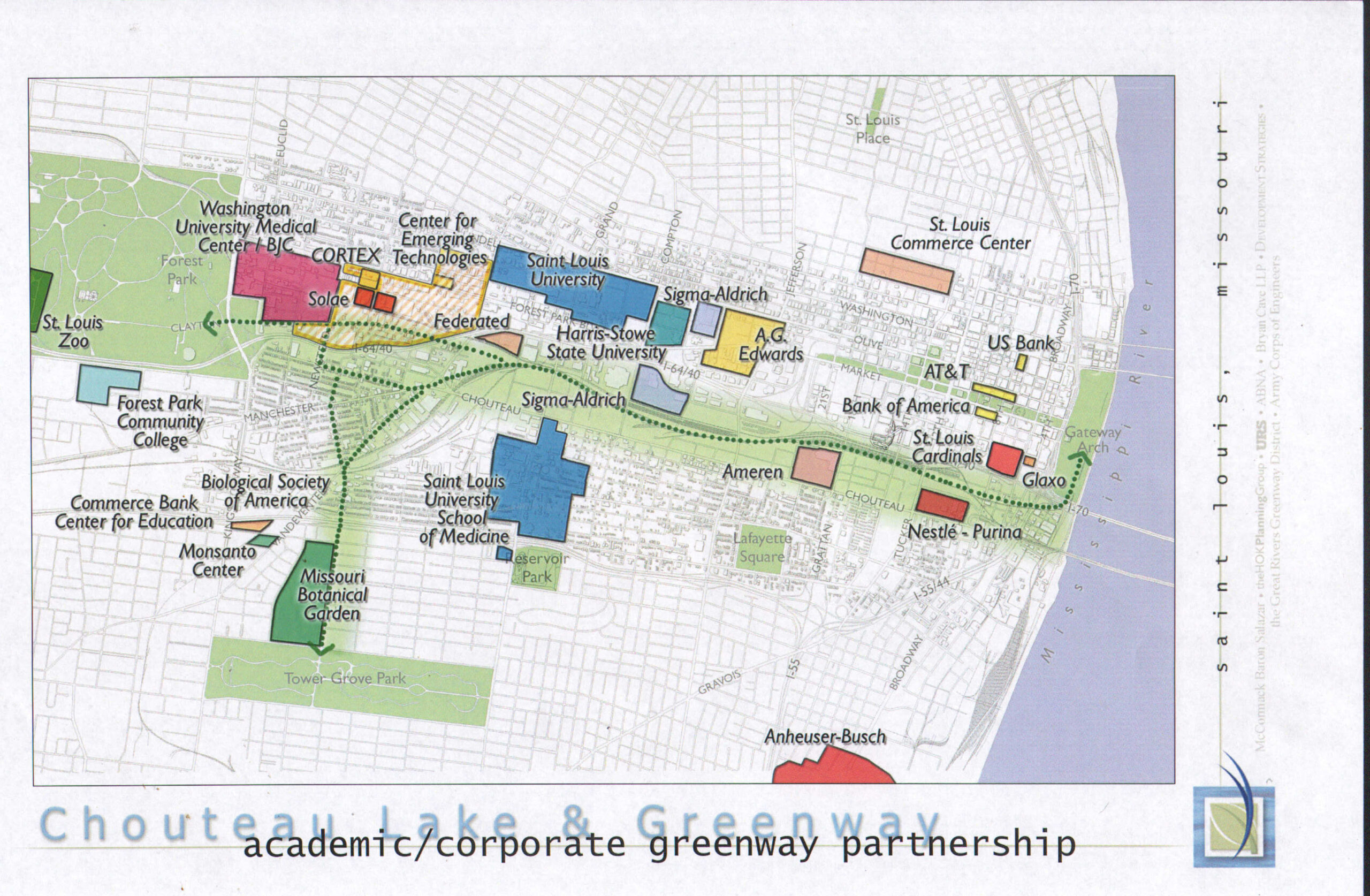

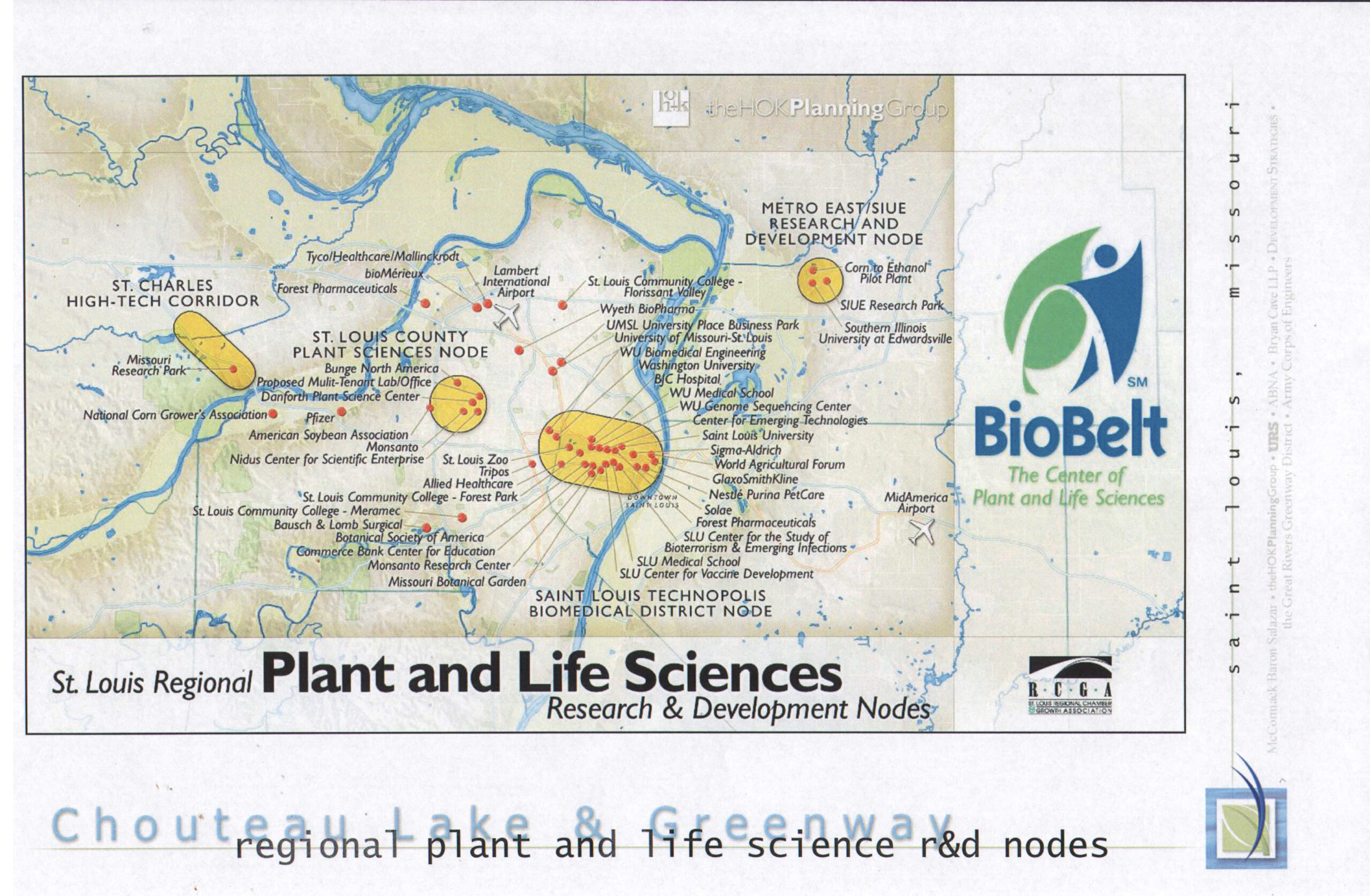

So then I went to HOK who then had a very robust facilities group there led by I think his name was (Jim) Fetterman. And we got into studying this whole idea. And at that point, I had gotten David Kemper (Commerce Bank) very interested, and Cindy Brinkley who was then the the head of Southwestern Bell before they became AT&T. We then got the president of Edward Jones interested, then we got McGinnis at Ralston, and we got the CEO of Ameren–very interested–of course, because they’re right on it– and then four or five other companies.

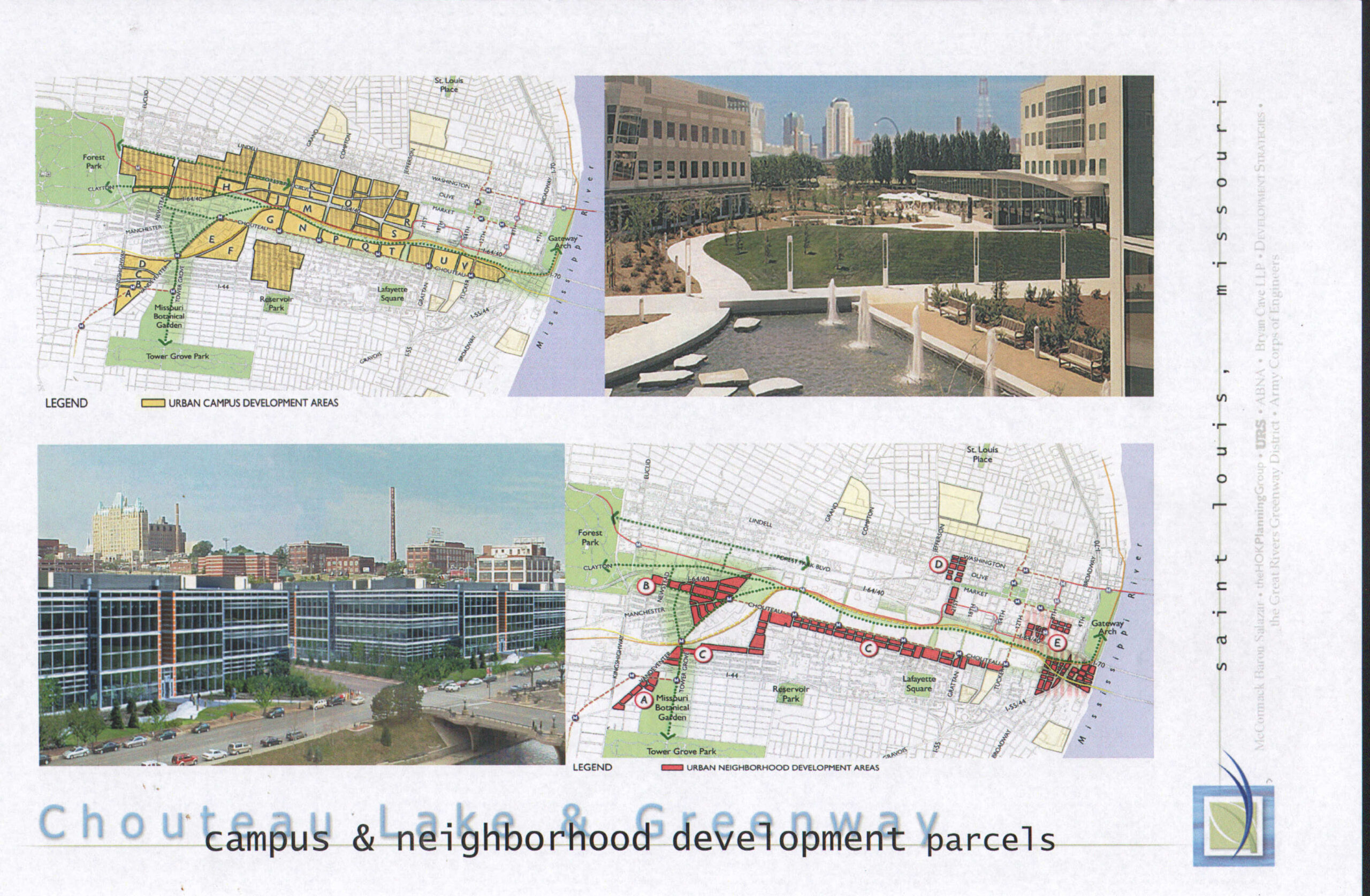

And (Father Lawrence) Biondi–I was on the board of SLU at that time–Larry, loved it. And I don’t know if you know the very contemporary research building he did on Grand and Chouteau that Cannon did for him. That was going to be back in the medical center area. Okay. And when I showed Biondi this plan, he said, this is great. There was 2500 acres of vacant land on that rail yard. And Biondi says I’ll bring the building forward to Chouteau and if this project really goes, I’d love to look at the railyard for expansion for SLU.

The Cardinals baseball team was completely on board. Mark Lamping was the general manager of the Cardinals at that point. Mark was involved in the meeting. The Cardinals loved the idea. I mean, having a lake sitting there adjacent to the stadium? People can come down to the ballpark and picnic around the lake.

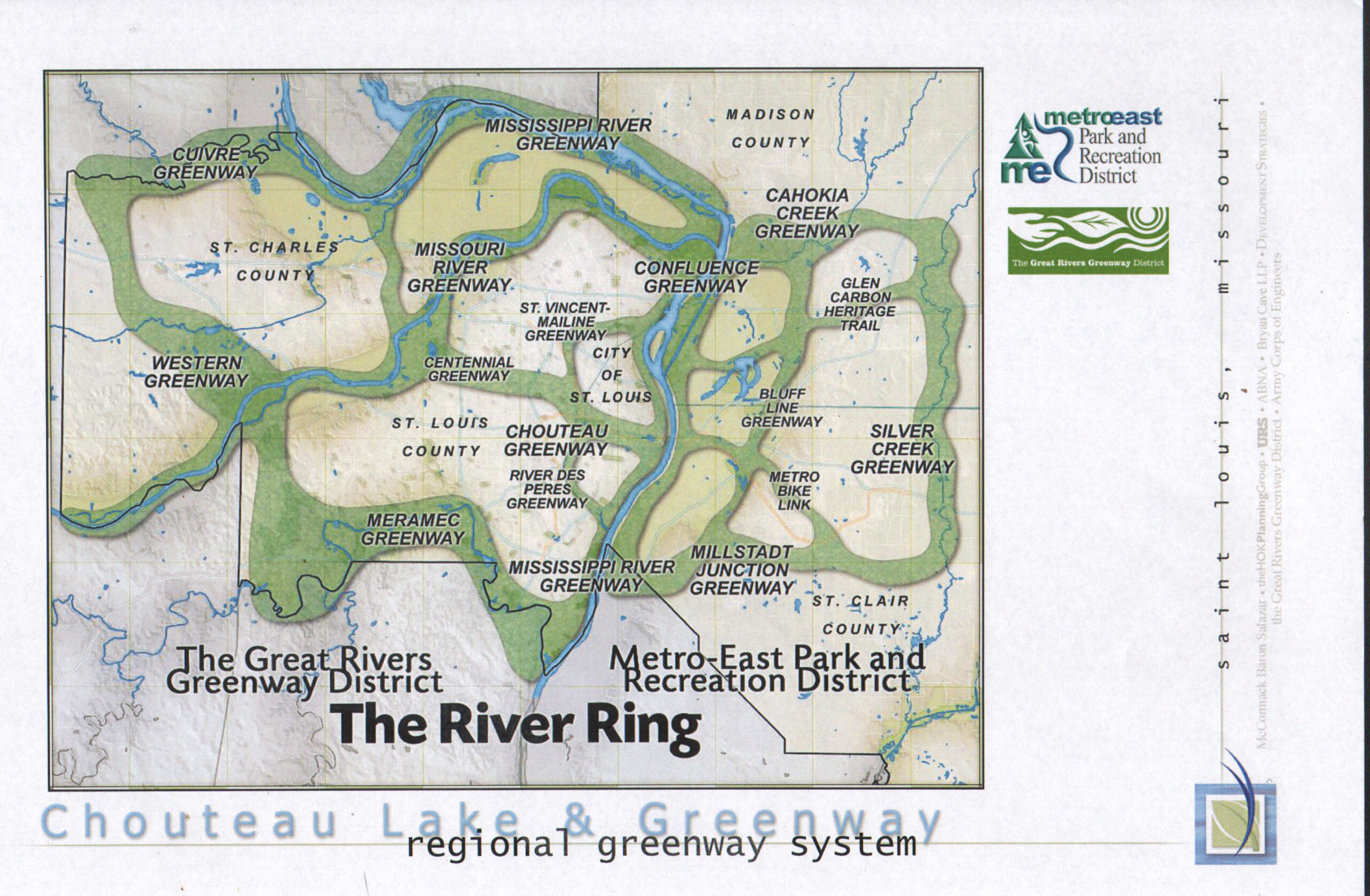

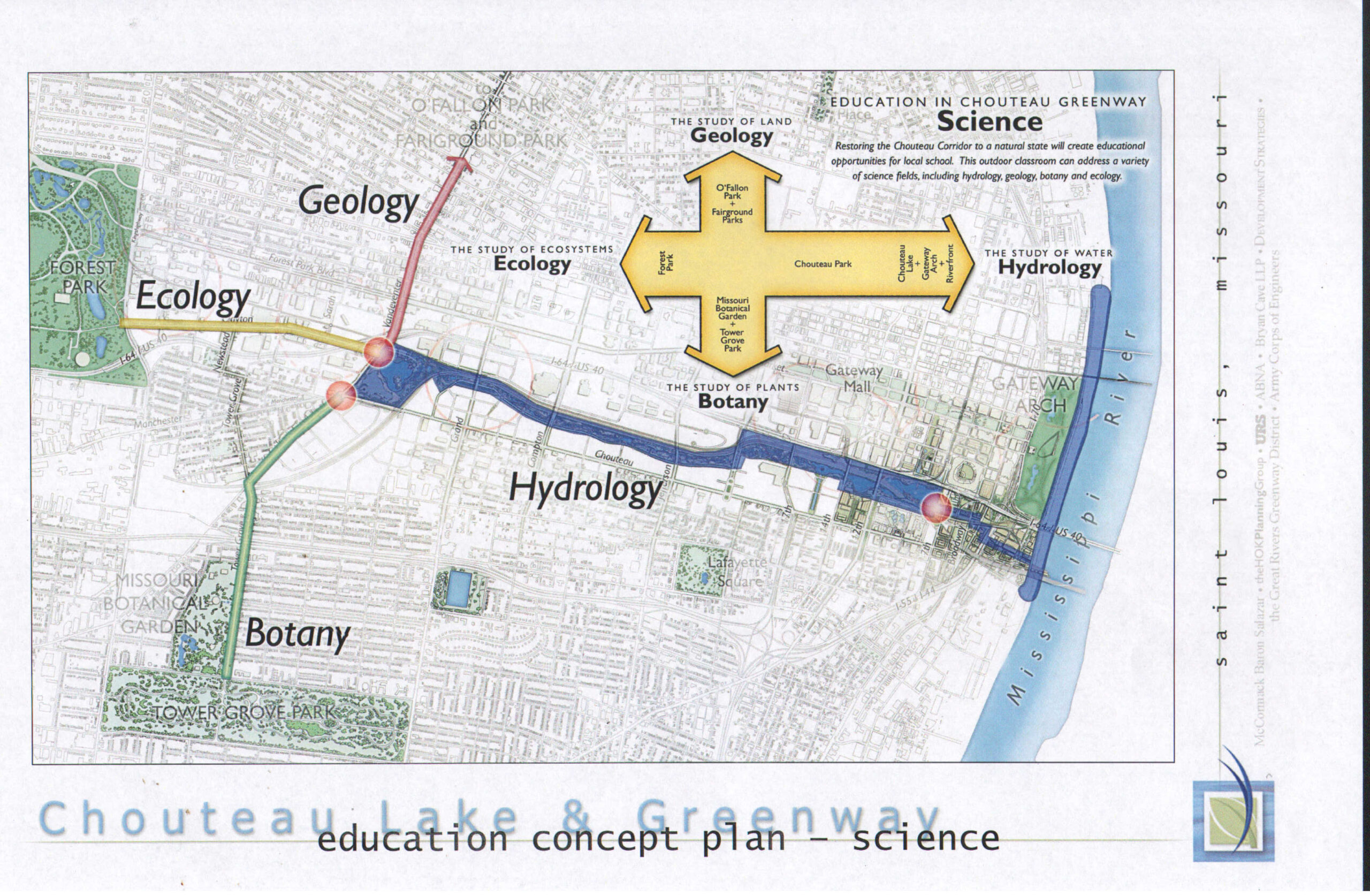

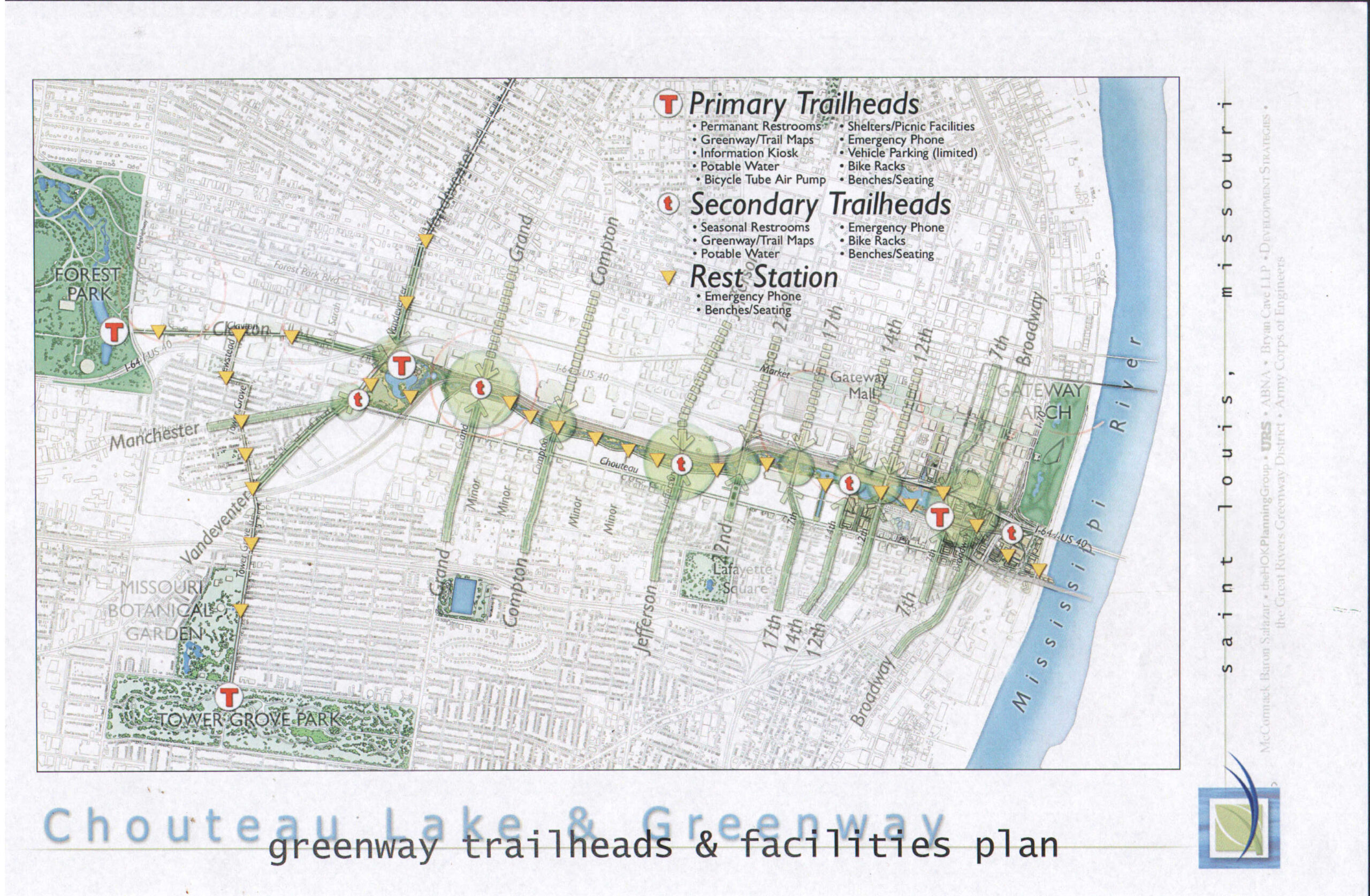

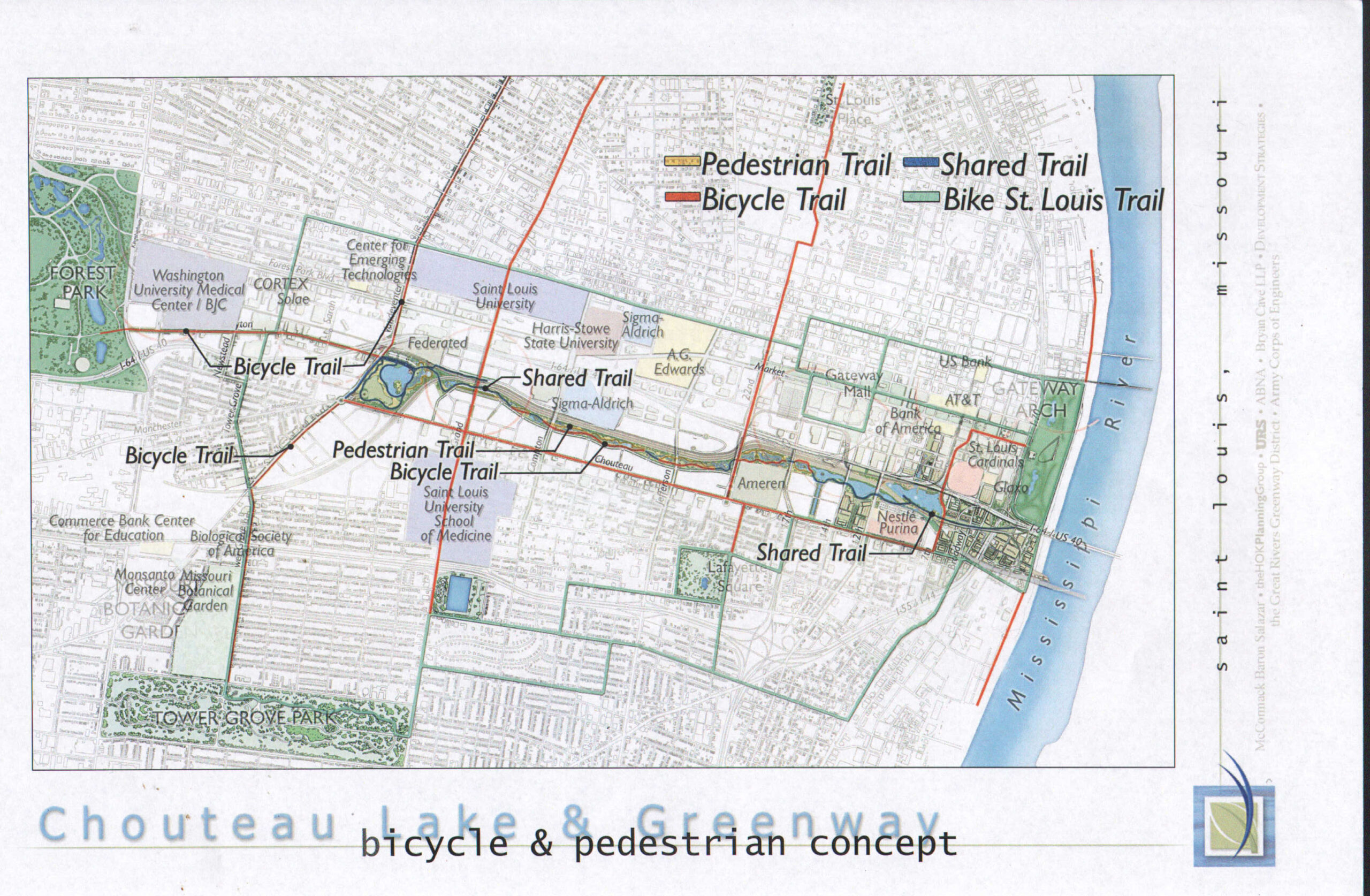

(Former Missouri Senator Kit) Bond was completely supportive. He loved it. And he understood the river and the whole project. As former governor, I mean, he really understood. Then, I sat with (Barack) Obama, who was then senator, and he and I met several times about it. And what he said was look If you can bring the trail around and come down through East St. Louis, he said it would be great and it would really give him a way to to add some help for the city, and it would be a great enhancement there. So we added a link around–So that you literally could go all the way around, come back here, and go out to Forest Park. And at the end of the day, I think it was like 15-20 miles. It was terrific.

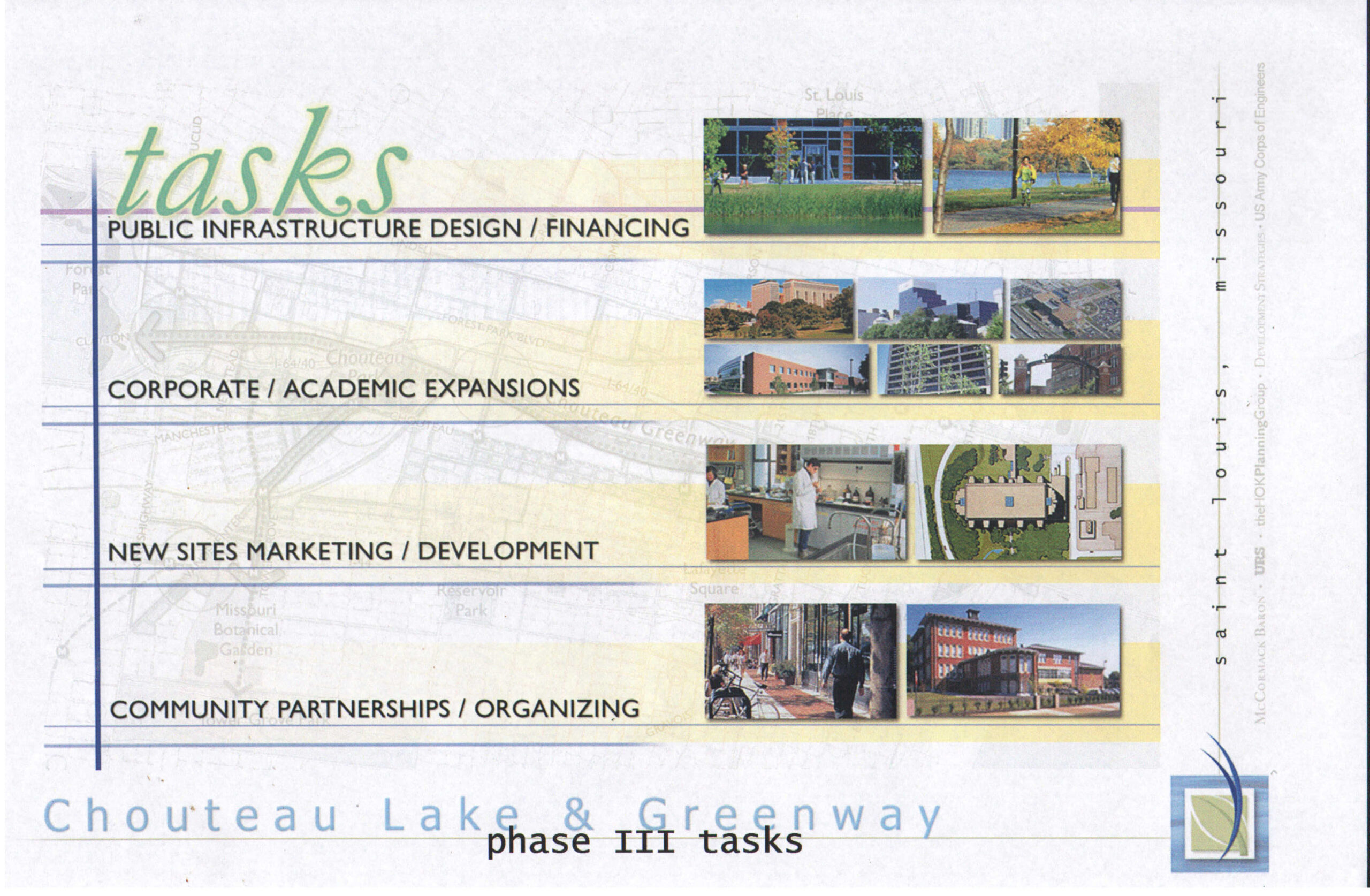

This–just so you and I are clear–this was not some kind of visioning exercise that got HOK’s facility staff to do some pretty pictures for me as eyewash to go around and show people the possibilities. We had designed an engineering program to reinvigorate the railyard, relocate that track, put the lake in, and run those trails out to Forest Park and then up to the confluence. We had it all engineered.

On the challenge of the railyard

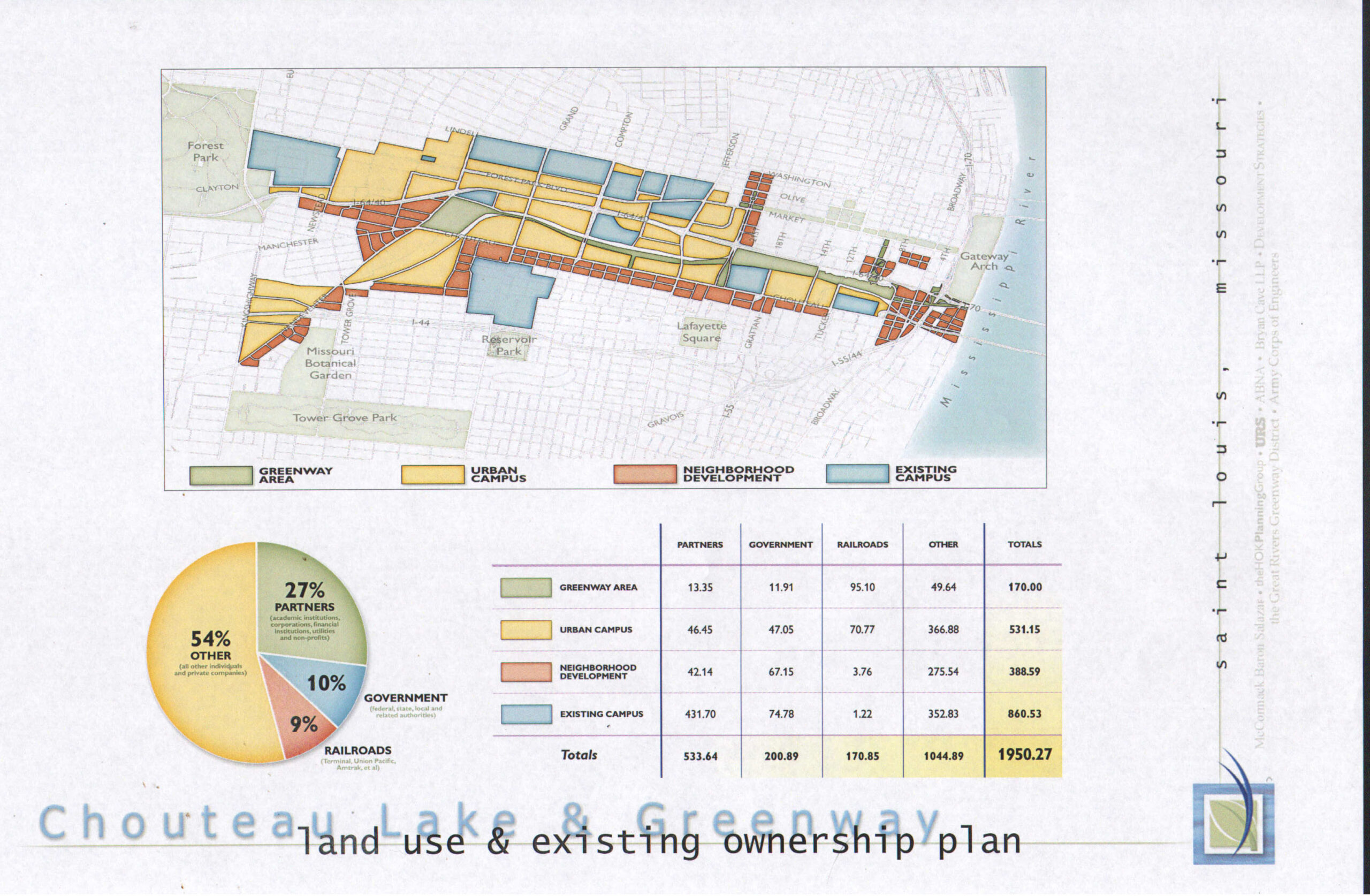

We raised, I think it was a couple million dollars, from all these local business leaders to do the engineering. HOK brought in two or three subcontractors who were railroad engineers to look at moving the track over to the north side of that expanse–from where it was.

So, Stan (Stephen Mulvihill) went to Omaha (to Union Pacific headquarters) and at that point in time three or four of the key executives of Union Pacific were St. Louis, born and raised, and they all went to school with (Former Missouri Senator) Jack Danforth at St. Louis Country Day. So, this notion that the railroads killed the CLG–the absolute opposite was the case. The UPRR facilities staff said, well look, there’s some cost involved here moving the track over but this has never been a yard that was serviced. This was basically storage. And there are more advanced areas over on the East Side in Illinois. Those facilities are all computerized now.

And the railyard wasn’t dirty dirt at all. There was no gas or oil here or anything else. It was just a storage facility in effect. And yeah, we can move the track over and yeah it wouldn’t be a big deal, but we’re going to have to have some compensation. They were totally amenable to it. They were totally on board.

The Chouteau Lake & Greenway plan book

On the project’s demise

So we have this meeting in the boardroom of Southwestern Bell. I can’t tell you exactly what date it is. Stan (Stephen Mulvihill) may remember. We’re sitting there– Senator Bond, Cindy Brinkley, David Kemper, (Former Danforth Foundation Executive Director Peter) Sortino is there, (Deputy Mayor Barb) Geisman is there. Slay walks in and we start talking about the plan and moving forward.

And Slay basically says,– I want to make it very clear. I do not support this idea.

And I’m like–Francis, what does that mean?

And he basically says –Well, we don’t want any competition with the arch grounds and we’re not prepared to support this plan.

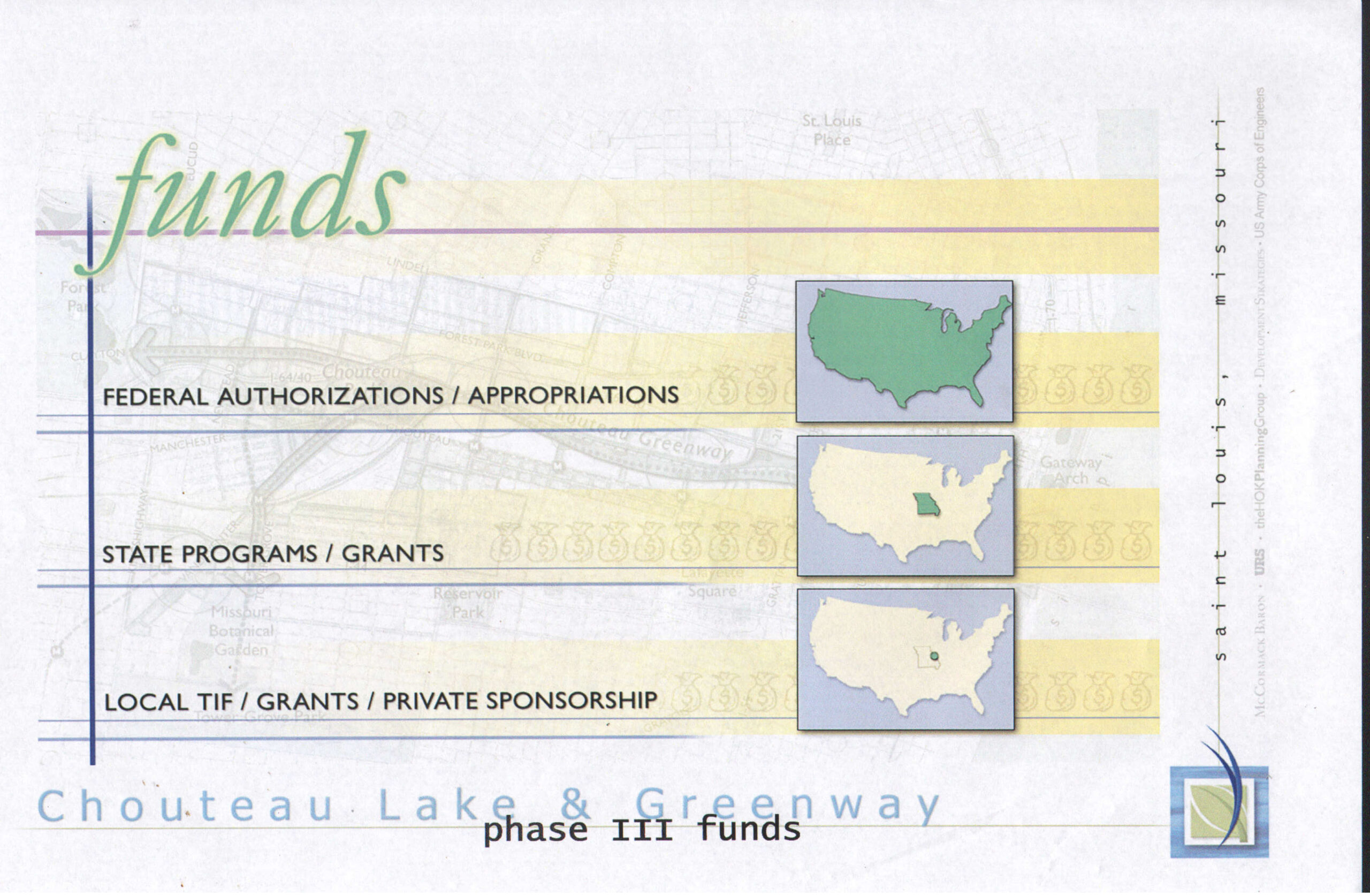

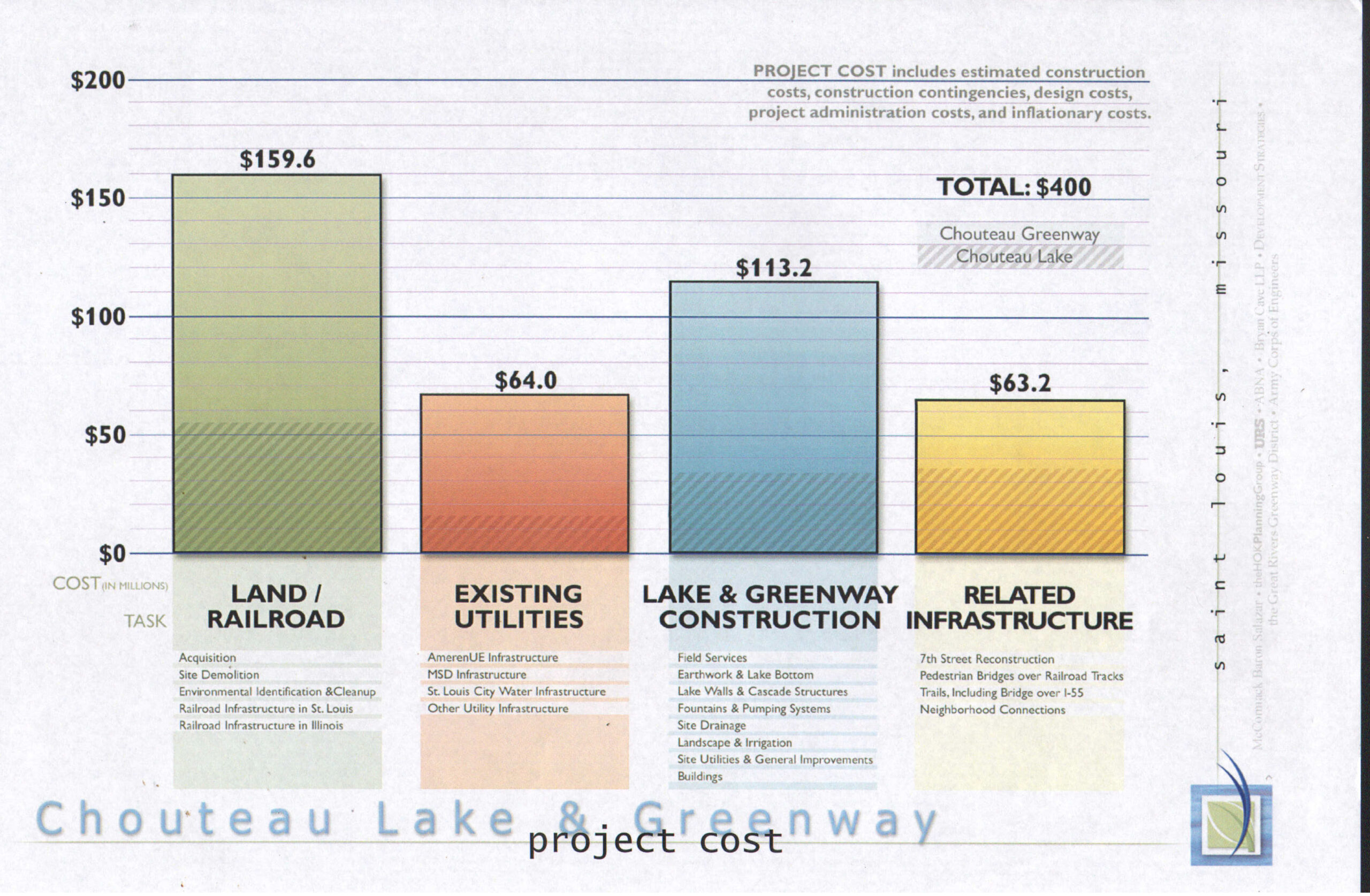

That’s it. We’re done. If the city would not support any requests of federal agencies, then we could not have put the funding (approx $400M) together. Just that simple. We can’t go to the feds without the city and Slay is saying he’s not going to support it.

These local leaders philanthropically could have put up all kinds of money just like they wound up doing for the arch grounds, or the art museum, or the symphony, or Forest Park Forever. But, once Bond heard that and Cindy and everybody, I mean It was the end of the story. I just basically threw up my hands and said you know we spent two years breaking ourselves on this project– putting the plan together, meeting with Union Pacific, talking with business leaders. I mean, it was absurd that we couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time here to do something like that for the city while still supporting the redo of the arch grounds.

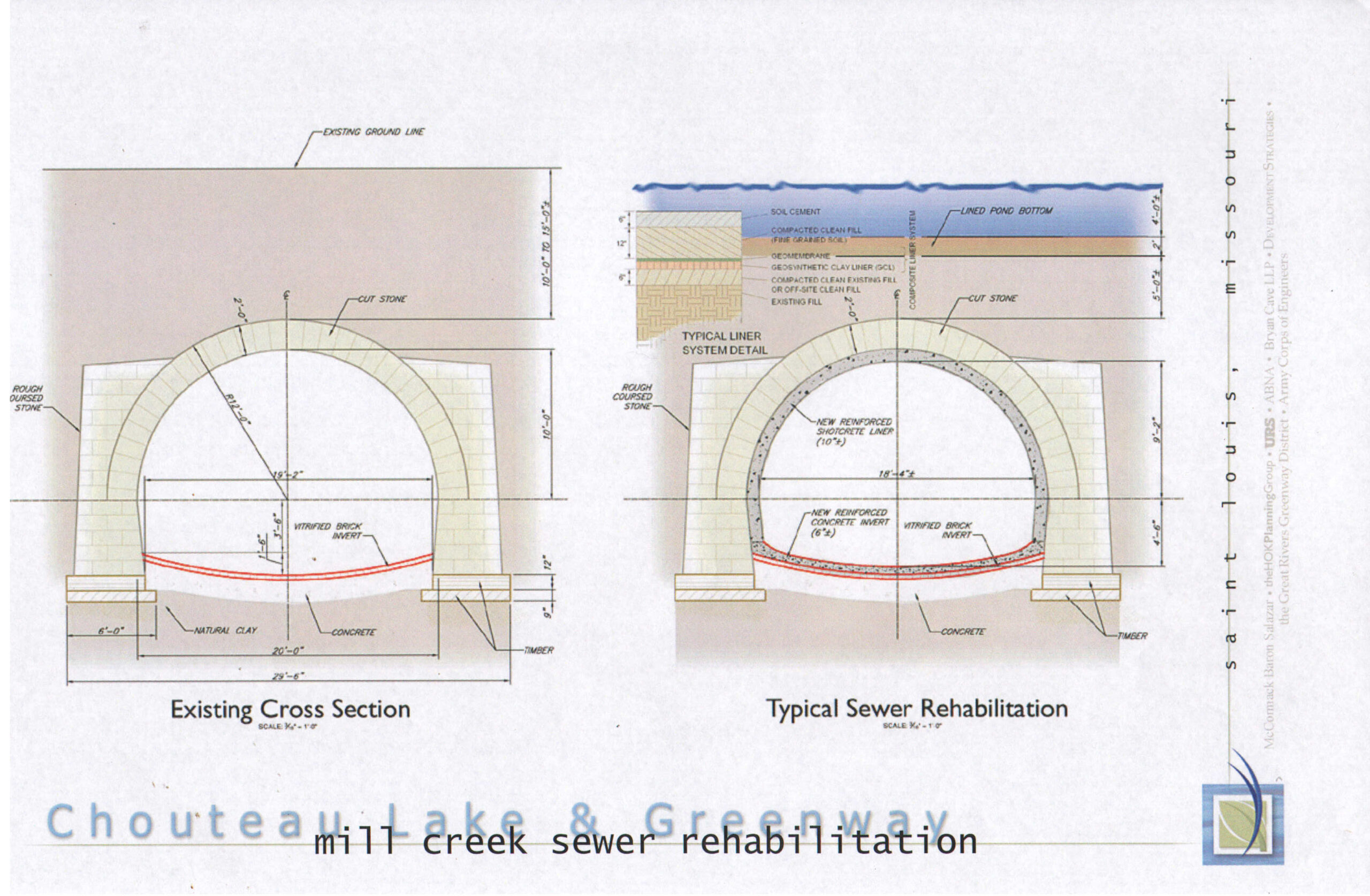

On the work that was done

This–just so you and I are clear–this was not some kind of visioning exercise that got HOK’s facilities staff to do some pretty pictures for me as eyewash to go around and show people the possibilities. We had designed an engineering program to reinvigorate the railyard, relocate that track, put the lake in, and run those trails out to Forest Park and then up to the confluence. We had it all engineered.

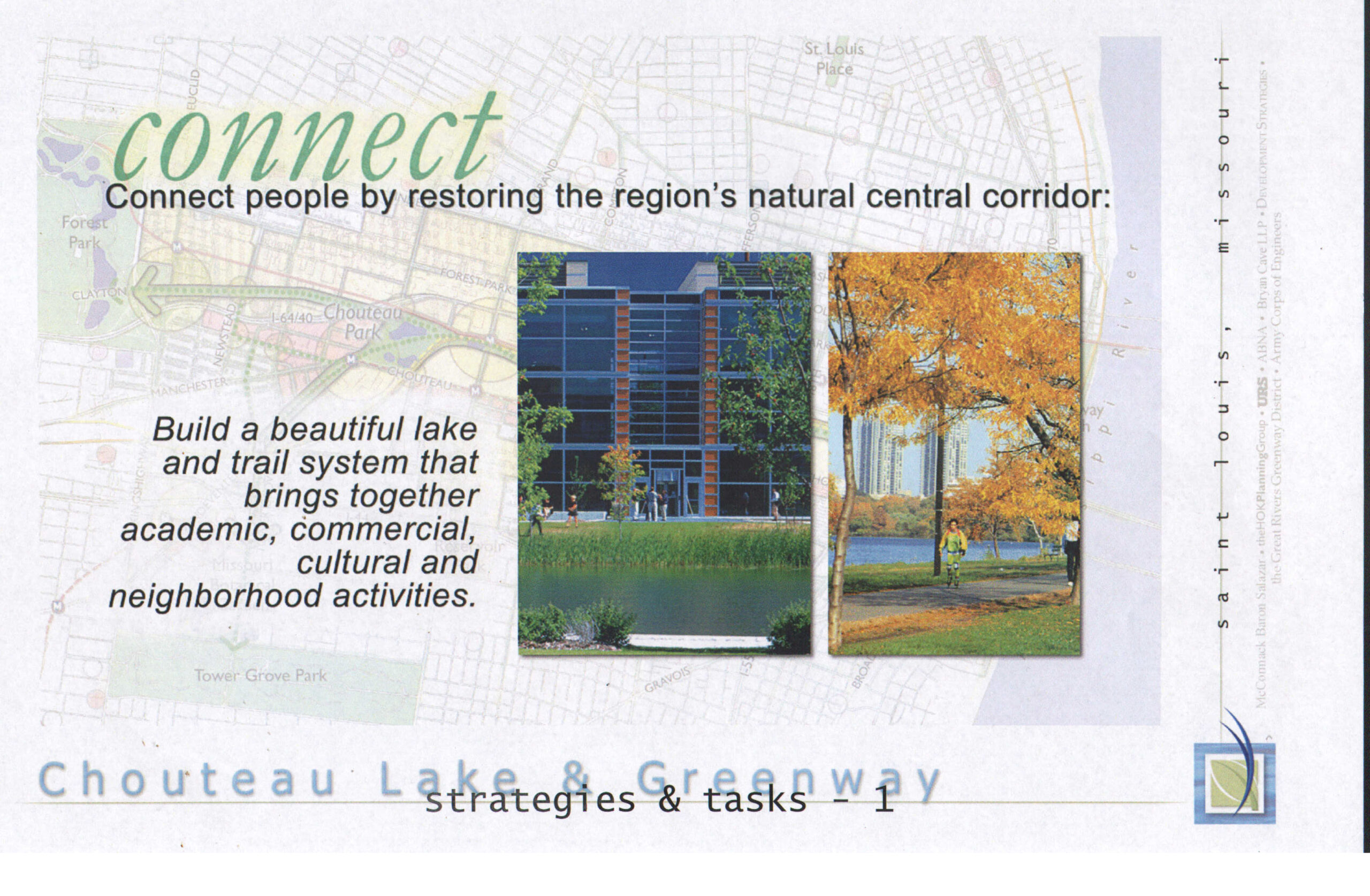

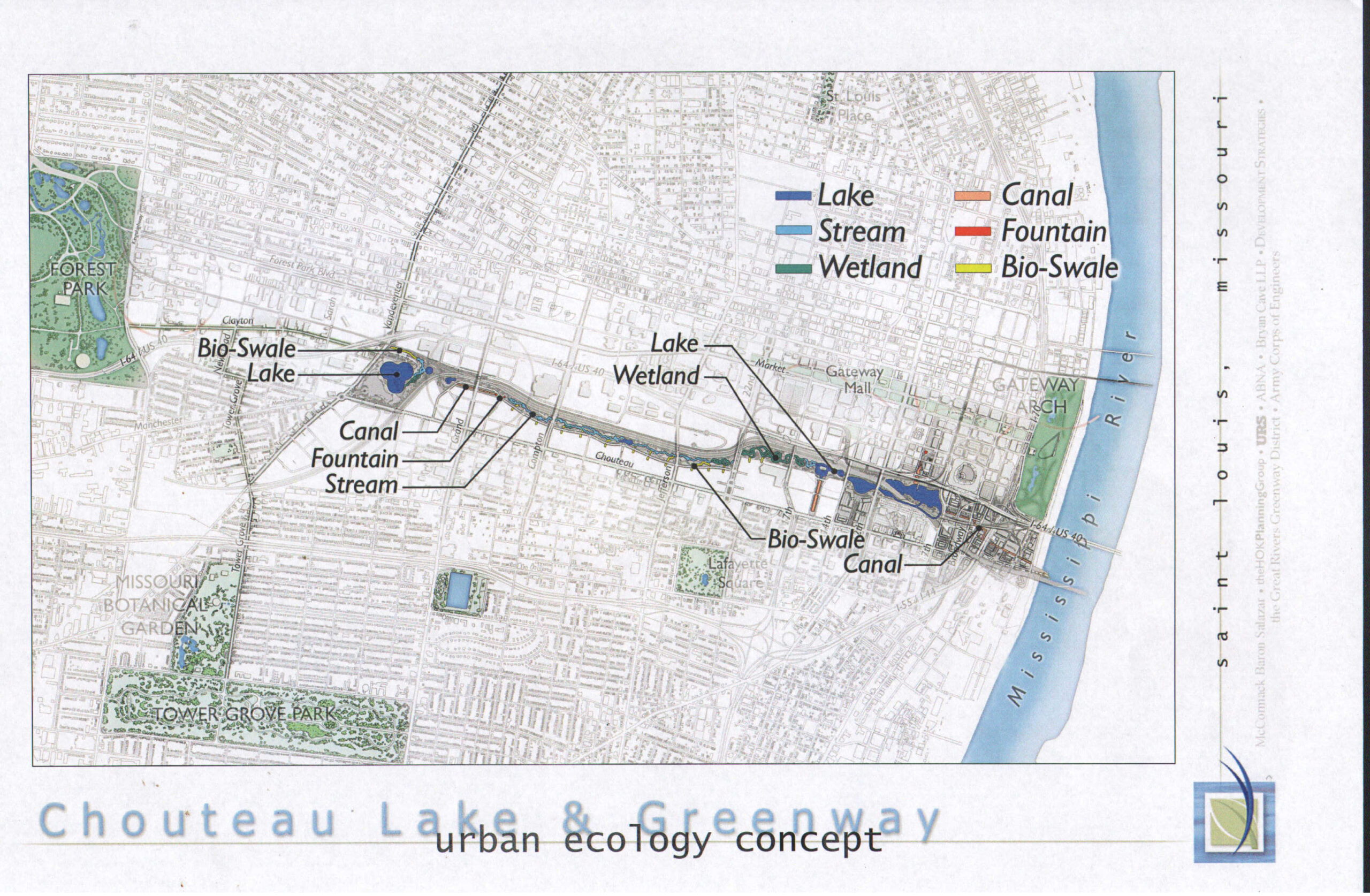

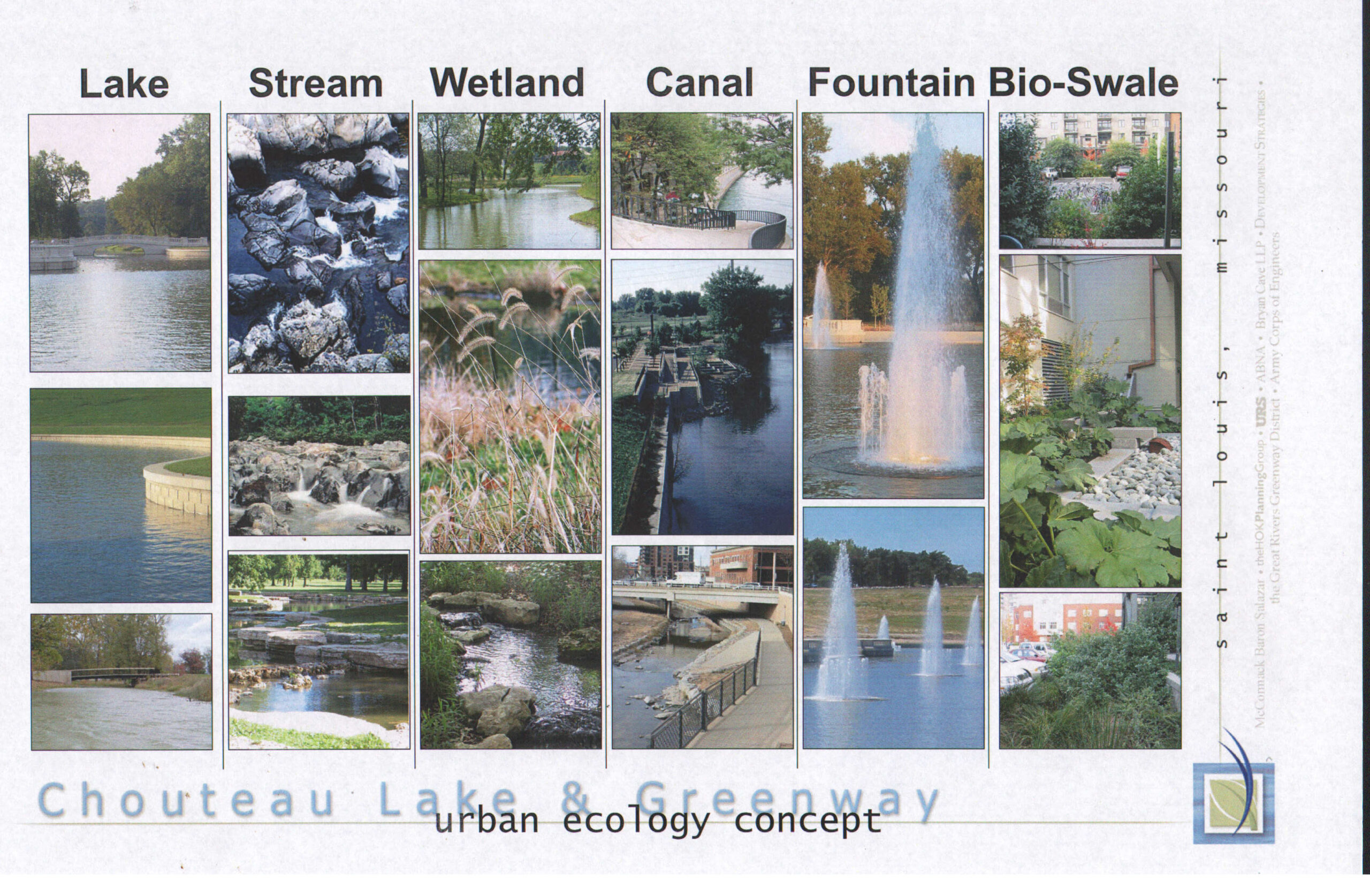

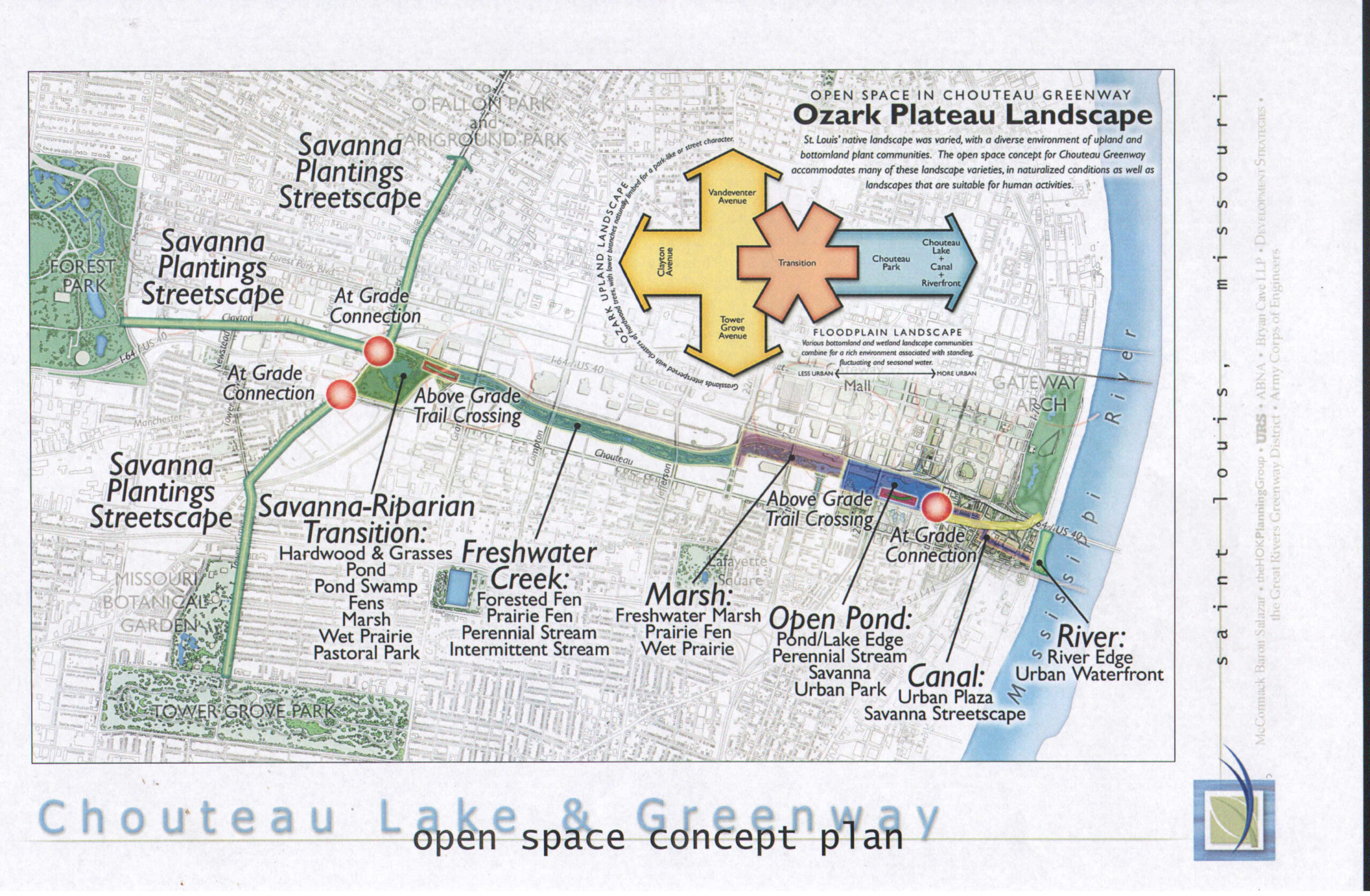

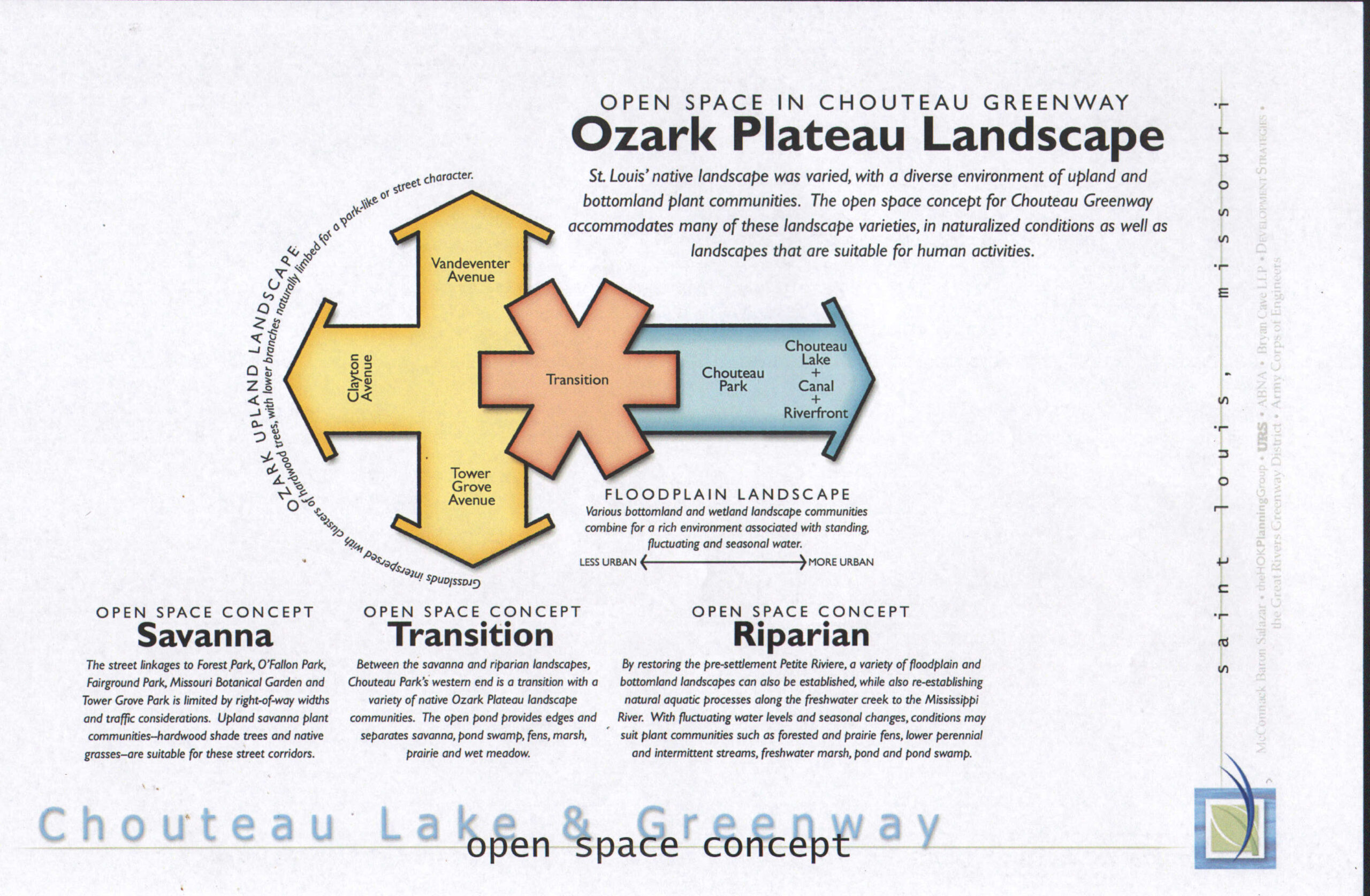

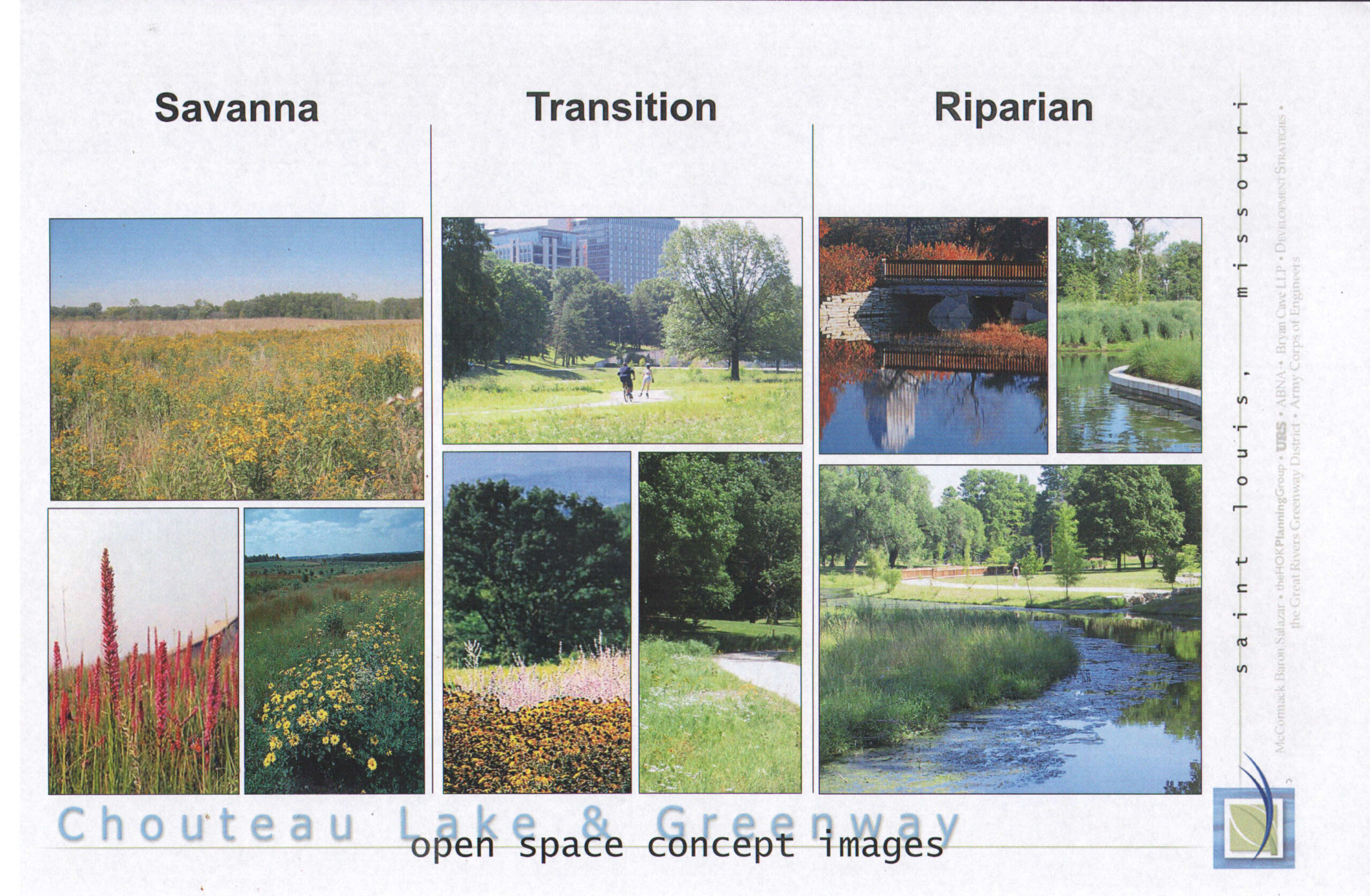

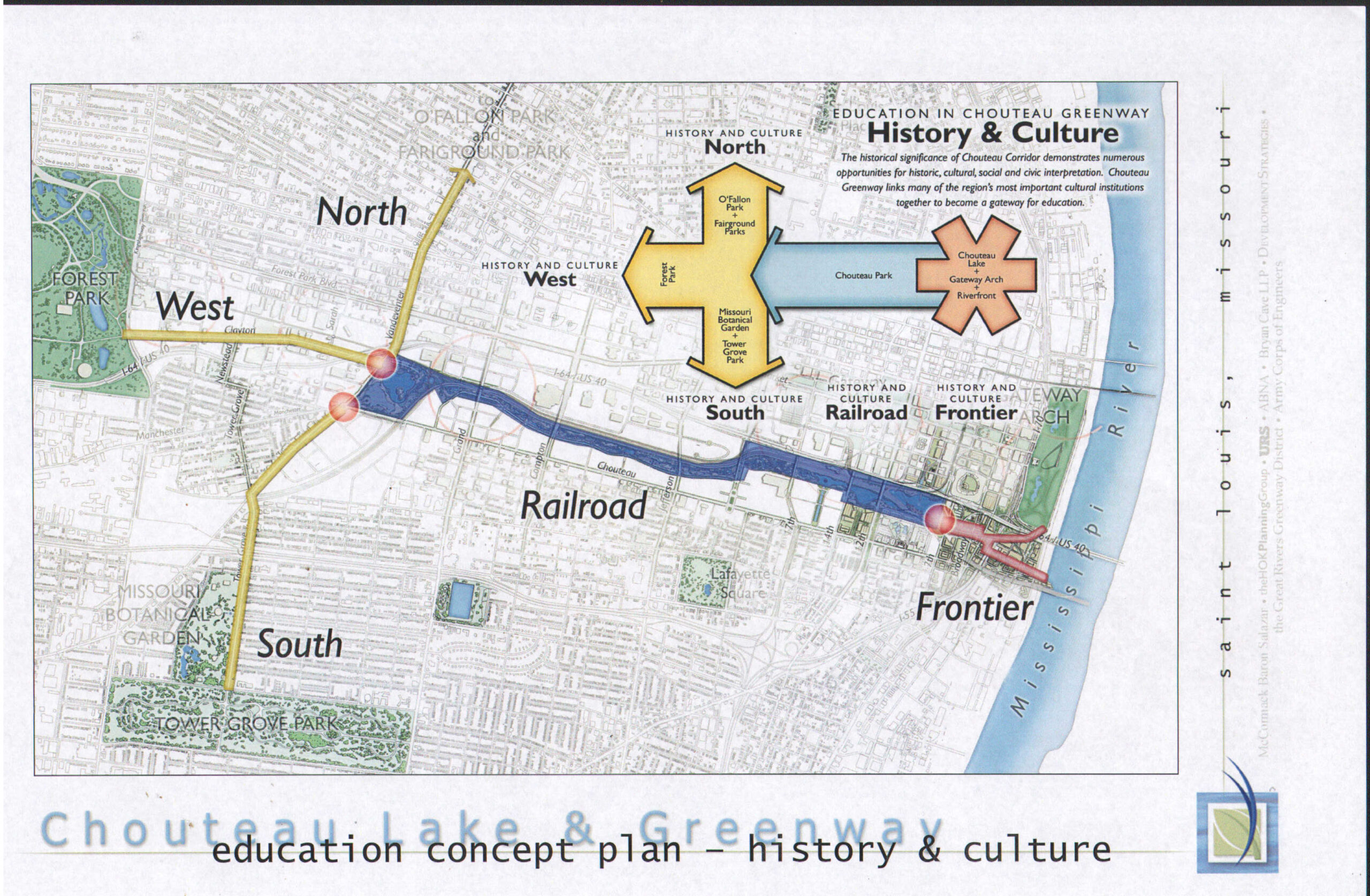

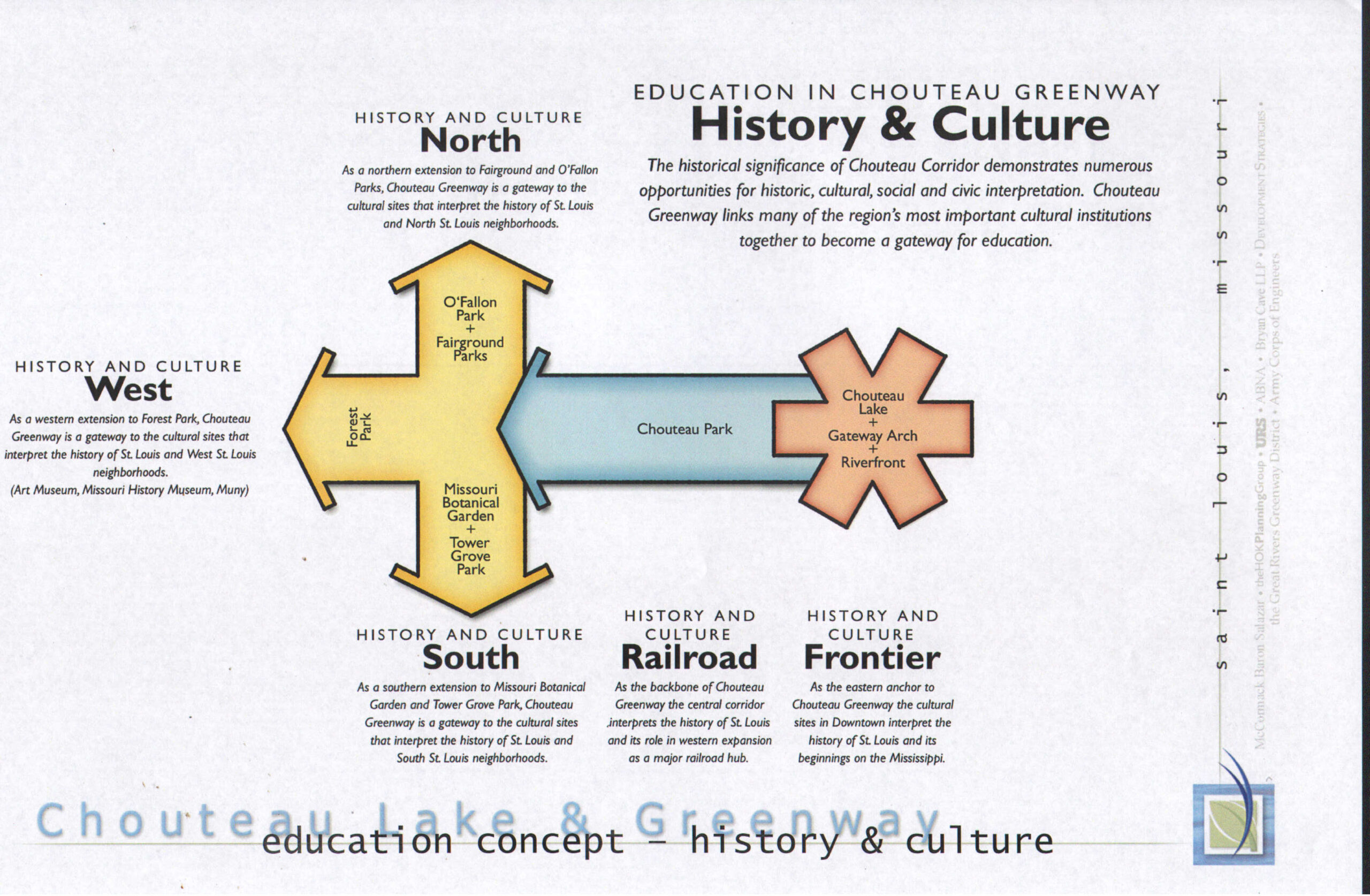

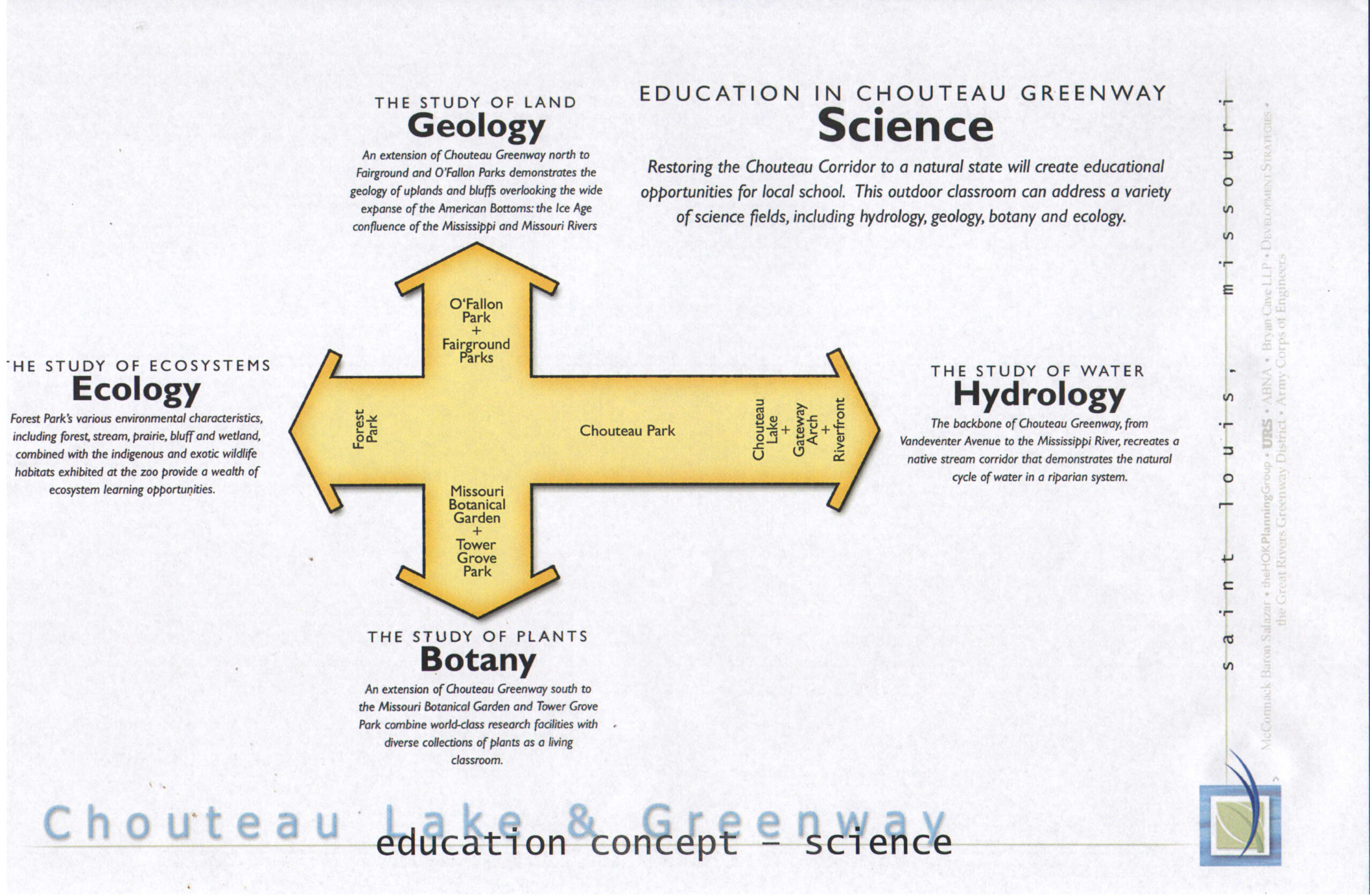

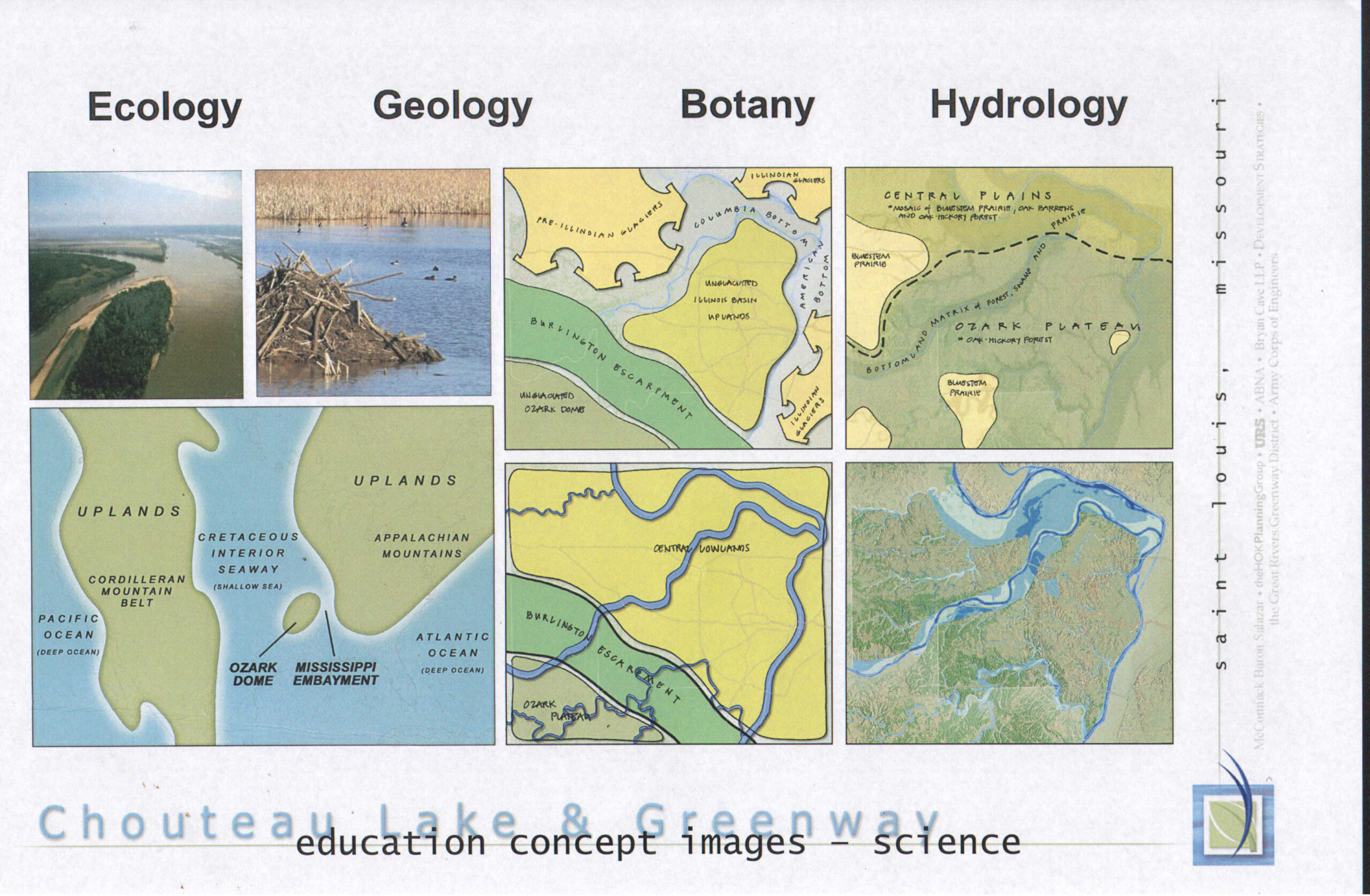

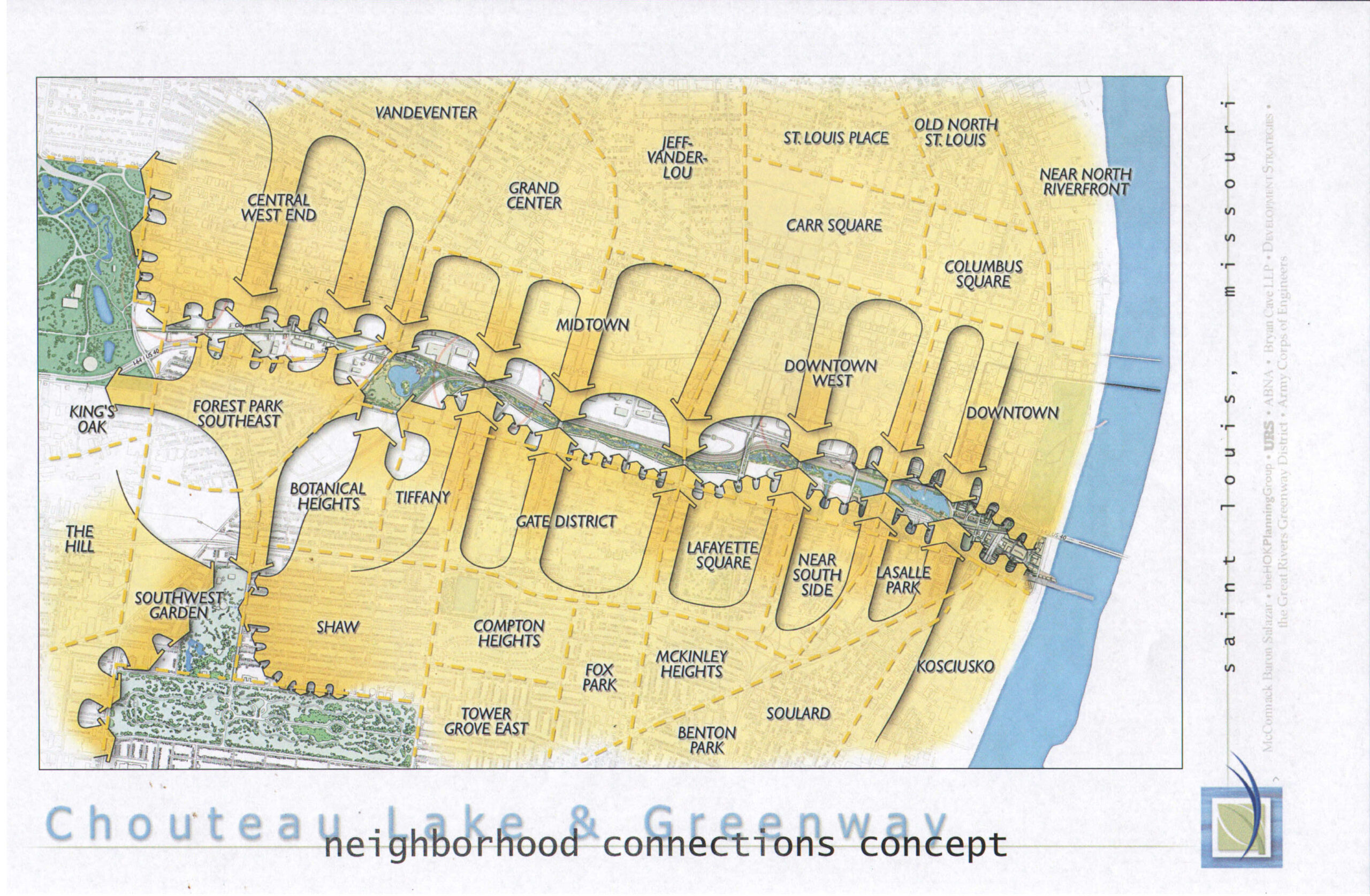

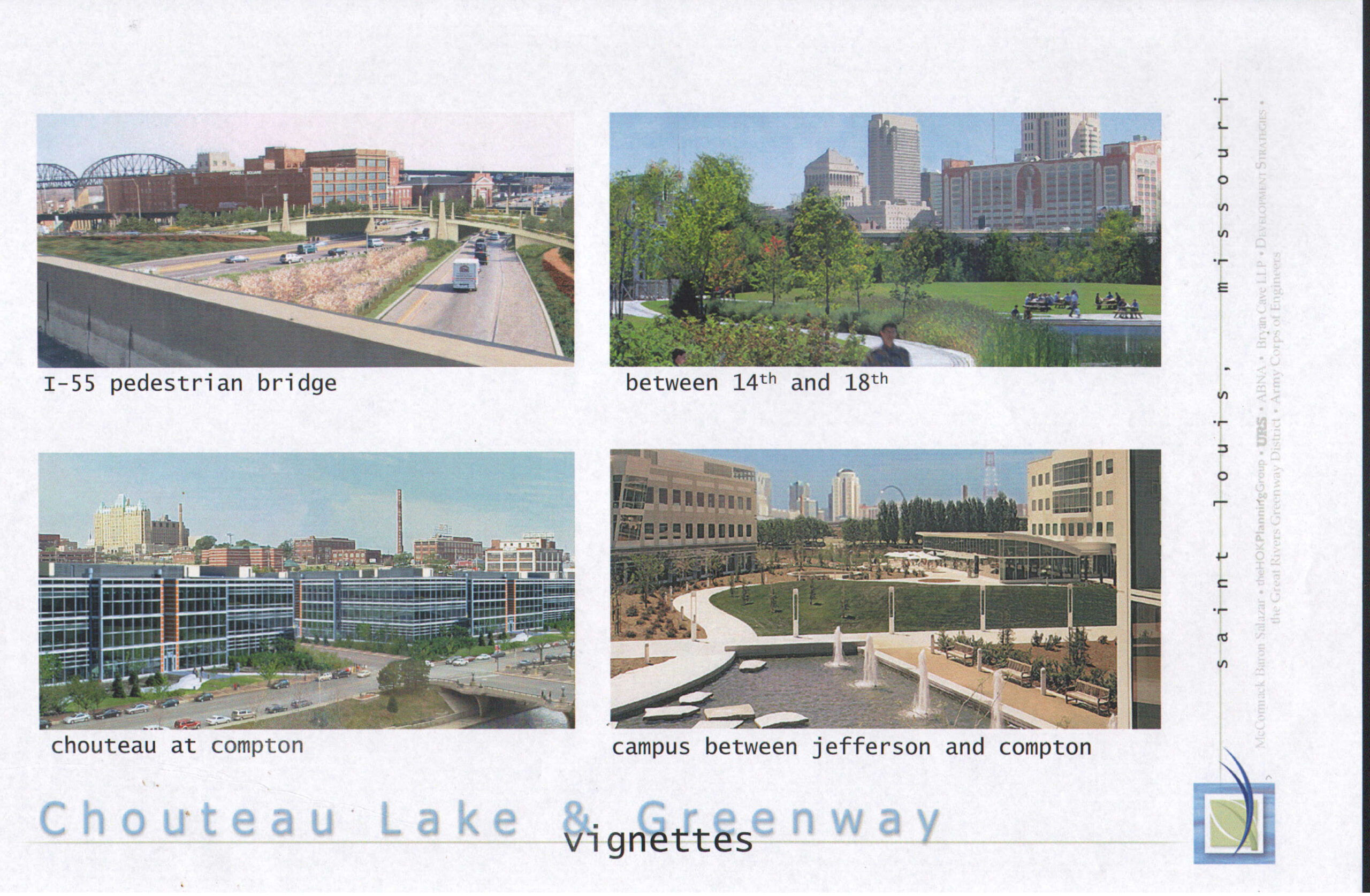

We had designed different areas of the trail to be ecosystems, and feature different kinds of grass and marsh. All kinds of wonderful landscapes, a whole natural environment through the center of the city. We had to meet with the city public works group because we had to work out a plan for reconstituting the lake periodically and how that was going to drain, and how we would keep the water supply there, and keep it fresh, and worked out a plan with them about how that would happen.

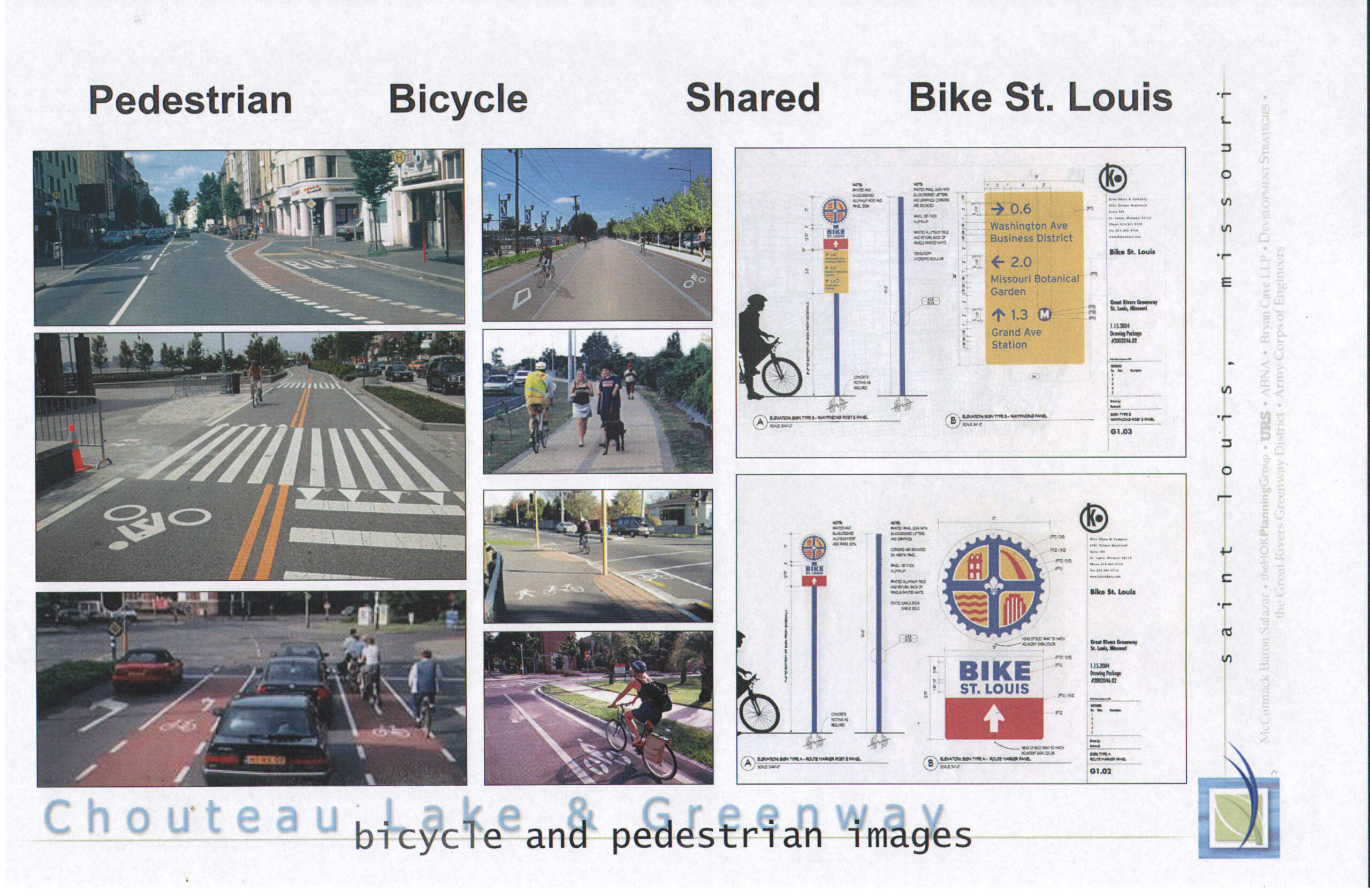

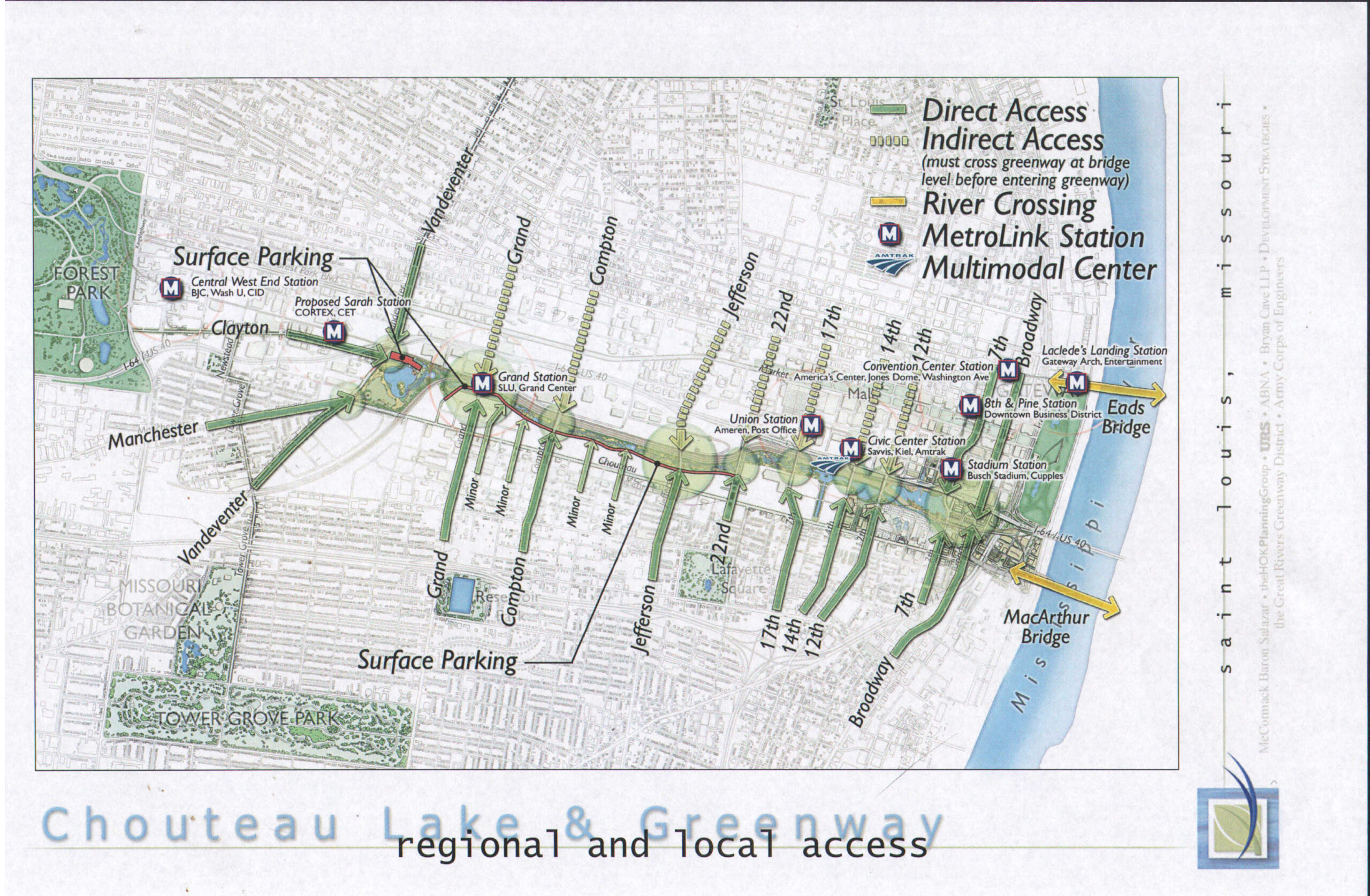

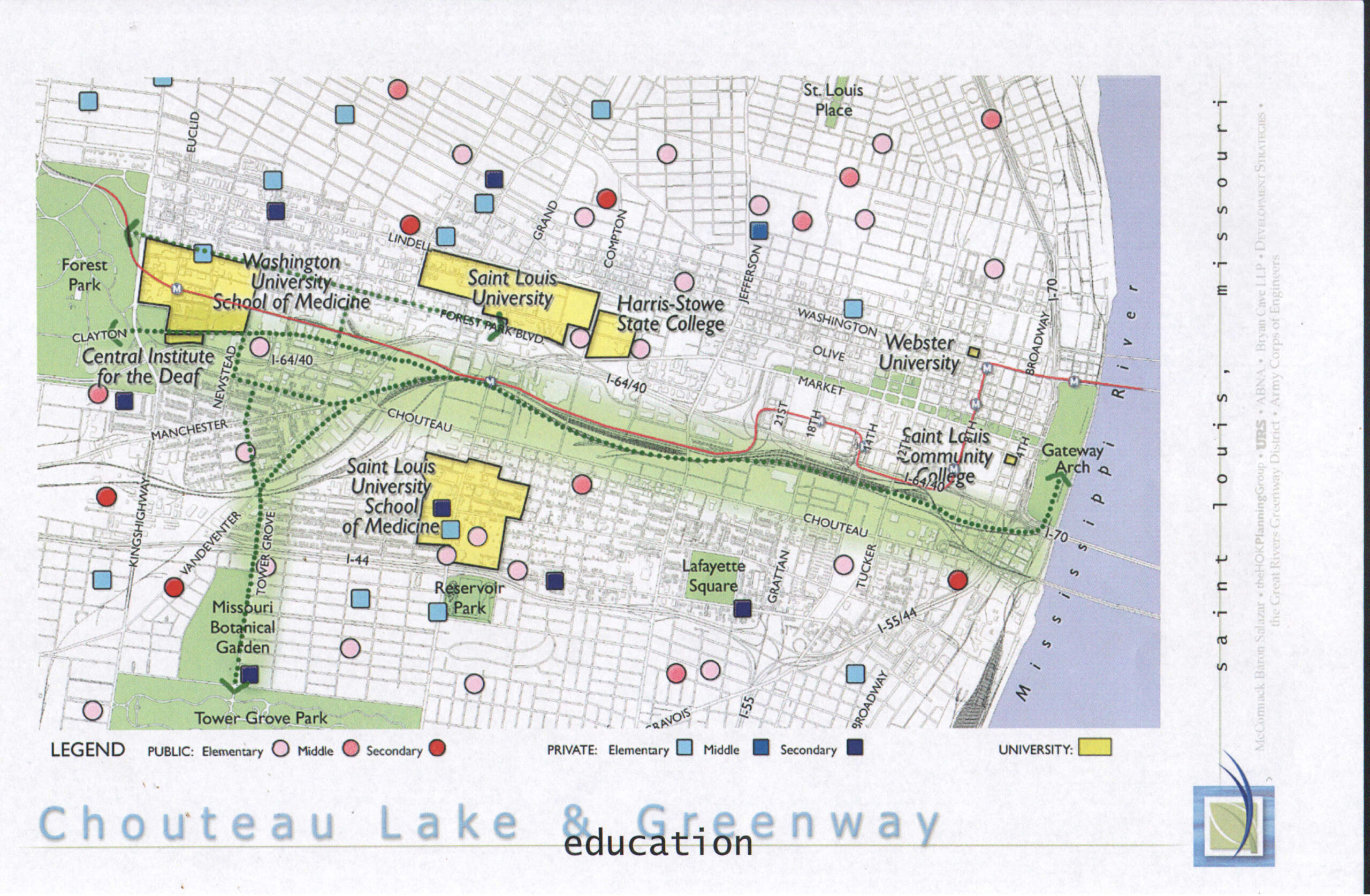

We had looked at all of these issues with transportation and the railroad and the way in which we could enhance Metro, which is running right through this area. And in terms of people biking to work–you got a stop at Cortex now and at Wash U campus and I mean still very, very sensible and could be a wonderful amenity for the city. Plus, you’ve got the ability now which didn’t exist then to get on Metro with your bike and come on in here at one of the stops–whether at the DeBaliviere or in the middle of the medical center or if you’re working at the BJC or SLU, and you’re riding your bike in in the morning or you’re in the city and you’re riding over, or you put your bike on the Metro at lunch time–you can just imagine the opportunities. It just made all the sense in the world in terms of doing something that was free of cars.

On the plan’s enduring potential

There still could be a lake built downtown. The water source, the one for the original lake, is still being pumped north under the (Central) library and across the river. And, I can imagine that people that are making housing decisions–the young professionals, small families, others–to buy a home close by the greenway or rent an apartment and get up in the morning and get out and get down in there and ride to work in Downtown, I mean imagine it–You wouldn’t have to drive. You wouldn’t have to park.

And I must say –today, if the CLG were now here with Buttigieg at the Department of Transportation, and with the ARPA funds that are available, putting the project together today would have been infinitely easier in terms of federal funding than it would have been back then. On the other side of it is that, this was in a period of time when they were still doing earmarks in the Senate, and Bond and Danforth would have been able to put our project into some kind of a funding bill with the philanthropy that I was absolutely convinced we could get from Ralston and from Ameren and from all the other business leaders and we could have put it together.

This was 23 years ago, but I can imagine there still would be interest. I mean I can’t speak for them, there’s new leadership with all these businesses and organizations. But I can imagine if this re-emerged and the city was willing to get involved in it as well – because they’re going to have to be the access point to the federal funding— that there would be interest.

But, you know, projects like this have to have some energy behind them, they have to have some leadership behind them, and very frankly, I just haven’t had the patience or the interests at this point in time, 23 years later to say –can we put the group back together, and can we just start over and go back to the mayor’s office and all of this.

I mean, if there were an interest then would McCormack Baron be willing to assist? Yeah, I think so, because at the end, I care about the city just like you do.