A short perspective on St. Louis written by a Washington University educated PhD anthropologist was met with harsh critiques and dismissed as “anti-American”, confused, and simply dumb by commenters across social media in St. Louis. The story was first posted on Al Jazeera – English and is reposted here in full with the author’s permission (the added images are mine). You can read the article below, followed by my extended comments and more background on Sarah, then join the nextSTL Forum conversation.

The view from flyover country

When the American Dream is dying for everyone, St. Louis might be the one to rise up

by: Sarah Kendzior

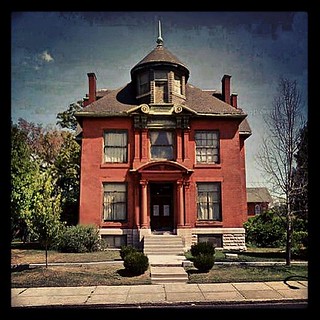

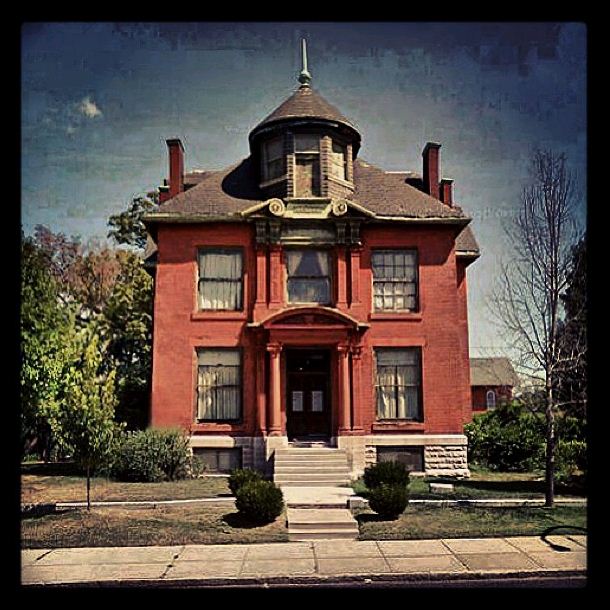

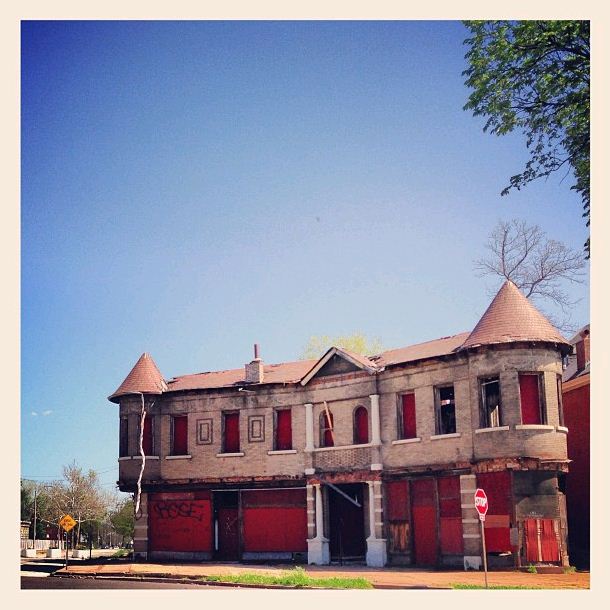

In St Louis, you can buy a mansion for $275,000. It has 12 bedrooms, 8 bathrooms, a 3-bedroom carriage house, and is surrounded by vacant lots. It was built in the late 1800s, a few decades before the 1904 World's Fair, when St Louis was the pride of America. In 1904, everyone wanted to live in St Louis. A century later, the people who live here die faster. A child born in Egypt, Iran, or Iraq will live longer than a child born in north St Louis. Almost all the children born in north St Louis are black.

In St Louis, the museums are free. At the turn of the 20th century, the city built a pavilion. They drained the wetlands and made a lake and planted thousands of trees and created a park. They built fountains at the base of a hillside and surrounded it with promenades white and gleaming. Atop the hill is an art museum with an inscription cut in stone: "Dedicated to art and free to all." On Sundays, children do art projects in a gallery of Max Beckmann paintings. Admission is free, materials are free, because in St Louis art is for everyone.

In St Louis, the museums are free. At the turn of the 20th century, the city built a pavilion. They drained the wetlands and made a lake and planted thousands of trees and created a park. They built fountains at the base of a hillside and surrounded it with promenades white and gleaming. Atop the hill is an art museum with an inscription cut in stone: "Dedicated to art and free to all." On Sundays, children do art projects in a gallery of Max Beckmann paintings. Admission is free, materials are free, because in St Louis art is for everyone.

In St Louis, you can walk 20 minutes from the mansions to the projects. In one neighborhood, the kids from the mansions and the kids from public housing go to the same public school. On the walls of the school cafeteria are portraits of Martin Luther King Jr and Barack Obama, to remind the children what leaders look like.

In St Louis, the murder rate is high and the mayor is named Slay but few think that is funny. In St Louis, things are cheap but life stays hard. In St Louis, an African-American man with gold teeth and a hoodie and baggy jeans rushed toward me in a mall, because I was pushing a baby carriage, and he wanted to hold the door open for me.

Ahead of its time

St Louis is one of those cities that does not make it into the international news unless something awful happens, like it did last week in Cleveland, another American heartland city with a bad reputation and too many black people to meet the media comfort zone. The city is treated like a joke, and the people who live there and rescue women and make concise indictments of American race relations are turned into memes.

St Louis is one of those cities where, if you are not from there, people ask why you live there. You tell them how it is a secret wonderland for children, how the zoo is free and the parks are beautiful, how people are more kind and generous than you would imagine, how it is not as dangerous as everyone says. They look at you skeptically and you know that they are thinking you cannot afford to move. They are right, but that is only part of it.

St Louis is one of those cities where, if you are not from there, people ask why you live there. You tell them how it is a secret wonderland for children, how the zoo is free and the parks are beautiful, how people are more kind and generous than you would imagine, how it is not as dangerous as everyone says. They look at you skeptically and you know that they are thinking you cannot afford to move. They are right, but that is only part of it.

St Louis is one of those cities that is always ahead of its time. In 1875, it was called the "Future Great City of the World". In the 19th century, it lured in traders and explorers and companies that funded the city's public works and continue to do so today. In the 20th century, St Louis showed the world ice cream and hamburgers and ragtime and blues and racism and sprawl and riots and poverty and sudden, devastating decay. In the 21st century, St Louis is starting to look more like other American cities, because in the 21st century, America started looking more like St Louis.

St Louis is a city where people are doing so much with so little that you start to wonder what they could do if they had more.

Rich are less rich

In St Louis, you re-evaluate fair. In St Louis, you might have it bad, but someone's got it worse. This is the view from flyover country, where the rich are less rich and the poor are more poor and everyone has fewer things to lose.

The symbol of St Louis is both a gateway and a memorial. The Arch mirrors the sky and shadows the city. It is part of a complex that includes the courthouse where the Dred Scott case was settled, ruling that African-Americans were not citizens and that slavery had no bounds.

On a St Louis street corner, someone is wearing a sign that says "I Am a Man". Like most in the crowd gathered outside a record store parking lot, he is African-American. He is a fast food worker and he is a protester. He needs to remind you he is a human being because it has been a long time since he was treated like one.

On a St Louis street corner, someone is wearing a sign that says "I Am a Man". Like most in the crowd gathered outside a record store parking lot, he is African-American. He is a fast food worker and he is a protester. He needs to remind you he is a human being because it has been a long time since he was treated like one.

On May 8, 2013, dozens of fast food workers in St Louis went on strike in pursuit of fairer wages and benefits. "We can't survive on 735!" they cried, referring to their wage of $7.35 an hour – a wage so low you can work 40 hours a week and still fall below the poverty line. At a rally on May 9, workers from Hardees and Church's Chicken talked about what they would do with $15 an hour: feed their families, pay their bills. "If we can make a living wage, we can give back to the community, and we are part of this community," a cashier from Chipotle said.

In St Louis, possibilities are supposed to be in the past. It is the closest thing America has to a fallen imperial capital. This is where dystopian Hollywood fantasies are set and filmed. It is the gateway and the memorial of the American Dream.

But when the American Dream is dying for everyone, St Louis might be the one to rise up. In St Louis, people know what happens when social mobility stalls, when lines harden around race and class. They know that if you have a job and work hard, you should be able to do more than survive. They know that every person, every profession, is worthy of dignity and respect.

St Louis is no longer a city where you come to be somebody. But you might leave it a better person.

(story end)

My comments:

I especially enjoy reading commentaries about St. Louis from those new to the city. A new voice, fresh eyes, can provide a unique perspective, an interpretation of the place we call home. To be valuable, it has to be something more than an uninformed, biased dismissal (we'll take uninformed, biased praise gladly) of St. Louis. I read the piece by Sarah Kendzior for Al Jazeera with interest. My first take: it's an interesting perspective, a broad survey of a city's history and present. Then I read the reactions of other on the nextSTL forum. I was amazed.

Not growing up here, I understand that I do not carry the same sensitivities about the city. I'm not saying that's good or bad. I feel it's OK to question whether clearing our riverfront and building the Arch was really a good idea. I get the sense that many locals disagree. And that's good. Different experiences lead to different sources of pride and varied values. What I always seek to do, however, is have a reasoned, informed discussion on the multitude of issues St. Louis faces. Some of these have aspects that are exclusive to this city. Others are national and international in scope.

Regarding the commentary itself, the one real glaring error that should always and repeatedly be challenged by St. Louisans is the depiction of the Dred Scott case. The author mentions, “the courthouse where the Dred Scott case was settled, ruling that African-Americans were not citizens and that slavery had no bounds.” This is not only not true, it is the opposite of what occurred here. Briefly, the Scotts chose to petition for their freedom in St. Louis because there was a legal community here supportive of their cause. The first case went against the Scotts, but was dismissed. The case was retried and a St. Louis jury declared that the Scotts should be free people. That’s our history. That should be our pride. The Missouri Supreme Court overruled the jury and eventually the United States Supreme Court affirmed, going further and stating that the Scotts weren’t citizens under the Constitution and therefore had no standing to petition for their freedom in the first case. St. Louis was ahead of its time.

The rest of the piece is a pasting together of observations and facts. While many chose to dismiss the content because they find the writing lacking, I think the choppy style basically works for a thousand word introduction to a city for an audience with likely zero knowledge and little frame of reference to call on. Broadly, I found the criticism of the piece to be sophomoric and devoid of substance. Charges that the whole piece is “anti-American” or that a fifth-grader could write better, reflect more on the commenter than the piece itself and are only scapegoats for substantive issues. Perhaps, more detrimental to a conversation on substance, is the defensive assertions that statements in the piece are meant to be exclusive of St. Louis. “You can walk 20 minutes from the mansions to the projects.” It’s true, that’s not the question, and the author doesn’t posit this as an “only in St. Louis phenomena”. How is one to write about anywhere if required to place everything in the context of the breadth of humanity? (“There are poor people in St. Louis.”, but, but they’re not as poor as poor people in _______ ! )

There are a number of rewarding phrases and juxtapositions in the piece for those looking for a different perspective. “an African-American man with gold teeth and a hoodie and baggy jeans rushed toward me in a mall, because I was pushing a baby carriage, and he wanted to hold the door open for me.” Far from perpetuating a stereotype, this disassembles it. It also resonates with me. Not too long after moving here I was on a bike ride in the city and was wearing bright yellow shoe covers. At a stoplight a woman rolls up next to me, very close, and rolls down her window. I’m ready to get yelled at. She does yell, “What the hell is them things on your feet?!?” She said they look like duck feet. We laughed about it.

"St. Louis is no longer a city where you come to be somebody. But you might leave it a better person." St. Louis really was the new city of the world a century ago – people came here from everywhere to make it big, people of all types were drawn here. This really was the future. Today it's not. This doesn’t mean people aren’t drawn here, but it’s true that people aren’t drawn here on the scale of Atlanta, Phoenix, Denver, Seatlle…let alone as they were just more than a century ago. The facts of today’s St. Louis seem to be what rankle locals the most. But facts don’t determine the future, they inform the present.

“(St. Louis) is the closest thing America has to a fallen imperial capital.” This would be even more evident had we not cleared the Arch grounds, Mill Creek Valley and half of north St. Louis. Perhaps Detroit is the fallen capital, but the arc of St. Louis history makes a strong case. Other fallen imperial capitals: Rome, Venice, Beijing, Istanbul, Vienna… What’s wrong with being a fallen capital?

St. Louisans have begun to realize in a systematic way, that the city and region need newcomers. The metro area has one of the highest percentages of native-born residents in the nation. The economy is stagnant. No one likes to hear someone trash their home. But this piece doesn’t do that. It’s simply a different perspective. The knee-jerk defensiveness serves no purpose and precludes any fair discussion.

A fair reading finds a lot of positive in the piece. “Atop the hill is an art museum with an inscription cut in stone: "Dedicated to art and free to all." On Sundays, children do art projects in a gallery of Max Beckmann paintings. Admission is free, materials are free, because in St Louis art is for everyone… (You tell people St. Louis) is a secret wonderland for children, how the zoo is free and the parks are beautiful, how people are more kind and generous than you would imagine, how it is not as dangerous as everyone says… St Louis is one of those cities that is always ahead of its time… But when the American Dream is dying for everyone, St Louis might be the one to rise up.”

In St. Louis we’re not supposed to talk about multi-million-dollar homes next to those living in poverty. In St. Louis we’re not supposed to notice that black children born in the city face a challenging future. In St. Louis we’re not supposed to talk about Dred Scott or the 1904 World’s Fair. In St. Louis we’re not supposed to admit that our city has an incredible history. Or perhaps we’re just not supposed to let others talk about these things.

More on Sarah Kendzior:

From PhD to Life: Transition Q & A: Sarah Kendzior

Savage Minds Backup: Interview with Sarah Kendzior

About Sarah Kendzior (publication bio)