It’s official: A task force sponsored by local think tank Better Together is calling for the City of St. Louis and St. Louis County to combine in a new type of local government called a “Metropolitan City.” Governed by an elected mayor and a 33-member council, the new Metro City would have sweeping powers to enact new laws, tax its residents and oversee functions including the police, courts and economic development.

Because the proposed changes would require amending Missouri’s constitution, Better Together will seek an initiative petition to put its proposal on a statewide ballot in November 2020. If approved, a two-year transition period would begin in 2021, with the new government fully in place by 2023.

The task force’s plan is ambitious and complex. It already faces opposition from the Municipal League of Metro St. Louis and others who oppose a statewide vote and worry about forfeiting local control. Adding further spice to the mix is the behind-the-scenes role of philanthropist and political donor Rex Sinquefield, a champion of limited government who is Better Together’s main financial backer. He’s expected to help bankroll a $25 million statewide campaign to convince voters to support the proposal. (Better Together insiders acknowledge that a statewide vote, rather than a vote only in the city and county, would probably be easier for them to win.)

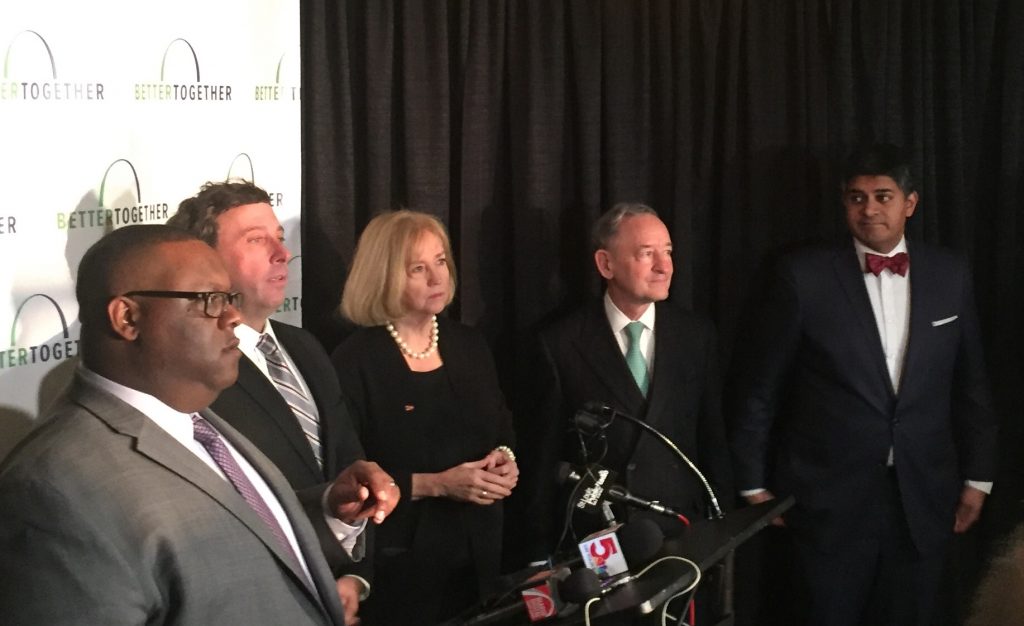

Here are five takeaways after Better Together’s formal announcement of its proposal on Monday. They touch on themes certain to surface as the ballot campaign, led by outgoing Washington University Chancellor Mark Wrighton, gets underway.

1. Will St. Louis Metro City really be the nation’s 10th biggest city? Or merely the 30th? Keep an eye on the Census Bureau.

Bragging rights matter, so the bureau’s eventual determination will be important. Better Together plans to reclassify existing cities in St. Louis County as “municipal districts” with limited taxing and lawmaking powers. Legally they would no longer be fully-fledged municipalities. Better Together’s lawyers say this means their residents would be counted as residents of the Metro, not of a particular muni district. Chesterfield, for example, would no longer have around 47,000 residents, at least for census purposes. It would have zero.

If the Census Bureau agrees, it means the population of the Metro City will be around 1.3 million, which is good enough for 10th place based on 2017 figures (behind Dallas and ahead of San Jose). But if the Census Bureau decides to keep counting Chesterfield’s residents as part of Chesterfield, and does the same for Florissant, Kirkwood and every other county municipality, it would reduce the Metro City to a “balance population” of around 615,000.

This would put St. Louis at No. 30, right behind the “balance population” of the consolidated Louisville Metro (621,000), where many suburbs have continued as incorporated municipalities (each with its own Census population) following a city-county merger in 2003. Coincidentally, St. Louis would be just ahead of Baltimore (612,000), the only independent city in the U.S. besides the current City of St. Louis.

2. Both proponents and opponents of Better Together’s plan can claim a piece of moral high ground.

From the outset of its work in 2013, Better Together has sought to inspire the public by speaking in optimistic terms about its goals for a stronger, more unified and more equitable St. Louis. No person captured this sentiment better at Monday’s announcement than Arindam Kar, a partner at the Bryan Cave law firm who served on the task force. “There is a real human cost to the splintered system we have created,” he told the audience. “Fixing it won’t be easy, but the alternative – to do nothing while people suffer – is simply unacceptable.”

Messages like these complement the “Reimagine STL” theme that Better Together is emphasizing in its unsubtle appeals to local pride. “Imagine a world-class city we can all be proud to call home that competes on a national and an international stage,” the task force’s report says. “Imagine a safer, more prosperous, more secure city that takes care of everyone equitably and where everyone has the opportunity to achieve.”

The Municipal League has had less time and fewer people to marshal its forces, so it has no lofty rhetoric. But the League’s executive director, Pat Kelly, has made it clear that his organization opposes a statewide vote. State Sen. Jamilah Nasheed (D-St. Louis) also opposes it. Their point is simple and compelling: Local voters should be able to determine their own type of government, instead of being dictated to by outsiders. This argument carries moral weight of its own, and it means that if Better Together’s plan is implemented, many St. Louisans will consider it legitimate only if it wins approval from a majority of voters in both the city and county.

3. In situations where inspiration fails, both sides have another tool at hand: fear.

Better Together’s proposal is certainly high-minded, but like earlier reports released by the Ferguson Commission and Washington University’s For The Sake Of All project (now Health Equity Works), it also resorts to brutal honesty. In some places the tone of the task force’s report is nothing short of menacing, as in this warning: “The status quo is a recipe for stagnation, decline, and widening disparities within our region.”

Taken to its extreme, the argument boils down to the following: St. Louis, you’re drinking in the last-chance saloon. Your young people are fleeing in droves and you can’t pay your bills. If you don’t fix yourself now, you’re going to shrivel up and die.

This message is designed to get people’s attention, and it helps explain why Better Together and its backers have rejected incrementalism in favor of wholesale reform that would effectively abolish the government of the city of St. Louis.

But the whiff of ruthlessness that has long surrounded Sinquefield now surrounds Better Together by association, fairly or unfairly. This will make it easier for opponents to take their own arguments to the extreme. In African-American areas and in the gentrifying neighborhoods of St. Louis’s South Side, the messages could run as follows: If you vote for this, there will be hardly anyone in power who looks out for your interests, or shares your values. The message to voters in Kansas City, Springfield, Columbia and elsewhere could be: If you vote for this, first they’ll come for St. Louis. Then sooner or later, they’ll come for you.

The Municipal League’s Kelly already issued his own warning to county residents in an interview with McPherson in December: “If this is successful, then what’s going to stop people from doing an initiative petition to consolidate school districts?”

4. More specifics from Better Together about how the Metro City would deliver services and allocate its citizens’ tax dollars will be key to its success.

The path to an election victory on Nov. 3, 2020 is akin to walking a tightrope. On one hand, Better Together must convince enough voters that a Metro government would be a more equitable and reliable provider of police protection and other services than the current patchwork of governments, particularly in north St. Louis County. At the same time Better Together must persuade enough residents of all stripes – but particularly conservative-leaning residents of central, south and west St. Louis County – that it will deliver on its core promise of massive government cost savings.

If talk of cost savings sounds similar to the bold promises of “synergies” that accompany corporate merger announcements, that’s because it is. From its inception Better Together has been transparent regarding the fact that its work is not only about civic ideals, but about tax dollars and where they might be saved. The organization knows that if enough voters believe Metro City is simply a mechanism for siphoning their tax money to bail out the City of St. Louis or a distant suburb without being accountable for how that money is spent, its prospects are sunk.

The figures Better Together offers up are impressive: an eventual operating surplus for the combined Metro City of around $250 million a year, even with an initial property tax that’s lower than the current St. Louis County rate. To put $250 million in perspective, it’s about half the size of the City of St. Louis’s main operating fund. Better Together says the new Metro City could gradually phase out the present city’s 1% earnings tax and still use the proceeds to pay off the city’s roughly $700 million in debt, including pension liabilities, over seven years.

Even if these projections are too rosy, they underscore what a hopeless financial enterprise the present City of St. Louis has become. At present the city barely manages to pay its bills, even with $175 million in earnings tax receipts each year. So Better Together’s plan could be an enticing carrot for voters across the metro area, since all who live in the city or work there pay the earnings tax. (The Municipal League has research of its own that casts doubt on Better Together’s figures, however, so expect a fierce battle over whose math is more credible.)

5. A winning statewide coalition of voters for Better Together could take many forms.

Missouri’s rightward drift in recent decades has been well-documented. On a per-capita basis it has fewer immigrants, Latinos and Asian-Americans than faster-growing states, and its population skews older. But the state reflects the diversity of the U.S. in important respects. Its racial balance between black and white is largely in step with the national average. St. Louis and its surrounding counties remain heavily Catholic. The state’s unions are still forces to be reckoned with; last August voters rejected a “right-to-work” law, and in November they approved raising the state’s minimum wage. University towns like Columbia and Springfield are blue-ish pools in a sea of outstate red. And Missouri elected its first Jewish governor in 2016.

Against this backdrop, Better Together’s proposal will offer loads of opportunities for statewide coalition-building on all sides of the issue, especially in a high-turnout presidential election year.

Support already looks solid across the business community, which has provided broad backing for Better Together’s efforts. The age of the electorate could also be a crucial factor. Insiders at Better Together say the organization’s early polling indicates voters under 45, who are less tied to the structures of the past, would favor a merger.

Would polling like this be enough to entice young politicians – especially young African-American politicians – to come out in support of the Metro City plan? Will Ross, an associate dean at Washington University and a member of the task force, seemed to be imploring them to step forward at Monday’s event when he argued that rather than diluting the influence of black leaders, Metro City’s structure would give African-Americans greater ability to address regional issues such as health disparities, policing standards and neighborhood revitalization.

As for outstate voters, trying to gauge their intentions is tricky, especially before Better Together’s campaign kicks off in earnest. Plenty of rural voters may dislike St. Louis, but how would that manifest itself on Election Day? They could vote for Metro City because they believe the current St. Louis City government is beyond redemption and should be abolished, or they could vote for Metro City because they think it will result in a safer, cleaner, livelier place to visit for ballgames or the theater. Either way, Better Together scores votes.

Some voters may even endorse Metro City because they believe urban, suburban and rural residents of the state have quite a lot in common, with a shared future as Missourians. If that happens, and its initiative passes, Better Together would be able to claim more than just an election victory. It would be able to assert, beyond any doubt, that in the end it lived up to its own name.

Editor’s Note: This article is co-published with mcphersonpublishing.com.