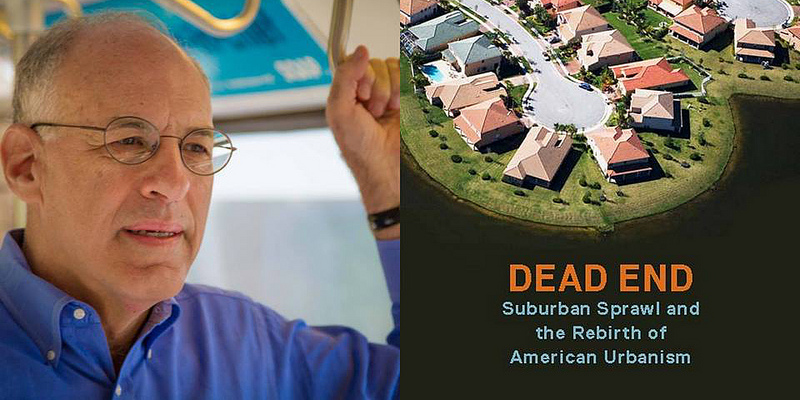

nextSTL is excited to help bring author Ben Ross to St. Louis next Thursday, September 18 beginning at 7PM. In partnership with Left Bank Books and event host and Botanical Grove developer, UIC, Ross will present his book Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism.

The overarching topic, and the specific targets of Ross’ ire will sound very familiar to St. Louisans. The dishonestly of zoning laws, the social status attained by excluding those of lesser socio-economic status, and the NIMBY and “incompatible uses” have all contributed to today’s St. Louis (and are alive and well here).

Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism Facebook event page

Ross’ comprehensive history begins with “The Strange Birth of Suburbia”, a view of suburban America as socialist commune. Subsequent chapters titled “The Age of the Nimby”, “The Language of Land Use”, and “The Politics of Smart Growth” carry the reader through to today.

For Ross, good urban policy exists in both the citizen and planner realm. He offers a smart balance of needed policy action, and public involvement based on a near encyclopedic knowledge of urban decline and suburban sprawl in this country.

In St. Louis, the lack of professional planning is often blamed for wasteful development and the subsidizing of urban decline. Today, we’re increasingly aware of suburban decline and the challenge of adapting post World War II development patterns. Better planning policy and more public involvement clearly must advance together.

At a recent book event, Ross explained the essential problem: “Developers fight with immediate neighbors and immediate community isn’t part of the larger discussion. We’ve farmed out decision making to tiny locales, which make decisions for areas and regions. Locals need input on details and specifics, but we need larger vision of what works.” We couldn’t agree more.

Our friends at Urban Chestnut Brewing Co. will provide the drinks, and Left Bank Books will have copies of Dead End for sale. nextSTL will have a couple copies to give away as well! RSVP isn’t required, but you can invite friends and help us spread the word via the Left Bank Books Facebook event page. The UIC office is located across from Olio and City Garden Montessori at 1607 Tower Grove Ave, St. Louis 63110.

Ben’s most recent writing at Dissent: A Quarterly of Politics and Culture, “Fighting Gentrification, But To What End?”

An excerpt from Dead End:

America, at the end of the millennium, could seem like one big subdivision. The suburban status-seeking impulse had acquired a life of its own. As it marched down the social totem pole, each layer of society in turn imitated those above. Fed by a vast complex of vested interests, it had swatted away the scorn of intellectuals and the lawsuits of integrationists. It overpowered even the political muscle of the real estate developers who first set it in motion. In city and town alike, single-family houses and automobiles were the unquestioned normal; any other mode of life seemed somehow deviant.

A formidable apparatus of covenants, zoning ordinances, and historic districts protected the residential pecking order. These devices preserved more than neighborhoods; they maintained status distinctions inherited from long-past eras. The 1890s, when city folk looked down on the agricultural masses, lived on in rules against farm animals. The 1920s motorist’s disdain for streetcar suburbs imposed off-street parking minimums. Preservation boards continued the 1960s search for authenticity.

But status symbols lose their power when everyone has them. The prestige of suburbia failed to impress those who grew up knowing no other life, and the values of a new generation clashed with inherited institutions. The first challenges to the suburb’s superiority over the city came in the sixties with the apartment boom and the beginnings of gentrification. By the end of the millennium, suburban living was clearly losing cachet. Highway builders still poured concrete and zoning boards chased away apartments, but the emotional foundation of the entire structure was rotting away.

Shifting status rankings were reflected in popular culture.

The late fifties and sixties were the years of TV sitcoms like Leave It to Beaver and Ozzie and Harriet. Suburban families lived the only life that was truly normal. A partial return to the city accompanied the gentrification wave of the seventies and similarly petered out in the Reagan years. Then in the late nineties, following the success of Seinfeld, Manhattan was glamorized in Sex and the City and a flood of other shows.

The suburbs were hardly forgotten, but they had a new image; it was a long way from the family in Father Knows Best to the one in The Sopranos. By 2010 the return to the city could be taken for granted; Manhattan was almost passé as Brooklyn turned trendy.

Status symbols were eroding right in front of the house. On mid-century lawns, homeowners labored to keep lawns carefully mowed and to exclude broad-leafed crabgrass from their precious turf. The intrusive species was such a symbol of suburban living that Kenneth Jackson’s history of the suburbs, published in 1985, was titled Crabgrass Frontier.

Once sod grew in front of rich and poor alike, it lost prestige. Manicured lawns have hardly disappeared; many homeowners like the look. But they are no longer a national obsession. The war against crabgrass has ended in surrender; people under thirty barely know what Kenneth Jackson’s title means. Google in 2009 rented a herd of goats to nibble down the turf around its headquarters, and this once-forbidden practice has become a fad. Cities are changing their laws to allow grazing in residential zones.

Even the quintessentially suburban game of golf is losing its allure. In 2011 in the United States 11% fewer rounds were played than in 2000. The number of golf courses peaked in 2005 and began to decline.

Yet the norms of suburbia remain deeply ingrained. Homeowners still wedded to the old values—among them most civic association leaders and many government officials—find it inconceivable that others might want to live differently. Affluent city dwellers, when too numerous to be ignored, are dismissed as hipsters acting out a soon-to-be-outgrown stage of immaturity.

Suburban nonconformity still meets stiff resistance, with concessions made only grudgingly. Nature lovers let their lawns go to seed, and neighbors demand strict enforcement of grass-cutting ordinances. A Michigan woman, in 2011, was threatened with three months in jail for growing vegetables in front of her house.

Bitter battles erupt between adherents of the now-fashionable “locavore” movement and defenders of the long-standing exclusion of farm animals from residential zones. When Montgomery County moved to legalize backyard henhouses, sharp criticism came from both wealthy Chevy Chase and more modest neighborhoods. At a public hearing, one witness called the proposal “a cultural slap in the face” at African Americans who had grown up poor. With success, she said, “they left behind the poverty and the stigma of racism associated with the chickens. For many that achievement included a suburban single-family home and neighborhood.”

Elsewhere zoning boards debate at length the fine distinctions between unproductive pets, which homeowners may harbor, and useful livestock that are proscribed. This last issue came to a head in Belmont, California, which advanced the cause of scientific land use planning by pioneering the separation of pet goats from farm animals. The city’s lawmakers adopted a 1600-word ordinance laying down conditions under which pygmy goats of the species Capra hircus may be raised in residential zones.