Old St. Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church rises out of the weed-choked lots of the St. Louis Place neighborhood, just west of Parnell Street. There are not a lot of towering landmarks up this way, particularly with the demolition of the nearby Bethlehem Lutheran in 2014 – so the stark, Gothic spire of the church, towering 150 feet above the empty streets, presents all the more abrupt interruption in the landscape.

It sits along the almost anonymous one-block stretch of Lismore Street where it intersects with Hebert Street. Hebert possesses a handful of houses that are still occupied, their owners proudly and resolutely holding out. To the south of the church, on Sullivan, is a different story. The houses are all vacant, mostly hit by brick thieves, and there’s this weird compound in the ruins of an old furniture factory, full of junk, where men burn rubbish and other debris and stare warily at passersby who intrude into their domain.

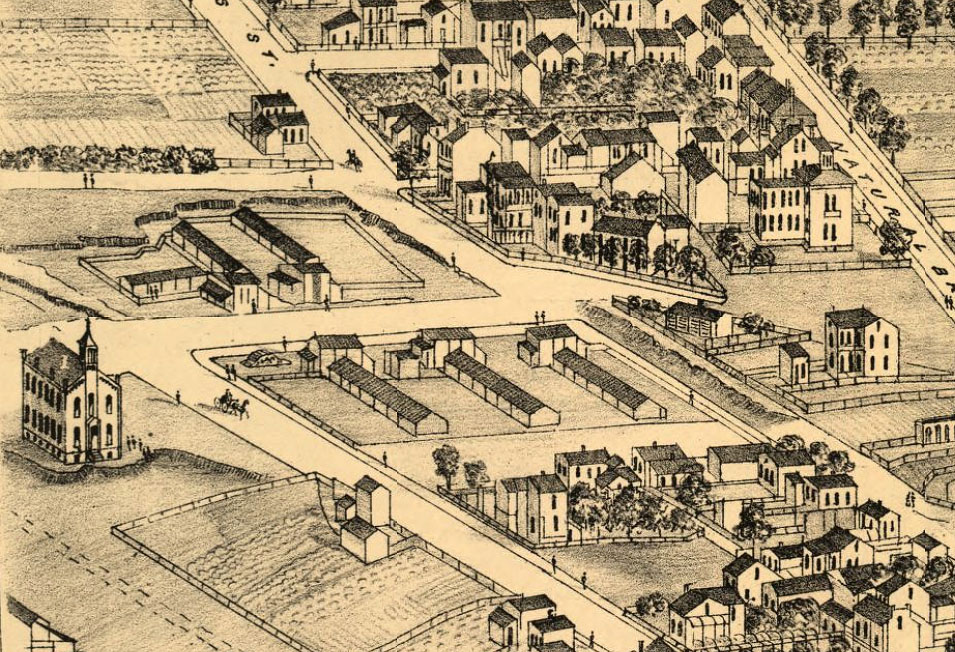

Ironically, in many ways, the current windswept grasslands of vacant lots, many owned by Paul McKee, look much the same as it would have back in 1874, when this was the edge of the city, and a small but rapidly growing parish was founded, giving yet another German speaking Roman Catholic parish a place to worship. There were almost two dozen German national churches at one point in the Archdiocese of St. Louis, with the parishes distributed evenly between north and south. The original small church appears in Pictorial St. Louis, published by Compton and Dry in 1876, with the Grand Prairie still stretching out to the west beyond.

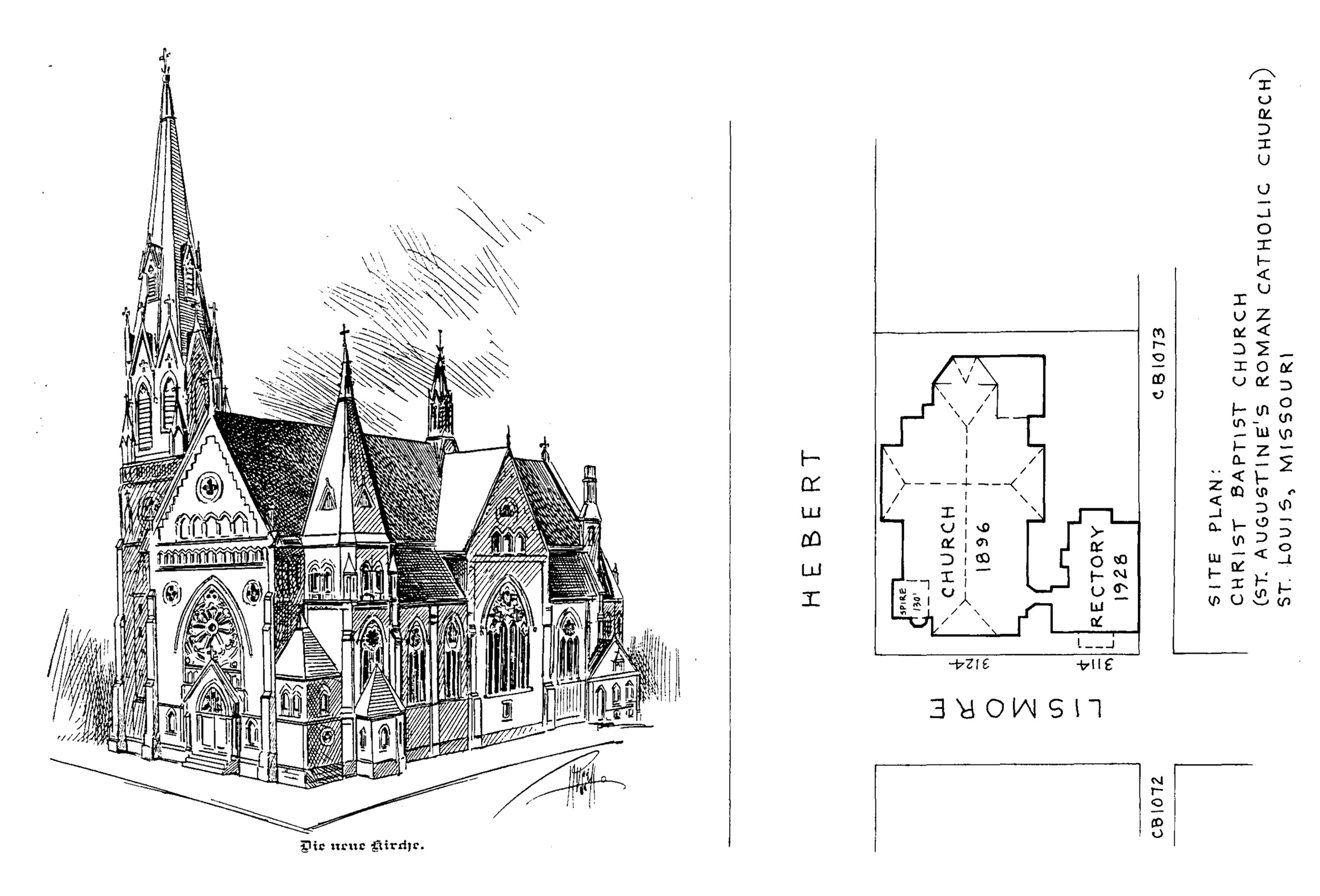

That little church quickly became too small, and one of the great architecture firms of St. Louis, Louis Wessbecher, often paired with Edward Hillebrand, with offices in the Temple Building, was enlisted to design a massive new St. Augustine’s to accommodate the growing parish. Wessbecher was born in what is now the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg. When he came to America in 1882, he developed a multifaceted practice, designing ecclesiastical buildings for both the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches. Besides designing the nearby German Gothic Revival Bethlehem Lutheran Church, Wessbecher is also responsible for the still open St. Stanislaus Kostka Polish church. For each commission, he looked to the characteristics of the congregation’s home national identity to give a distinctive style to each church.

Logically, then, for St. Augustine’s, Wessbecher chose the German Hallkirche, or hall church, variant of the Gothic style. German nationalism of the Nineteenth Century was a strange creature; it was a child of Romanticism, the movement that sought to break away from Neoclassicism and its often-cold reliance on ancient Greek and Roman art and culture. For the German Romantics, the purity of Teutonic culture was best manifested in the Gothic style, even though ironically it had originated in France, its traditional enemy since the Ninth Century. Perhaps then, the German Gothic Hallkirche, which rejected the use of the distinctively French Gothic flying buttress, was a good compromise.

German Gothic hall churches possess no clerestory windows to light their naves, since the aisles rise to the same height as the central worship space. Consequently, all light enters through tall pointed Gothic windows lining the aisles; the apse, where the high altars sits; the transepts, which cut across just in front of the apse; and the windows of the front façade. Ribbing, stone arches that provide the skeleton upon which brick or stone groin vaulting then rests, remain a hallmark of the Gothic in all countries

Looking at St. Augustine, the church fits all the criteria of the standard German Gothic Revival Hallkirche, complete with the asymmetrical placement of one bell tower which is much taller than the other on the front façade of the edifice. It was never planned this way in Germany, but as was often the case, funds being tight, usually one bell tower was completed, and the money ran out before the second was completed. The Romantics fell in love with this picturesque asymmetry, and throughout America lopsided church façades featuring mismatched church towers are prevalent, St. Augustine included.

At one point, St. Augustine had thousands of members in its parish, and newspaper records reveal that the church functioned in every aspect of life for the community. There was a school across the street, and there were numerous clubs and sodalities, or societies, that adults joined for social and professional reasons. From birth until death, when obituaries chronicled the funeral rites from the church to Calvary Cemetery, the church building was just part of the scenery of North St. Louis.

All that is gone now. A series of small congregations tried to hold the mantle of responsibility for this massive brick, stone, copper, wood, terracotta and stained-glass monument to St. Louis architecture and craftsmanship. While the method of constructing the ribbed groin vaulting of St. Augustine’s is similar to its Medieval counterparts, St. Louis’s builders substituted in wood lathe for stone, giving the appearance of the hulls of great wooden ships when viewing the vaults from above. All those vaults have now collapsed, the victims of water infiltration. The beautiful slate roofs don’t keep out the water anymore because someone has stolen all of the copper flashing that keeps the water out of the eaves.

On the outside, the stripping of copper has brought down large chunks of masonry, which has further allowed water to pour into the church when it rains. The beautiful original wood benches and altar rail are still in the church somewhere, but they’re buried under huge piles of wet, moldy plaster and wood that have fallen from the ceiling. The terracotta is starting to fall from the front of the church as well, destroying what had once been a monogram of St. Augustine’s name.

I’ve long considered the fate of St. Augustine’s to be a metaphor for North City. Still beautiful, increasingly stripped of its wealth by those only interested in enriching themselves, and increasingly running out of time. Where do we go from here?