In St. Louis County, Group A municipalities keep a portion of sales tax revenue and put the rest into a county-wide pool. Group B municipalities put all sales tax revenue into the county-wide pool and draw an allotment based on population. A pays into B, but B pays only into itself. In 2000, 290,000 people in St. Louis County lived in A Cities and 724,000 lived in B Cities.

In St. Louis County, Group A municipalities keep a portion of sales tax revenue and put the rest into a county-wide pool. Group B municipalities put all sales tax revenue into the county-wide pool and draw an allotment based on population. A pays into B, but B pays only into itself. In 2000, 290,000 people in St. Louis County lived in A Cities and 724,000 lived in B Cities.

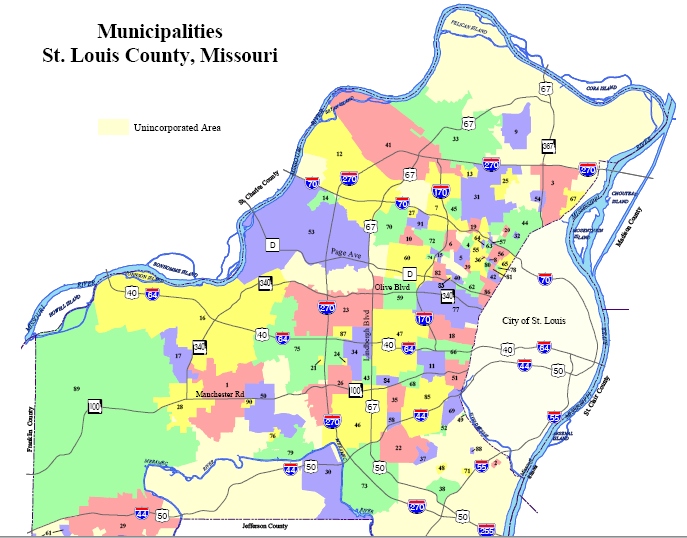

House Bill 534 being debated in Jefferson City seeks to change that system. It is proposed that beginning next year cities in Group A would not be required to share any revenue. Sales tax revenue generated in Clayton would stay in Clayton. Sales tax revenue in Maplewood would stay in Maplewood. Such a change would further balkanize the municipalities of St. Louis County.

At a time when serious people with serious ideas are working to create a more cohesive region that can better compete in our global economy, others are determined ignore economic reality and selfishly grab what they can by any means necessary. We should not be ushering in a system where regional assets are fought over by warring fiefdoms, the best thieves win, and the losers can’t afford police to patrol their empty storefronts.

More damaging, cities currently in Group B would be allowed to opt-out of the revenue pooling system and join the standalones in Group A. Large revenue generating municipalities such as Chesterfield and Maryland Heights would be expected to make such a move. Those cities remaining in Group B would then divide up a significantly smaller pool of money, leaving them less able to meet their needs.

The mayors of Fenton (Group A) and University City (Group B) have weighed in. Fenton supports the bill. University City opposes it.

Mayor Dennis Hancock of Fenton calls the current revenue pooling arrangement “a Robin Hood Scheme,” “Municipal Welfare,” and “Socialism.” As a Group A city, Fenton keeps 45% of its revenue and puts 55% into the pool. Mayor Hancock would like Fenton to keep 100% of its revenue, while simultaneously pointing out that 90% of the revenue generated in the Gravois Bluffs shopping center in Fenton comes from outside the county, mostly from Jefferson County. He has stated that he would like to retain this revenue so that it may be invested in the site of the former Chrysler Plant along with money from St. Louis County and the State of Missouri (also money from outside of Fenton).

Mayor Shelley Welsch of University City says the legislation would take $2 million out of her municipality’s budget, but that she opposes the bill because it would harm the St. Louis region. She believes, “people from throughout St. Louis County support commercial enterprises throughout the county, not only in their hometowns,” and that it should stay that way.

What is not being mentioned in the context of this debate, however, is the lesson we should have learned last November when Post-Dispatch reporter Tim Logan shined a light on our regional woes in his aptly named article, Area Stunts Growth by Feeding on Itself. Beside that title on the front page of the newspaper were two images, one of a shuttered Walmart in Town and Country and one of its replacement in Manchester. The article told the story of another Walmart in St. Ann, which moved up St. Charles Rock Road a short distance to be in Bridgeton. This tale of two Walmarts is one of public financing and what the mayor of Fenton might refer to as “Welfare.” One city offered more tax money than another. The store moved and the region lost money.

The municipalities of St. Louis Country have been very focused on increasing their tax revenue through the pursuit of retail and the poaching of jobs and shopping from neighboring municipalities instead of focusing on genuine job creation. Greater than 90 percent of TIF (a public financing tool) funded shopping centers are not new to St. Louis, but simply moved within the region. The investment of public dollars in a large shopping district, like Gravois Bluffs in Fenton, generates low-wage jobs and undermines nearby retail, such as slightly older stores in nearby Jefferson County.

This constant public investment in shifting our shopping around undermines any attempt to invest in meaningful job creation, like at Fenton’s Chrysler plant. Mr. Logan quotes Greg LeRoy of Good Jobs First as saying, “The whole idea of subsidized retail is nuts. Retail is what happens when people have disposable income. It's not an economic-development strategy." University of Missouri – St. Louis public policy professor Todd Swanstrom adds, “We’re subsidizing consumption. We don’t subsidize production.”

Returning to the proposed legislation in Jefferson City, let us consider what St. Louis County could look like when these retail developments which belong to the region can be made to exclusively benefit only the city in which they are physically located. Why did Maplewood (a Group A city) use eminent domain to destroy 153 houses and spend $16.3 million in public money to build a Walmart on Hanley Road? Let us consider the possibility that the residential municipalities, starved of sales tax revenue, will need to change their ways in order to survive under the proposed tax policy. The result will be more demolition, more TIF and more retail musical chairs.

In St. Louis County, Group A municipalities keep a portion of sales tax revenue and put the rest into a county-wide pool. Group B municipalities put all sales tax revenue into the county-wide pool and draw an allotment based on population. A pays into B, but B pays only into itself.

In St. Louis County, Group A municipalities keep a portion of sales tax revenue and put the rest into a county-wide pool. Group B municipalities put all sales tax revenue into the county-wide pool and draw an allotment based on population. A pays into B, but B pays only into itself.