Extreme Heat Belt (EHB) and Urban Heat Island(UHI)

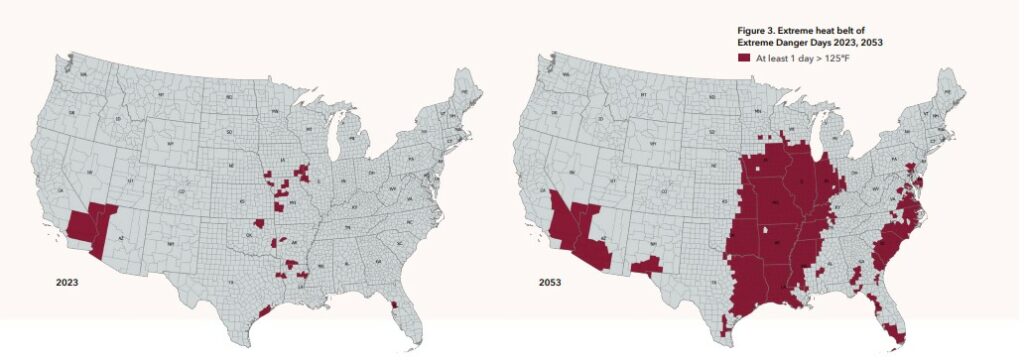

It doesn’t seem fair that the Midwest should be hit hardest by the heat of climate change, but that is apparently what is shaping up to happen. Last year the First Street Foundation released its 6th National Climate Risk Assessment. Among the dire predictions is an increase in extreme heat events throughout the Midwest over the next thirty years as temperatures rise across the continent and inland temperatures remain unmitigated by coastal weather patterns, a phenomenon cutting a broad path across the region from Houston to Chicago (encompassing all of Missouri) dubbed the “Extreme Heat Belt,” –a hulking mass of Midwestern counties that will experience at least one 125F heat index day per year.

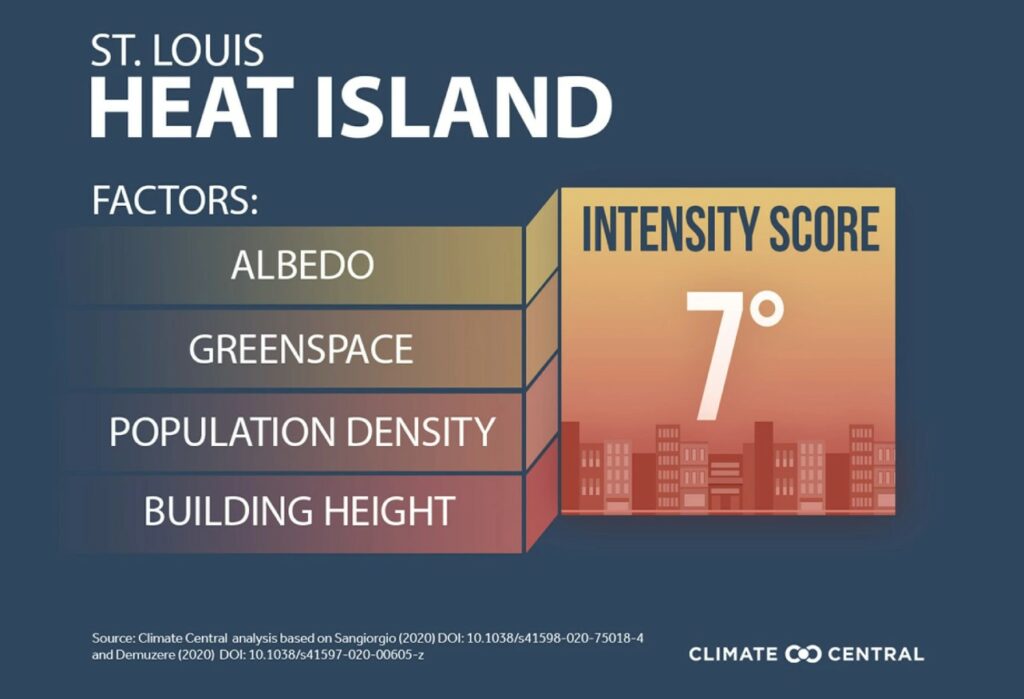

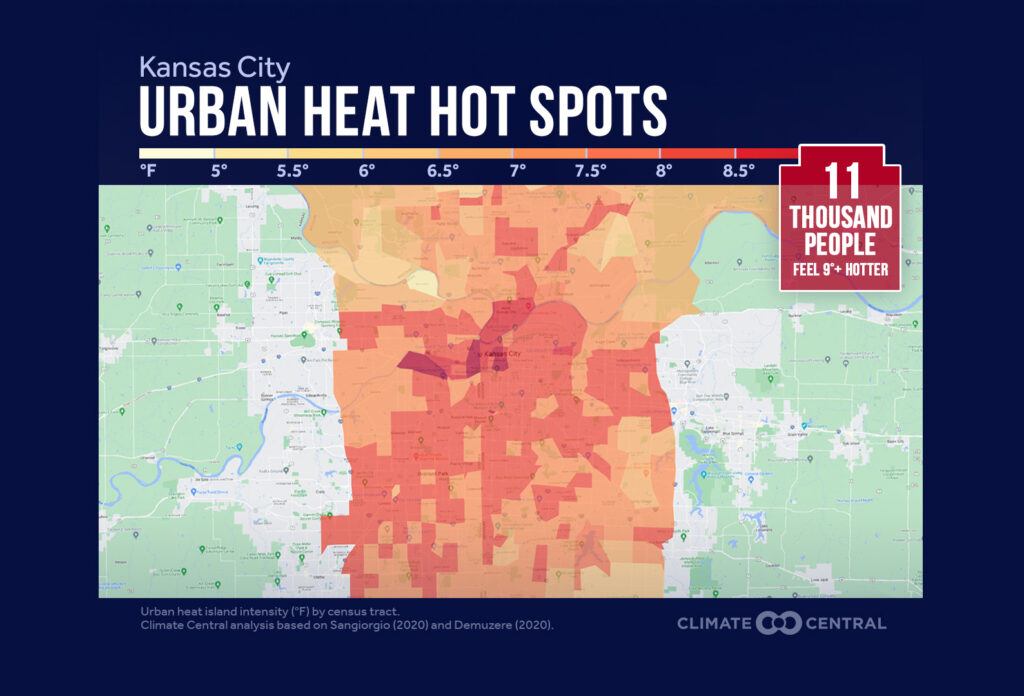

To make matters worse, the St. Louis region and particularly St. Louis City will experience temperatures on average 7 degrees warmer than surrounding areas due to the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI) as the sun’s rays are captured in dark impervious surfaces like roadways, rooftops, buildings, and parking lots throughout the area and radiate that heat into their surroundings.

That 7 degree UHI figure comes from Climate Central’s 2021 study as reported in this eye-opening article from St. Louis Public Radio. This past month, Climate Central released in-depth urban heat island figures for numerous American cities, but notably St. Louis was not included, as the city itself failed to monitor its own UHI data for the study. This data, on a city-level, is especially important because, of the two biggest factors that will increase heat events in the coming years (EHB and UHI), the one we can affect directly is UHI.

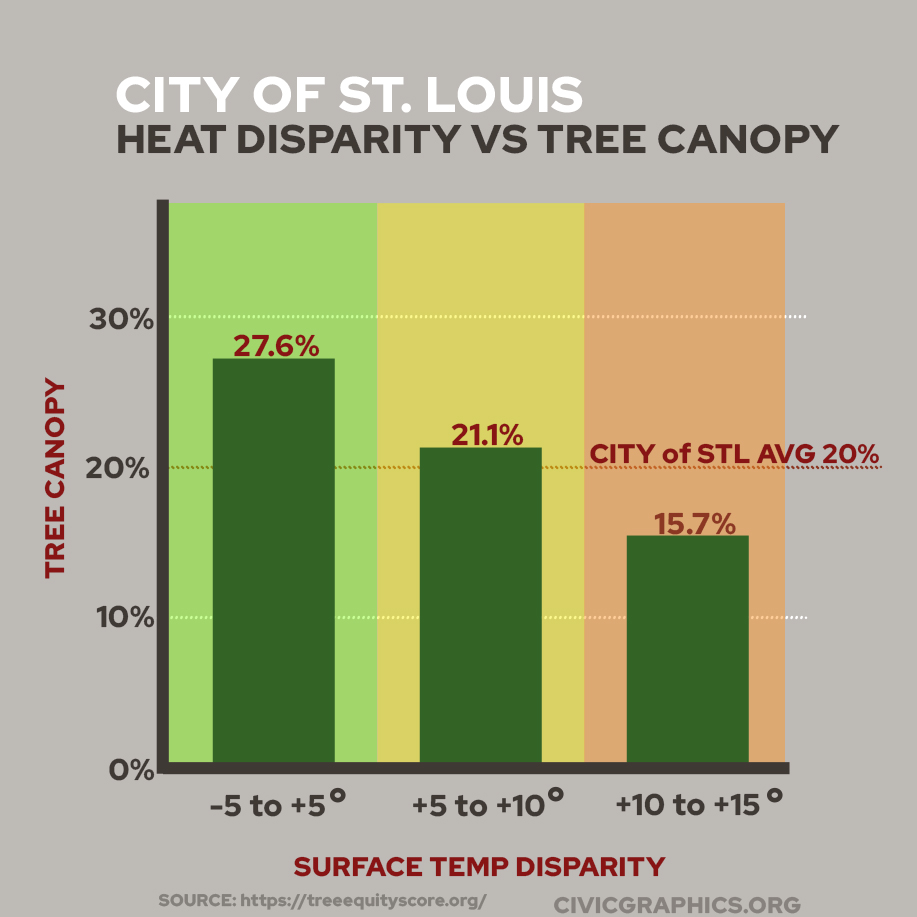

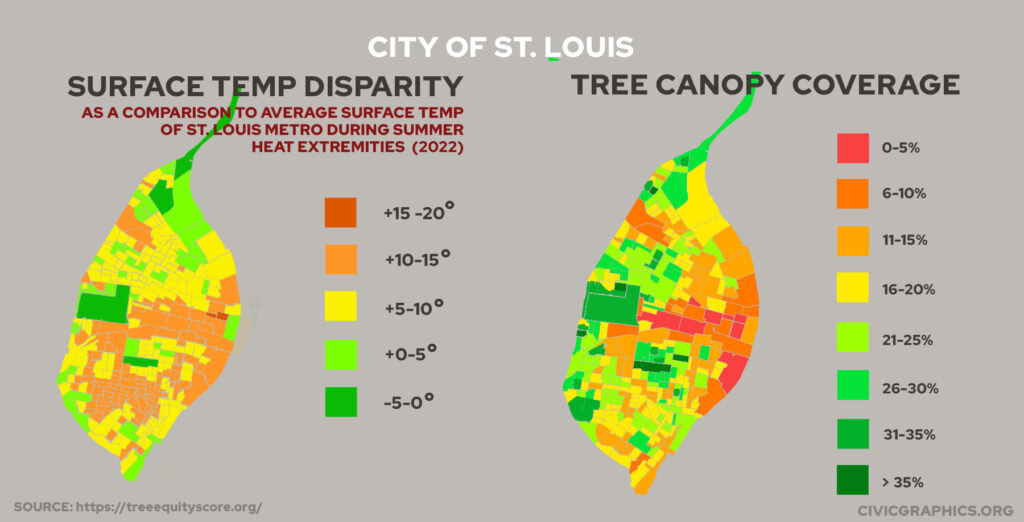

In the meantime, some similar data can be gathered from Tree Equity Score which released new data this past month focusing on tree canopy disparity across the US. The new data includes a new tool which shows Land Surface Temperature (LST) disparity on the census tract level across the country.

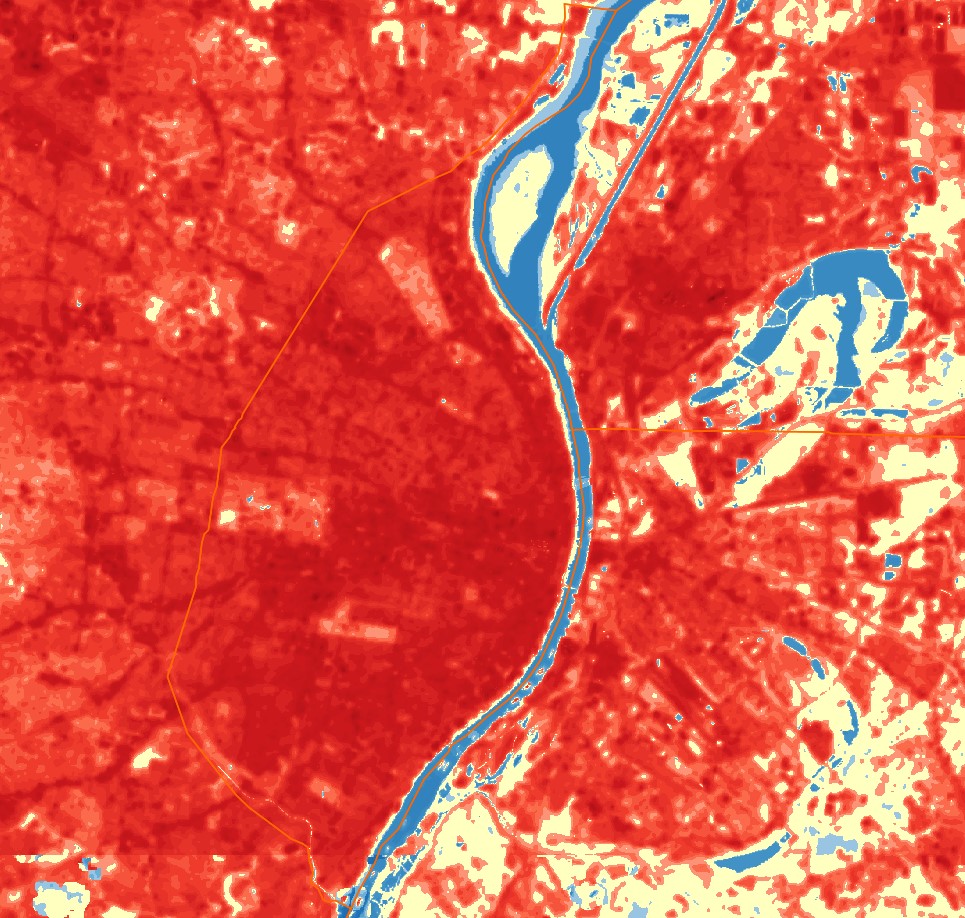

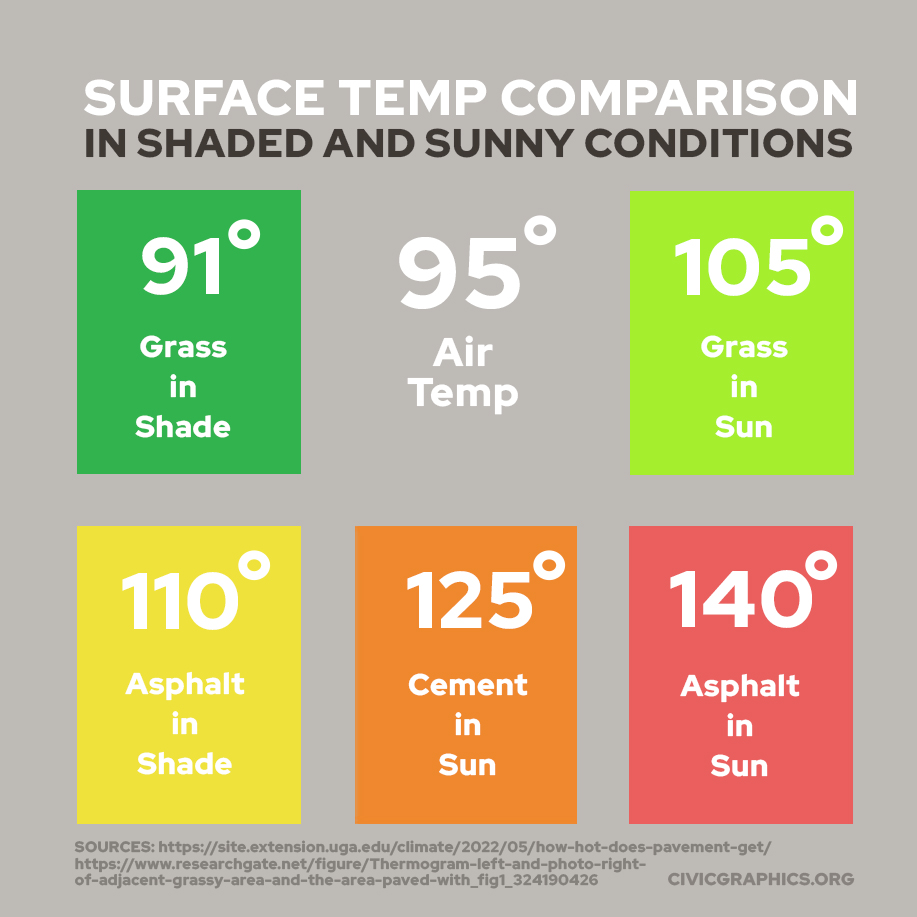

LST, which contributes to ambient air temperature and thus to UHI and deadly heat waves, can be mitigated, in part, by albedo–or the capacity of a surface to reflect light energy instead of absorbing it as heat. On our rooftops (especially in STL where so many of our roofs are flat) this can be achieved, in part, with a “cool roof”. On hot days, cool roofs can lower the surface temperature of a roof by up to -50F, which can lower ambient air temp nearby by as much as -3F. Cool roofs can also reduce cooling costs of a building by as much as 15%, which of course has downstream benefits for greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions. A quick look at satellite imagery (below) reveals perhaps a quarter of our flat roofs are high albedo white roofs, a quarter are very low albedo dark grey roofs, and the rest fall somewhere between–with cool roofs, predictably, being more prevalent in more affluent areas.

High albedo paints and materials are a no-brainer for our flat-roofs, but less-so for much of the urban environment, like streets and buildings, where blinding white reflective surfaces would be dangerous and/or intolerable. Nevertheless, some of our hottest cities have recently begun implementing higher albedo coatings on street pavement. It’s a strategy that STL may need to pursue in the years to come.

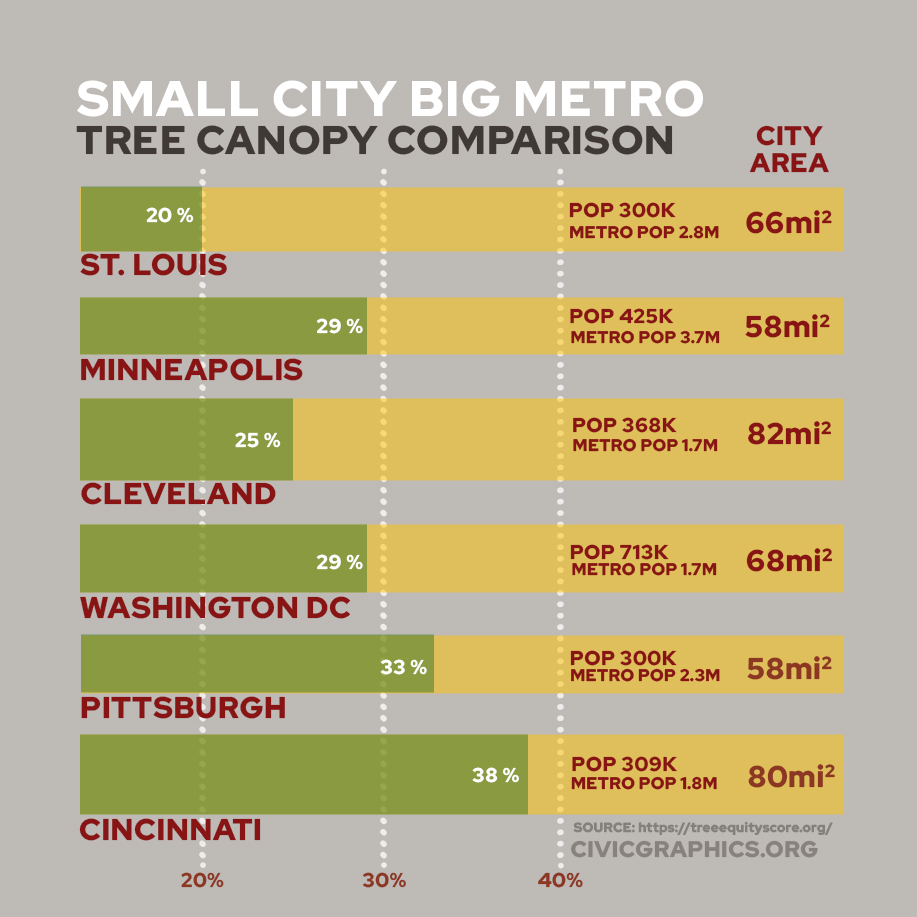

But it’s here, along our streets, that we need more trees. Unsurprisingly St. Louis’ tree canopy coverage (averaging around 20% coverage for the city proper by the new data) leaves a lot to be desired, especially in Downtown and the Central Corridor, and crucially, in Northside and Southside neighborhoods. With global temperatures rising, and with an inordinate effect upon the Midwest and the St. Louis region –we are on a heat island in a heat belt– St. Louis will need to stem the tide of heat exposure in the coming years to avoid expanding the crisis of heat related medical emergencies and deaths. To do this we’ll need more cool roofs, we’ll need less parking lots, and we’ll need a lot more trees.

Tree Triage

In STL A 10% difference in canopy(from tract to tract), can mean a 15 degree difference in LST at street level. Notably, Tower Grove Park which has a whopping 51% tree cover (by far the highest in the city) has the city’s lowest heat disparity index at -3.4 degrees below the metro area’s average. Likewise STL’s most treeless tracts, with just 3% cover, constitute its hottest places–like on the northern end of Downtown where the heat disparity index is +18.6F above the metro average.

A more direct look at STL’s LST data from iTree (left) reveals a web-work of overheated arterials and highways to the North, and vast expanses of even hotter developed areas in the central corridor and to the South. It goes without saying that much of this heat can be attributed to STL’s outsized car-oriented built environment. So many of STLs arterial streets are overwide stroads with excess driving capacity and parched, tree barren landscapes peppered with oversized parking lots. Like elsewhere in the city, these expanses, built or widened to accommodate a more populated and commuter oriented city of yesteryear need to be re-examined and right-sized for today’s needs and challenges–with street tree infrastructure being the priority. Within our neighborhoods the situation is often the same. Many blocks are entirely tree-barren. In the summer heat these streets feel like a gauntlet to be run, not a place to stop and enjoy. For residents, lack of tree cover increases cooling costs and energy demand on these blocks, and can rob homeowners of 3% to 15% added value to their home.

But planting and maintaining street trees has been easier said than done. St. Louis City’s Forestry Division, which is responsible for planting and maintaining trees in the public right-of-way, (like in your tree lawn/hellstrip) are understaffed and can hardly keep up with the demand to remove dead trees (including those ravaged by the emerald ash borer) to work on expanding the tree canopy. And, new street trees, which are often funded by STL’s problematic system of ward capital, are often distributed unevenly or not at all.

Nonprofits like St. Louis’ Forest ReLeaf have stepped in to help but are often finding it difficult to keep young trees alive. In their first few years young trees are especially vulnerable and have intense watering needs. Many are accidentally killed or harmed by mowers and trimmers, some are even vandalized or stolen after being planted. Since their beginning in 1993, Forest ReLeaf has planted ~240,000 trees in the region. Of those, since tracking planting in 2001, ~30k have been planted in the City of St. Louis where canopy is currently at 20%. Roughly the same number have been planted in St. Charles County where the canopy is at 25%, and a figure around 60k have been planted in St. Louis County, which already leads the region in tree canopy at 32%.

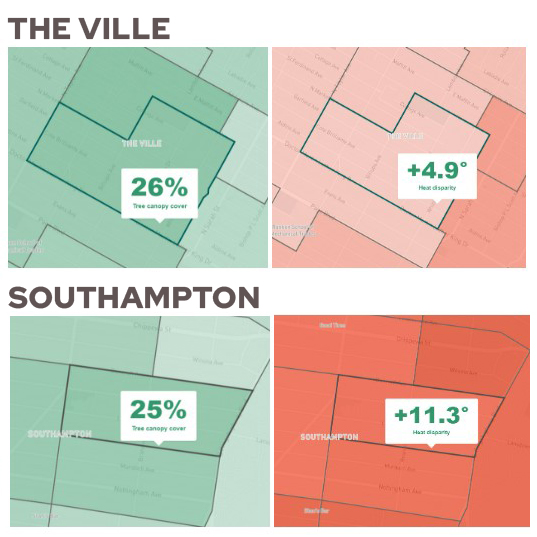

To complicate things, the data makes it clear that tree canopy isn’t always the defining factor. Take The Ville for example–by Tree Equity Score’s data a 26% tree canopy gets them a heat disparity of +4.9 degrees But take Kingshighway down into Southampton, and a similar tree canopy of 25% gets them a heat disparity of +11.3. The biggest difference between the remaining ¾ of these two areas is that the one is mostly buildings, the other is mostly grass.

Admittedly, if given the option on a hot day if I would want to be standing in the middle of a grassy field or under the shade of a roof, I would usually take the roof–but if we’re talking about reducing UHI, grass appears to be better than residential development (with its roofs, buildings, and parking pads). While the large empty green lawns of North City have been historically seen as a problem to be addressed, from the perspective of climate resilience, it is worth looking at them as an asset to be maintained and cultivated–especially given that a large percentage of these properties are banked by the Land Reutilization Authority (as seen in LRA’s available properties(blue) map of the Ville at right.) While residential redevelopment of North STL has long been the hope, that potential development should be weighed against the benefits of already re-greened spaces, and their possible further cultivation.

While this complicates the tree canopy story, it contains a lesson for our fully developed areas. Climate resilient surfaces exist on a spectrum where Tree-Covered-Grass > Sunny Grass >Shaded Asphalt. If you keep going down to the worst case, unsurprisingly, it’s a sunny asphalt parking lot. For fully developed areas, where there’s little room left for new canopy, this is where opportunity for the greatest change exists. Massive parking lots cover acres and acres of our developed areas. In some cases they are well used. In others, they stay almost entirely empty. In the latter case, they can’t be allowed to simply remain. Above a certain size, existing lot owners should be incentivized to regreen these spaces, and future developers should be mandated to provide a certain amount of greenspace per square foot of lot. Re-greening paved surfaces is difficult, expensive, and no doubt politically, and economically tricky–which is precisely why it’s important to protect green spaces where we already find them.

On private commercial or residential property, whether fully developed or post-developed (we won’t get far here referring to places as “underdeveloped”), we can incentivize the growth of trees with tax incentives and grants. MSD’s Rainscaping Grants Program, is a good example of how something like this might work (Did I mention trees also capture tons of stormwater?) Where gaps exist in maintaining young trees on public land or in the public right-of-way, community members armed with minimal training and organized by an app might be deployed to water and monitor trees, making a little gig-economy cash for every tree cared for. The city is already part-way there with this cool Street Tree Inventory Map maintained by the Forestry Division.

30% in 30 Years

At 20% canopy coverage, St. Louis City ranks low compared to many other major cities in the Midwest, but like all statistics, this is also complicated by the city/county split. Of cities close to our size to the east, DC has 29% and Pittsburgh 33% Of Midwestern post-industrial cities near our land area and relatively comparable population, Cleveland has 25%, Minneapolis has 29%, and Cincinnati (closest to us in size and pop but not necessarily in geography) has a whopping 38%. If we were to endeavor to catch up with Cleveland’s 25% canopy, their data suggests we’ll need to add (not just plant, but add) over 140,000 trees (cumulatively on private and public property) to our canopy. Double that if we want to reach 30%–280,000 trees, or nearly one new tree for just about every resident of the City of St. Louis.

30% tree canopy in STL? It’s not impossible(many cities have Million Tree Initiatives underway), and we certainly have the land to do it, but trees don’t grow overnight–many take 15-30 years to mature. If we want a mature canopy of 30% coverage in 2053 we need to be planning and planting those trees now. We should be bulking up our Forestry capacity, empowering and assisting groups like Forest ReLeaf, who have been planting trees and educating on reforestation for decades, to expand their work greatly and focus it where it is needed most in the urban core.

We will also need to look for opportunities to expand tree nurseries throughout the city like Forest ReLeaf’s planned City Tree Farm (planned for 2024) but on a bigger scale–opportunities like the one Reenvisioning the Workhouse, which is seemingly situated well to pump water for trees from the Mississippi. Others have suggested the former Pruitt-Igoe site (if it could only be wrangled back from its current owners), which could be a meaningful and redemptive reuse of a site with such an historic and infamous past. From a vacant land perspective, opportunities abound.

If we can reforest and regreen our city alongside cooling roofs (and maybe streets and parking lots?), and collect the important data we need to succeed, we may be able to cool our urban heat islands in a meaningful way. If EHB heat predictions are correct, this will literally be a life-saver. Even if somehow they’re not, we’d have a far greener, more beautiful, and more hospitable city–something we’d be unlikely to regret.