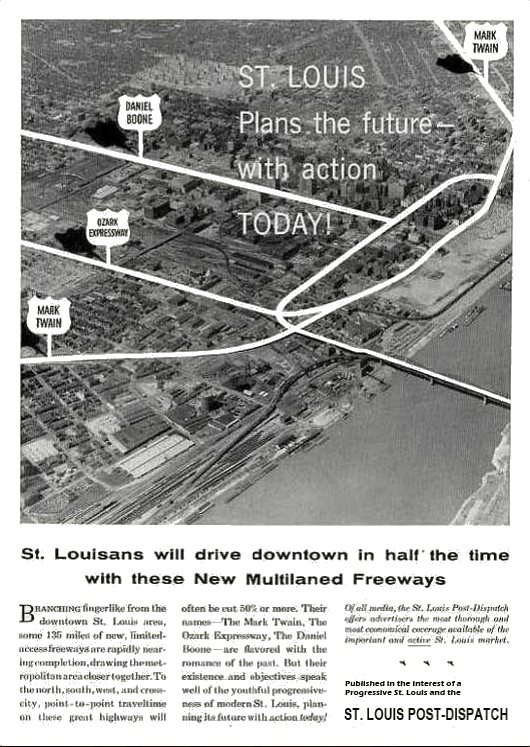

There was a time that the Interstate highway was a symbol of freedom. There was a time when the St. Louis Post-Dispatch could use urban highways to sell ads. “ST. LOUIS Plans the future – with action TODAY!” reads a piece of civic boosterism. “St. Louisans will drive downtown in half the time with these New Multilaned Freeways.”

This was a lie sold to cities and the monied white establishment. That overcrowding, the vacancy, the people who don’t look like you? In a progressive future you can fly right past it all. Left unsaid was who would arrive in half the time – not everyone of course, that would be impossible. The highways were only for those who could afford to move.

Quite apart from the original intent of a national highway system, which included economic development by quickly moving goods between distant cities, and national defense, urban highways were sold as a tool of segregation. They have proven to be wildly successful.

In St. Louis, according to the Urban Mobility Report, congestion has decreased while commuting times continue to increase. The region with the second most Interstate lane miles in the nation (only Kansas City, MO has more) has virtually built its way out of congestion. What this has produced, or in the most charitable interpretation, failed to prevent, is economic stagnation, deep racial segregation, and vast swaths of abandonment.

Fully 20% of the City of St. Louis is vacant, empty. As the regional population has shifted ever farther west, million square foot malls have failed – only more notable than the many many small businesses because of their monolithic stance, and stubbornness against redevelopment.

More than 30% of North St. Louis City residents lack access to a car. St. Louis has a regional transit agency beholden to suburban tax payers. Its most significant transportation plan on the boards? Faux Bus Rapid Transit on Interstate highways primarily serving far flung office parks, retail strips, and outlet malls.

The astounding fact that penetrates the local psyche is that since 1970, the three central counties of St. Louis City (its own county), St. Louis County, and proudly affluent St. Charles County, have grown by a combined 1%. The raw numbers: St. Louis City -302,942, St. Louis County +47,601, St. Charles County +267,531. The highways that left behind St. Louis City, are now leaving behind St. Louis County. Places like Ferguson, created by the Interstate, are being left behind.

In St. Louis City, Interstate highways removed approximately 1.7 square miles of urban land, rendering at least a like adjacent amount devoid of development. Considering this physical displacement in isolation, urban Interstates may have removed close to 30,000 residents from the city. Urban Renewal, to serve those new highways removed more than another square mile and 20,000 residents.

St. Louis City has one of the highest rates of poverty in the nation (29.3% in 2012). In 2010 when St. Charles County was recorded by the Census as having a poverty rate of 3.6%, one of the lowest in the nation, the county executive credited residents, stating that they avoid high-risk behavior. “Those who use drugs, drop out of school, and skirt the law are more likely to end up in poverty,” Ehlmann stated in his State of the County address.

Chesterfield, a municipality is western St. Louis County across the Missouri River from St. Charles County is home to what may be the largest strip mall in the nation. Next to this, two massive outlet malls were opened last year, all in a flood plain that was inundated in 1993, but made ready for development by a tax payer funded levee.

Yet, if you believe the mayor of Chesterfield, it is his community that is being slighted. In May, he threatened that Chesterfield would look at steps to keep more sales tax revenue, augmented by the new outlet malls, challenging the current system which requires a portion be pooled with the larger county of 90 municipalities (one being Ferguson) and more than 300,000 residents in unincorporated areas.

Today, the Missouri Department of Transportation Tweeted a photo of construction progress on the Boone Bridge, which carries I-64 across the Missouri River connecting St. Louis County and St. Charles County. The next Tweet? Celebrating the opening of ramps for Phase III of MO Route 364, a $569M three-phase project to build an additional Interstate-grade connection between St. Louis and St. Charles counties.

As Twitter documented all the actions across the nation shutting down Interstate highways in protest of the grand jury’s decision Monday, Los Angeles Times reporter (recently of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch) Tim Logan Tweeted: “Can’t tell if the highway shutdown protest thing says more about our nation’s systemic injustice or its automobile addiction.”

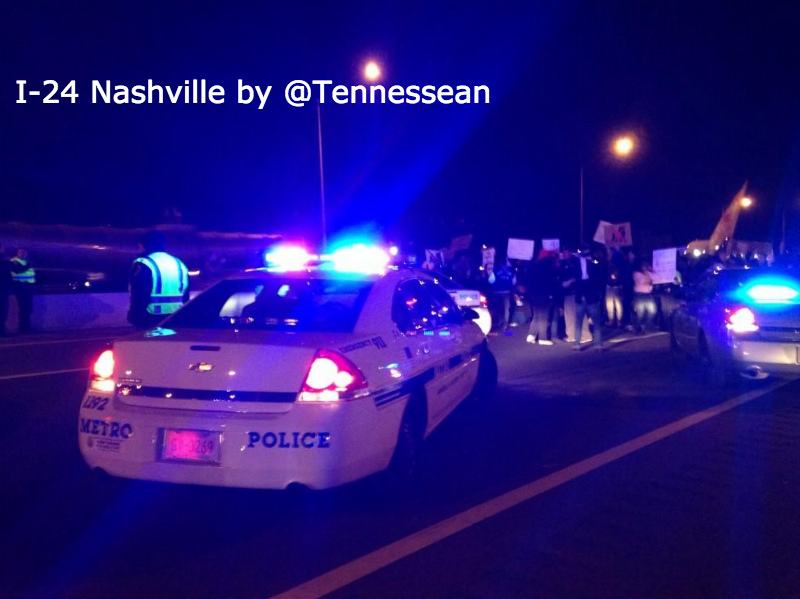

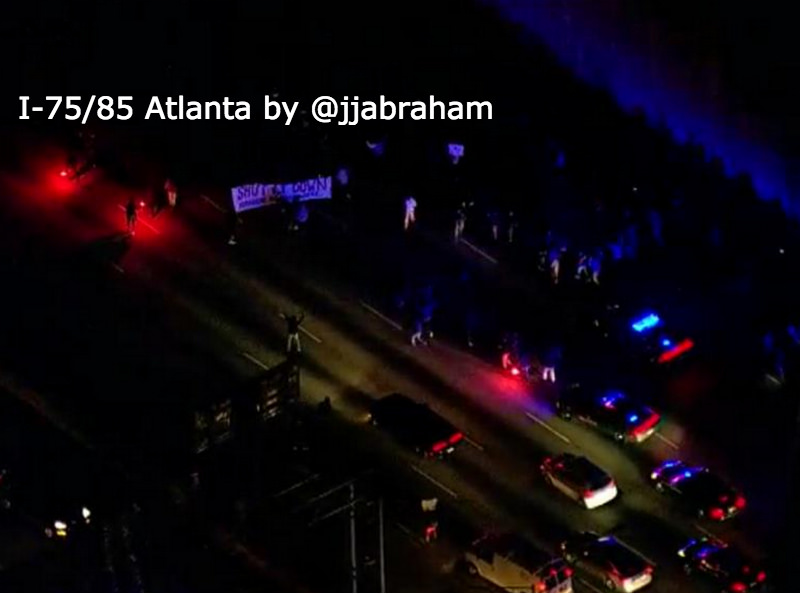

At last glance, protesters had closed portions of highways in Detroit, Atlanta, New York City, Cincinnati, Oakland, Nashville, Baltimore, Los Angeles, Washington D.C., and elsewhere.

Shutting down Interstates is a powerful and meaningful symbolic protest. It disrupts the thing which has materially enabled self-segregation. We have sacrificed our communities to allow people to pass through, fast. The symbolism of forcing a pause is powerful. Requiring that this mechanism, the one thing drivers are universally happy to claim ownership of in our urban areas, grind to a halt, is a powerful and meaningful statement.