“When the first black people moved onto our street I saw the reactions.” “It’s not because black people moved in that white people left.” “It’s changed. It turned really dark, not that that’s a bad thing, but what comes with that is a lot of trouble.” Spanish Lake is not a film about race, but that may not be easy to discern.

Spanish Lake is a film about disposable communities, the ephemeral nature of our built environment, the lack of value we put on place, and particularly post war suburban development. It’s about a time when a consumer society, auto-centric infrastructure and cultural disruptions were creating single-generation communities for the first time.

The film is directed by Philip Andrew Morton, who spent the majority of his childhood in Spanish Lake. Upon returning to see his boarded up church and school, and his neglected neighborhood, Morton sought to document the changes he could see, but not quite understand. Smartly, the film doesn’t as much try to answer what happened, drawing a single conclusion would have been a mistake.

The film is directed by Philip Andrew Morton, who spent the majority of his childhood in Spanish Lake. Upon returning to see his boarded up church and school, and his neglected neighborhood, Morton sought to document the changes he could see, but not quite understand. Smartly, the film doesn’t as much try to answer what happened, drawing a single conclusion would have been a mistake.

While rooted in the memories of white residents from the 1970s and 80s, Spanish Lake brings a wide range of voices into the conversation. Those voices are alternatingly uninformed, barely self-aware, smart, and insightful. What the film does amazingly well, is allow residents then and now to share their story. This is the value of Spanish Lake. Interested and engaged viewers will find a lot to spur further inquiry.

First settled by German immigrants in the mid-18th Century, post-war suburban development had built out Spanish Lake by the 1960s. By the 1980s, developers had moved on to St. Charles and other farther out suburban locations. Rows and rows of new homes were being built to meet the expanding expectations of the Middle Class. Two or three bedrooms weren’t enough, children needed their own rooms. Sharing a bathroom was no longer expected. And families were looking for two-car garages. The 25-year-old Spanish Lake home was a poor candidate for renovation.

One cannot extract the issue of race from development and population movements in a city like St. Louis, and the film walks that tightrope, but timelines and memories are muddled. A statement at the film’s closing may sum up residents’ feelings the best, “Somebody was against us, and I’m not sure who.”

In 1970, Spanish Lake was 99% white and 1% black. Racial change had yet to come to the community. Multi-family housing came to Spanish Lake in the late 1960s and into the 1970s. Yet Spanish Lake’s racial composition didn’t measurably change.

Five years earlier, as the film highlights, President Johnson announced, “This administration here and now declares unconditional war on poverty in America.” The Department of Housing and Urban Development was established that same year.

In St. Louis, the issues of urban development and housing were front and center. The Pruitt-Igoe housing project had deteriorated drastically since it was it was constructed in 1955. As the public housing towers began to come down, and St. Louis County was forced by federal action to begin building affordable housing, suburban residents feared the spread of poverty.

And people were on the move in unprecedented numbers in St. Louis. In the 1950s, 100,000 people left the City of St. Louis. The 1960s saw 128,000 leave. Then 170,000 residents, more than 27% of the city’s population, left in the 1970s. They moved north, west, and south. St. Louis County was built out by about 1970 and development sprawled further.

When housing preferences change, homes age and require more maintenance, when jobs move further away, it may only take a nudge for someone to move. For some that’s race, for some it’s seeing their neighbors move, for some its the threat of decreased home values.

The community of Black Jack, MO immediately to the west of Spanish Lake incorporated in 1970 and immediately opposed and prevented plans to build multi-family housing. Other St. Louis communities had done the same, and more would come. To many, Black Jack was seen as, “A symbol of suburban resistance to federal pressure.”

Dr. Robert Schuchardt, Zoning Commission Chairman of Black Jack is shown in an archival video explaining the opposition. “The people who are out here are middle income, behave like middle income, they worry about their schools, they worry about their lawns, their property, so we have a very quiet racial integration going on in North County, and no problem with it.”

The economic thinking here is very much alive today. Following the 2010 Census showing just a 3.6% poverty rate in St. Charles County, County Executive Steve Ehlmann credited residents, stating that they avoid high-risk behavior. “Those who use drugs, drop out of school, and skirt the law are more likely to end up in poverty,” Ehlmann stated in his State of the County address.

As an unincorporated area, Spanish Lake residents had no self-determination in zoning. Very clearly, unincorporated areas, provided the path of least resistance for building multi-family and low-income housing. After all, the reason there are 90 different municipalities in the county is so that communities could better decide who would live next door, and who would not.

The Section 8 voucher program, giving rental assistance to low-income individuals and families to find housing wherever they choose, began in 1974. The film highlights a significant turning point as multi-family developments become dense Section 8 enclaves.

There’s race, there’s federal housing policy, there’s the unincorporated status of Spanish Lake, but if one were to seek a single trigger for the economic downturn of this community, it would be decreased demand for housing (which includes many factors). This economic change unleashes unethical real estate practices, blockbusting, and steering.

In the second half of the 1990s, the community changed drastically, and fast. The number of children living in poverty in Spanish Lake increased 200% in 10 years (1990-2000), a 133% increase among all age groups. In broad terms, black lower socioeconomic class residents were moving into residences left behind by middle-class white residents.

To compound the challenges quick change brought to the community, the suburban development was not equipped to provide services to its new residents. Schools struggled with burgeoning class sizes and children living in poverty. As poverty spiked, there were zero social service agencies operating in Spanish Lake. As more than one person suggests in the film, it makes little sense to push, pull, or locate those living in poverty to a relatively remote suburban location.

Something not in the film but discussed elsewhere by the director, is the idea that it was politically advantageous to isolate rising black political power. By placing low income multi-family housing in North County, the idea is that black residents would be more likely to reside in the Missouri 1st Congressional District, which then was represented by the state’s first black congressman, William Clay. Clay’s son’s represents the district today.

Today Spanish Lake is home to nearly 20,000 residents, little changed since 1980, though the past decade showed a 7.9% decrease. If incorporated, it would be the 10th largest city in St. Louis County. There was no mass exodus of people from Spanish Lake from the 1970 to 2000. The demographics slowly changed, the color of resident’s skin changed. That is what people see and remember.

Interestingly, the film makes a point to show Spanish Lake today, and gives a glimpse of what might be a nascent economic revival. The National Archive and Records Center, the largest depository of American military records outside of Washington D.C. has built a new repository capable of housing 2.3 million cubic feet of records. Applied Scholastics, a non-profit education organization affiliated with the Church of Scientology moved their headquarters to Spanish Lake. Residents recently successfully opposed a proposal to build a casino in their community, some Section 8 apartments are returning to market rate, and social services agencies are now active.

What’s largely left unexamined is whether Spanish Lake could have prevented its economic decline. Evidence suggests not. The neighboring municipalities of Bellefontaine Neighbors, Black Jack and others haven’t fared well in the disposable economy and increasing sprawl development. While incorporation as a municipality may have helped residents fight zoning changes, the 90 municipalities of St. Louis County are replete with economically failed and failing communities.

Residents were at the mercy of larger forces that didn’t care about community. There are moments of wisdom in the film, and this, offered by a Spanish Lake resident offers the most clear conclusion, “This becomes an issue of politics, power, and resources, and lower-class, poorer people don’t have those things.”

Spanish Lake is an essential film for understanding St. Louis and urban housing policy. It’s a must see for anyone interested in St. Louis and American cities. While the Pruitt-Igoe Myth allowed us to reexamine a long neglected subject, its remoteness in time dulls the immediacy of the important issues it represents. Spanish Lake brings these much nearer to today.

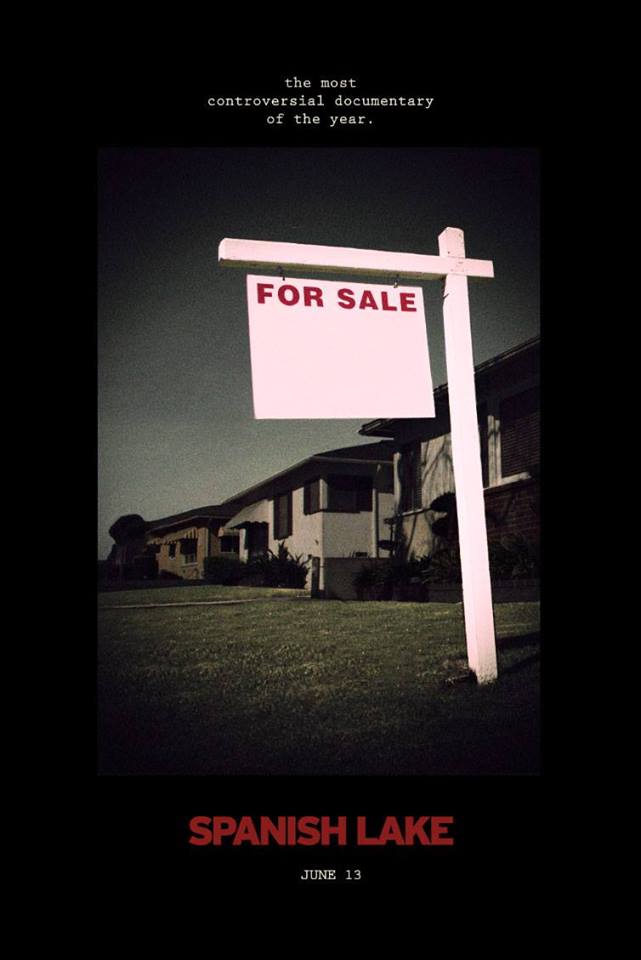

Spanish Lake opens at the Tivoli Theatre tonight and runs through Thursday, June 19. Buy your tickets on the Tivoli website and check out the Spanish Lake film Facebook page.