When a new development is proposed, it goes through a process of consideration. Depending on its scope and requirements, it can pass through committees ranging from the Preservation Board, the St. Louis Development Corporation, the Housing, Urban Development, and Zoning Committee, and more. Many neighborhoods also have their own process to evaluate developments. During these processes, the developer presents renderings, site plans, elevations, and other relevant information. Sometimes they ask for variances from a form-based code, or request tax incentives. They put their best foot forward, and they paint a rosy picture of their development and themselves. It is a one-sided presentation.

In St. Louis, we often focus on the details included in these presentations alone, weighing the project’s merits. We ask questions about the materials, egresses, number of parking spaces, and the possibility of first-floor retail. What we don’t often do, and fail to do on a consistent basis, is vet the developers behind the project. In a city where any development is often seen as a good thing, we’re willing to take developers at their word and believe that they have every incentive to build quality developments. We don’t consider their character, their business practices, or their history. That is where we continue to hurt ourselves. If decades of dealing with Paul McKee has taught us any lesson, it should be this: developers don’t always tell the truth, and not all development is good development.

A developer’s character and their business practices matter. Developments don’t exist in a vacuum. Context matters. Buildings can have outsized impacts on their surrounding environments well past their initial construction. The people behind the development matter just as much as the structures they build.

For example, let’s take a look at Lux Living, who have proposed two new projects in the 17th Ward, one at the site of the Optimist International building in the Central West End, and another along Kingshighway in Forest Park Southeast.

Lux Living is a relatively new brand but the brothers behind it, Victor Alston and Sidarth Chakraverty, have a long history in St. Louis. Their names are tied to nearly 100 different LLCs in the area, but most people will recognize the name of STL CityWide Properties, formerly Asprient Properties. If Asprient sounds familiar to you, it’s because it garnered a reputation as one of the worst property management companies in St. Louis.

In August 2016, the Riverfront Times published a longform cover article about the mass of angry tenants that Asprient left in its wake. According to that article, which goes into several detailed accounts of tenant’s experiences, the company engaged in several questionable practices like changing locks without notice, charging bogus fees, and withholding security deposits over fictional claims. The biggest complaint: lack of maintenance. This was starkly evident in May 2021 when one of Asprient’s buildings in the Central West End suffered a partial collapse. The displaced tenants said that the structure had been in disrepair for years.

Asprient is the subject of numerous small claims cases and a class action lawsuit alleging illegal behavior in relation to how the company handles security deposits. Missouri law states that security deposits may only be used to pay for late rent or damages, but Asprient included clauses in their lease agreements that took non-refundable administrative and inspection fees from tenant’s security deposits.

Alston and Chakraverty’s response to these pressures has not been to reform their practices. When Asprient became infamous, the company changed their name. In September 2016, Asprient became STL CityWide, the name they use today.

Now they have another name for their new construction projects. Lux Living, which was established in 2019, is Alston and Chakraverty’s development arm. New developments have been coming at an unusually fast pace, including the Chelsea (2021), Hudson (2021), SoHo (2021), McKenzie (2022), and the two proposals at the Optimist International site in the Central West End and the former Drury properties along Kingshighway in Forest Park Southeast. The Steelyard (2016) and Tribeca (2018) were also built by Alston and Chakraverty under the Asprient name, but they currently claim them under the Lux Living portfolio.

Lux Living also has two proposed projects that are moving forward in Kansas City: the Edison at the former Faultless Linen site and their proposal for the historic Katz Drug Store. For those counting, that’s eight projects that are slated to begin or finish construction in 2021 and 2022, six in St. Louis and two in Kansas City. Such a torrid rate of construction leaves little time for us to know if their newest buildings have the same issues as the rest of the properties owned by their companies, but we have some clues.

Online reviews of the new Lux Living buildings that have recently completed construction are not much better than those garnered by historic buildings under the management of Asprient and CityWide. Common themes for these brand new buildings include: piles of trash in the hallways, ongoing security issues, tech problems with the electronic keys that leave residents locked out of their own home, heating/cooling issues, broken elevators, and pests like roaches and mice. Current and former residents lament that amenities boastfully advertised by Lux are often available only during the first few opening months, but become unavailable or are removed over time. Multiple reviews complain that the gyms often lack proper cleaning supplies, and the provided internet is undependable, often slow, but also mandatory to use.

Even if you can forgive poor management and a subpar living experience, St. Louis should be interested in building quality. As mentioned, many of Lux Living’s new buildings are still under construction, but there is enough information from the Tribeca and Steelyard buildings to see some trends. Tenants report flooding from adjacent apartments, non-functioning outlets, ineffective or absent soundproofing, doors and windows that don’t fully open or close, gaps between the rails and walls on the patios, cabinetry that falls apart, poor ventilation, and single-paned windows that leak when it rains.

In this case, vetting a developer by looking at their previous projects would be beneficial to the City. If this is the quality of the buildings when they are new, what does their future look like after time and a lack of maintenance take their toll? The city should not accept new apartments regardless of the quality. When the property tax value is contested due to depreciation, the assumption cannot be that rental rates will be lowered as the building ages. Has anyone ever seen a landlord lower their rents when it’s time to renew your lease with them? Older buildings are not cheaper to maintain, especially if they weren’t built well in the first place.

This is the kind of thing that St. Louis should be evaluating when looking at a proposed project. How will new buildings age? What will they contribute ten, twenty years from now when the flashy technology is outdated or irrelevant and the amenities are no longer a selling point? The apartments are “luxury” now, but we can’t assume that will trickle down to become affordable housing in the future.

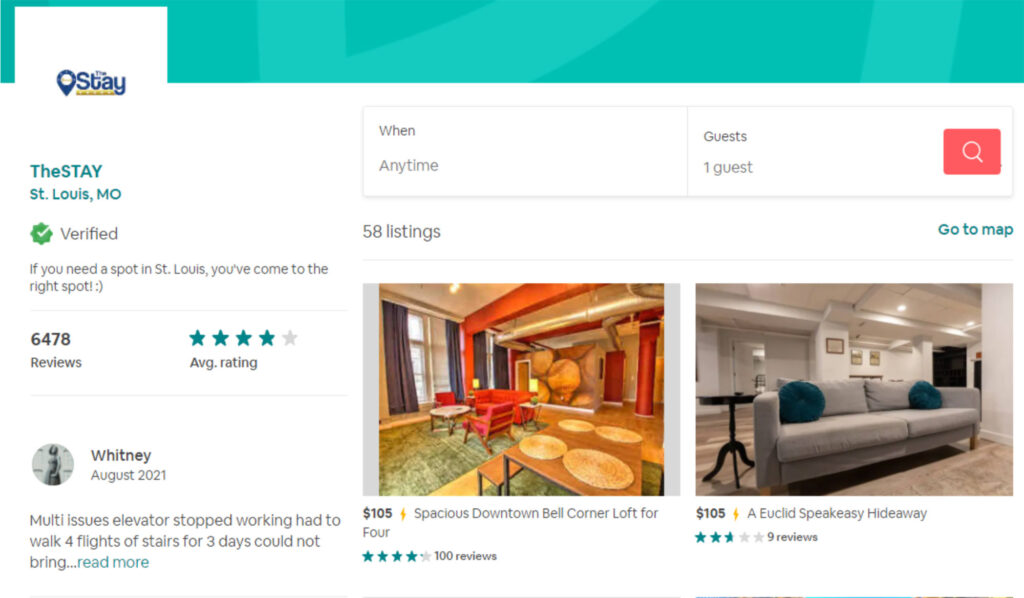

It’s not just poor maintenance and poor building quality. Lux Living quietly has another business on the side that also serves as a detriment to the City. One of the biggest recurring issues raised online, in both positive and negative reviews, is short-term rentals. Many of their apartments are rented out using Airbnb under the user profile, TheSTAY. Tenants object to the pervasive presence of designated Airbnb units, sometimes numbering in the dozens in one individual building. Parking becomes an issue as the building cannot accommodate the needs of Airbnb guests, then on-street parking becomes overwhelmed as well, affecting the surrounding neighborhood. Former tenants allege that short-term renters abuse or overrun the amenities and routinely violate the building rules without consequence from management staff.

Given the frequent mention of Airbnb in the reviews, it is clear that this is part of Alston and Chakraverty’s business model. Lux Living’s buildings were not pitched to the City as short-term rentals. Airbnb’s, while not illegal, are taxed at a commercial rate instead of a residential rate, but the City has not confirmed that they are even aware that these apartments are being used as de-facto hotels.

The City is, however, spending resources on policing these properties. Back in May, a viral video showed partygoers dancing atop and badly damaging a St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department vehicle after police broke up a rooftop party at the Ely Walker Lofts, a building partially owned and rented by STL CityWide. Again, we see a drain on City resources and an impact on the surrounding community.

The City of St. Louis has also been the victim on the front end of these developments. With the Steelyard, Soho, Tribeca, Hudson, and Chelsea, Alston and Chakraverty sought and received various tax abatements ranging from 80-100% for ten, sometimes twenty years. For Steelyard and Chelsea, Lux Living received additional tax-abatement on tens of millions of dollars in construction costs for the developments. But shortly after completing the Steelyard, Icehouse, and Tribeca, Alston and Chakraverty turned around and sold the buildings for substantially more than their stated construction costs. The tax-abatement was passed on to the purchasers: out-of-state private equity firms. These sales prompted St. Louis City to create a new clawback policy for tax incentives to prevent Lux Living and other developers from abusing the tax incentive system in the future. In these instances, not only did the City of St. Louis help a developer pad their pockets, but the City is also stuck with buildings owned and operated by out-of-state investors.

Even other developments have been hampered by Lux Living. In 2020, Vic Alston and Sid Chakraverty engaged in a legal battle with the developers of a rival development, The Expo, in the Skinker DeBaliviere neighborhood. Lux Living was in the process of seeking approval for tax abatement for their project, The Hudson, at 310 DeBaliviere Ave, when they used their attorney to revive a neighborhood association that had been dormant since 1990. Using the neighborhood association as a front, Lux Living claimed to have review rights for the proposed site of the Expo. Pearl Capital Management, The Expo’s developer, argued that Lux Living was simply trying to block or delay their development, which was a competitor to The Hudson. Lux’s plan backfired; their own tax abatement is currently held up over the dispute. The Expo broke ground anyway in October 2020, despite Alston and Chakraverty’s efforts to get the City to intervene. Now, Lux Living is suing SLDC, claiming that their project’s tax incentives are being delayed unfairly. The Expo, for reasons that are not yet clear, has halted construction.

Again, the City should be asking itself: is it worth doing business with developers like Victor Alston and Sidarth Chakraverty? What happens when developers try to actively thwart other developments in St. Louis for their own benefit? The City does not benefit from these conflicts. Our neighborhoods don’t benefit from overflowing parking, unruly Airbnb’s, or stalled developments over frivolous legal battles.

There are some, however, who do benefit from Lux Living’s actions, and that’s worth talking about too, because it’s not who should be benefiting. Like many developers, Alston and Chakraverty have donated to aldermanic and mayoral candidates in recent years, but they donate exclusively to politicians who have influence over their projects, and only when those projects are about to be up for consideration. This takes the appearance of a quid pro quo, and casts doubt on the entire political process.

Since 2014, Alston and Chakraverty have donated over $60,000 into the campaigns of local politicians. In 2016, they gave $3,000 to Lyda Krewson, who was 28th Ward Alderwoman when the City was considering tax incentives for the Chelsea, located in the 28th Ward. In 2017, they gave $10,000 to Frank Williamson, who was 26th Ward Alderman when they were pursuing tax abatement for the Tanjiers Apartments. In 2019, they gave $2,000 to Shameem Clark Hubbard, 26th Ward Alderwoman, who pushed the tax abatement for the Hudson forward over the objections of 28th Ward Alderwoman Heather Navarro, who has not been the recipient of their political donations. The Hudson sits right on the edge of the 26th and 28th Wards.

In the last election, Lux Living aimed $10,000 at current Board of Alderman president and then mayoral candidate, Lewis Reed. Aldermanic candidate Michelle Sherod received $5,000, but narrowly lost election in the 17th Ward, where two of Lux’s proposals are pending.

The biggest recipient of their largesse has been 7th Ward Alderman, Jack Coatar. Between 2020 and 2021, Alston and Chakraverty gave Coatar a total of $15,000 through multiple different LLC’s. Lux Living’s Steelyard and Soho projects, both located in the 7th Ward, received massive tax abatements while Coatar has been in office. Coatar also holds influential seats on the Preservation Board and the HUDZ Committee, and recently voted in favor of Lux Living’s request to demolish the Optimist International building to make way for their newest proposal.

Vetting developers would give the public key information to keep our politics and processes clean. Politicians who have received donations from individuals like Alston and Chakraverty would have the chance to show they have no conflict of interest or recuse themselves to avoid the conflict altogether. At some point in the future, some politicians might refuse donations from developers who have upcoming projects in their ward, knowing that the information would be made public. Either way, it’s beneficial for the public to have this information.

It should be clear why we need to vet developers in St. Louis. With this kind of information, all of which is publicly available, we have the tools to anticipate future problems and fix the proposals in front of us. Quality developers should welcome this, as their work and reputation will benefit them. We know that there are developers who take pride in their work. They build structures to stand the test of time and offer quality housing for the owners or tenants. There are also developers who build to meet a certain standard and make a good return on their investment. They may not build architectural gems, but they have standards and stick to them. These buildings have a role to play in our city, and we should welcome them when appropriate. But we should be wary of a third kind of developer whose main goal is to make money for themselves. Resident experience, tenant’s rights, and the building’s quality are of no consequence. These developers aim to fool and swindle. Vic Alston and Sid Chakraverty have the characteristics of this last kind of developer. Whether they build something new or take over the ownership of old buildings, their record is poor construction, bad management, lack of maintenance, shady dealings, and corrupt practices. No matter which name they go by – Asprient, CityWide, Lux Living – it is the same two people behind it all.

The City of St. Louis has been burned repeatedly by these brothers, but so far, no one in the City government has taken the time to look into their record or their credibility. When they stand in front of neighborhood groups, City boards, and committees, they tell us a story. If we don’t do our homework, we will be in a worse negotiating position, and we will end up in bad deals. But if we do our due diligence, we can hold bad developers accountable and encourage good development through the use of legislative tools and a rigorous vetting process. St. Louis should vet developers, and we should start now.