Last week, owners of certain properties in the city’s JeffVanderLou may have been surprised that a brochure circulated offering opportunities to lease their properties – except not their actual properties, their properties bulldozed after taken by someone else.

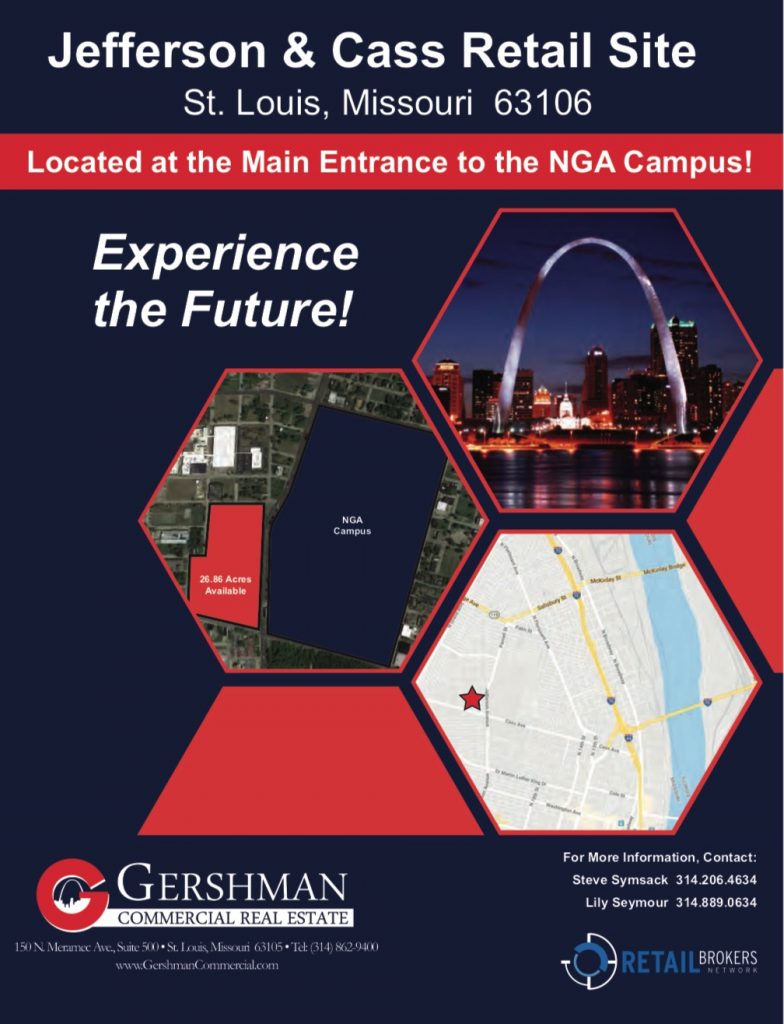

Gershman Commercial Real Estate circulated a pitch to lease space in the “Jefferson and Cass Retail Area” – space that it promises will be owned by Northside Regeneration LLC by the time anyone writes a lease. The brochure shows a 26.28 acre site at the northwest corner of Cass and Jefferson avenues immediately west of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency site as an available opportunity for retail. Currently, the site is a multi-block area of the neighborhood including many residential buildings, a church and other buildings. The western end consists of a line of contributing resources to the Yeatman Square Historic District, a National Register of Historic Places district.

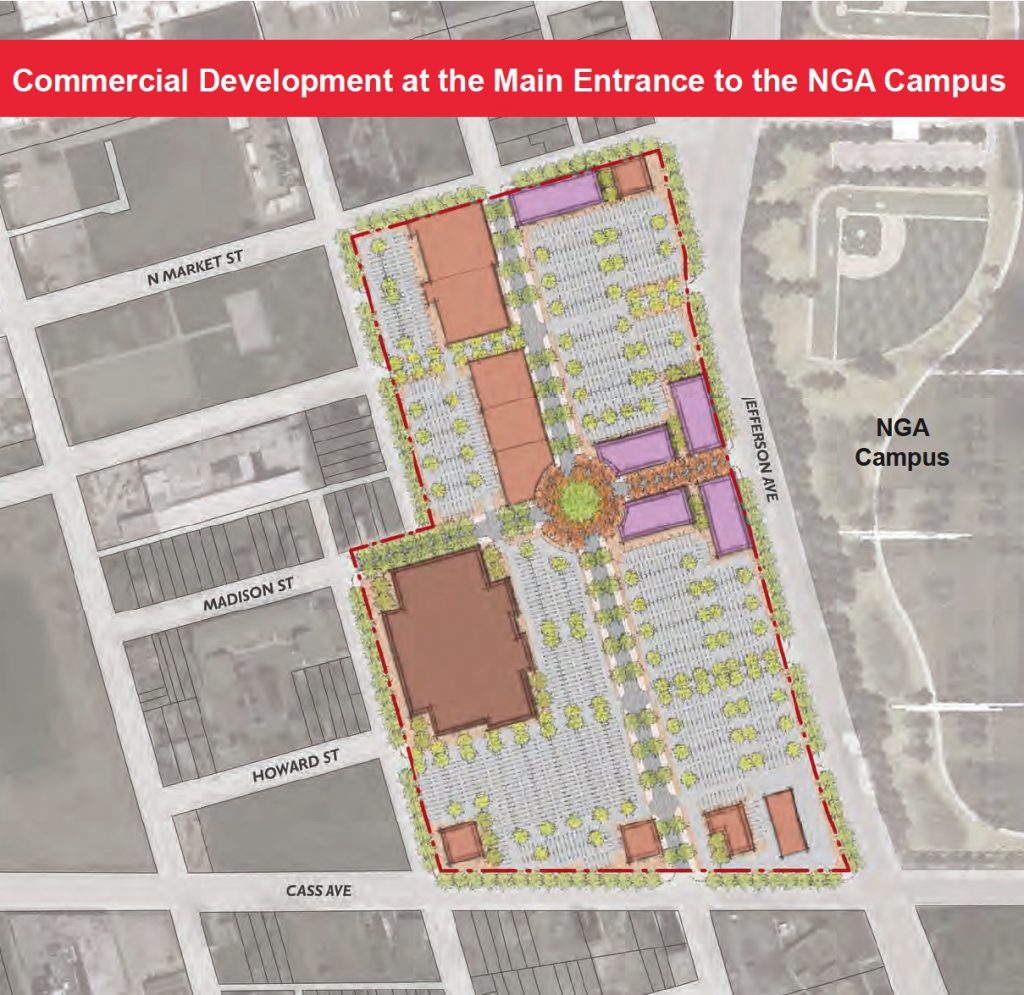

To date, the Board of Aldermen has neither approved nor considered any legislation that would enable Northside Regeneration to building the retail development as depicted in a generic suburban-style parking-lot-oriented superblock form. Street closures would require legislation. The land use would require zoning changes for some of the land. And the use of eminent domain to acquire any properties in the area has not been authorized.

Northside Regeneration did indicate that the release of the brochure was premature in comments to Jacob Barker of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, but the plan shows an intent to deviate from land uses and building forms first proposed by the developer in 2009, which remain the only redevelopment plans authorized for the site.

Even those redevelopment rights are on ice, since the City of St. Louis continues to nullify its redevelopment agreement with Northside Regeneration. City Counselor Julian Bush first notified Northside Regeneration LLC of the city’s intent in a letter dated June 8, 2018. Then, Bush stated that the city considered Northside Regeneration in violation of the schedule of construction deadlines established by the 2009 redevelopment plan and modified in several ensuing ordinances. The original agreement had a 30-year timeline for building $8 billion worth of real estate development. Nearly ten years in, Northside Regeneration has completed one gas station and is about to complete a small grocery store. Furthermore, according to Bush’s letter, Northside Regeneration owed the city $273,000 in unpaid real property taxes in 2018. Bush gave the company 30 days to comply with stipulations, but the matter has ended up in court.

Thus, the ability of Northside Regeneration to seize upon any interest in land adjacent to NGA is, for the first time since 2009, ambiguous. Even if the Board of Aldermen, which has generally gone along for McKee’s ride every step of the way, tried to pass enabling legislation for the retail project, Mayor Lyda Krewson would likely veto it as long as the city seeks nullification of the redevelopment agreement. Eminent domain, thankfully, seems very far-fetched at long last.

Should the city and Northside Regeneration come to terms for some reason, the retail plan shows a major deviation from McKee’s initial promise to develop this area with a mix of historic rehabilitations (the sad state of most of these documented recently by Landmarks Association of St. Louis) and mixed-use buildings set along the major streets. McKee and his planning firm Civitas spun a vision of resilient, dense urbanism, replete with a new trolley, a Jefferson Avenue lined with multi-story buildings with street-level retail and space for 22,000 permanent new jobs.

The big-box and outlet rendering in Gershman’s brochure shows a pretty long fall from vision, and the continuation of unequal substitution in Northside Regeneration’s plan. The company earlier promised a robust residential infill program where the NGA would be built. The difference between a complex, high-density and diverse urban neighborhood and retail and office superblocks is stark, although perhaps the smartest short-term strategy for capturing surplus value.

The proposed layout of the project makes one think of how to locate the exact difference between locating the NGA here and locating it in Shiloh, Illinois. The site places just 13 buildings on over 26 acres, by the way – two buildings per acre. No apartments and new residents are proposed, nor are any other attributes of a neighborhood. This is a drive-by strip destined to subtract money — seemingly the impending discretionary income of NGA employees — not give it back to the community. In fact, its existence requires removing part of the community. (This story’s getting old, St. Louis.)

In fact the bland and typological layout of the development recalls the lines of retail strips located toward Scott Air Force Base in Shiloh – open parking area facing a main road, low density site planning and nothing memorable in design. These sorts of developments are just compartments for exhausting surplus valuation. Someday, the Office Depot becomes a Family Dollar or Granger. The Panera becomes a Cici’s Pizza. No one remembers the airbrushed renderings – or the balance sheets submitted to city councils – then. No one tries to remember anything in such a place. They exude an amnesiac America – a United States of Whatever.

Yet there is a supposed difference here – the retention of earnings-tax-paying jobs in the city. That promise has been eagerly discarded by regional leaders now backing a Better Together scheme that erases the earnings tax except as an IV drip for the city’s debt service. If Better Together goes through, the destruction of this part of north city as an urban place was not worth anything. Literally this could have gone to Shiloh and looked exactly the same, while north St. Louis could have regenerated in the manner that McKee swore he supported back in 2009. If Better Together dies, then, the NGA may look like it was worth it, if it fulfills the promise that it was leverage to enhance the surrounding area through prosperity for existing residents and the kind of urban design that would make young urban skilled workers dream of working at NGA.

Either way, north St. Louis deserves the same attention to urban design, density and respect for the value of current inhabitants that one is seeing across the central corridor and south St. Louis. How come everything that poses as additive in north city for the last half century has actually been subtractive instead? Fewer buildings, fewer residents, fewer jobs, fewer taxes collected. Look at the strip mall plan superimposed over what exists there now, and one sees that the result will be less, not more, for north St. Louis.