When The Pruitt-Igoe Myth appeared on DVD a few years ago, the filmmakers provided a little-known short from 1970 called More Than One Thing. In this film, directed by Steve Carver, a teenaged Pruitt-Igoe resident named Billy shares his life, loves and philosophy. While scenes of Billy’s world at the housing project are eye-opening, what is most striking is how downtown serves as an extension of his world.

When bored, Billy and his crew head south and walk down Olive Street. They end up at Famous-Barr, inside of the now-empty Railway Exchange Building at Seventh and Olive Streets. They prance and dance, taking the business district’s staid setting as a backdrop for the exuberant curiosity of youth. The open street grid between Pruitt-Igoe and downtown makes the city an equilateral space for exploration and encounter – just pick a direction.

Today, the world of Billy and his friends barely exists. Pruitt-Igoe is gone, of course, but so are most of the other places Billy visited in the film. Franklin Avenue, now called Dr. Martin Luther King Drive, does not sport countless neon-lit blade signs reflecting slow light onto plate glass shop windows. Olive Street west of Tucker Boulevard is a somber, pompous thoroughfare, devoid of a pedestrian pulse save for the strip around Hard Times Lounge and the White Knight Sandwich Shop. The center of downtown vacillates between moments of inviting urbanism and absurdly-located loading docks, parking lots, inexplicably vacant shop fronts and expansive blank walls. Thank goodness for Bird and Lime scooters, or today’s teenagers would be numbed by most of our center city.

A previous generation intervened into this landscape when the city’s convention center, once called Cervantes Convention Center but now called America’s Center, pursued major expansion in the early 1990s. Mayor Vincent Schoemehl, Jr., Comptroller Virvus Jones and others presided over a process that corrected the design flaws of the original convention center building completed in 1977. That building was a hulking, neutral, disconnected modernist form, barely notable as architecture for the placement of a now-removed Ernest Trova sculpture, AV/Bedu.

Placed along Delmar Boulevard, which was christened “Convention Plaza” east and west of the modest superblock, the old convention center represented all that was wrong with modernist urbanism – a segregated monocultural island, distant from the real vital center of downtown and removed from every spark around it.

Under the expansion designed by HOK, which included input from principal Gyo Obata, the convention center drew south toward Washington Avenue, and then connected to the football stadium also designed by HOK to the east. The decision to place the football stadium adjacent to the convention center had some tactical viability – the able opening of walls and connection of the convention rooms into a stadium hosting only eight home games per year – but it was a clod of an urban design choice. The convention center’s four-block mass became a cancerous form, and annihilated many fine urban buildings in the process. Even the modernist gem of the Greyhound Bus Terminal (1964; Schwarz & Van Hoefen), was subtracted. The convention hotel, a tall and expensive building, felled to make the stadium. The new form was a hostile, hungry alien.

HOK made the best of the circumstance, though, by drawing the convention center onto Washington Avenue with some grace. The architects dropped the tedious modernism of the old building in favor of a postmodern idiom that addressed the classicism of the Washington Avenue warehouse district to some degree. The new primary elevation repeated a cliché in its red brick, but attempted some relational grasp with cast stone panels mimicking ornamental terra cotta, and a cavetto cornice that echoed the top parts of adjacent buildings. Where 8thStreet dead-ended at the new form, the architects placed a rotunda capped with a Byzantine dome, which mitigated the long view fallout. If the street view should terminate on a wall, make that wall worth noticing.

The gestures of the new form could not avoid pitfalls such as the simultaneous choice to build an off-site parking garage and hotel ballroom to the west that remains one of downtown’s most woefully tepid buildings. The convention center and stadium presented a butt end to the north, devoid of anything but loading docks and canopies. While the center approached downtown with deferential reverence, it showed Columbus Square its back side. The form also devoured Seventh Street, isolating the area that later would fail to jump-start as the “Bottle District.” The teenagers of the 1990s would have to take the long way around.

Now we have our own chance to make this urban form more responsive to the city, but that’s not what the video released by the Convention and Visitors Commission showing the proposed expansion depicts. The video shows that we may do worse over twenty years later. The form extends the north side of the center so that there is a giant “T” shape. This form addresses current operational problems, such as the ballroom and kitchen being on separate levels. There also will be an additional 90,000 square feet in convention space, which supposedly will boost the center’s revenue generation by 36% according to Johnson Consulting.

One might argue that the loss of the Rams and the now 365-day availability of the stadium for convention use should have done something. One might also raise the issue that convention center economic studies are the weakest prophecy this side of Miss Cleo, at least according to scholar Heywood Sanders in Convention Center Follies. Yet for urban design critique, let’s take these needs at face value.

It is harder, though, to take the supposed need for a new plaza on a block between 9thand 10thstreets north of Lucas Avenue, touted to serve the center and downtown workers. This park is only one and one-half block down and one block over from Old Post Office Plaza, which certainly is not buzzing year-round. One block east of that plaza is the US Bank Plaza, built by predecessor Mercantile Bank in 1997. Both portended to alleviate the supposed lack of open park space for daytime occupants of downtown. Both struggle to convince anyone that there is much of a daytime – let alone night time – population downtown. The convention center should figure out how to bridge to these spaces and send people walking across Washington Avenue. A convention center is an island only if its parts are all on one contiguous block.

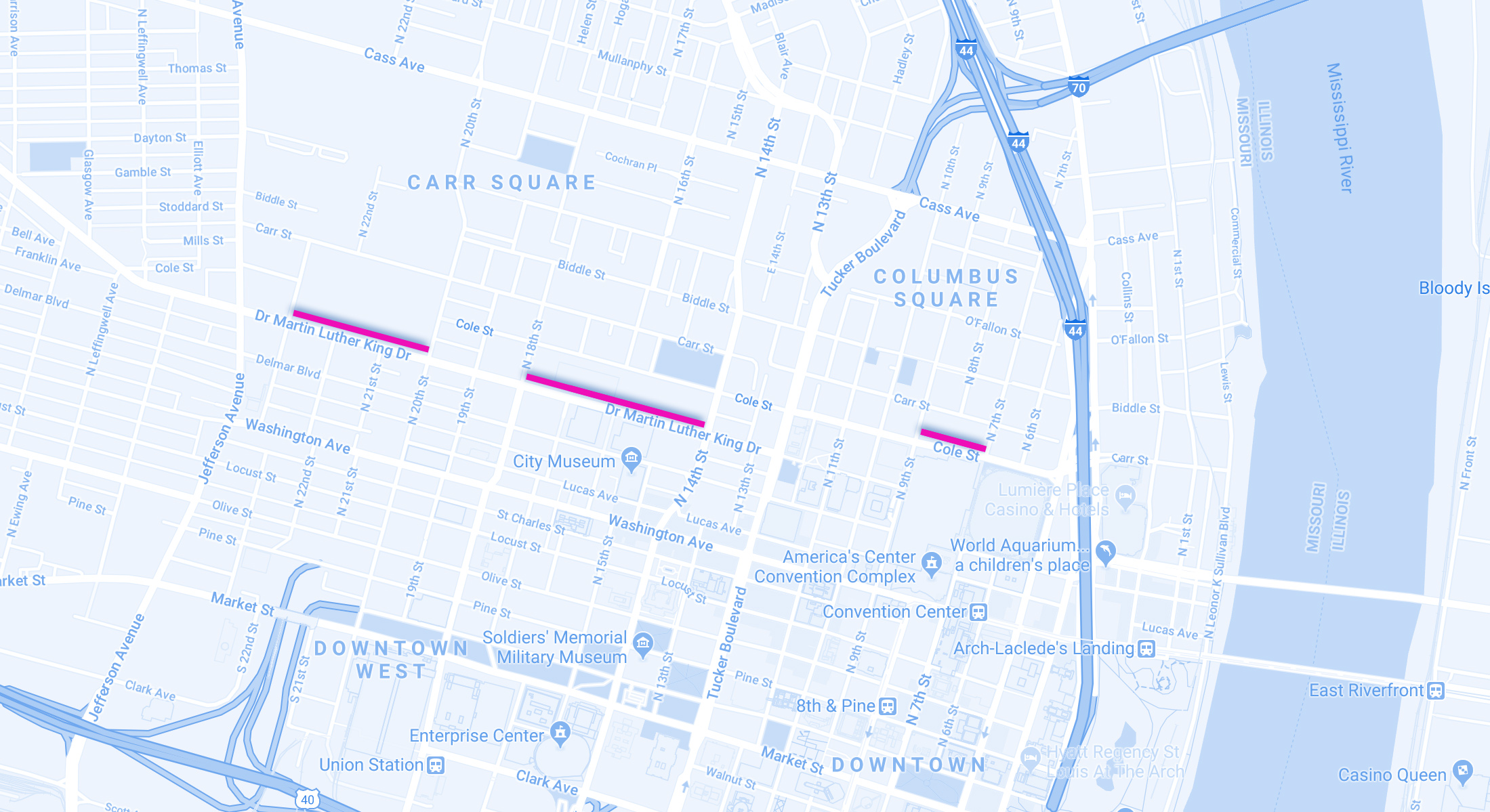

The worst impact of the convention center expansion, though, will be the closure of Ninth Street, which will bring into force the closure of 12 of the 21 street crossings north or south of Delmar Boulevard on the edge of downtown. Facing Cole Street – facing the residents of Columbus Square – will be an additional 26 loading docks, with a total of 38. Our city, which has assiduously probed the residual permeation of the Delmar Divide, still appears to have a partial consciousness. The convention center/stadium mass will close along Cole Street from Broadway to 10thStreet. Just west, one block north of Delmar, Dr. Martin Luther King Drive is closed between 14thand 18th streets. Then further west, Dr. Martin Luther King Drive is closed at the north between 20th to 23rd streets.

Convention centers across the United States are not much different generally, but some projects point the way to mitigating the heavy forms. Take Tod Williams & Billie Tsien’s concept for the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago’s Jackson Park. The architects have separated the form into three major components, connected below grade. Like America’s Center, the Obama Presidential Center is service-heavy in its spatial uses. Yet the architects have avoided a monolith, and allow the spaces between built forms to be meaningful, dynamic spaces.

Although the Obama center is a much more significant project with a larger architectural budget, its principles are not a luxury. America’s Center could be expanded with a distributed form, allowing for north-south circulation. The sidewalk interfaces could be inspiring rather than glum. A new section could draw upon the 1990s expansion, with its embrace of the street, instead of the moribund original section with its sorrowful Berlin Wall-like expanses.

Building more of a wall between downtown and north city serves as more evidence that urban design is an afterthought in St. Louis city government. The north side and downtown are naturally connected on the same expanse of bedrock supported soil. South of downtown, there is a natural gap where the rail yards occupy the Mill Creek depression. The Chouteau Greenway could eventually spend hundreds of millions of dollars to join the city back together at this break. Today the city aims to spend $175 million to make more of a gap at the north side of downtown. The impact is troubling, while the optics are puzzling.