Editor’s note: The piece originally appeared at Strong Towns

A few days ago, my local news site posted this gem of gotcha journalism about a traffic calming project in the neighborhood where I live:

While it’s been tempting to spend the rest of my workday coming up with snarky parody responses to this video (You Paid For It: Not one but two interstate highways through your downtown, resulting in 63% population loss! You Paid For It: The Rams stadium, and look how that turned out!), I know that snark isn’t the answer. Because this journalist isn’t the first person — or even the first journalist — to talk trash on a traffic calming project that’s likely to make my neighborhood safer and wealthier. And when it comes to projects like this nationwide, he certainly won’t be the last.

This is the uncomfortable reality of the movement to #slowthecars in our human-scaled neighborhoods; all too often, drivers really, really hate being slowed down. And a lot of them will stay angry, no matter how beautifully you argue that narrowing your road makes your neighborhood immediately safer for all modes of transport — and let’s be clear, it does. There’s no magic wand that will force all your neighbors to be happy about changes to the streets they drive down every day — much less stop them from flooding the alderwoman with calls to get the “hazards” removed, especially when the nightly news is all but telling them to do it.

Does that mean we shouldn’t #slowthecars? Nope. The safety and financial productivity of our cities is far too important.

But it does mean that we can and should get a little better at implementing traffic calming measures each time we attempt them. That’s the essence of the Strong Towns approach.

Here are a few lessons I’ve learned from my neighborhood’s Great Concrete Ball saga of 2018 that might help in your town too.

1) CALM THE STREETS THE NEIGHBORHOOD CHOOSES

The Compton Corridor spheres weren’t installed on a whim. They were actually something that the community asked for by name — and that’s something that all of our communities should strive for.

Since 2013, Alderwoman Christine Ingrassia has instituted a participatory budgeting process to solicit citizen feedback on how the ward should spend their share of city tax dollars to improve their neighborhood. Multiple residents, Ingrassia says, pointed to slowing down Compton as a high priority.

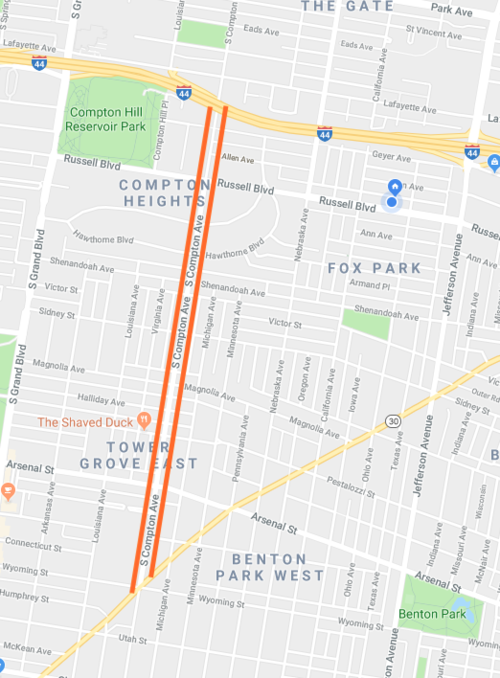

As one of the only through-streets in a mostly residential ward bounded by stroads and a highway, cars frequently use Compton as a cut through, ignoring posted speed limits and blowing through the neighborhood’s nearly block-by-block stop signs. While Compton is by no means a stroad — it has one lane in each direction, flanked by parked cars — the street’s wide lane width, roomy intersections, and proximity to high-speed arterials communicate to drivers that they can safely speed up, resulting in an often harrowing experience for walkers and bikers, and more than our neighborhood’s fair share of car crashes. Ingrassia noted that some residents had had multiple parked cars sideswept and totaled by those just passing through.

Ingrassia’s choice to tap into the knowledge base of her constituents when deciding how to improve the neighborhood was a wise one. I, and nearly all of my civically involved neighbors, knew about the proposal long before the first ball was bolted to the ground, and we felt a sense of ownership and advocacy of it from day one.

What Ward 6 could have done better — and this is every town’s challenge when it comes to meaningful community engagement — was to reach out even more. When it comes to your town, providing childcare to busy parents who can’t otherwise attend budget meetings, expanding meeting times and venues to reach more people, and devoting more resources to developing deep relationships in the neighborhood and publicizing these initiatives far and wide can always help more neighbors feel involved in the process.

2. Build incrementally.

Of course, many of the most vocal detractors of the concrete balls aren’t people from my neighborhood at all — they’re the drivers that use Compton as part of their daily commute, but don’t actually stop to walk around and experience the neighborhood as a resident might.

There are limits to how much buy-in you can build among drivers like these, especially if their only priority is cutting a few minutes off their trip (and everyone else’s safety be damned). But implementing traffic calming measures in incremental phases can act as a visual warning that a project is coming, even to those just passing through — and give leaders a chance to hear and respond to feedback before the concrete is poured.

The Compton ball project actually began with nothing more than paint on the ground (see video below) — an inexpensive move that piqued driver curiosity and attracted media attention, getting the word out about the changes long before they became permanent.

While a few more incremental steps could have followed (I would have loved to see the neighborhood try a basic tactical urbanism demonstration, (and possibly a few more temporary interim designs) before we committed to the specific solution we chose) the ward’s decision to phase the measures in gradually was a smart way to inexpensively test the waters while also giving road users an early heads up. (The fact that Ingrassia says the ward remains committed to re-evaluating the spheres over the next year and iterating their effectiveness is even better.)

3. BEAUTIFY (or at least make it cute)

One of the odder aspects of the pushback against the Compton spheres has been drivers’ insistence that they simply can’t see the balls.

Standing far above street level on flat, well-lit roadways with clear sight lines, it’s hard to understand how this is possible; or as journalist Chris Naffziger says, “If you cannot see a giant, two-foot-tall, gray concrete ball against a backdrop of red brick, glass or shrubbery, you should not have a driver’s license.” But that doesn’t mean that a little color is ever a bad idea.

It’s easy for an irate driver to look at a concrete traffic calming prop and only see a dangerous impediment. Throw some paint on it, though, and it can become a piece of public art that they enjoy slowing down to marvel at, rather than cursing as they swerve to avoid it.

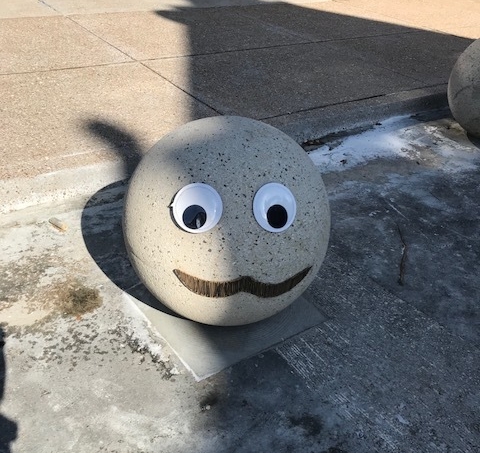

Residents of my neighborhood understood this instinctively. One of my neighbors knitted a pom pom hat for the ball; when it went missing, another mystery neighbor duct taped googly eyes and a mustache to it. And it should be noted the committee’s decision to install spherical bollards in the first place was, in part, a gesture to the importance of aesthetics; they even selected a designer who was a protege of Bob Cassily, the creator of our city’s famous, utterly singular City Museum.

Whether you choose to invest some money to beautify your traffic calming measures — I love Michael Allen’s suggestion of hosting “the nation’s first concrete bollard art biennial” on Compton — or just raid the craft store to make it temporarily a little cuter, changing the look of a concrete object can be an easy, inexpensive way to shift the conversation.

4. CELEBRATE

The biggest missed opportunity on Compton? They haven’t thrown a party.

Traffic calming measures aren’t just concrete and strategic design: they’re a clear signal that drivers don’t own the roads we live on, and that our streets are where residents live, not just where we drive our cars. Marrying the installation of the Compton balls with an open streets event that celebrates all the things we can do in the street besides drive a car would have been a fantastic way to send a message that Ward 6 is behind the balls. We can still do this — and maybe use it as an excuse to get those things painted, working together as neighbors.

5. Educate.

I put “education” last in this list on purpose. That’s not because I don’t think it’s important to help our fellow citizens understand why it’s so crucial that we slow the cars; on the contrary, I think a broad, cultural shift in how we understand and talk about our streets is the only way our cities will ever thrive, which is why I work for Strong Towns. But when it comes to implementation, traffic calming needs to be visual, impactful, and most of all, instinctive — not something that every driver needs a lecture to understand.

So when you do get into a conversation with someone who’s resistant to the traffic calming measures, take a breath.

If I found myself in a conversation with the “You Paid For It” host, I might point out that my tax dollar didn’t pay for “concrete balls in the street” — they paid for a safer, calmer, and more financially productive neighborhood for myself and the rest of my neighbors.

I might argue that the fire department approved the measure, so any argument that it’s impossible for large vehicles to turn is just false — and that making it difficult for any vehicle to make a turn at high speed is literally the point of the measure, because “difficult for a car to turn” is a much better alternative than “difficult for a child to cross without getting hit.”

I might mention that the scare tactic of flashing the $235,000 bill for the project across the screen is just that — a scare tactic — because traditional bump outs at a single intersections would have cost more than all of the Compton balls across four intersections combined.

And I’d certainly mention that the fact that people are hitting the balls at enough speed to knock them off their foundation is the best evidence I’ve heard yet that we have a major speeding problem in our neighborhood, even if I agree that we need a design solution to keep them from rolling off when they’re struck.

But mostly, I’d challenge a detractor of the Compton balls to really pause and think about what they mean by “safety.” We’ve become so used to forgiving road design that we’ve forgotten what that design really forgives: cars running off the road, which is not so forgiving to a passing pedestrian.

The safety of a vehicle cannot and should never outstrip the safety of a human being, no matter their mode of transport. As advocates, we have to make that case clearly and convincingly to everyone in our communities.

(All photos by Kea Wilson)