St. Louis is an old and historically significant city, with over 256 years of history. However, in its early days, it was a small frontier town, inhabited mostly by French settlers and early American pioneers before 1830. Then came the Germans. Over the course of 20 years, the population of St. Louis increased more than ten fold, from roughly 5000 in 1830 to 77,000 in 1850. By 1860, it had doubled from there to about 160,000. Many of the new arrivals in St. Louis were immigrants from Europe. Two of the first immigrant neighborhoods in St. Louis were Old North St. Louis and Soulard, which both became part of the city of St. Louis in 1841. German immigrants settled in both neighborhoods, along with the Irish in Old North and the Bohemians in Soulard. In Soulard, the Germans flocked to the neighborhood in droves, establishing numerous churches, breweries, and a turnverein in the neighborhood. The area is often referred to as Frenchtown, due to the early developers, the Soulard and Page families, being of French ancestry, but in truth, the neighborhood had become predominantly German by the 1850s. One of the developers of the area, Thomas Allen, set aside land for a German Catholic Church, which became Sts. Peter and Paul, and during the 1850s, German immigrants began to build their community in the surrounding areas. At the time, the Soulard area was often called the German First Ward, due to the overwhelming number of German immigrants who made their homes in the neighborhood.

Alongside the Germans were Bohemians, who began to arrive in St. Louis in the 1850s, and they established the Bohemian Hill community, which included parts of Soulard and LaSalle Park, as well as the area where highway 44 and 55 now intersect. Included in this area is the St. John Nepomuk Church, the first Bohemian Catholic Church in America, which was founded in 1854. The current church was built in 1870, but most of the structure was rebuilt after the 1896 tornado. For over 150 years, it has been one of the centers for the Bohemian community in St. Louis. The surrounding neighborhood was mostly fragmented by the construction of urban highways, and very little of the Bohemian Hill area remains. However, St. John Nepomuk Church holds a Goulash festival in November and a Czech festival in April, keeping the remnants of the old Bohemian community alive.

The Old North St. Louis area and the Kerry Patch were where many of the early Irish immigrants in St. Louis got their start. Many of them arrived in St. Louis looking for work, and were hired as laborers. One of my ancestors, Patrick Houlihan, immigrated to St. Louis in 1859 and started working as a laborer in this area. Some of the remnants from this period in Old North St. Louis are the row houses and tenements built in the years before the Civil War. Another remaining institution in Old North is the Mullanphy Emigrant Home, which was founded by Bryan Mullanphy, a wealthy Irish immigrant who opened the home to help poor Irish immigrants establish themselves in the city after arriving here. The home currently sits vacant, and is awaiting a much needed restoration. Most of the Irish immigrants have since relocated to other neighborhoods around St. Louis, especially following white flight in the 1950s-1970s. Today, the neighborhood has made somewhat of a recovery, although very little remains of the Irish community that once lived there.

German immigrants settled in at least a couple dozen St. Louis neighborhoods over the years, with Benton Park, Hyde Park, Dutchtown, and Baden being well known for their German cultural heritage. Today, a lot of the German heritage has been lost, however, even in Benton Park and Dutchtown. At one time, these neighborhoods featured many German establishments, but a lot have closed.their doors over the years. Many neighborhoods that once had a strong German heritage have since lost a lot of their connections to their German immigrant pasts. Many of the German neighborhoods still retain the buildings from this time, but many of the German establishments have closed.

The Irish community in St. Louis remains strong in the Dogtown area, which consists of about four St. Louis neighborhoods. In about 1900, many Irish, including my own family, moved from north St. Louis. The neighborhood is still home to many Irish pubs, and hosts a St. Patrick’s Day parade and festival every year. Some of the establishments, such as the Pat Connolly Tavern, have been in operation for several decades. Dogtown has become the center for the Irish community in St. Louis today.

Another historic community in St. Louis that has stood the test of time, perhaps better than any other, is the Hill. The Hill is the Little Italy of St. Louis, and Italian immigrants have been living in the area since the late 19th century. The first Little Italy was located just north of downtown St. Louis, but that area has long since been redeveloped. The Hill quickly became the new Little Italy after the brick factories in the area hired many Italian immigrants, who built homes nearby. Over the years, the area built a strong sense of community, and the families of the Italian immigrants stayed in the area. On the Italian side of my family, it has been a years long tradition to go to the Hill on Christmas Eve to buy ingredients for our family dinner, and to shop on the Hill. This tradition goes back to the 1930s, when they first moved there. Today, the Hill is best known for its variety of Italian restaurants, bakeries, butcher shops, and other establishments, even among those who are not part of the Italian community. Throughout the region, it is widely recognized as one of the cultural neighborhoods in the city, where the real Italian community still exists.

St Louis also has a Greek community that was once very prominent in the Central West End. For over 50 years, one of the city’s most beloved Greek restaurants, the Majestic, sat at the corner of Laclede and Euclid. However, it eventually closed, as did most of the other Greek establishments in the area, and not much remains of the Greek community in that area, as the area has re-established itself as a wealthy neighborhood over the past half century. Perhaps the only remaining part of the Greek community’s history in the area is with the St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, which holds a massive Greek festival every Labor Day weekend. Most of the other Greek establishments have since spread throughout different parts of the city and the county.

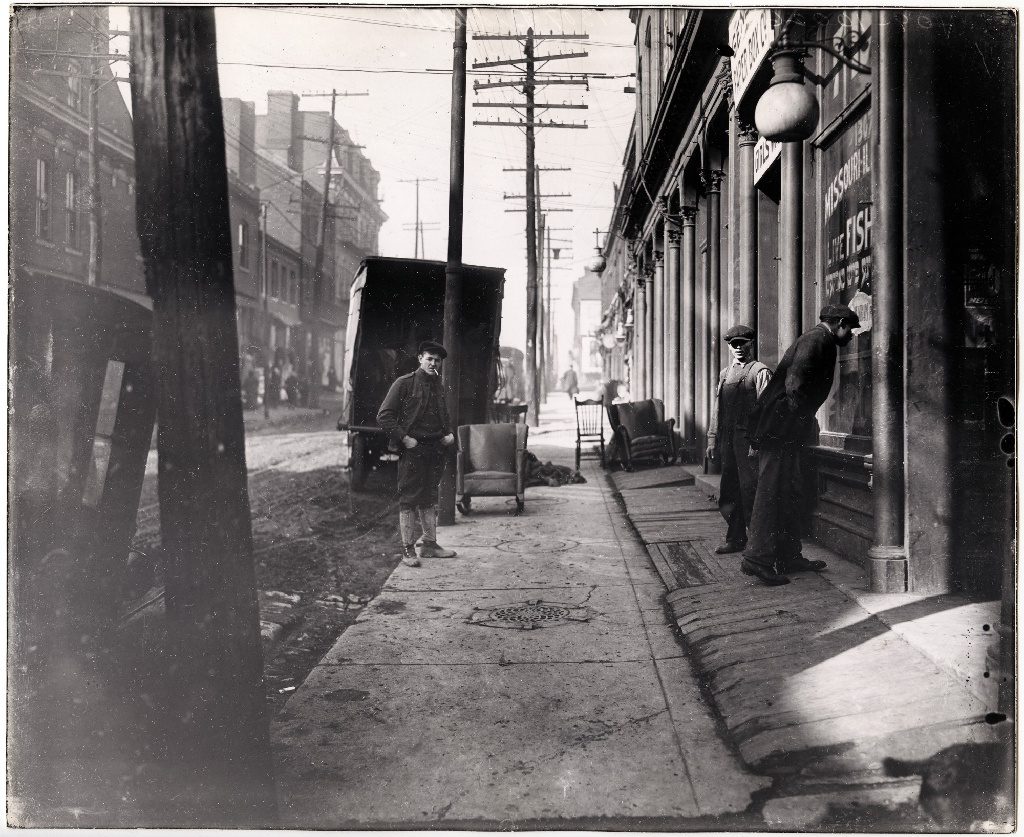

Many other immigrant communities have not been so lucky, and have been almost completely lost to history. One of those communities is the Jewish Quarter, which once existed in the Carr Square neighborhood. The Carr Square neighborhood was once part of the early German and Irish communities that were referred to earlier in the article, but by the early 1900s, it had transformed into a Jewish community. At one time, numerous bakeries and delis, along with other shops and businesses filled the neighborhood, and created a bustling urban community. However, the Jewish community left in the mid 20th century, and most of the old neighborhood was cleared for housing projects. The only remaining business is the Kram Fish Company. While St. Louis still has a large Jewish community in University City, Clayton, and Creve Coeur, the original urban neighborhood has been lost to history.

Another community that has been lost to history is Chinatown in St. Louis. Many other cities, like New York, Boston, and San Francisco has Chinatown in their urban cores. Even Cleveland, Ohio, a similar sized Midwestern city to St. Louis has one that is close to their downtown. However, St. Louis does not. At one time, in the early 20th century, St. Louis had its own Chinatown, known as Hop Alley. Hop Alley was located between 7th and 8th Streets, south of Market Street. Several Chinese restaurants and other businesses were located in the area. The building that currently houses Broadway Oyster Bar was once a Chinese laundromat. However, the urban renewal projects of the 1960s completely wiped out the neighborhood, and replaced it with Busch Stadium and the surrounding parking lots/garages. Gone was Chinatown, and in its place was a new ballpark, which previously had been located on North Grand at Dodier Street. As a result, the old ballpark area has seen a major decline due to disinvestment, and we also lost Chinatown. Today, Chinatown has relocated to a strip of Olive Boulevard in University City, which is a far more car centric suburban area, than the old Chinatown in downtown south.

Over the years, St. Louis has been a poor steward of its immigrant communities, and many of the old established neighborhoods were extinguished by urban renewal in the mid 20th century. Despite this, St. Louis has been blessed with several burgeoning new immigrant communities that have popped up in the past few decades.

One of these communities is along South Grand in the area around Tower Grove Park. This area has a densely populated walkable urban neighborhood, and it is home to several Vietnamese, Thai, Middle Eastern, and other ethnic restaurants and businesses, with a number of international markets in the area. With such a diverse population in the area, South Grand is the prime location to create strong immigrant neighborhoods, as well as maintaining the immigrant communities that have already been established in the area. The Festival of Nations in Tower Grove Park also helps to showcase all of the different nationalities that call this area home.

Another community that has been created in recent years is the Hispanic community that centers itself on Cherokee Street. The area between Jefferson and Compton along Cherokee Street is home to various Mexican restaurants, bakeries, grocery stores, and more. The neighborhood along Cherokee had fallen on hard times as people continued to leave in the 1990s and 2000s. Then, the Hispanic community began to open up numerous shops and businesses along Cherokee, stabilizing the street, and keeping it from further decline. I first went to Cherokee and it’s Mexican restaurants in 2008, and I have been going back ever since. Despite being more dangerous in that time, I was drawn to the area by what I consider to be some of the best and most authentic Mexican food in the whole area. The biggest threat to this area is gentrification and its potential to displace the community living there. To keep and maintain the immigrant community in this area, St. Louis should do more to promote this area as a center for Mexican culture in the city, and should listen to that community and what they would like to see in that area.

The Bevo neighborhood has become one of the major centers in the area for the Bosnian community. After the conflicts in the Balkan region, many Bosnian immigrants were brought to St. Louis, which now has the largest Bosnian population in the United States. The Bevo Mill was formerly a German neighborhood, but as many Germans left in the 1980s and 1990s, the Bosnian community came in to replace them after coming to St. Louis as refugees in the 1990s. However, due to crime in the area, many Bosnians have moved to South County. To keep this immigrant neighborhood alive, the crime in the area needs to be addressed.

Over the years, St. Louis has done a lot to destroy the immigrant communities that build stable neighborhoods around the city. Even so, new ones have sprouted up, and continued to add to the history and culture of the city. St. Louis needs to do more to listen to these immigrant communities, and encourage them to build and strengthen their communities, instead of trying to push them out. These communities have made strong and stable neighborhoods that add culture to our city, and add diversity to it. These communities are something that should be celebrated, as they are a significant part of the historical and cultural framework of the city.