The City of St. Louis doesn’t have a plan. Well, technically the city does have a comprehensive plan, dating from 1948. That’s not quite fair. Although there has been no new comprehensive plan in 66 years, plenty of planning, zoning overlays, street projects, and more have taken place. There’s even a 260 page encyclopedic sustainability plan that’s spawned an initial 29 priorities across seven categories sufficiently vague and unambitious as to be meaningless. The point is that the city doesn’t have a focused plan to direct urban development. It most surely doesn’t have an operational transportation plan.

If you don’t make plans for yourself, someone else will. This is no small point for a city. Private-public partnerships and collaboration across political lines are all the rage, but in order for those to work a city must know itself, have a self-identity. St. Louis doesn’t. Why, is a topic worthy of a treatise, or two. Regardless of the cause, the result can be tragic.

State Departments of Transportation are uniquely positioned to thrive in such a vacuum. The DOT has lobbyists, maybe not their own (OK, they lobby too), but the asphalt guys, the construction guys, the roadbuilders. Politicians of all stripes love “shovel-ready” projects and the instant, if fleeting, jobs they bring. There are massive amounts of federal funds, even if today they’re less than before, and millions in state money. Municipalities are pushed to acquiesce to some amorphous regional plan. After all, building stuff is progress.

At the federal level, funding shouldn’t be a gift to state DOTs, but rather a competitive process joined by civic groups and municipalities that prioritizes what communities believe will be economically sustainable projects. A DOT, meaning department of highways, should have to compete with all forms of transportation based on return on investment. We know that cities are the most efficient drivers of the American economy. They should have more autonomy in transportation planning.

Individuals feel vastly under equipped to comment on Level of Service (LOS), traffic through put, turning radii, and other transportation jargon. Leave it to the experts. And why not? Some projects require public meetings or hearings, but these are obtuse events that only transportation wonks can stomach, and they’re ignored. If and when individuals do speak up, they’re labeled NIMBYs and told their desire for a great quality of life is superseded by the absolute need to move more cars further and faster.

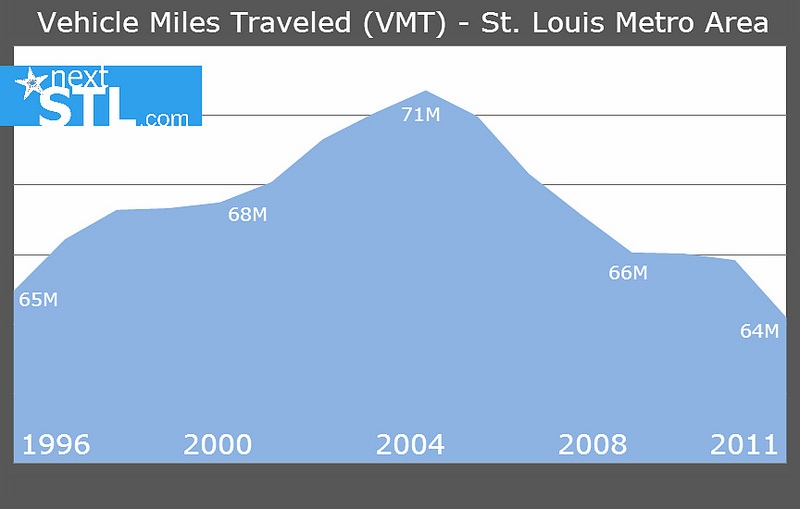

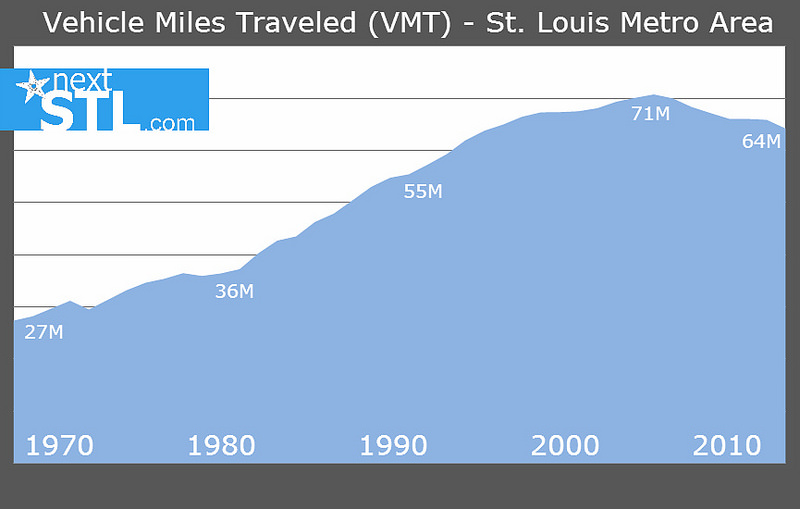

To the extent that professions possess expertise, DOTs, or in most cases Departments of Highways, are experts at building stuff. Traffic predictions, for a long period following World War II somewhat predictable, have become nothing more precise than a Tarot reading. Traffic predictions themselves however, are rather, predictable. Yet Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) has been declining in the US since 2006. For the St. Louis metro area, 2011 VMT was less than the 1996 total.

With flat population growth and VMT per capita dropping, St. Louis saw fewer miles driven than 18 years prior. VMT has decreased more than 10% across the St. Louis region since its peak in 2004. For those wondering, the Great Recession didn’t begin until the end of 2008. Research indicates no correlation between gas prices and VMT either. Best guesses for the decrease include a younger generation that values Internet connectivity and an urban lifestyle (this is everyone’s favorite because it’s fun to guess if it’s a fad and predict changes as individuals age and have children), and an aging Boomer population that will drive less and less until they die (that’s not as much fun). In fact, the later will have the greatest impact on VMT in the US for a couple decades to come (and they very well may not be replaced).

We’re still going to drive on highways in big numbers, that’s not in doubt. But given falling, or shall we be generous and say “flat” VMT, any project predicated on greater future traffic should be reconsidered. Furthermore, the even greater decline in per capita VMT means that traffic predictions adding population growth at a constant per capita VMT should be reconstructed.

And why not? We’re in a highway funding crisis right? That’s what we’re told. We’re being offered dire predictions of economic stagnation, population decline, human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together… mass hysteria! But we’re in luck. In Missouri, a “one-cent tax” will save us. Actually it’s a 1% sales tax that is predicted to generate $8B over 10 years.

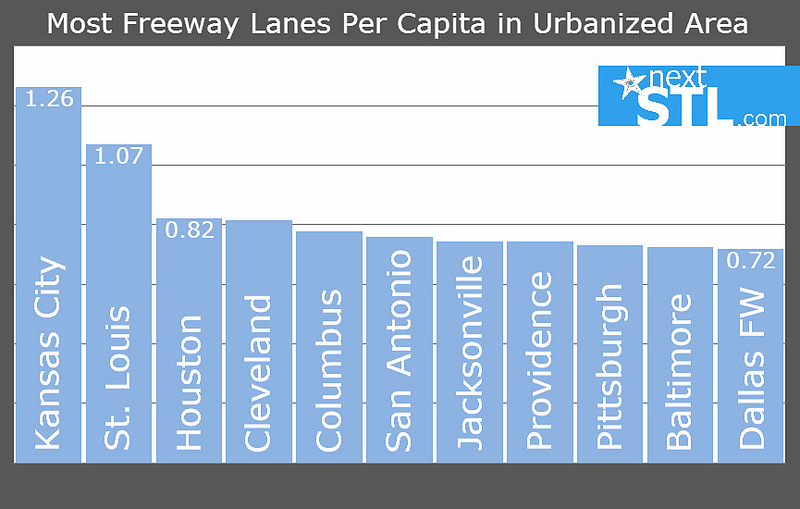

What that $8B would fund hasn’t been determined, but no one in their right mind would bet against quite a few new highway lane miles. Today, Kansas City and St. Louis have the most highway lane miles per capita of any cities in the nation. How has that worked for those two cities and the state of Missouri? How about the urban cores specifically?

For the urban core especially, population and economic strength has been in decline. Luckily MoDOT thinks they know why. From a 2008 project Environmental Impact Statement (EIS):

The core of the St. Louis region needs a functional roadway infrastructure to be able to compete with other regional economies. With mounting congestion and with more crashes, downtown St. Louis and East St. Louis will not be able to sustain new growth and development.

What a positive message. Reminds me of Keep Cleveland Strong. We need more highways or else “we will not be able to sustain new growth and development”. One transportation infrastructure development completely dominates the last half century in St. Louis – urban Interstates. How has that worked for St. Louis? What growth and development are we grappling to sustain? Perhaps the city is just one more bridge, or two more highway lanes, or three more Interstate ramps from success. What’s dangerous is that MoDOT purports to derive its policy statements from factual information. From that same EIS:

The City of St. Louis has lost much of its resident population. The City of St. Louis’ total population is now barely one-third of its post-World War II high. Only seven of the nation’s 35 largest regions are sprawling at a faster rate than St. Louis, and yet all but six of them are growing faster in population than St. Louis.

The conclusion? A few more highways ought to do the trick! It’s simply stunning to consider the ahistoric leaps in logic. Your city’s gaining population? Build more roads. People are driving more? Build more roads. Your city is losing population? Build more roads. And this in a city with 25% of its population without access to a car, and nearly 30% of its residents living in poverty (defined as annual income of less than $23,850 for a family of four). The average annual cost of owning a car? More than $7,000.

And yet we build. The $700M Stan Musial Bridge just opened to carry I-70 across the Mississippi River, meant to relieve traffic congestion on the Poplar Street Bridge, which continues to carry I-55 and I-64. MoDOT says that’s just a piece of the larger pie. About $27M is going into reversing ramps, putting a one-block lid over I-70 and removing downtown streets as part of the CityArchRiver project. Another $100M plus project will reconfigure I-55 and I-70 ramps to I-64 in downtown, add a traffic lane to east bound I-64 and slide the Poplar Street Bridge over to a add a fifth east bound lane across the river.

When a city defers its self-identity to highway building, you get highways. At some point, residents of the city must understand and speak to their own interests. This type of destructive and wasteful development isn’t any city’s fate, it’s a choice. And if a choice isn’t made, a vision not articulated and fought for? Well, the highway department gets to plan your city.

Give or take a $1B spent in less than decade, economic boom times fueled by zero traffic congestion should be right around the corner for St. Louis. The past 20 years of highway building in St. Louis has resulted in less congestion and longer average commutes, meaning St. Louis drivers spend more time overall in their cars, but less time sitting in congested traffic. Is this what we get for billions of dollars in highways? We’re sprawling faster, spending more time in our cars, and growing slower, even MoDOT knows this. Fighting congestion to produce economic development is idiotic, and also demonstrably wrong.

And what would happen if the latest downtown highway ramp project wasn’t undertaken? From MoDOT, “If we do not do it now, $30 million of Mo. State interstate funds will leave the region and go to the next highest statewide priority, and it will not return for this project.” A lesser project? “The cost to replace the bridges as they are today will be $42 million, and we will live with the traffic congestion for the next 40 years.” Forty years of congestion?! Must have pulled the Tower Tarot.

What kind of city do we want, regardless of economic development promises (guesses)? The policies of the past 60 years have failed St. Louis and cities like it. The absence of an urban political lobby, and highly fractured government, has ceded policymaking to highway engineers and their enablers. When politics does trump highway planning, MoDOT’s smart proposal is vetoed by a county executive representing 3% of traffic on a bridge.

Both encouraging and depressing is that St. Louis knows better. The East West Gateway Metropolitan Planning Organization produces high quality, smart analysis – which is promptly ignored. The council is directed by the executives of seven core metro area counties, and functions similar to how the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council operate. That is to say inefficiently and ineffectively.

Yet the East West Gateway staff continues to churn out actionable reports, recently concluding VMT in St. Louis will likely remain flat. The report, Trends in Regional Traffic Volumes – Signs of Change, recognizes that female labor force participation rates have stabilized (it has greatly increased over the past few decades, adding drivers to the roads), the working-age population is likely to decline in absolute terms over the next decade, the number of two-parent households with children is declining, and car ownership rates are not likely to rise dramatically in the future.

So how does MoDOT justify hundreds of millions in new urban highway projects? “We are following through with the commitment which will eliminate almost all of the congestion downtown.” Excellent. And bring economic prosperity too, right? Right?!