The Land Reutilization Authority did not cause the abandonment of North St. Louis City. Paul McKee did not cause the abandonment of North St. Louis City. The process of abandonment began more than six decades ago and was fueled by a boom in automobility, federal subsidies for suburban development, racism and many other social forces at work over that time period. The abandonment became intransigent as the geographically limited city lost revenue and had few means to combat the issue. As suburban communities prospered, they took no ownership of this abandonment. The City was left to rot. It had no choice other than to take ownership of abandoned land.

The Land Reutilization Authority did not cause the abandonment of North St. Louis City. Paul McKee did not cause the abandonment of North St. Louis City. The process of abandonment began more than six decades ago and was fueled by a boom in automobility, federal subsidies for suburban development, racism and many other social forces at work over that time period. The abandonment became intransigent as the geographically limited city lost revenue and had few means to combat the issue. As suburban communities prospered, they took no ownership of this abandonment. The City was left to rot. It had no choice other than to take ownership of abandoned land.

If that’s an accurate statement of abandonment in North St. Louis City, what are we to make of the current state of the NorthSide Regeneration development area? The City has been eager to support Paul McKee, his land purchases and sought-after tax incentives. Selling 1,233 parcels of abandoned land to a private developer would make national news if it happened on a coast, or in a sexy rest belt city. The option for sale on the infamous Pruitt-Igoe site is the first private interest in decades. Does that mean, as the Mayor recently claimed, that the process has proven successful?

As I wrote in an previous piece, “…until development occurs on a large portion of the land, the strategy will only have proven that after three decades, the city has found someone else to mow the yard.” The first rumors of actual development projects are now beginning. But was land banking necessary to get to this point? The most marketable sites within NorthSide are near the landing of the new Mississippi River Bridge and the to-be-reconfigured 21st Street I-64 interchange – neither opportunity is the result of land banking.

Is there any evidence of a land banking strategy? The LRA receives abandoned parcels. Typically, the owner decided to stop paying property taxes and maintaining the property. After three years, the city moves to force the sale of the property. The property is sold at Sheriff’s Auction on the steps of the courthouse. Properties that do not receive bids (many can be purchased for taxes owed, often less than $3,000) become property of the city. There are exceptions, but this is by far the most common way the city takes possession of property.

The issue of land banking is then focused on how long, and for what purpose the city maintains ownership. Audrey Spalding of the Show-Me Institute, a free-market think tank, has been following individual efforts to purchase LRA property. To her credit, her work has done much to increase public awareness of the LRA. Specifically, the practice of designating parcels “Class C” or not “suitable for private or public use” was brought to light. In short, aldermen and the city chose to keep roughly 5,000 parcels (nearly half of the city’s total land holdings) from being listed for sale. The presumption was that such parcels were being held for future development, and possibly being assembled for larger projects.

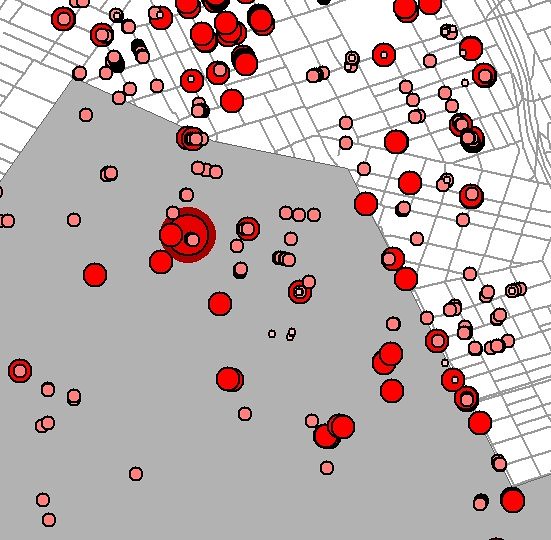

{plotting properties not advertised (red) for sale fails to reveal a clear NorthSide strategy – image by Audrey Spaulding}

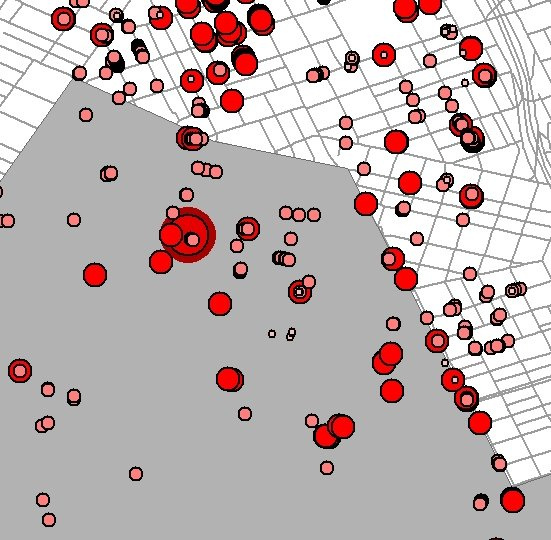

Audrey has now put together a comprehensive map of LRA property sales, property not listed for sale, and rejected offers on LRA land within NorthSide from 2003-2010. The result shows anything but a systematic plan to aid Paul McKee’s property acquisition. While open to interpretation, the mapping shows that more than 280 LRA properties within the NorthSide footprint had offers accepted from 2003-2010, while approximately 300 offers were rejected. Overall, offers on more than 2,200 separate parcels were rejected, significantly more than the 1,233 sold to McKee. Sales included properties not publicly listed for sale. For someone searching, public ownership of a parcel can easily be found using the city’s online database.

Large portions of the city within NorthSide were clearly being held, but so are whole blocks elsewhere in the city. Does this reflect a systematic land banking policy? Certainly not one the LRA or the city has articulated. For the city to now claim that the sale to McKee “proves the strategy of land banking”, is to claim a result that has not yet happened for a strategy that it did not execute.

The Show-Me Institute believes that the LRA should accept more offers. The sale to McKee puts that assertion to the test and the latest comments from the SMI are reduced to stating that even if successful, NorthSide won’t remake St. Louis and continued speculation of how many people may have been dissuaded from attempting to buy vacant land due to LRA practices.

{all offers to purchase LRA property 2003-2010, larger marks indicate higher-value offers – image by Audrey Spaulding}

{rejected offers to purchase LRA property 2003-2010, larger marks indicate higher-value offers – image by Audrey Spaulding}

Anecdotally, the LRA has not always been welcoming to private buyers, but there’s no evidence of a systematic plan to discourage sales. And so how are we to view the NorthSide development and the city’s involvement? By 1971 St. Louis needed a mechanism to deal with abandoned property. The free market (with help) abandoned the inner city, and especially the near north side. There was no nefarious land grab. The city simply accepted ownership of abandoned property.

Beginning nearly a decade ago, McKee, as a private developer, began purchasing property within what would become NorthSide. He did so from behind a curtain, but through publicly available channels, at Sheriff’s auctions and from private owners willing to sell. In this way he acquired more than 800 parcels. No eminent domain has been used to acquire property. With private transactions and added abandoned property, McKee now owns more than 2,000 parcels.

More typically, a land bank is focused not only on returning property to private ownership (and thus the tax roll), but also holding it until a sale becomes profitable. For St. Louis, this would have meant selling some parcels to McKee or another developer while holding adjacent parcels until their value increased. It typically also means aggregating small lots. McKee and the city have done this to some extent, but a quick look shows that whatever NorthSide brings, it will not primarily be clear cutting the existing urban patterns.

{a view of significant property ownership in the city’s 5th Ward, largely with NorthSide}

The City of St. Louis is in a corner, but not one largely of its own making. The sale of 1,233 parcels for $3.2M alone is a positive. The city will save hundreds of thousands of dollars on maintenance costs alone. The city simply did not have any better choices. In fact I think it’s possible that the city has done an admirable job managing the exodus and abandonment of St. Louis. At the very least, it’s difficult to envision a city policy that would have resulted in a much different outcome. After the sale to McKee, the city still owns nearly 10,000 pieces of land that it doesn’t want.

But do previous sales and holdings show any coherent strategy? Is the sale of 1,233 parcels the culmination of any plan? It appears that the answer with respect to NorthSide is no. And if that’s the case, what’s the chance that there’s a strategy to deal with other abandoned property across St. Louis?