St. Louis is one of the oldest cities in the Midwest, having been founded in 1764. Because of this, the city has many buildings that seem more in line with the ages of East Coast buildings than those in other Midwestern cities. While other places in the Midwest have buildings from before the Civil War, few, if any, have as many as St. Louis. Chicago lost most of its antebellum buildings in the fire of 1871, and many of the surviving buildings were built after 1865. Detroit, which was founded in 1701, has lost most of its 19th century buildings over the past century, as urban renewal and urban decay took many of the remaining buildings from its early years. Other cities, like Kansas City, Missouri, had only recently been founded, and were simply too new to have amassed a large collection of pre-Civil War buildings. St. Louis, which had a population of 160,000 in 1860, had a multitude of buildings from this era, and at least 700 are still extant today. The period of time in American history during which almost all of the oldest surviving buildings in St. Louis were built is known as the Antebellum Era. This period began in about 1820, and ended in 1861, at the start of the Civil War. The word means pre-war, and although it is often associated with slavery in the South, the term is applicable to any part of American history from between 1820 and 1861. In antebellum St. Louis, the pro slavery forces and the abolitionists often lived side by side. The surviving architecture from this period in St. Louis history reflects this mix of people from both the north and south. Preservation of these buildings is important to learning about the early history of St. Louis, and each of them provides historical context, and provides insight beyond what can be written down in books.

The most well-known and significant pre-Civil War building in St. Louis is the Old Courthouse. The structure was originally built in 1828 by the architectural firm of Lavielle and Morton. The current structure was built in phases between 1839 and 1862, with the original structure being replaced in 1850, as part of one of the additions to the 1839 structure. The building features Greek Revival style architecture, with an Italianate style dome designed by William Rumbold in 1855, which replaced an earlier dome, and was completed in 1862. The Courthouse served as an auction house for court ordered slave sales in the years before the Civil War. It was also the site of trials in the Dred Scott Decision, which eventually ended up in the Supreme Court, with the Scott vs Sanford case. Numerous attempts were made to demolish the courthouse in the early 20th century, but due to stipulations by city founder Augusta Chouteau in 1816, when the block was set aside for use as a courthouse, his descendants were able to successfully fight its demolition, and the building was given to the National Park Service in the 1930s. Today, it is part of the Gateway Arch National Park.

National Park Service – The Dred Scott Case

National Park Service – Slave Sales

As domes rose in Washington and St. Louis, each city sat at the edge of the war zone, commanding operations for the Union. Local officials imagined a race to completion with the U.S. Capitol, and hoped the administrative as well as architectural similarities would bring St. Louis further responsibility for governing the West after the war as well. Freed from the need for tri-regional compromise, western advocates in Congress advanced their agenda, funding the transcontinental railroad, passing a comprehensive homestead act, and establishing a system of land-grant colleges. Advocates hoped the combined political, military, and cultural opportunities of war time administration offered lasting opportunities for St. Louis and the West

The Great Heart of the Republic: St. Louis and the Cultural Civil War p 124 Adam Arenson

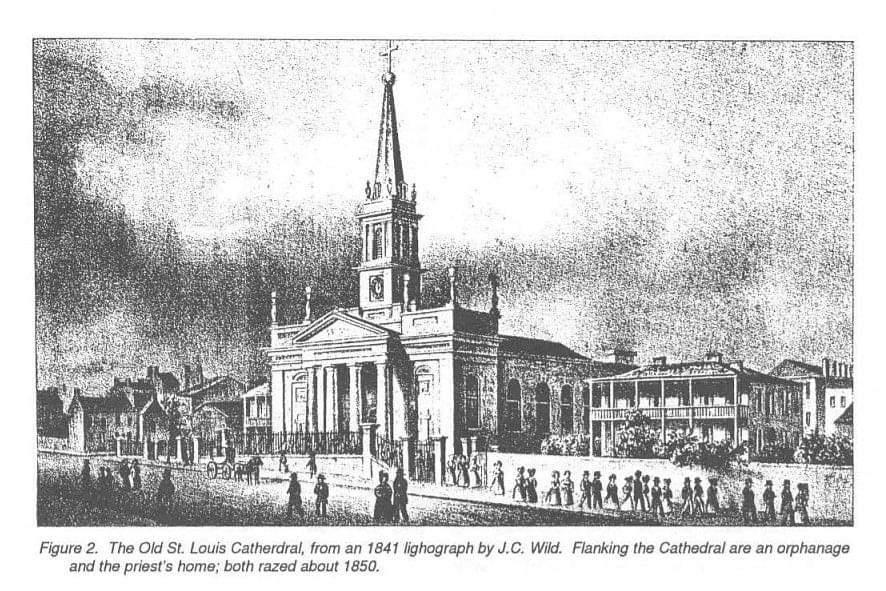

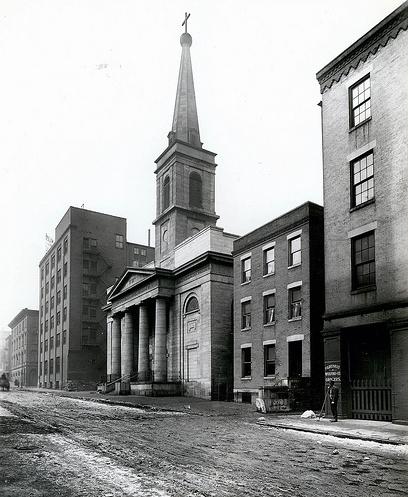

Another one of the well known antebellum buildings in St. Louis is the Old Cathedral. The cathedral sits on the only plot of land in Missouri, which has never been bought or sold. When the city of St. Louis was founded, a plot of land at Second and Walnut was set aside for a church. The original structure was built in about 1770, and was a small log building. This was replaced in 1819, and then again in 1831, when construction began on the current Greek Revival church building, which was completed in 1834. The church was the center of the Archdiocese of St. Louis for 80 years, until the new cathedral was opened on Lindell Boulevard in 1914. It was dedicated as the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, in 1961, and is one of two basilicas in the city. The other is the new Cathedral on Lindell. The Old Cathedral is also the oldest surviving church building in the city of St. Louis.

Nextstl – What “The Gateway Arch” by Tracy Campbell Tells Us About St. Louis

Many people in St. Louis are unaware of the number of antebellum buildings in the city, and this is largely due to the lack of information on many of the city’s oldest buildings. Prior to 1900, the city tax assessors records are often unreliable, and many buildings that are from the Antebellum Era are mislabeled as being constructed in the 1880s or 1890s. Many buildings which have well documented history, such as the Eugene Miltenberger House on Osceola Street in Dutchtown have been mislabeled. While the house is known to have been built in about 1855, the city lists the construction date as 1894. For lesser known houses, especially in the Soulard area, this leads to an underrepresentation of the antebellum houses and buildings in the city.

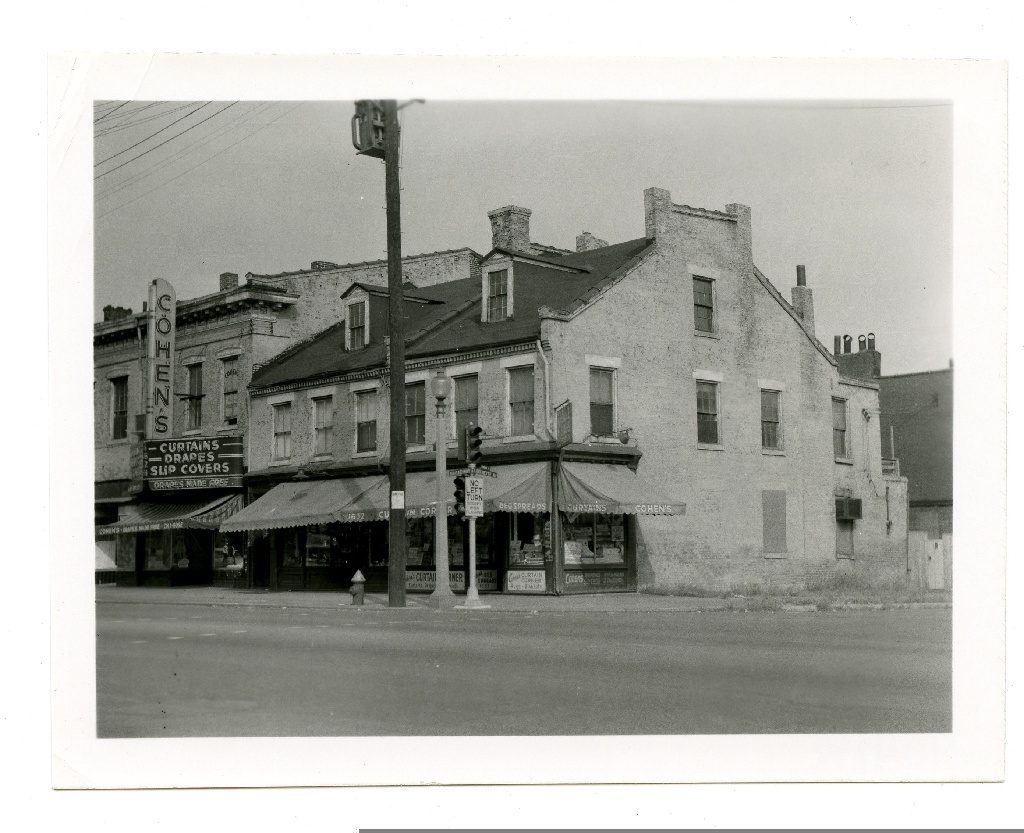

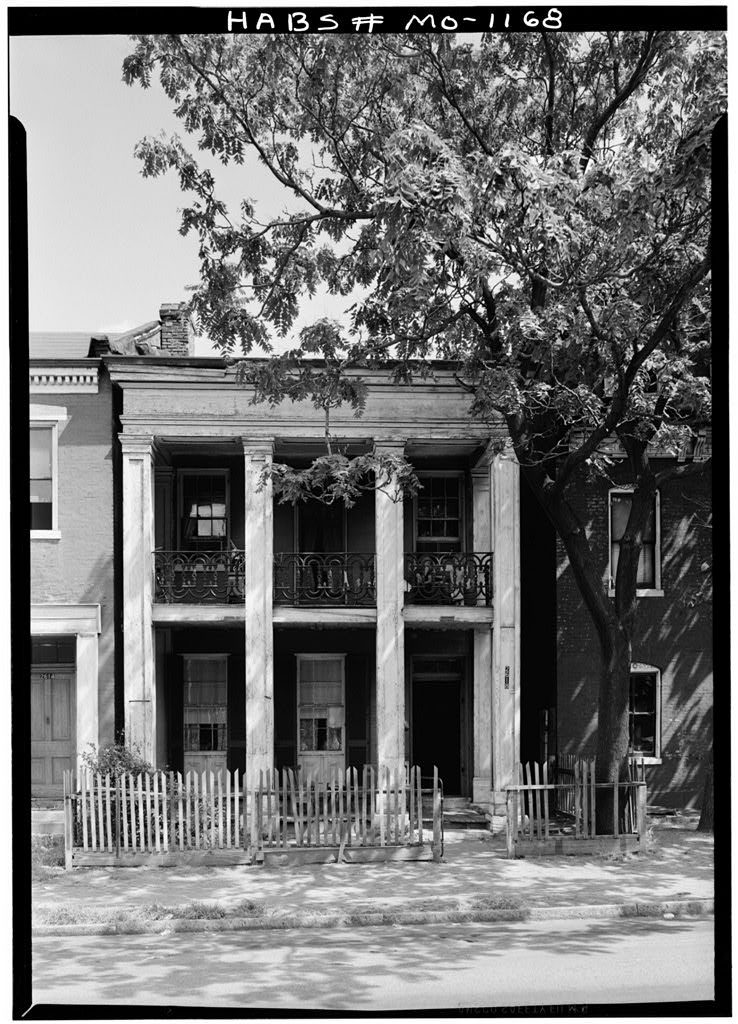

One way to look for antebellum buildings is by identifying architectural features that give clues to the age of the building. One of the most common building types from this period in St. Louis is the Greek Revival style townhouse. Key features include a pitched roof, uniform window placement, and flat tops on the windows instead of arches, which in many cases are made of limestone. While St. Louis has many different types of architecture from before or during the Civil War, Greek Revival style buildings were built almost entirely before 1865, with few exceptions.

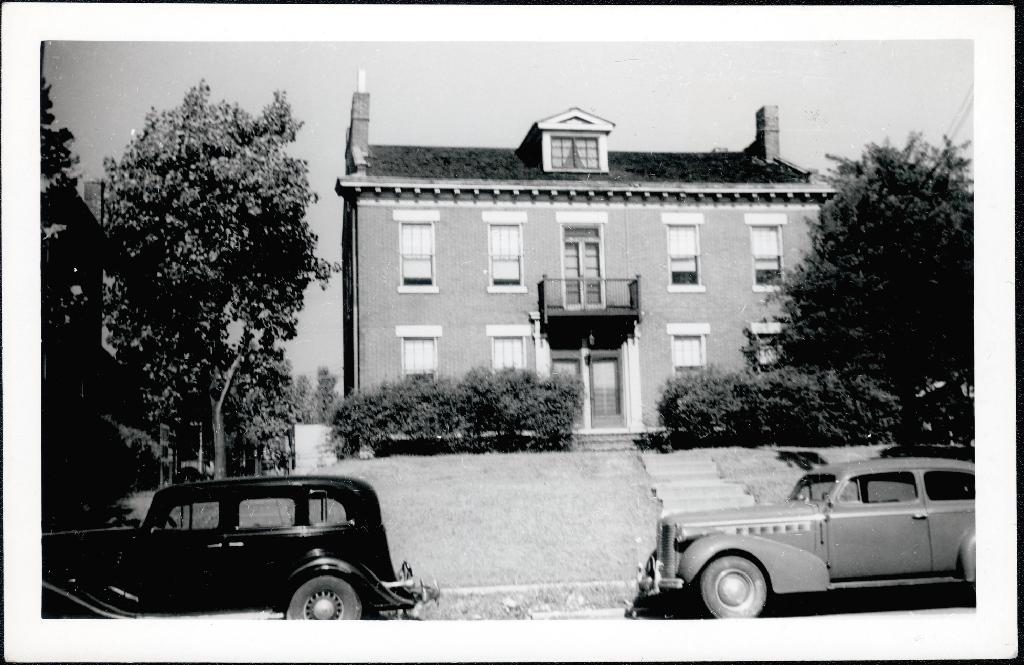

While some buildings are preserved in a near-original state, others are hidden beneath later additions. In many cases, the owners during the late 19th century added a mansard roof to the original building to keep it up to date with changing architectural styles. Some buildings clearly show their original features, such as the Matthias Backer House, built in 1856, with a mansard addition from around 1875, and others, such as the Julius Thamer brewery, at Indiana and Lynch, are nearly unrecognizable as an antebellum building, as the front facade was completely redone in about 1880. While these buildings may not look like they did in 1865, they are still an important part of the city’s antebellum history.

The extent of preservation of antebellum buildings in St. Louis is somewhat varied, depending on the neighborhood. One of the neighborhoods that has done one of the best jobs preserving its antebellum history is Soulard. The historic neighborhood was saved from urban renewal by preservationists in the 1970s, who were successful at revitalizing the neighborhood, and keeping dozens of its oldest buildings standing. Soulard was originally developed beginning in 1836 by Julia Soulard, and in the late 1840s and early 1850s, Thomas Allen began to subdivide the southern part of the neighborhood. By 1860, many buildings had already been built in Soulard, which had become a densely populated urban neighborhood in the area north of Russell. Even though highway 55 cut through as the Third Street Expressway in 1952, many historic buildings still survived. John Thielman’s house, renowned for its gallery porch, stands proudly on South 9th Street. It was built in 1850, for Thielman, who was a blacksmith that immigrated from Germany. Just a block away from Soulard Market , one of the oldest row houses in St. Louis still stands. On Emmet Street, yet another antebellum house stands, built for a bricklayer, Conrad Hessler in 1852. These three examples are only a small representation of the dozens like them in the Soulard neighborhood. Perhaps no other neighborhood in St. Louis provides such an intact example of an antebellum neighborhood.

Across the highway from Soulard is LaSalle Park, which is less intact, but still retains some of the area’s oldest buildings. It was partially demolished and partially preserved in the late 1960s, and many antebellum buildings were restored in the 1980s. Among the historic buildings is a row on South 10th Street that was constructed by the Mutual House Building Company between 1860 and 1864. It features ornate cast iron details, and at one time, it was the home of upper middle class Germans in South St. Louis. Another significant building is the St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church. Completed in November 1845, it is the fourth oldest Catholic Church in the city. The church was founded by the Vincentians, under the encouragement of bishop Joseph Rosatti, with the land being donated by Julia Soulard, who welcomed the Vincentians, due to their shared French heritage, and their mission to help care for the poor.

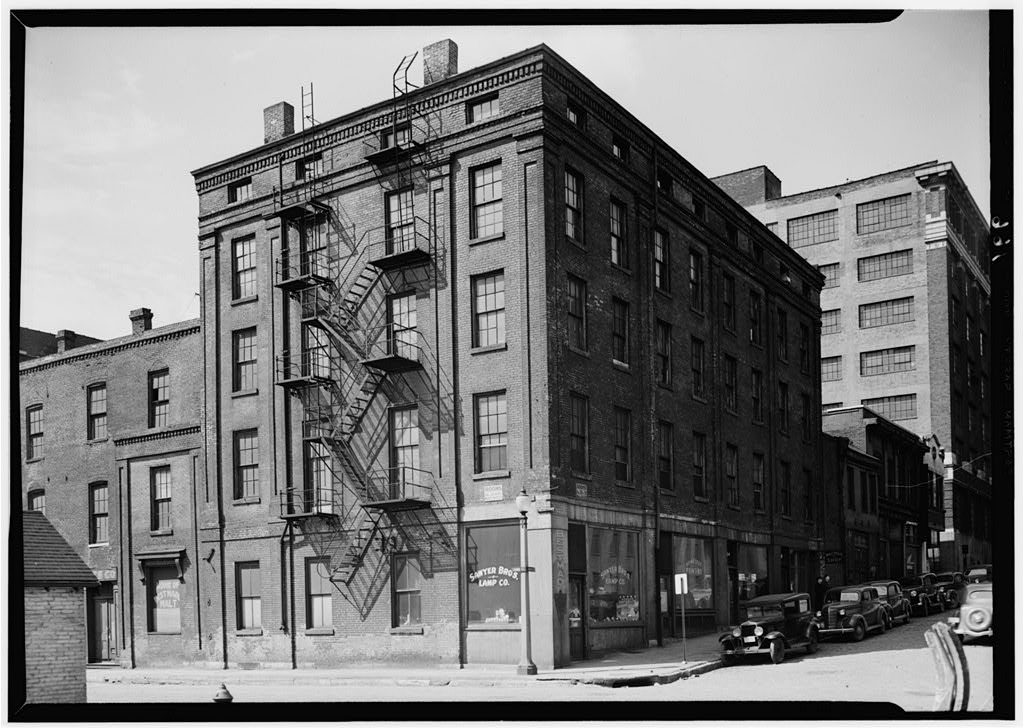

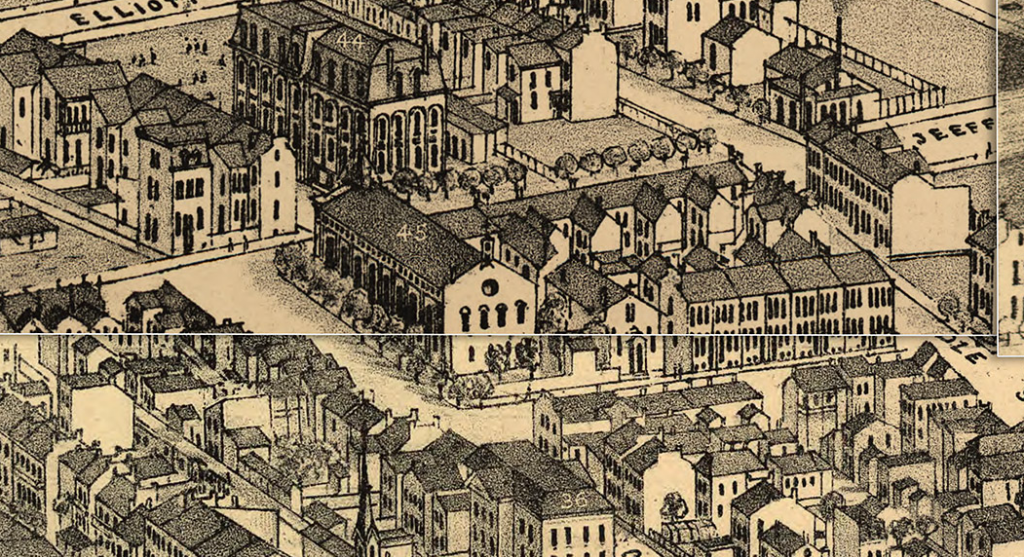

Other neighborhoods in St. Louis have been almost completely stripped of their antebellum history. Downtown St. Louis is one such area. Most cities have changing downtowns with a variety of architecture from different periods of time. However, St. Louis demolished the majority of its antebellum buildings in the mid 20th century. Outside of the Gateway Arch grounds, which are a commonly known site of urban clearance, many other parts of downtown were cleared. In the downtown south area, many historic buildings, including the Frederick Dent house (Father in Law of Ulysses S. Grant) were cleared. Of the row houses that once lined South Broadway, only a handful remain. At one time, all of downtown St. Louis was filled with antebellum buildings. In the northern part of downtown, only a few buildings on Laclede’s Landing, and a single row house from the 1840s on North Tucker remain. The urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s removed many of the others from downtown St. Louis, leaving the center of the city with only a handful of historically significant buildings from this time. Even the National Hotel, built in 1847, which at one time was visited by Abraham Lincoln, was demolished in 1948. Outside of the Eugene Field House, the Campbell House Museum, the Old Courthouse, and Old Cathedral, only a few of downtown’s antebellum buildings remain.

Another community that was almost completely stripped of its antebellum buildings was the Kosciusko neighborhood. At one time, Kosciusko was a contemporary to Soulard, and was developed just to the East of it. A significant portion of the neighborhood was laid out as a part of L”esperance’s Addition in 1839, and the area developed as a residential and commercial district centered around South Broadway over the following years. The area was later mixed with industrial facilities, which reduced the desirability of the area as a residential neighborhood. The beginning of the end for Kosciusko was in 1947, when Harland Bartholomew created a comprehensive plan for the city of St. Louis that called for the clearance of most of the older neighborhoods in the urban core, including both Soulard and Kosciusko. While Soulard narrowly avoided the wrecking ball, Kosciusko did not. Many of the industries in the neighborhood, most notably the Nooter Corporation, advocated for the re-zoning of the neighborhood to be industrial, and in 1960, this area was cleared, along with the northeastern tip of Soulard. With the clearance of Kosciusko, St. Louis lost dozens of antebellum buildings.

North of downtown, the Carr Square neighborhood was lost as well. Like Kosciusko, it had a commercial district along Franklin Ave, today’s Martin Luther King Boulevard. In the 1840s, this area was home to many Germans, and in other parts of the neighborhood, Irish immigrants created the Kerry Patch. By the 1870s, it had become notorious for poverty and crime, but it managed to survive into the 20th century, when it became a Jewish neighborhood. However, the same plans by Harland Bartholomew spelled doom for Carr Square, which was razed for numerous housing projects, including the infamous Pruitt Igoe. Gone were the shops, businesses, and historic residences from the 19th century, replaced by poorly constructed housing, most of which did not last 50 years. Undoubtedly, redlining and segregation played a significant role in the disinvestment and loss of this historic neighborhood. The last surviving antebellum building in the neighborhood, the St. Bridget of Erin Catholic Church, was demolished in 2016 for the expansion of a school building.

Other neighborhoods with antebellum buildings have mixed preservation efforts. Old North St. Louis is home to one of the area’s largest collections of antebellum buildings, due to its rapid development in the 1850s. Despite losing many of its historic row houses, when the neighborhood declined, Old North has saved numerous others, many of which seemed to be beyond repair. The area along North 14th Street underwent a significant restoration process, which saved numerous examples of 19th and early 20th century architecture, including a number of buildings from before the Civil War. However, in spite of these restorations, other areas in the neighborhood continue to lose antebellum buildings at an alarming rate.

Other areas in North St. Louis face similar issues. Hyde Park, has been successful at preserving some of the city’s oldest buildings, such as the William O. Shands House, which was built in 1851, before the town of Bremen was annexed into the city. Other early homes, at the edges of the neighborhood, have not fared as well. Hyde Park has preserved many historic buildings due to its designation as a local historic district with preservation review, but other areas have few protections, if any, for their historic buildings. Recently, the historic farmhouse once owned by John N. A. Bentzen, located on Shreve, burned down, and the remains were subsequently demolished.

The issue is not unique to North St. Louis. Carondelet, which is known for its stone houses, has multiple examples in varying conditions. The stone houses were built by German immigrants who settled in the city of Carondelet between 1830 and 1860. Some examples of the stone houses survive in excellent condition, while others have fallen into disrepair. Carondelet, which was founded which was founded as its own city in 1767, before being annexed by St. Louis in 1870, is one of the oldest parts of the city, and features a number of unique antebellum homes in a variety of different styles. The original city of Carondelet also includes the Patch neighborhood, which is home to many of the area’s historic homes. While many remain in excellent condition, others are in danger of disappearing.

Some people may question the importance of preserving the antebellum buildings of St. Louis. Many times, the argument has been made that buildings should not be saved simply because they are old, and only a few of the most significant examples should remain. In St. Louis, this has resulted in the loss of countless buildings from before the Civil War. Today, many are left standing as rare examples of once plentiful styles of architecture. Even the most common styles, like the Greek Revival, are becoming rarer and rarer, as examples are demolished.

The antebellum architecture of St. Louis is a part of the city’s story, and adds to its rich history and culture. Many other Midwestern cities like Chicago or Detroit lack such a varied collection of antebellum buildings. St. Louis has them in the hundreds. In many ways, St. Louis has trailed behind other cities, for various reasons, but one of our advantages is the wealth of historic neighborhoods that we have, which cannot be matched by younger cities like Kansas City or Chicago. A better appreciation of the assets from our early past could play a major role in shaping the St. Louis of the future. The rich history of St. Louis is one of its strongest assets. It’s about time we made use of it.