Another person has died while walking* or biking on St. Louis streets. On September 6th, another person was struck and killed by a driver while biking in St. Louis. In this latest crash, a driver illegally entered the painted bike lane to pass another vehicle along Grand Ave near Magnolia Street, hitting and killing someone in the process.

This death was the 6th fatality of someone walking and biking since July 1st, an unprecedented amount of fatalities in that time span. Of those six fatal crashes, four are known to be hit-and-run crashes. The combination of dangerous driver behavior (running red lights, speeding, etc) and lack of safe walking and biking infrastructure is continuing to put St. Louisans’ in danger, and the issue of traffic violence should be a top issue for the City.

Part 1 of the Moving Forward Series highlighted how street design and infrastructure (which prioritizes people who walk, bike, and use transit) can reduce traffic violence in the City of St. Louis. Part 2 will focus on utilizing traffic enforcement strategies to reduce traffic crashes and dangerous driver behaviors like speeding and running stop signs.

Writers Note: Before we get into the article, I want to be clear about one thing. The solutions and strategies I propose should not be implemented independently. For our region to reach zero traffic fatalities we need to be adopting proactive transportation policies programs and constructing infrastructure simultaneously. Infrastructure that promotes safe walking and biking is not the sole solution to reach zero fatalities. We need policies and systems that hold drivers accountable for their dangerous behaviors, education programs that teach safe driving practices, and funding systems that allow these programs to be implemented quickly.

Police & Traffic Enforcement

For decades, police departments have been responsible for several aspects of traffic-related issues. Officers are typically the first to arrive at traffic crashes and mainly responsible for citing traffic violations like speeding violations to broken tail lights and everything in between. Traffic stops and violations are often the most common interaction people have with police officers. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 42% of face-to-face interaction people in the United States had with law enforcement was for a traffic stop.

Traditional traffic stops and ticketing by police officers has often been used as a way to decrease dangerous driving behavior and to reduce crashes. Unfortunately, a large nationwide study proved no association between traffic stops by police officers and motor vehicle crashes and deaths.

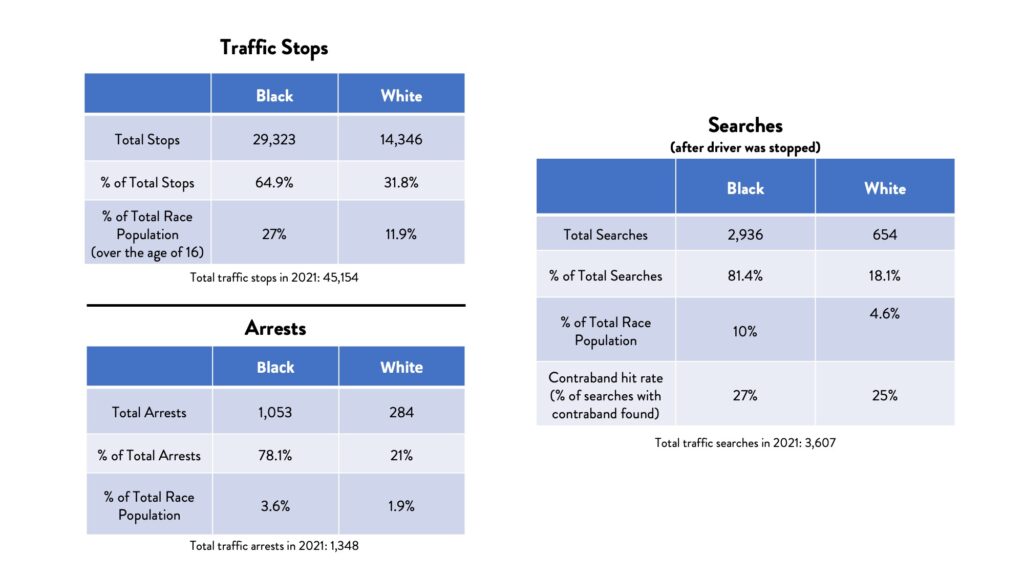

Another downfall of traditional police officer enforcement for traffic violations is the noted racial bias and inequitable enforcement. Nationwide, with thorough support from an initiative called the Stanford Open Policing Project, Black drivers are more likely to be stopped, searched, arrested, and killed in traffic stops than White drivers. In the City of St. Louis, those disparities are also prevalent.

In St. Louis City, twice as many Black drivers were pulled over by law enforcement than White drivers

2021 Missouri Attorney General Vehicle Stop Report

In 2021, 45,000 traffic stops were performed by the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. Of those 45,000 stops, 65% were of Black drivers and 32% were White drivers, while Black St. Louisans’ account for only 43% of the total City population (over the age of 16). Black drivers were also searched at a higher rate than White drivers. After being stopped,10% of Black drivers were searched by law enforcement, compared to 4.5% of White drivers.

Source: 2021 Missouri Attorney General’s Annual Vehicle Stop Report

Relying on traditional police stops and law enforcement is not working to 1) reduce crashes and dangerous driving and 2) decrease racial bias in traffic stops. In recent years, technology and other enforcement methods have shown potential to reduce traffic crashes and reduce racial bias in traffic enforcement.

Automated Enforcement

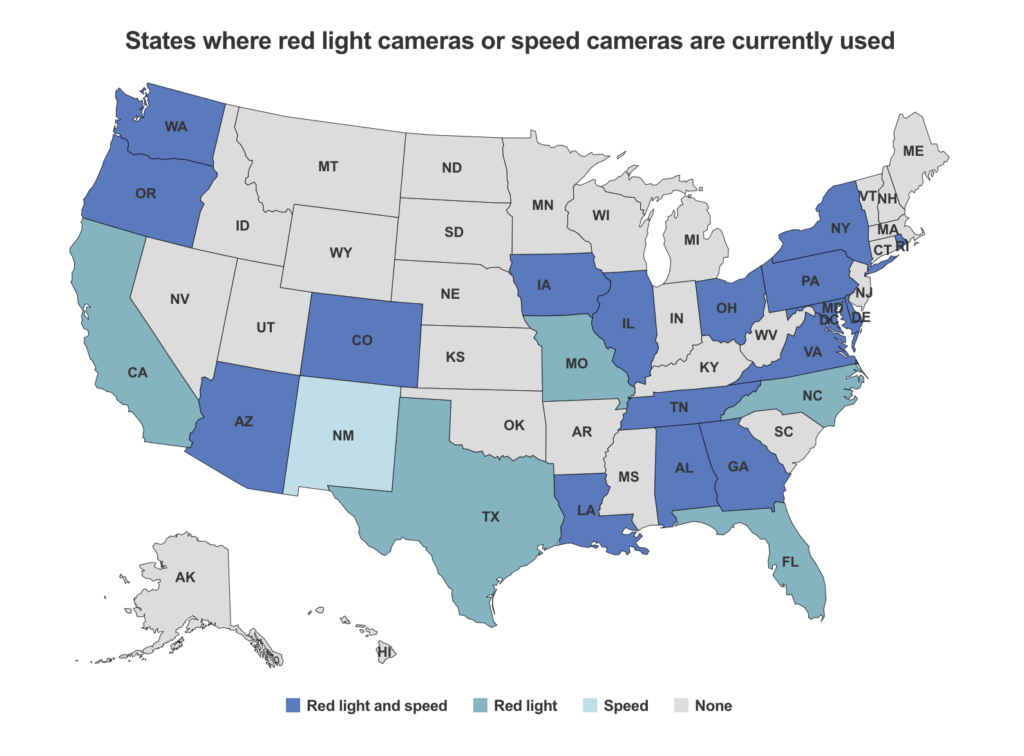

Automated enforcement is often used as a solution to reduce traffic crashes and dangerous driving behavior without performing traditional traffic stops. Automated enforcement takes many different forms in different cities and states. Some cities implement fixed cameras that sit on stop lights, others have portable cameras and vans that can be placed along high speed, high crash corridors. The technology is used to enforce safe speeds and compliance with red lights. Red light camera enforcement is used in around 350 communities across 22 states, and speed cameras are used in more than 150 cities in 16 states.

St. Louis is familiar with automated enforcement technology, specifically utilizing red light cameras for a period of time. The legality citations from the red light camera technology was called into question three separate times by elected officials and lawyers. Finally in 2015, the use of red light cameras was deemed unconstitutional by the Missouri Supreme Court, terminating the use of the cameras in the City of St. Louis.

In many states and communities, red light and speed cameras automatically record vehicles going through traffic signals and speed zones. If a driver illegally runs a red light or goes over a certain speed, the camera will capture the license plate information and trained police officers or authorized civilian employees to review every picture or video clip to verify vehicle information and ensure the vehicle is in violation, then issue a citation to the owner of that vehicle. As with all traffic violations, there is an option for appeal of these violations, in the instance that the vehicle was stolen or other circumstances (IIHS).

It is important to remember that automated enforcement should be used as a tool for public safety, not revenue generation. While a fine is collected, the funds generated from automated enforcement should be redistributed back into a fund that supports building out safe streets. The goal of this technology is to reduce crashes and dangerous driver behavior, and in many cities automated enforcement has reduced these behaviors.

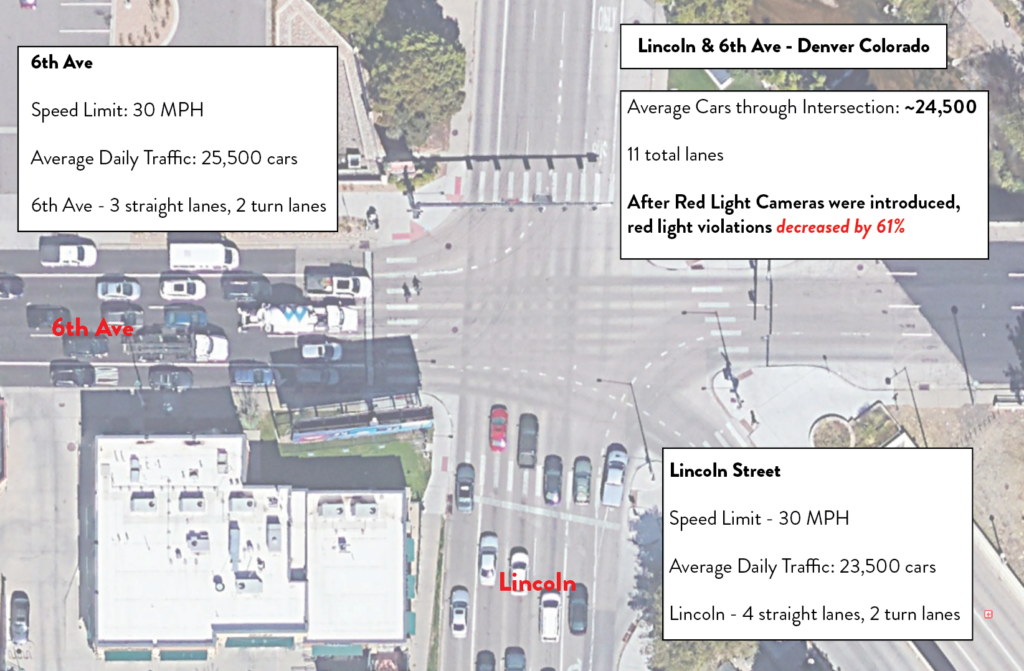

Red light studies in California and Virginia found that red light violations decreased by 40% after red light cameras were introduced, and the effect of the cameras even carried over to nearby intersections that weren’t equipped with automated enforcement technology. In Denver, they implemented red light cameras at four major intersections, and all four intersections saw decreases in red light running violations, with two intersections decreasing red light running by over 50%.

Speeding and crash rates also decreased in several cities due to automated enforcement. The Denver program, which uses a marked van to enforce speeding violations saw a 7.6% decrease in traffic speeds in one week after the van was placed on a major arterial. In Chicago, researchers found there was a “15% reduction in the expected number of crashes leading to fatal and incapacitating injuries during a three-year period after cameras were installed”. An Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) study found that (when researching cities with a population greater than 200,000) red light technology reduced fatal red light running crash rate by 21% and fatal traffic crashes at signalized intersections by 14 percent.

While automated enforcement has the capability to decrease traffic speeds and dangerous driving behavior, there is still a potential equity issue with automated enforcement. Another study of Chicago’s automated enforcement program – the same program that found a 15% decrease in expected personal injury/fatal crashes – found that cameras ticketed households in Black and Latino zip codes at twice the rate of households in white zip codes. New York City also found a disproportionate number of red light and speeding tickets from automated enforcement in communities of color. Both cities saw disproportionate ticketing rates in communities of color, despite red light and speed cameras being evenly distributed across White, Black, and Latino neighborhoods.

Even though cities like Chicago and New York have found that automated enforcement programs ticket communities of color at higher rates than white communities, many local advocates and transportation professionals believe this is not the fault of the enforcement program, but poor street design and years of disinvestment.

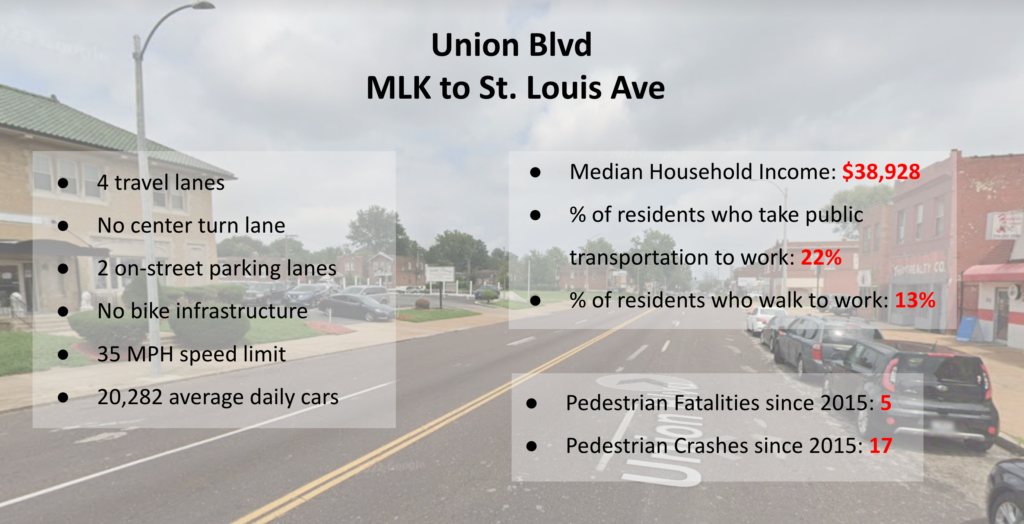

Intersectionality of Traffic Enforcement and Safe Streets

A groundbreaking article from Streetsblog NYC, got right to the heart of the intersectionality of automated enforcement and city planning/design. The article mentions that in New York City, “the city has failed to provide adequate infrastructure that protects vulnerable road users” in areas with the highest amount of traffic violations. Expanding further onto the topic, they mention how “many tickets are issued in some low-income communities of color because of the wide, speedway-like arterials that cut through such neighborhoods” where pedestrian personal injury and fatal crash rates are also higher compared to predominately white neighborhoods. In the same article, a representative from Transportation Alternatives, New York City’ bicycle and pedestrian advocacy organization, said, “high amounts of speeding violations should immediately indicate an area that DOT needs to prioritize for street safety investments”.

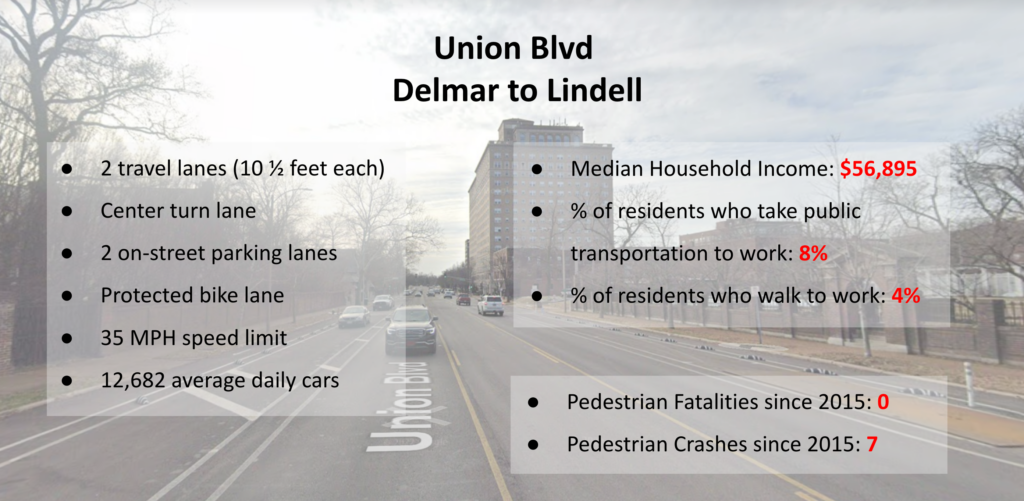

In St. Louis, there are several streets where there’s a noticeable difference in street design from one neighborhood to another. The failure to provide infrastructure that protects vulnerable people walking and biking, specifically in communities of color, has seen a greater amount of personal injury and fatal pedestrian crashes. Union Boulevard is a perfect example of this. When comparing the two roadway sections along Union, it is evident that the amount of space given to cars and the lack of bicycle and pedestrian safety infrastructure has an impact on the number of people who are killed or injured along Union every year.

The anecdotes from experts in other cities, in combination with the deficiencies in St. Louis infrastructure points towards a strategy that would build out a safe transportation system that doesn’t encourage speeding and other dangerous driving behaviors, then use enforcement strategies to fine drivers that continue to drive dangerously.

Other Traffic Enforcement Strategies

There is also an opportunity for traffic enforcement that would enforce basic traffic laws without including police officers. Several communities have either piloted or implemented a strategy that would treat traffic enforcement similarly to parking enforcement. In this enforcement system, traffic enforcement would be a department separate from the larger police department. The main responsibility of this department would be to simply enforce traffic laws by conducting stops and issuing citations without the use of force.

This department would not have the authority to search or arrest drivers, like police would. However if deemed necessary, these individuals could request additional support from police for serious offenses. A combination of automated enforcement and a separate traffic division could actually benefit police. In St. Louis, we often hear that there aren’t enough officers and resources to prevent violent crimes, specifically gun crimes. By freeing officers of the responsibility of basic traffic enforcement, there’s an opportunity for more time and resources to be allocated toward investigating and preventing more serious crimes and engaging with the community.

Discussing traffic enforcement is not easy. There are several important questions that need to be answered before increasing traffic enforcement. What is the goal of traffic enforcement? What is the preferred method for traffic enforcement? How do we conduct traffic enforcement without over policing communities of color? How do we make sure our justice and court systems can handle the influx of traffic violation appeals?

Currently, it’s very evident that our traffic enforcement strategies are not working. Traffic fatalities and dangerous driving is becoming the norm in St. Louis. Our government staff and elected officials need to take an in-depth look at how we’re conducting traffic enforcement, what the top traffic violations are, and begin implementing enforcement strategies that reflect a focus on decreasing crashes and dangerous driving behaviors. In many cities, automated enforcement is a way forward to increasing safety on our streets. But this isn’t enough. Along with enforcement, we need to start designing and building safe streets that encourage safe driving behaviors, and, as I’ll discuss in Part 3 of the Moving Forward Series, we need stricter driver’s education policies and programs that supplement enforcement and design.

* We use the term “walking” to encompass anyone who is primarily using the sidewalk to get around. By this, we mean people: on foot, in manual wheelchairs, in power chairs, and using other mobility aids.