On summer weekends, hundreds of recreational boaters motor around the islands and side channels of the Mississippi River near Dardenne Slough off St. Charles County, Missouri, some forty to fifty river miles north of St. Louis. Boaters can rent a slip from one of the twenty-one marinas along the Mississippi from St. Charles County to Alton, Illinois. Many marinas also run their own restaurants or bars, a place where members go to grab a drink with like-minded people, compare notes about boats and the river, and maybe meet their future spouse. Scenes like this play out all along the upper Mississippi River, where recreational boating is a common, if sometimes forgotten, part of river life and local economies, at least north of St. Louis.

Marina Life

Marinas play an important role in keeping the recreational boating economy humming along, and the Alton Marina is one example of how a marina can succeed on the Mississippi River. It opened about twenty years ago on land owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, but the structures are owned by the City of Alton. Alton, in turn, contracts with a private company, Parrot Pointe Marine, Inc., to manage it. The marina generates enough money to support its annual operations and routine maintenance, but the City of Alton sometimes helps with large capital expenses.

Boaters can rent one of the three hundred slips for a few days or a full year. Members also get access to amenities like a swimming pool and hot tubs, hot showers, and concierge services. (They’ll deliver food and supplies right to your boat.) Three dozen boats can tie up at the transient slips for part of a day. They fill up on summer weekends. Other marinas in the area offer similar services.

Boating on the Mississippi has some distinct advantages over boating on the region’s big lakes. For one thing, you don’t have to drive for two or more hours to reach your boat. Besides that, the Mississippi isn’t as crowded as the lakes, so if you own a smaller boat, you won’t risk getting swamped by the behemoths common at the Ozarks. Boaters that I talked with at the St. Louis Boat and Sports Show in 2019 also highlighted the river’s scenic beauty and opportunities to see wildlife. Long-time river enthusiast John Bloch said boating on the Mississippi River is more than just recreation. “I feel connected to the rest of the world,” he said.

The rivers in our region also attract a niche group of recreational boaters known as Loopers—leisure travelers who follow all or part of a six thousand-mile circular water route through the central and eastern U.S known as The Great Loop.

In our region, the route follows the Illinois River, then the Mississippi from Grafton to the Ohio River. Many Loopers regularly tie up in Alton for a few days to restock and rest. Some also use Alton as a base to explore St. Louis.

A Marina Desert

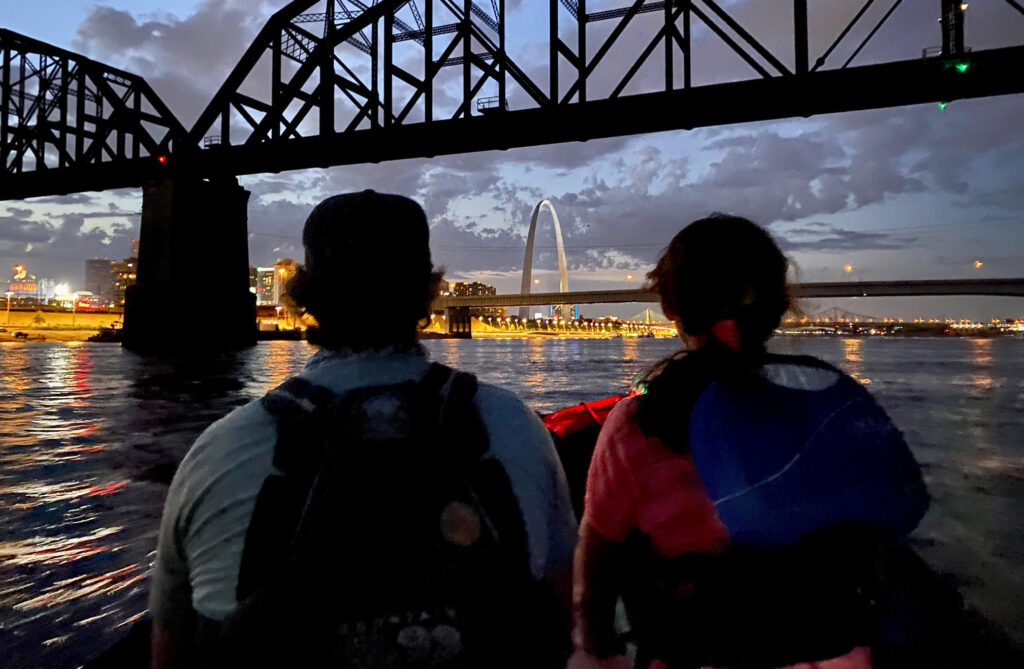

Downriver of Alton, the recreational economy on the Mississippi River is less robust. There are no marinas in St. Louis proper. Boaters occasionally tie up along the levee below the Arch or at the porte cochère that once served as the front door for the President Casino on the Admiral, but neither is secure and sometimes the river is too high or too low for them to remain accessible.

Without a marina in St. Louis, the next reliable stop south of Alton is Hoppie’s Marina, fourty-three miles away in Kimmswick, Missouri.

If you’re boating downriver of Kimmswick, plan well and good luck. The next marina isn’t until Mud Island at Memphis, a distance of three hundred seventy-three river miles. The Greenville Yacht Club is nearly two hundred river miles from Memphis, and after that there are no marinas until New Orleans—another four hundred fifty river miles. And when it comes to welcoming recreational boaters, New Orleans is just as disappointing as St. Louis. The long gaps between marinas are one reason that Loopers are advised to skip the lower Mississippi altogether, even though it has some of the river’s greatest cultural and historical attractions.

A few communities have had marinas in the past or have taken a hard look at building one. Boaters in Sainte Genevieve enjoyed a boat ramp and marina off Gabouri Creek for nearly thirteen years. While it didn’t rent slips, boaters could refuel and eat at the Eagle’s Nest restaurant. The marina closed in 2005 after a fire damaged the building.

Caruthersville, Missouri, considered building a marina several years ago. John Ferguson, Executive Director of the Pemiscot County Port Authority, said that the county studied the possibility and concluded that a marina wouldn’t be financially viable. The study suggested that Caruthersville didn’t appear to have the population base to support it and passing boaters wouldn’t generate enough revenue to make up the difference.

Cape Girardeau is a bigger market, but the river narrows and runs fast near town, and industry already occupies many of the best spots where a marina might locate. Still, Cape’s mayor recently initiated a study to determine the feasibility of adding transient docks to the riverfront.

A Challenging Environment

Ste. Genevieve’s harbor on Gabouri Creek faced a difficult future anyway, because the creek was filling in. Sediment washes in from the Mississippi and settles in the creek. Mayor Paul Hassler told the Ste. Genevieve Herald in 2017 that it could cost upwards of a million dollars to dredge Gabouri Creek deep enough to restore boating access.

Sedimentation is a constant problem for most marinas on the Mississippi. A couple of springs ago, the Alton Marina spent tens of thousands of dollars to dredge the main route into and out of the marina and around the fuel dock.

Fern Hopkins of Hoppie’s Marina emphasized that the Mississippi River can be a tough environment for marinas. The current is tricky and floating debris can accumulate, limiting access to the docks and creating potential hazards for boaters. In winter, ice floes can create similar challenges. It takes a vigilant manager to keep it all running.

Wide variations in river levels can also complicate marina construction—the Mississippi can rise and fall forty feet or more in a year at places like Vicksburg, Mississippi—but there are engineering options that can help. The Alton Marina, for example, is anchored to spud poles that are driven thirty to forty feet deep into the river bottom. The walkways and docks are fastened to those poles, so the marina rises and falls with the river.

During the pandemic, many marinas have seen a jump in business as people looked for new ways to enjoy outdoor activities close to home. Before the pandemic, marinas had been losing customers as competition for recreational dollars intensified, so the boost in new boaters is a hopeful sign.

Building Partnerships

Marina owners are doing more than just hoping that trends will change, though. “We’ve seen the writing on the wall. There used to be more boats than slips; now there’s more slips than boats,” Alton Harbormaster Greg Brown said. The Alton Marina coordinates with the Great Rivers & Routes Tourism Bureau in Alton to entice boaters to visit the city for a day.

Alton is an easy trip from many of the marinas on Dardenne Slough, just twenty-two miles from the Yacht Club of St. Louis, for example, which is near the middle of the slough. The marina at Grafton is even closer, just seven miles from the Yacht Club. Boaters can tie up at a transient slip at either marina and visit the restaurants and shops in town. Stephanie Tate, Marketing and Communications Director for the Alton-based Great Rivers & Routes Tourism Bureau, said the summer concerts at the Alton riverfront amphitheater draw a lot of boaters too, as do the city’s fireworks show on July 3.

The future of marinas and recreational boating on the Mississippi River will be even brighter if we can build more partnerships. Between the travel times and cost of fuel, many boat trips are relatively short, like that seven-mile trip from the Yacht Club to Grafton. If river towns banded together to close the long gaps between marinas, it would make recreational boating on the Mississippi more attractive and could bring more visitors to river towns.

We don’t need a chain of full-service marinas every twenty miles along the Missisisppi, though. A Hoppie’s-style marina might be the way to start in places like Caruthersville, Cape Girardeau, and downtown St. Louis. Strap a couple of barges together and create spaces for recreational boats to tie up. Outfit the barges with pumps for refueling. Add a store stocked with boating supplies and snacks and beverages. Start small and see how it goes. At downtown St. Louis, the porte cochère that used to serve the President Casino on the Admiral could be a suitable location for it. Run a ramp from the barges to land, and boaters would have quick access to Laclede’s Landing, the Arch, and downtown.

River towns could band together to advocate for some of the federal money that is flowing from Washington. The Corps of Engineers just secured nearly $800 million to expand one lock at Winfield, Missouri, so a million dollars to dredge a channel for a marina at Ste. Genevieve is cheap by comparison. Maybe federal money could be used for some of the initial capital costs to buy barges and convert them into marinas.

Today’s Mississippi River will pose some challenges for recreational boaters, but they aren’t insurmountable. The Port of St. Louis gets a lot of barge traffic and industrial docks line both sides of the river. When I was in Cincinnati this summer, though, I saw a busy downtown boat ramp where boaters put in to enjoy some time on the Ohio River. The Port of Cincinnati is just as busy as the Port of St. Louis. We can deal with it.

The Mississippi is everyone’s river, even in downtown St. Louis. Recreational boaters could provide a modest economic benefit to St. Louis. And seeing boats other than barges on the river might also help counter misplaced perceptions about how dangerous the Mississippi is and who belongs on it.

St. Louis is a river town and we can do better at connecting people to the big river that served as our lifeblood for generations. More recreational boaters on the Mississippi at St. Louis would be one way to do that.

Editor’s Note: This article is part one in a three-part series on the Mississippi River.