I liked St. Louis a lot more than I expected to. It’s one of those cities where having a local friend makes the difference between two bored nights on the main tourist drag and a week of exploring its eccentricities like a local. In my five days I managed to entirely miss the tourist mainstays like The Delmar Loop and City Museum. Instead I spent most of my time delving into the cultural layers made up of the Bosnians and other immigrant populations in Dutchtown and the other formerly decaying southside neighborhoods they call home.

Immigration is a hot-button issue in the US right now, as well as throughout Europe, but I’ve yet to see a news report on any of the kinds of things I saw in St. Louis. A rapidly-shrinking city whose lifeline is immigration. Flavors of the Balkans and Southeast Asia injecting new culinary and linguistic influences into an otherwise culturally washed out city. Entire neighborhoods revived and rebuilt by refugees and their children.

In St. Louis, Bosnians, other immigrants, and their progeny are not only welcome contributors to an otherwise starved tax base: they also pay into the local cultural base.

Alongside spending five days drinking local brews and strolling through picturesque parks, I spent my time in St. Louis exploring the neighborhoods that house its small but vibrant immigrant communities. For me the fun really started when we decided to go for some Bosnian food in a totally unremarkable little building on the edge of a parking lot on Gravois Avenue on the south side of town.

Thriving immigrant populations in Dutchtown and Bevo Mill

Bosna Gold is sort of a run-down, almost divey kind of place that shares a parking lot with an equally shabby Mexican restaurant and in no way screams cultural center, but damn the food is good. Inside it looks like any other cheap restaurant in a working class neighborhood, but you won’t have to try very hard to hear the loud discussions in Serbo-Croatian (the proper name for the language of which Bosnian is a dialect) seeping out of the kitchen. Our waiter appeared to be a first-generation Bosnian-American: he took our order in unremarkable English, then passed it on to the cooks in Bosnian.

This was my first foray into the area informally known as ‘Little Bosnia‘, straddling the neighborhoods of Bevo Mill and Dutchtown and spilling over a few blocks further into the south and southwest. The next day, I went back to Dutchtown hoping for more Bosnian treats and a different look at St. Louis.

From what I can gather, Dutchtown and the entire swath of neighborhoods like it across the south side of St. Louis have historically ranged from blah to sketchy to poverty-riddled murder trap. Even now, when I talked to some local PhD students at Washington University, mentioning the time I spent wandering its quiet urban streets, most of the facial responses were confused or concerned. Why would anyone bum around this poor nothing neighborhood when they could just as easily hop up to Central West End or the Loop?

Maybe it’s not a favorite local neighborhood, but travelers and the otherwise culturally-inclined need to make a stop here when they pass through. Dutchtown has everything the rest of St. Louis needs to add its name to the list of great American cities: thriving immigrant populations, authentic restaurants, ethnic markets, and alternative locally-owned businesses. I think this might be the next neighborhood that’s waiting to be discovered in the American Midwest.

Before I even arrived in St. Louis I was curious about Dutchtown for its name, but I was disappointed to find that it had nothing to do with the Netherlands or its people. The Germans were the first to get to Dutchtown and are its namesake, as they are most other ‘Dutch’ things in the US, lazily translated from the German Deutsch.

The German settlers built Bevo Mill, the conspicuous windmill on the western edge of Dutchtown and namesake of the Bevo Mill neighborhood. After constructing this faux-Dutch relic they gave us the gift of beer in the famous form of Anheuser-Busch, leaving an eternal boozey imprint on the local culture and economy. Through the 1840s the local German population ran the widest-circulated newspaper in all of Missouri, the Anzeiger des Westens, but today the mill and the German Cultural Society building on Jefferson Avenue are among the very few visible remnants of Dutchtown’s trailblazing immigrants.

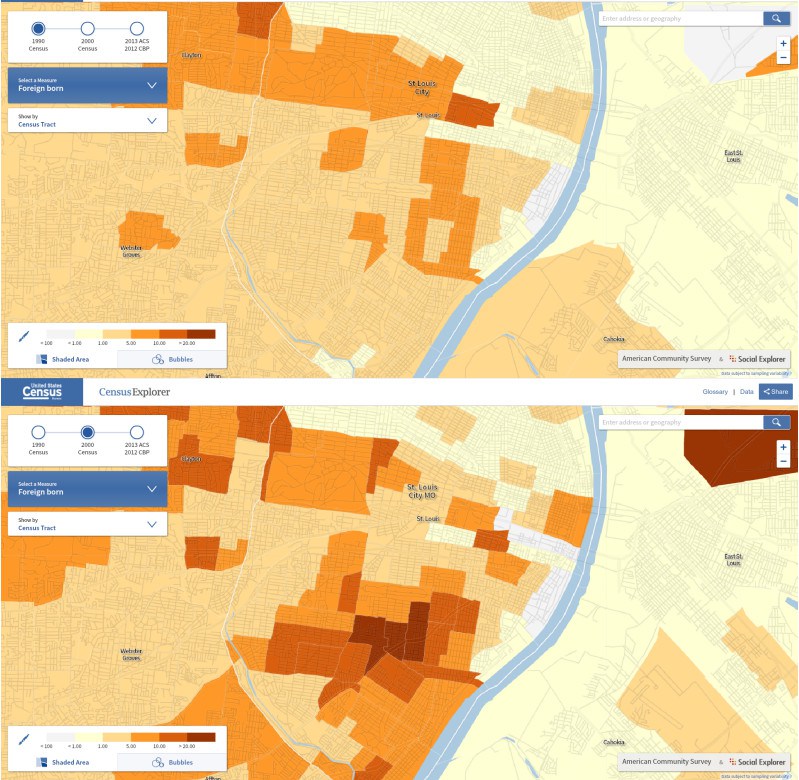

But after the Germans came and worked their busy little hearts out and moved punctually on to their next destination, Dutchtown synced up with the rest of St. Louis: another neighborhood populated by Americans, especially low-income ones, born and bred in the US, and leaving St. Louis at the first opportunity of gainful employment. The neighborhood stayed more or less that way until the Yugoslav Wars broke out in the early 90s. In 1990 Dutchtown and its neighbor neighborhoods already hosted small foreign populations, but not any notably greater than the present-day average of 7% of St. Louisians across the city who were born in another country. By 2000, ten years into the Yugoslav Wars, refugees and economic immigrants dominated Dutchtown and Bevo Mill, ranging from 22-32% of the total populations of these southside neighborhoods.

Here you see a map of St. Louis color-coded by density of foreign-born population. In the top map, from the 1990 census, you’ll see little in the way of immigrant clusters, but then by 2000, the bottom map, the areas of Dutchtown, Bevo Mill, and their surroundings have grown into a dark red, immigrant-heavy mass across the south side of town. From US Census Explorer.

Today foreign-born persons — the plurality of whom are Bosnian — make up just over 40% of Bevo Mill and the parts of Dutchtown that make up the informal area of Little Bosnia. As you head further east toward the Mississippi River, that proportion drops, culminating in the gentrifying side of Dutchtown east of Jefferson Avenue.

Little Bosnia today

Two decades after the start of the war that sent tens of thousands of Bosnians fleeing to St. Louis, the neighborhood that was once one big asylum center has grown into a place where Bosnian and other exogenous cultures have fused together into a catch-all multicultural hub. Today there are about 70,000 Bosnians living in St. Louis, and while the city overall has shrunk, this community has not only survived but thrived. As I mentioned before, just under 7% of St. Louisians are born somewhere outside the US, but 10% of city residents speak a language other than English at home. This is a sure sign of a thriving culture of heritage speakers: if there are more foreign language speakers than foreign-born people, that means children in Bosnian, Vietnamese, Mexican, or other culturally blended homes are growing up speaking their parents’ languages.

At the intersection of Gravois and several other larger roads is Bevo Mill, now a venue for slightly upscale parties and weddings. Guessing from the names of the current owners — Milan Manjenicich and Louie Lausevich — the Mill follows the greater Dutchtown theme. Bosnians have moved in to fill the multicultural void left behind by the Germans who built the mill a century and a half ago. All along Gravois — the main thoroughfare that cuts through Little Bosnia — are Bosnian-themed or -influenced businesses. Europa Market, Stari Grad, and the Bosnian Chamber of Commerce are just a few of the things that instantly meet the eye.

Further to the east, on Jefferson Avenue, you’ll find Sump Coffee sitting in a woody corner under a canopy of trees. As far as I could tell there was nothing particularly Bosnian or Balkan about it, but it’s exactly the kind of little hip alternative coffee shop that marks the birth of a cool neighborhood. Their coffee was way too sophisticated for my backpacker’s pallette, and $5 might seem like a lot, but it buys you a twelve ounce (~350ml) pitcher that’s a welcome break in the monotony of the standard cheap diner coffee I’m used to.

With historical buildings, local independent shops, and the diversity of languages heard on the street, Dutchtown is the kind of neighborhood I live for.

Coolness is immigrating to St. Louis

I think as travelers, one of the things that motivates us the most is the search for novelty. Going to a resort in Cancun with Western food and television is something we’d more likely call a holiday or a vacation than backpacking or adventure. That might be why St. Louis gets a bit of a bad wrap: it’s just really not that different from anything else.

In general. But there’s great stuff on the up-and-coming. Not only is the Bosnian community in and around Dutchtown still going strong, but the city government is actively looking abroad to expand its tax base.

In the early and mid-1990s, Bosnians were displaced from their homes, and they had to look abroad for entry-level jobs in foreign cultures with foreign challenges. Much like the Bosnians of the 90s, in 2015 millions of Syrians have been displaced from their homes. Also like their Bosnian forerunners, the Syrian population is generally well-educated (many middle class citizens speak English, French, or both) and industrially skilled, making them ideal candidates for relocation in cities like St. Louis that need to stop the bleeding of population loss. Some St. Louisians are even actively calling on their city to take in more Syrian refugees (and check out the positive, thoughtful comments on that article).

In political discussions of immigration, we debate things like whether immigrants are net contributors to or takers from economies, and we often raise concerns about culture clashes. In St. Louis, just as in many other cities in the US and around the world, the Bosnian and other immigrant populations clearly stimulate the economy, but also the local culture.

Rebuilding decaying neighborhoods like Dutchtown is the first step to the kind of urban renewal that can result in world-class neighborhoods like those of New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco, with the kind of cultural appeal that draws in not only tourism but more young professionals and domestic migrants. If all of St. Louis can follow Little Bosnia’s model, authentic restaurants like Bosna Gold and hipster hangouts like Sump Coffee will crop up all over town, and I guarantee you’ll start seeing the Gateway to the West getting more than just a blurb in the guidebooks.

*An extended version of this article originally appeared on Globalect.