As I sit down to chat with Mary Lou Green about Brightside St. Louis, I can tell that the first few installments of this series have left her with some questions. At the start of our interview, she asks the one question that will somehow color the remainder of our morning together. It’s in relation to the artform, the statement, the culture of graffiti.

“You love this stuff, don’t you?”

Interesting question, for sure. My response attempts to be both nuanced and respectful of her position on the topic of graffiti. For her, eradication of public graffiti is a huge part of Brightside’s efforts. It’s not the totality of Brightside, of course, but it is a big part of each day’s work, her crew of five criss-crossing the City in a never-ending quest to cover-up or spray-off aerosol paint, stickers, wheatpaste-backed flyers. You can’t exactly say, “Yes, I love this stuff,” even if you do.

To my mind, the most interesting and unexpected pieces of graffiti are those that attempt to make a wider political, social or civic point, whether through specific phrase usage, or through unique, graphic touches. For example, there’s an artist in town who’s gone on to bigger things since the days when he Sharpied moneybags on the side of light poles, newspaper boxes and little bits of urban detritus. Looking at those, you’d assume they were meant to make a comment on our consumer culture. If so, what was the wider comment? Especially when such a piece is out in front of, say, a neighborhood-styled bicycle shop?

Meanwhile, in recent months, a new name, GMO, has been appearing on walls throughout the City, both north and south. The tag is frequently coupled with images of plants, tendrils rising from the sidewalk’s surface. A statement against genetically-modified foods? Against corporations in St. Louis that specifically work in the agricultural industry? Perhaps, but things aren’t implicit, aren’t completely spelled out. GMO’s popped up quickly in the late spring. Locally born-and-bred, this GMO? Or an import to St. Louis, part of the May bombing of St. Louis by multiple, Midwest graf writers?

Another mystery. One of many.

Today, we touch on political-slash-civic graffiti. It’s a form that appears in St. Louis, in different styles and cycles. Not surprisingly, perhaps, there are parts of town where the stuff gets up more often, places like Benton Park and Tower Grove East. The dumpsters and alleys along Cherokee and its feeder streets, in particular, are loaded with the stuff if you look closely, with comments directed at the police, on a somewhat-regular basis.

We’ll start, though, with a very specific incident from a half-decade back.

Ben’s Wall

Ben Scholle and I should’ve known one another before we met. Just by sheer proximity, or through our many mutual interests and acquaintances. But as each of us worked stints on the web series “Comic Geeks,” we finally came into contact; recently, it was suggested that we re-connect, through the odd link of graffiti. Scholle’s a prof at Lindenwood, teaching film and video to the students at that university’s main campus in St. Charles. He’s also been working on a film tentatively called “War on the STL Pigs,” a work-in-progress since 2005, when he lived on the corner of Gustine and Hartford.

Living in a building with a long, white, street-facing wall, his property was tagged with the phrase that’s been his film’s working title. The words “War on the STL Pigs” were liberally spray-painted across the side of his building; he didn’t notice that the message was there, initially. Strangely, when meeting up, I tell him that I remember the phrase, can completely picture his wall in my mind; his look, though, tells me that he finds that unlikely, since the piece of agitprop was so short-lived.

“I don’t know what time it was painted,” he says. “But it was gone by one o’clock the next day. I’ll betcha that it didn’t last for 12 hours. A neighbor from across the street dropped a note in my mailbox. It made him really mad that they did this to our house. He also dropped off some paint and brushes on the front porch and offered to help paint.”

The incident caused the creation of a long-in-the-making film project. Though he says that “War on the STL Pigs” has been the title to date, it’s a provocative one; of that he’s aware, not sure that the end work will maintain that memorable, punchy title. As he recalls it, the name was borne of a time when raids on the South Side collectives of The Bolozone and CAMP were fresh in the minds of many people, coming on the heels of some localized World Agricultural Forum protests. Around that moment, various “anarchy-themed” graffiti was popping up with a bit more frequency and prominence.

He says that “the film I’m working on has graffiti as a framing device. I’m using it as a way of looking back at my own life and the lives of some friends, the ways in which we’ve all evolved between the ages of 20 and 35 or 40. At one time, I was friends with some people who maybe would’ve written that on some people’s houses. Ten year later, I’m the homeowner and I’m painting over the graffiti. That can make you realize that you’ve changed and it’s not something you’re conscious of; certain things happen and the way you see yourself from 10 years earlier doesn’t have everything to do with what you’ve become.”

In working on the film, he’s talked to Green, as well, and went on the road to record the same anti-graf crews I met with a couple weeks back. He looked for some insights from the anti-graffiti workers, themselves, but found that they weren’t especially interested in getting deep about the meaning behind their daily efforts. During the process, though, he spent considerable time questioning things, specifically the initial tag. At first, he couldn’t fully shake the notion that the event was random.

“That’s a problem, obviously, you can’t help but take it personally,” Scholle says. “There’s no question in my mind, rationally, that it was all about the location. It had nothing to do with me. I doubt they knew me, who I was. I don’t think there’s any chance that they thought I was in law enforcement. ‘Why me? What did I do?’ I’m not someone working against whoever this was. I was talking to a friend about this earlier today. She lives not too far away. And someone spray-painted ‘bitch’ on the dumpster in back of her house. ‘What, me? Why?’ Almost certainly there was no personal connection to her.

“At the time, I didn’t go looking for other, similar graffiti,” he adds. “Since then, I’ve noticed waves of certain themes. A couple summers ago, I noticed a whole lot of anarchy symbols up-and-down Choteau and Compton. For a while, I thought the anarchist snail was popping up as a sticker on every back alley dumpster. And people go on little graffiti sprees. I never noticed that our house was connected to anything else. For me, taking it personally added a whole other dimension. It made me realize that 10 years earlier, I would’ve been totally down with that. I’d have driven by that and thought, ‘Oh, cool.’ Even five years before then, maybe even the day before then. I would’ve driven by and romanticized the notion about that message. At no point in my life was I declaring war on the police. But it seemed like a cool, politically-radical message.”

Blending notions of who he’s become and who the culprit was/is has been a theme of the entire filmmaking process. An act that occurred in the span of maybe a minute of real time still resonates in Scholle’s brain, the better part of a decade later.

“I think that if there’s any way to, I’d love to figure out who it was,” says Scholle, minus any animus. “It would make a great part of the film that I’m working on. At this point, I’m sure they’ve moved onto something else. In the back of my mind, I’ve wondered what the 18-year-old me would think of what I’m doing right now. This happened so long ago, 2005, that whoever the person was that put that up could be wearing a suit-and-tie, working in the corporate life. Or they could be working in law enforcement, themselves. You just don’t know.”

McKee Town

Remembering that a few friends of mine are actively involved in Old North St. Louis’ growth as a community, I ask them about the presence of graffiti and poster messaging in that part of town. A few years ago, there was a wave of politically-tinged graffiti that popped up in North St. Louis, targeting the ongoing efforts of Paul McKee to assemble large tracts of land in North City. Owing to the presence of a few houses in Old North belonging to (both official and unofficial) collectives, there was always a little bit of extra tagging happening in that part of town.

Today, some of it remains, though many bits of written protest have disappeared. In some cases, that’s because the entire building’s gone, through fire, brick theft or general neglect. In other cases, the agitprop graffiti’s been covered up by weeds and trees.

On Monday, a friend and I wandered up to Old North, driving the blocks of this area, one of the most-unusual and unique in all of the City. Full rehabs sit on the same block with vast grassy lots. Fields are taken over by wildflowers and gardens; many of them are intentional, some of them are not. There’s a continued push on to commercially repopulate the 14th Street Mall, and to bring more residents to both rehabbed and abandoned houses. In some respects, there are few better, living labs in the City, this neighborhood continually redefining itself.

The presence of multiple buildings and lots owned by Paul McKee is another overlay to the Old North story. His presence, through various real estate holding companies, is definitely noted in the small bits of painting and stickering that exist in the neighborhood. As a friend notes, ONSL residents are a pretty diligent lot and Citizen’s Service Bureau calls are made frequently and with seriousness. Grafitti in ONSL doesn’t last all that long.

But if you look hard enough, there are hints of interesting, small-scale protest.

Here’s an old warehouse. On a streetside traffic blocker, there’s a simple message: “Total Revolt.”

Here’s an abandoned building. On one window is the word “Legacy.” On another, equally worn: “By McEagle.”

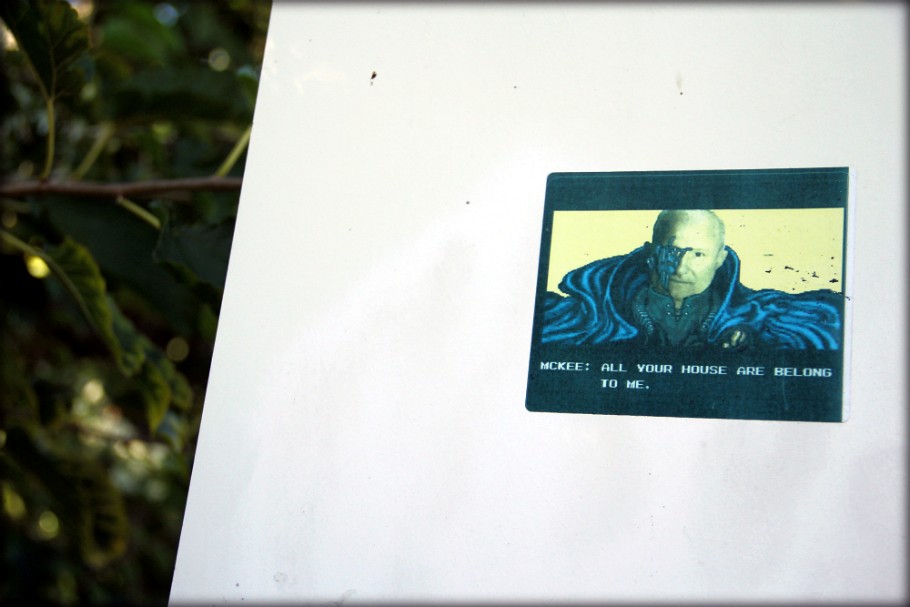

And here’s a stop sign. On the back of it, a small sticker, replete with a photo of half-man, half-robotic McKee. The message riffs off of an old internet meme: “All Your House Are Belong to Me.”

We’re given directions to some other spots of interest, but come up short on attempts to find the messages. And we’re barely out of the neighborhood, just across Florissant when an anarchy sign is picked up on a traffic blockade, surrounded by other visual gestures, including a flower.

The “Legacy” tags are found throughout North City but, as noted, they’re not as constant a presence as they were. Those responsible for writing them undertook the original effort fairly hard-and-fast; the markings were generally criticized by neighborhood activists in the communities involved and the tags ceased relatively quickly, after a big, initial burst. As time passes, these earlier marks are fading away. Other marks replace them. And more are surely to come.

For Further Reading and Viewing

We’ll start out our weekly endnotes by saying that response from the SLMPD has been sought since the first weeks of coverage. An interview scheduled for earlier this week was put on hold, due to the interview subject being called into the field. Efforts outside of official channels have also proven fruitless, but we hope to work in comments from the SLMPD within the next week, or two. Words from that entity seem not so much useful to this piece than essential.

If the phrase “agitprop” is causing you to draw a blank, here’s a decent primer from the all-knowing wikipedia.org website.

While San Diego might not be thought of as a first-choice locale for these kinds of things, there’s a group and space in that city dedicated to agitprop. If this programming were taking place in St. Louis, I’d be a regular attendee. Check out agitprop.

Here’s a nice, short piece from the International Business Times, discussing and showcasing political graffiti from around the world; much of it reflects the revolutionary spirit taking place around the world in 2012 and ‘13.

What would the topic of polticial graffiti be without some social media tie-ins? You say that you enjoy trips through Flickr? Maybe Pinterest is more your bag?

Through these past six weeks, we’ve pointed towards a variety of full videos loaded onto YouTube, some by the filmmakers, some by digital bootleggers. While we haven’t watched this one yet, it’s on the weekend to-do list. It’s “Piece by Piece,” directed by Nic Hill and dedicated to graffiti in San Francisco. It’s 78-minutes; watching just a couple of those, it seems a worthy film to watch in full: