The Office of the Missouri State Auditor, Nicole Galloway, recently released an audit on Community Improvement Districts (CIDs) in the State of Missouri. The findings uncovered significant weaknesses, including opportunities for conflicts of interest, mismanagement, and abuse of taxpayers funds.

Community Improvement Districts are a type of special local taxing district administered on the local level; they collect revenue within their designated boundaries to pay for public facilities, improvements and services. From the Missouri Department of Economic Development (DED), “CIDs are created by ordinance of the local governing body of a municipality upon presentation of a petition signed by owners of real property within the proposed district’s boundaries, typically encompassing a commercial, not a residential area. A CID, although approved by the local municipality, is a separate political subdivision with the power to govern itself and impose and collect special assessments, additional property and sales taxes. CIDs may also generate funds by fees, rents or charges for district property or services and through grants, gifts or donations. CID annual reports are filed with the Clerk of the creating municipality and a copy filed with the Department of Economic Development which does not have oversight or audit responsibility for these districts.

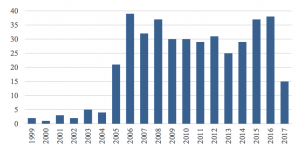

The number of CIDs formed in the State of Missouri by year has increased dramatically in the past decade, with over 25 new CIDs formed each year every year since 2006, with the exception of 2017. As of December 31, 2017, there were 428 CIDs in the State; in the year 2017 alone, CIDs received more than $74.3 million in sales tax and other revenue. “Due to the increasing number of CIDs in the state, and the significant amount of public money collected and spent by such districts, state laws establishing CIDs are a significant issue to taxpayers.”

The report concluded that “significant changes to the State’s Community Improvement District (CID) laws are necessary to protect taxpayers…State law requires municipalities to approve the petition to form a CID. However, state law does not require CID petition documents to include a well-defined purpose, does not require the lifespan of a district to be limited or specifically defined, and does not require any estimate of how much revenue will be collected or an evaluation of the merits of the district. As a result, districts are collecting an unspecified amount of taxes or assessments for undefined purposes for an unknown period of time.”

Words like “unspecified,” “undefined,” and “unknown” are not ones that any taxpayer wants to hear regarding their tax dollars. Around 73% of the revenue collected by CIDs comes from sales tax. While taxpayers generally vote on sales tax amendments, CIDs are allowed to impose taxes with minimal input or oversight.

The audit found that roughly 83% of CID Boards are controlled by developers and property owners; while not surprising, as they have a vested interest in improving the community, State law does not require Boards to competitively procure construction contracts, nor does it require anyone independent of the

The Downtown St. Louis CID was one of the 15 CIDs selected for further evaluation as part of the audit. The audit found that this CID did not competitively procure management services, and roughly $1.6 million was spent on those “management services” between July 2016 and June 2017. The petition filed to create the Downtown St. Louis CID required the District to contract with a not-for-profit operation organization for management and operations; however, the D

The audit also uncovered issues with annual budget reporting, inconsistencies with charging the CID-prescribed taxes (both inside and outside of the designated CID boundaries) resulting in improper taxation, and an overall lack of enforcement.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the current number of active CIDs within the City of St. Louis is somewhat unclear. The audit indicated that there were 60 active CIDs in St. Louis City at the end of 2017. Some of these districts encompass several city blocks (like Downtown St. Louis), while others contain only a single property.

If ample opportunities exist for conflicts of interest and corruption in the City’s largest CIDs, those that contain only one parcel bring up additional concerns. The Department of Revenue (DOR) asserts that money collected for CIDs with fewer than 6 businesses must be protected from disclosure to the general public. As an example, the 2350 S Grand Community Improvement District is a single Starbucks location. Their 2017 revenue was “redacted” from the report due to the DOR’s provision; their “Estimated Project Costs” for 2017 were disclosed, and total $130,000. It is unclear what public facilities, improvements, or services a single Starbucks location provides to their “community” using taxpayer dollars.

The Tucker and Cass CID, located in North St. Louis, appears to be Paul McKee’s personal Community Improvement District. The six parcels located within the district boundaries are all owned by LLCs of McKee’s, and the petition for the CID indicates McKee is one of the Board members. As with all CIDs of 6 properties or fewer, revenues collected by the CID are

The collected revenue for over a third of the CIDs in the City of St. Louis is similarly shrouded in mystery. The audit also found that (1) in 25% of the districts reviewed, there were businesses inside the districts that were not remitting CID sales taxes to the DOR; (2) in 75% of the districts reviewed, there were businesses not charging the CID sales tax at all, and (3), in 17% of the districts reviewed, there were businesses outside of the district boundaries that were charging the CID sales tax anyway. Such errors arise when the CIDs fail to report new businesses to the DOR.

The 60 CIDs in the City of St. Louis cumulatively collected nearly $6 million in sales tax

The audit concludes with several recommendations in the public’s best interest. At the present, no state or local entities have oversight or management responsibilities over CIDs. Enacting change may be difficult, but necessary; in the meantime, business owners within CIDs should seek transparency and accountability as it relates to each CID’s budget, planned improvements, bid process, and more.

The full audit is available here.