I recently read a quote:

“Historic preservation is often linked, hand in hand, with ideas of placemaking, where preservationists embed their work in a neighborhood, community, or landscape to highlight what makes that place unique and preserve its character. In doing this work, preservationists make evaluations about a place’s beauty, integrity, and significance. In the United States, the criteria on which they base these determinations come largely from the standards listed in the National Register of Historic Places’ nomination process. As the work of historic preservation has evolved in recent years, however, many practitioners have begun to push back against these limited criteria. More people are looking to tell the stories of underrepresented communities, document and protect vernacular architecture, preserve sites of the recent past, and promote the protection of intangible heritage.

— The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook – June, 2019

The following stuck with me: “More people are looking to tell the stories of underrepresented communities, document and protect vernacular architecture, preserve sites of the recent past, and promote the protection of intangible heritage.”

I’m a story junkie and couldn’t agree more. The lost perspectives of people with alternate recollections of history are sometimes the most enlightening. The more I read, the more I know how incomplete historical documents are without these stories. Sometimes the stories of the less represented are the most fascinating and the perspectives I crave.

Just read Tales of a Talking Dog for a lesser told history of the emptying out of North St. Louis from a white person’s perspective, to balance the historic narrative on that part of town. It’s essential reading for the open minded.

I had someone reach out to me who was interested in a building at 3600 South Grand. I knew of this building from research on lost cinemas of St. Louis, and reading about development on NextSTL and CitySceneSTL.

I am speaking of the Grandview Arcade, or Melba Theater building at South Grand and Miami Street in the Gravois Park Neighborhood.

I’ve written about this a couple times, back in 2015 and 2018.

This section of South Grand, just south of Gravois has evolved over the years and has been part of my real life and online reading for years. I used to go to a Greek diner just south of here in the mid-1990s. It was once a teeming shopping area when a Sears (one of two in St. Louis) was just down the street. This 1920s art deco beauty was sent to the landfill for the lust for modernization.

A new building was erected here, urban in form, arguably useful for the neighborhood, but so much deco architecture and sense of place lost. Read Vanishing STL for an excellent entry on the saga of this building.

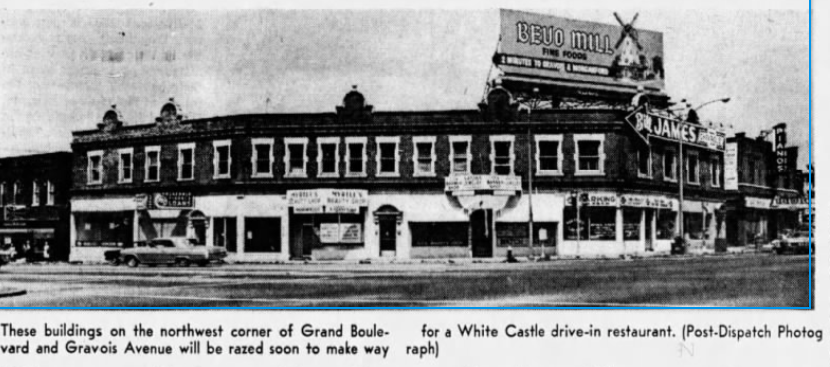

There was also a set of beautiful buildings on the northwest corner of Grand and Gravois.

These were destroyed not long after the photo below was taken for the suburban ideals of the time: drive through fast food. We are now left with a less than desirable White Castle, KFC and Walgreens…all with surface parking lots and low density drive throughs a la the suburbs all across America.

Back to the Grandview Arcade building: I know it’s important, I know it’s beautiful, I know it’s in a tough section of the neighborhood.

I went to the Pizza A – Go – Go restaurant when I first moved here. But I always thought it’d be torn down. Luckily, it was purchased by Garcia Properties, who intend to rehab it and return it to mixed use. They are doing amazing work in our city, by the way. Look no further than the work they have done along South Kingshighway just north of Chippewa. Those blocks look better than they have in maybe twenty years.

But, I’m here today to write about why destruction and demolition, taking place at staggering rates in parts of our city, mostly North City, are hurting us as people and as a city.

So much goes with the mindless, short-sighted destruction of buildings. “Eye sores”, they will tell you. Homeless people, drug dealers, street sex workers, squatters, graffiti taggers…the list goes on from those who seek short term solutions: get rid of it, it’s too far gone, they will tell you.

It’s not the buildings themselves that are the problems though, it is usually the gross abandonment, neglect and neighborhood decline at all levels.

But it’s not just the local politicians and groups of locals who should have a say on whether a building is razed. Hold your horses. Let the larger citizenry weigh in on why these buildings are important before they are stripped from our landscape and history.

Case in point: Peter Tao, a local architect from TAO + LEE, reached out to me to ask if I knew about the Grandview Arcade’s history. He happened to be researching some family history, as well as Chinese-American history as part of a Missouri Historical Society Collection Initiative (more about this later).

Peter, a native St. Louisan and Chinese-American, recently dealt with his parent’s passing. They were amazing people whose St. Louis history crossed paths with this building in the 1950s, so Peter was searching for some answers.

Peter’s father, Tao Kwang-Yeh (later William, or Bill to many) and mother Guo Yu-Tsai (later Anne) started up their first business, an engineering firm in this exact building, in 1955. Starting a business is the often told story of the immigrant’s dream of coming to America.

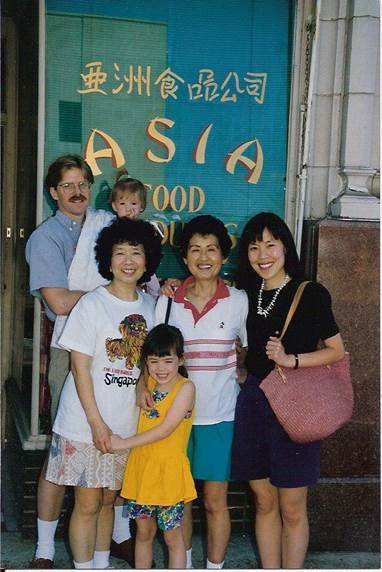

And, as it so happens, during Peter’s search he discovered that there was another Asian-American history story and connection with this building. Notice the Chinese lettering atop the building, and the retail sign to the left).

This photo (estimated to be circa 1960s) was discovered in Peter’s father’s collections and was presumably William Tao’s effort to visit his own past.

The Chinese sign roughly translates to On Leong Merchants Association. Peter noted the direct translation is An Liang Gon Shan Huei. An = peace, Liang = good, Gong Shan Huei = union or gathering place or Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

On Leong is the Cantonese pronunciation of An Liang (Mandarin).

So this building on South Grand and Miami had a link to Chinese-Americans.

I had Peter over to the house in November, 2021 to meet and talk about his ongoing research and experience. His family’s history is nothing short of fascinating and eye opening. I’m thrilled he was willing to allow me to share part of his story here.

This story is a collaboration between Peter and I. Mostly, my opinions and Peter’s amazing story, photos and personal research on this building.

Peter’s parents immigrated to America in the late 1940s, shortly after the end of Japanese occupation of China, in the midst of civil war and the rise of Mao Zedong. They were in search of bettering their lives and seeking opportunities after enduring years of hardship and oppression.

With workforce advancement having been suspended due to the war, China offered incentives to its talent pool to advance their education where opportunity could be found. Tao Kwang-Yeh, already a young engineer, found a graduate engineering program opportunity at of all places, Washington University in St. Louis. It so happens the Mechanical Engineering Department Chair was Raymond Tucker, who offered Kwang-Yeh a graduate student teaching position. Raymond Tucker became his teacher and mentor and eventually, the Mayor of St. Louis. This mentorship and helping hand to this young immigrant became a great influence in the lives of Bill (and Anne), where they in turn would welcome young newcomer Chinese students, then embark on a life of mentoring and supporting institutions such as Washington University and the International Institute of St. Louis, to name a few. Bill Tao would become a trustee at Washington University and eventually be bestowed with an honorary doctorate degree.

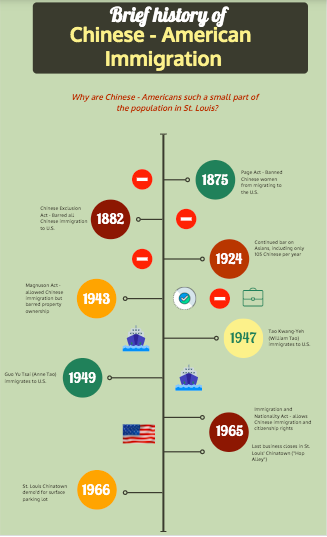

Asian immigration to the U.S., specifically Chinese immigration, has been a long-time struggle. Many exclusionary laws, originating with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, were enacted by Congress to keep Chinese people out of America, and later to prohibit Chinese immigrants from owning property and businesses. This was the only law in U.S. History to ban an ethnic or national group. This finally changed in 1965, with the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Commonly known as the Hart–Celler Act. It took 83 years for the Chinese to finally be included.

I’ve long wondered why more Chinese folks didn’t settle in St. Louis. The brief timeline above is a start toward a greater understanding of just how hard it was to get to the U.S. from China. Our racist history spells it out pretty vividly. Chinese were not allowed open immigration by the Federal government.

While things finally changed in 1965, St. Louis had lagged far behind as a place where Asian-Americans chose to call home. The suburbs in St. Louis County are a place you will see many Asians, but not so much in the City of St. Louis. Per the 2020 Census count, 12,289 St. Louisians are of Asian descent, about 4% of our total population. Keep in mind that Asia is the largest continent on Earth, so only a small subset of that 12,000 are Chinese-Americans.

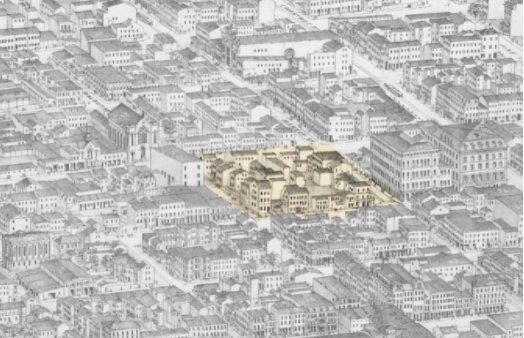

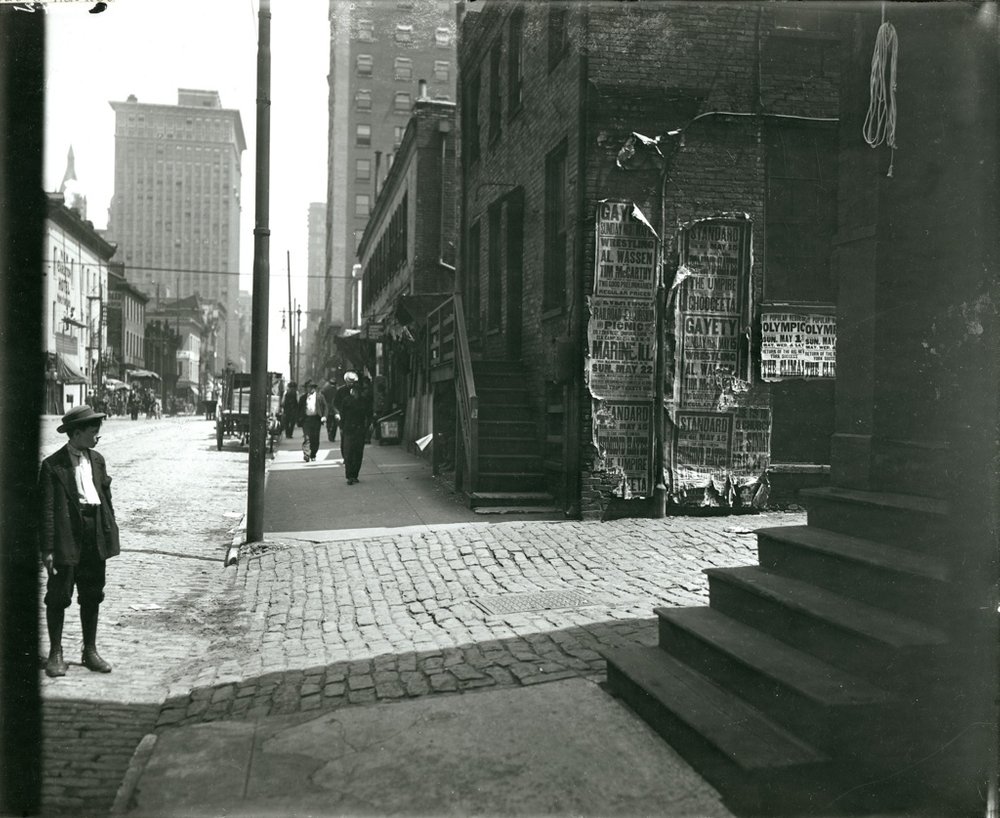

Historically, St. Louis did have a“Chinatown”, of sorts, later dubbed “Hop Alley”, from 1869-1966.

“The first Chinese immigrant to St. Louis was Alla Lee, born in Ningbo near Shanghai, who arrived in the city in 1857. Lee remained the only Chinese immigrant until 1869, when a group of about 250 immigrants (mostly men) arrived seeking factory work. In January 1870, another group of Chinese immigrants arrived, including some women. By 1900, the immigrant population of St. Louis Chinatown had settled at between 300 and 400. Chinatown established itself as the home to Chinese hand laundries, which in turn represented more than half of the city’s laundry facilities. Other businesses included groceries, restaurants, tea shops, barber shops, and opium dens. Between 1958 and the mid-1960s, Chinatown was condemned and demolished for urban renewal and to make space for Busch Memorial Stadium.

— Wikipedia

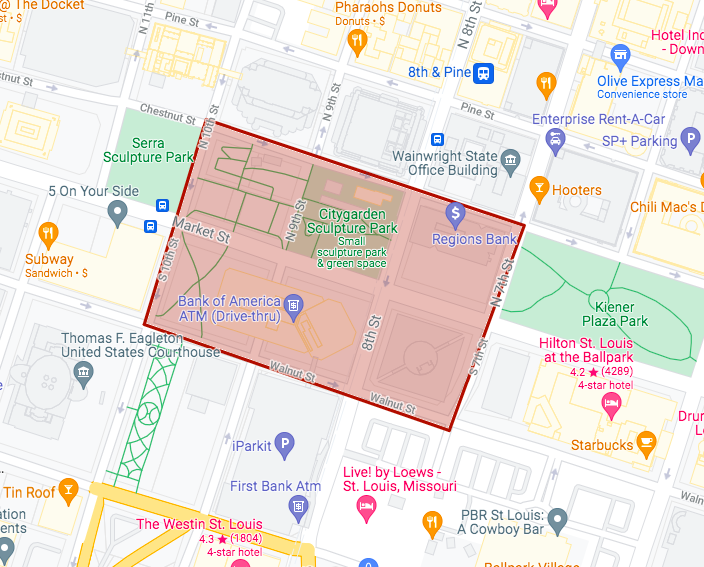

Chinatown or Hop Alley (literally an alley) was destroyed for a surface parking lot in the mid-1960’s, when it was considered undesirable by the white powers of the time. The destruction of Mill Creek Valley, parts of Downtown St. Louis and Kosciusko were all goals of the power structure of the time, most of whom had up and left St. Louis for the burgeoning small towns and suburbs in the County. “Slum clearance”, “Urban Renewal”, all phrases used to wipe history from the map and public consciousness.

The core of Chinatown and its concentration of businesses was primarily the area bound by 7th Street to the east, Market to the north, 8th street to the west and Walnut to the South, the block now occupied by the headquarters of Spire, the local natural gas utility. This building was originally built as the General American Life headquarters, designed by renowned architect, Philip Johnson. Additional Chinese businesses were scattered up to Chestnut to the north, 10th Street to the west and Walnut to the South, areas now occupied by the former Mike Shannon’s restaurant, Citygarden Sculpture park and other structures.

Places matter. People matter. Our stories and history matter. I was thrilled to learn about the Grandview’s past connection to Chinese-Americans.

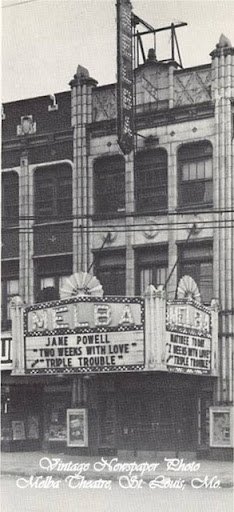

First, some information on the Grandview Arcade building and the Melba Theater from Peter’s research.

Per the St. Louis Star and Times (August, 1925), the three-story building, designed by architect George Soko, was completed around August, 1925. It is constructed entirely of reinforced concrete and was fireproof throughout, including the roof. It was described as Gothic design and the basement was designed for ten bowling alleys and pool tables in the basement. The 2nd floor had 14 shops and 30 offices. It was designed for doctors, dentists and real estate agents. The building cost was $550,000, $8.7M in 2022 dollars.

I described this as the Melba Theater building in previous stories and this is what most people called it back then. The Grandview Arcade name was not colloquially used as much, but was when tied to the offices, mainly loan officers, mortgage companies and accountants.

The Melba Theater was actually directly behind the Grandview Arcade. Is was originally a park-like open-air dome prior to central AC, and then a building of it’s own eventually with AC.

The first shows dated back to December 1st, 1917. The Melba was eventually owned and operated by Fred Wehrenberg and they leased the front entrance from the Grandview Arcade so people could enter off of Grand. Before the Grandview Arcade was constructed, you entered the Melba off of Miami Street.

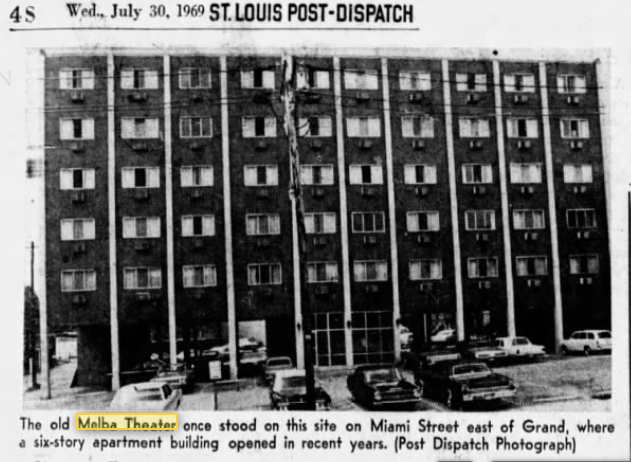

The Melba Theater once had a live orchestra and live performances before movies took hold. The Melba hosted dancers, comedians and singers. It was eventually destroyed in the 1960s for a “modern” high rise apartment building.

The 1960’s apartment building that replaced the Melba Theater still exists.

Below is a picture of the surface parking lot and apartment building from 1969.

The relevance of the theater to Peter?

As hardworking new business owners, Peter’s parents were working day and night, yet had two children (Peter’s brothers, Richard and David) aged 5 and 6. They all told the story of putting them in the theater to watch movies while they worked upstairs, regularly checking on them every 15 minutes or so. This story had always been confirmed by Peter’s brothers, but at age 5 & 6, they had no recollection of where this building existed, until recently.

Upon Peter’s recent visit to the building in November 2021, he brought his brother Richard with him to see if anything would jog his memories, nearly 65+ years later. Remarkably, standing in the arcade looking at the monumental staircase, Richard was projected back in time. Peter & Richard retraced Richard’s recollection on how he was taken from the office, the turns he made and time required to get down the stairs to the theater doorway. They were able to pinpoint the office suite where the Tao’s first office was located. The ‘tale’ was cemented in reality.

Left photo: The small 2-room office suite, conveniently located to scurry the Tao boys to the theater.

In addition to being William Tao’s first engineering offices in 1955, the building was the final home to Asia Food Products and the On Leong Merchants Association. Asia Food Products was the successor to Asia Cafe, which was literally the last restaurant standing in downtown Chinatown. When the Leong family had to relocate from downtown Chinatown, they had decided to give up the restaurant business and focus on the growing needs of Asian food products. St. Louis was changing.

Per the University of Missouri – St. Louis:

“The On Leong Merchants and Laborers Association was a fraternal society believed to have originated in San Francisco sometime during 1874. This organization offered a safe haven against the (sometimes violent) persecution Chinese immigrants received from the United States. In return for a small membership fee, the On Leong served the Chinese American community by aiding immigrants with 1) language and American customs/practices difficulties, 2) immigration policies, 3) business or personal matters and disputes and 4) the formation of new businesses/alliances.

On Leong, meaning “peaceful,” often set regulations to prevent competition and conflict between neighboring merchants. Established in St. Louis sometime after the turn of the century, the local chapter retained its Chinese heritage by complying with certain Chinese traditions. For example, women were not allowed into this fraternal society and the Chinese god of merchants, Gwan Gung, adorned the entrance of headquarters.

In the 1950s, the On Leong association, then located above the Asia Restaurant, still existed as an aiding organization for merchants and laborers within Chinatown (although it still excluded women as members). They negotiated with the officials of the Civic Center-Busch Memorial Stadium project on urban renewal issues. In addition to political support, this association acted as a heritage center for the local Chinese, and hosted the annual Chinese New Year celebration. Charles Quin Chu resided as the official “Mayor” of Chinatown.” (source)

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a story on Chinatown in 2020, which included quotes from Annie Leong:

“I was born in this building. It’s home and I don’t want to leave,” said Annie Leong, who ran the restaurant with her stepfather, Nin Young. “I think some of the older Chinese people will be lost when they are forced to move out.”

The Asia Cafe, at 722 Market Street, closed on August 1, 1965, to make way for the land-clearance project that created the first Busch Stadium downtown and related developments. The restaurant was the last business standing in the old district, once home to laundries, groceries, a few restaurants and many of the Chinese-Americans who worked in them. (source)

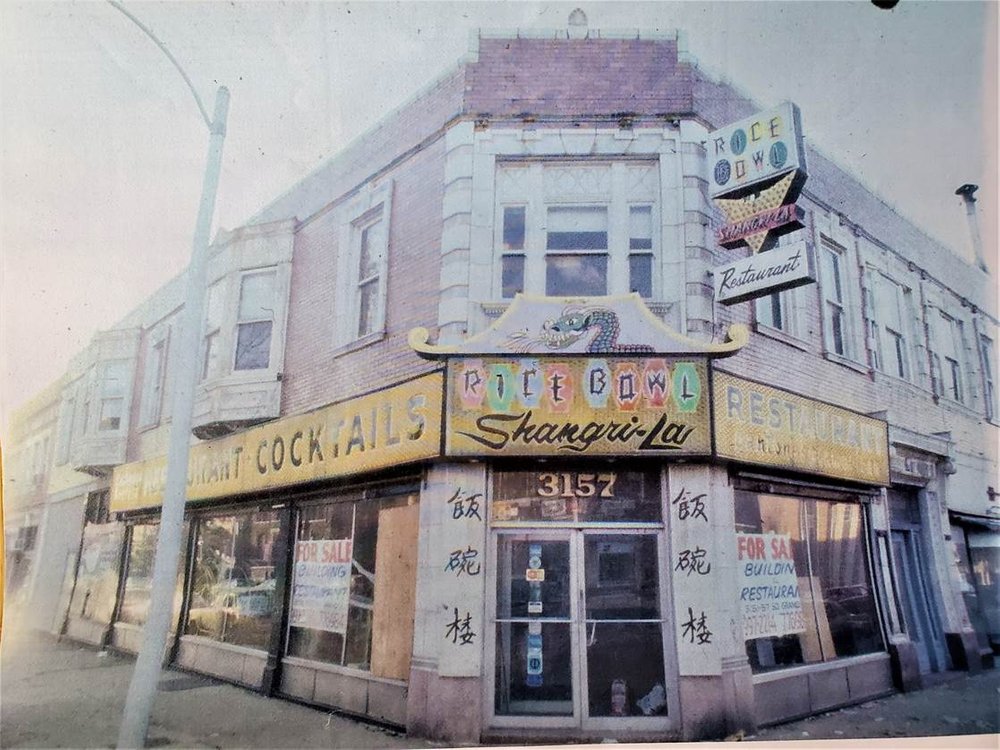

There are many other stories to tell about buildings and businesses along South Grand and South City, such as the building that currently houses the Thai restaurant “King and I,” formerly a Chinese restaurant called the Rice Bowl. Perhaps another chapter.

The current owner of the King & I building formerly worked at the Rice Bowl as a young student/immigrant.

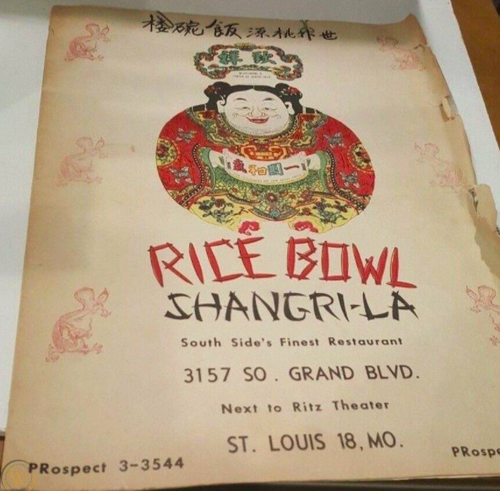

A Rice Bowl menu image from the 1960s confirms its location “Next to the Ritz Theater” which was destroyed by the Community Development Agency in 1986 for surface parking. (source)

Though there are so many local stories to be told, this blog will take a pause, since an exciting endeavor is currently happening with regards to finding history, in particular Chinese American History.

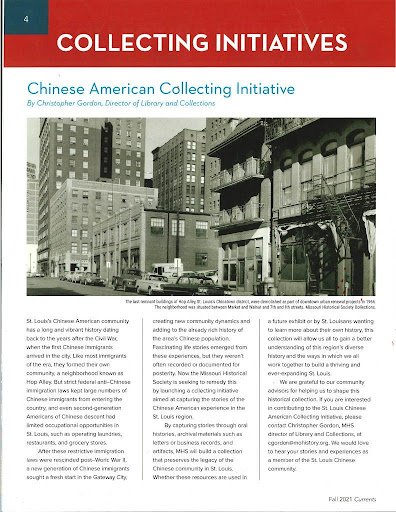

In 2017, Peter approached the Missouri Historical Society about the importance and the need to recognize the role of the Chinese Americans in St. Louis. With no hesitancy the MHS agreed that a permanent collection should be started. In 2021, the Collection Initiative efforts became public.

As a lead in to the St. Louis Chinese American Collecting Initiative, Peter collaborated with the Missouri Historical Society to present a story and share some history during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in a fascinating retelling of his family’s history, their paths to St. Louis and how they helped build, mentor and support the local Chinese-American community, eventually helping with the effort for local and national representation, with the founding St. Louis Chapter of the OCA/Organization of Chinese-Americans (now OCA-Asian Pacific American Advocates). Here is a link to the presentation.

Thanks to Peter for reaching out and sharing his story. I will have the history of Chinese-Americans in my mind when driving by Grand and Gravois. I will further celebrate this history as the Grandview Arcade, a 1920s architectural treasure, is brought back to life by Garcia Properties to new housing and retail.

Buildings have stories to tell. Saving this building has allowed people like Peter to discover, research and reveal that there are stories associated with this building to share with others. First, with the finding of his father’s 1960s building photo, this confirmed the verbal and written “tales” of the building.

All the best to Peter and his continuing research on the important role Chinese-Americans played in St. Louis.

Additional St. Louis Chinatown Resources:

St. Louis Post-Dispatch – Take a look at the last days of St. Louis’ Chinatown – August, 2013

Distilled History – Hop Alley & White Lightning – July, 2013

Missouri Historical Society – Dr. Huping Ling Video – June, 2020