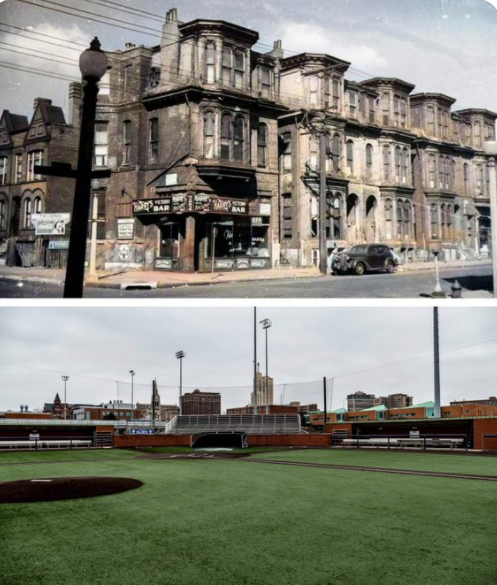

Downtown St. Louis is, at once, both the region’s greatest and most underutilized asset. It has weathered a violent century. The removal of downtown adjacent neighborhoods was catastrophic to the city’s core health. The old riverfront, decorated with cast iron facades, was raised beginning in the 1930s. Just north, Carr Square, home to generations of immigrants and beautiful homes one might find today in Lafayette Square, was leveled around the same time citing overcrowding and health concerns as the city’s lung block. On the western edge of downtown, Mill Creek Valley was the single largest urban clearance project in the country, tearing down mansions, charming rowhouses, a thousand businesses, and displacing 20,000 mostly Black residents. To the south, the Kosciusko neighborhood met the same fate. Deep Morgan and Chestnut valley, too.

In a span of roughly 25 years, a city core that rivaled the great American cities of the time was hollowed out. This, of course, was happening in other cities, too. But St. Louis arguably had it worse than any other city in the country. Downtown St. Louis boosters had advocated for this large scale clearance.

As Walter Johnson notes in his book The Broken Heart of America, the destruction of perfectly good buildings in the name of progress meant a reduction in housing and commercial supply. Rent Seekers saw this as imperative to prop up profit margins. Additionally, boosters also viewed – along racial and class lines – the neighborhoods surrounding downtown as being slums that reduced the desirability of business to operate there. In the end, Downtown St. Louis boosters were left with expanses of vacant land around their aging downtown, a reality that cripples St. Louis to this day.

@rrconstructor on Instagram

A Broken Promise

Today, St. Louis residents are disconnected from their downtown. on the riverfront, the Gateway National Park sits lush and green, but with just the Old Cathedral as a reminder of what once was. To the north, Carr Square and Columbus Square provide affordable housing at a reasonable density, but are nothing compared to what was once there. Moreover, these neighborhoods lack sufficient commercial offerings and are largely low income. However, there is a federal grant for Carr Square to develop a more mixed-use and mixed-income neighborhood. Additionally, Columbus Square has room for infill to realize a similar future. Old North does already capture the spirit, though, and is a shining example of grassroots success.

To the south, Peabody Darst-Webbe shares a similar narrative while the area south of Busch Stadium serves as little more than overflow parking for the baseball club on gamedays. Lasalle Park sits like an island, cut off from Soulard by the freeway, yet architecturally distinct from its nearby neighbors considering its aged brick. Kosciusko never met the promise made by the wrecking ball when only 1.6% of the projected redevelopment occurred. Today, it is a disappointment of an industrial park. Soulard was spared and Lafayette Square, too. However, their rarity in the wake of malevolent renewal has meant that these neighborhoods have become some of the more expensive places to live in St. Louis. Increasingly, affordability slips away.

To the west, Mill Creek Valley has become a highway, sports fields for two colleges, and a Wells Fargo Advisors HQ. No one really lives there anymore, and it shows. Jeff Vanderlou (JVL) is perhaps the best reminder of what Mill Creek Valley once was as 19th century development didn’t care for the Delmar divide. Still, JVL is a long neglected neighborhood that badly needs equitable investment to be saved before it is too late.

The neighborhoods surrounding downtown were leveled with the promise of renewal. this promise was at best a foolish thought experiment and at worst a violent campaign.

A Path Forward

A large part of the reason that downtown feels underutilized is that the city removed so many of the communities that were within a short walk. Rebuilding those communities adjacent to downtown can help to turn the tide. To do that, civic leaders must get creative to incentivize immediate low-rise development around downtown.

Housing Types

First, it is important to understand what that type of development should look like. Consider current demand. Rowhouses, Stacked rowhouses, and the ubiquitous 21st century five-over-one should erupt around downtown. A new high-rise signals growth and prosperity to out-of-towners, but a consistent and vibrant street wall is more important. In a city like St. Louis, which has been a slow growth region for decades now, one must choose. Every 30 story tower eats the demand of six five-over-ones. Until the city sees consistent demand for high-rise buildings, it should focus its efforts on low-rise buildings to fill in the many vacant lots.

The rowhouse and stacked rowhouse both offer a housing type that is rare around downtown these days. A more popular option for families that maintains relatively high density, the rowhouse has a valuable place in the downtown adjacent built environment. These renderings from Killeen Studio Architects would be a welcome addition to any of the neighborhoods around downtown. Instead of parking lots south of Busch Stadium, imagine a neighborhood filled with these homes.

To keep the feel of rowhouses while adding more people, the stacked rowhouse offers twice the density. Essentially it is a rowhouse, but with two units. One on the top two floors and the other on the lower two floors. Again, this is a missing housing type around downtown that might be very appealing to folks that do not necessarily want to live in a large condo building.

In addition to rapid rowhouse construction, nearly every single corner lot should have a five-over-one building. These developments at ground floor retail, offer commercial space on upper floors, and greatly increase density. Remember, for every AT&T sized High-Rise (44 stories), you could have nine of these buildings. Which do you think would have a greater impact on the vibrancy of downtown?

Unproductive Land Use

None of this housing can be built, though, if the city continues to allow surface parking to be the focus of downtown real estate. Dense housing and surface parking are natural enemies in the sense that this town ain’t big enough for the two of ’em. With current property tax laws, it greatly benefits a speculator to landbank downtown adjacent parcels by turning them into surface parking lots that generate just enough revenue to pay the property taxes. Perhaps a Transit Development District that taxes vacant and surface lots in the area could both spur the development of those lots by making them an unproductive and costly burden while also funding a downtown (and adjacent) circulator streetcar like our neighbors in Kansas City. Whatever the solution, surface parking and vacant downtown adjacent land need to disappear in favor of houses for people.

An Unmet Demand

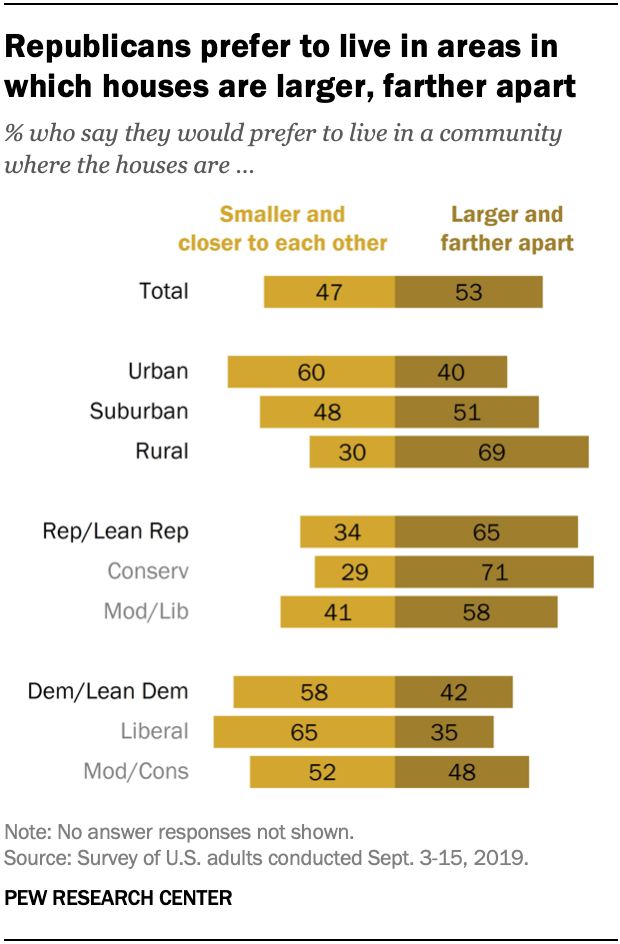

Forty-seven percent of Americans want to live in the types of dense walkable neighborhoods that our downtown adjacent neighborhoods can be. If we assume this number is roughly the same in the St. Louis Metro Area, we are doing a dismal job at meeting the needs of our citizens. This means that demand exists, and we should encourage developers to rise and meet those needs. There is a reason that Soulard, Lafayette Square, and co. have become increasingly expensive. The demand is there. Build more supply.

Low-Rise Now, High-Rise Later

Growth is often gradual. To demand that every vacant parcel near downtown become a mid or high-rise betrays conventional wisdom of basic economics. If in the boomtown of the late 19th and early 20th century St. Louis was still mass producing rowhouses and other low-rise housing types near downtown, there is little excuse for the St. Louis of today to do more than that. Build out the area with low-rise construction first, and as the energy returns, the demand will quickly justify certain parcels being torn down and replaced with taller buildings.

At Downtown’s Edge

St. Louis is on the verge of a renaissance, but it cannot achieve that without a healthy downtown core. And it cannot achieve a healthy downtown core without vibrant, bustling, and growing neighborhoods at its edges. Downtown adjacent development isn’t just another housing development, its an economic stimulus.