It has only been two hours since I saw the photo above (taken July 3, 2018) that includes Mayor Lyda Krewson (amongst other older, white representatives of the project) at the ribbon cutting for the Gateway Arch ground’s re-opening in St. Louis, MO.

In her post sharing the photo, Mayor Krewson expressed, “The revamped Gateway Arch National Park & museum are perfect examples of what we can accomplish when we work together — local, state & federal partners, private donors, & YOU the voters. City & County voters came together to create this amazing attraction for our region.”

However, the moment captured does not reflect “perfect examples” of the constituents listed. This photo exists alternatively as an embarrassingly effective example of the region’s inability to evoke the essence of non-white leaders affecting change in the physical and social redevelopment of our city. Both literally and figuratively, the people featured in this photo do not have the people behind them. More shamefully, they do not have the people amongst them. And, the people of St. Louis deserve better. Our progress as a region demands better.

The erasure of people of color — black people specifically as the largest racial demographic in the city — mirrors images that one would expect from the current administration that is running ruining our country. Moreso, it reflects the very reason that CORE activists, Percy Green and Richard Daly, scaled the St. Louis Arch in 1964 to protest the exclusion of black workers being included in its initial construction.

Last week, I shared thoughts about St. Louis regional development with the non-profit media outlet, Next City, because of my involvement as a black designer, activist, and engagement strategist with the Chouteau Greenway, another local public project that will stretch from Forest Park to the Arch and riverfront.

In the article, I expressed my initial hesitation with engaging such public works because so often “people of color have been left out of the process, left out of having access to these spaces.” And I must reiterate, “it is a harmful cycle that continues to traumatize people who look like me” when we see spaces lauded as an inclusive, but are visually gaslit with images, messages, symbols, social policies, and behaviors that communicate otherwise. The ribbon-cutting image of the Arch is indicative of these sentiments. It does not express that the Arch is a welcoming or inclusive space for all demographics of people in our city. And as a region, we must progress to a place within our collective consciousness that we can see these visual cues and envision better.

…

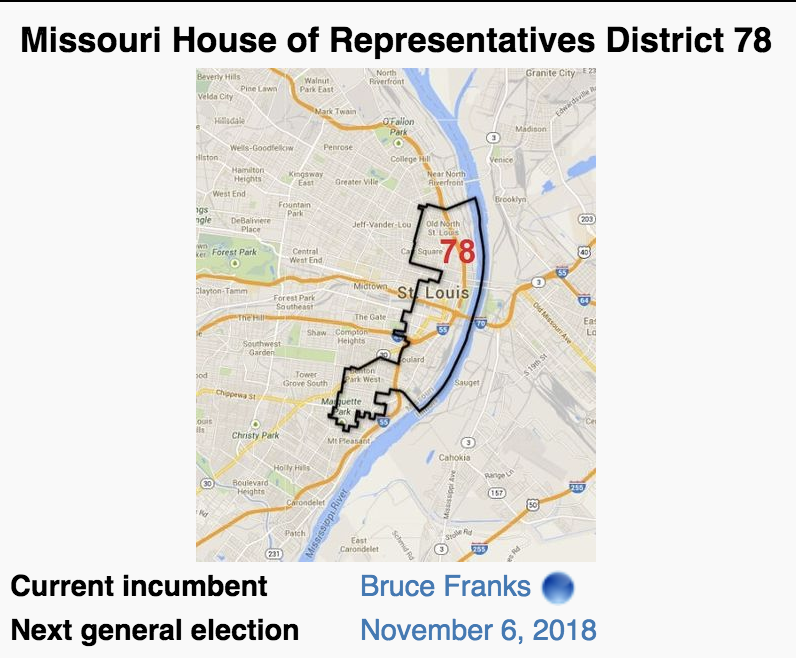

Since seeing the photo on the morning of July 4, 2018, I have learned that at least two prominent local black leaders are connected to the Arch’s redevelopment. Fellow activist and artist, Bruce “OOOPS” Franks, serves as the Missouri State Representative of the 78th District of our state, which includes downtown St. Louis and the riverfront. Though his role falls within the “local, state, & federal partners” category of people that Mayor Krewson lists, he is not included in this moment.

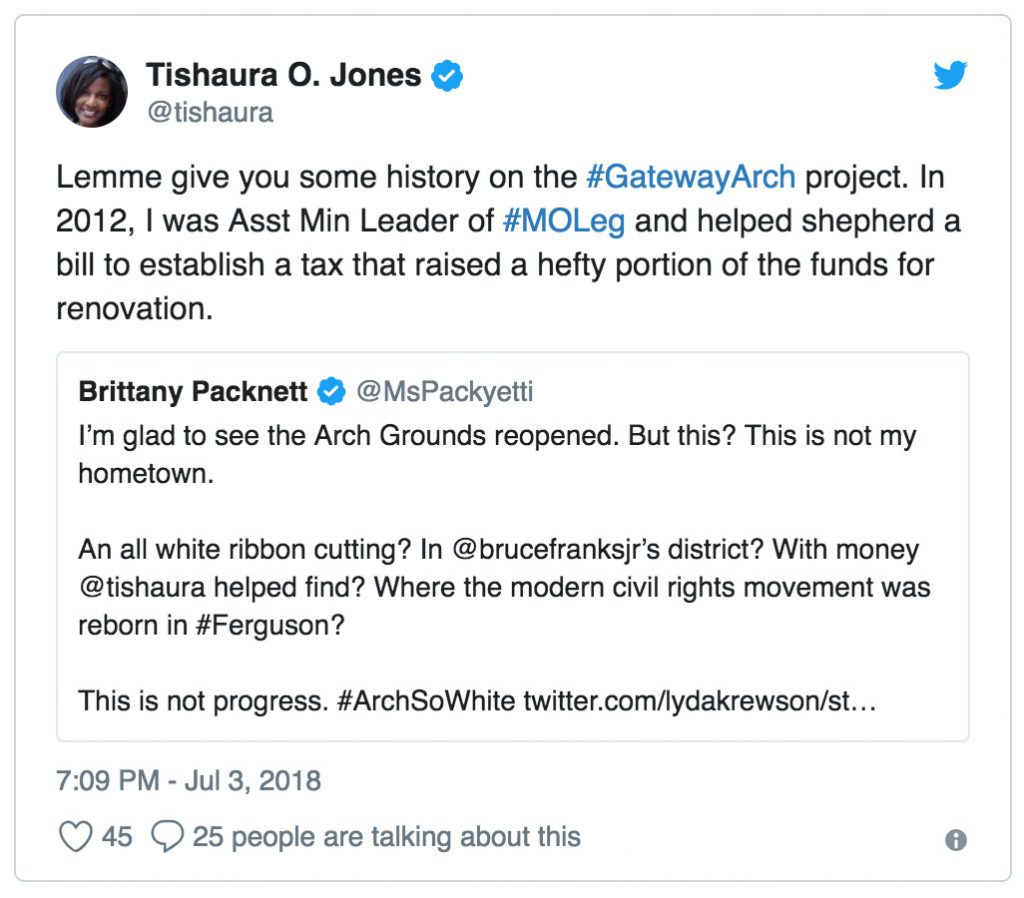

Tishaura Jones — our city’s treasurer and 2017 mayoral candidate — expressed via Twitter that “In 2012, I was Asst Min Leader of #MOLeg and helped shepherd a bill to establish a tax that raised a hefty portion of the funds for renovation.”

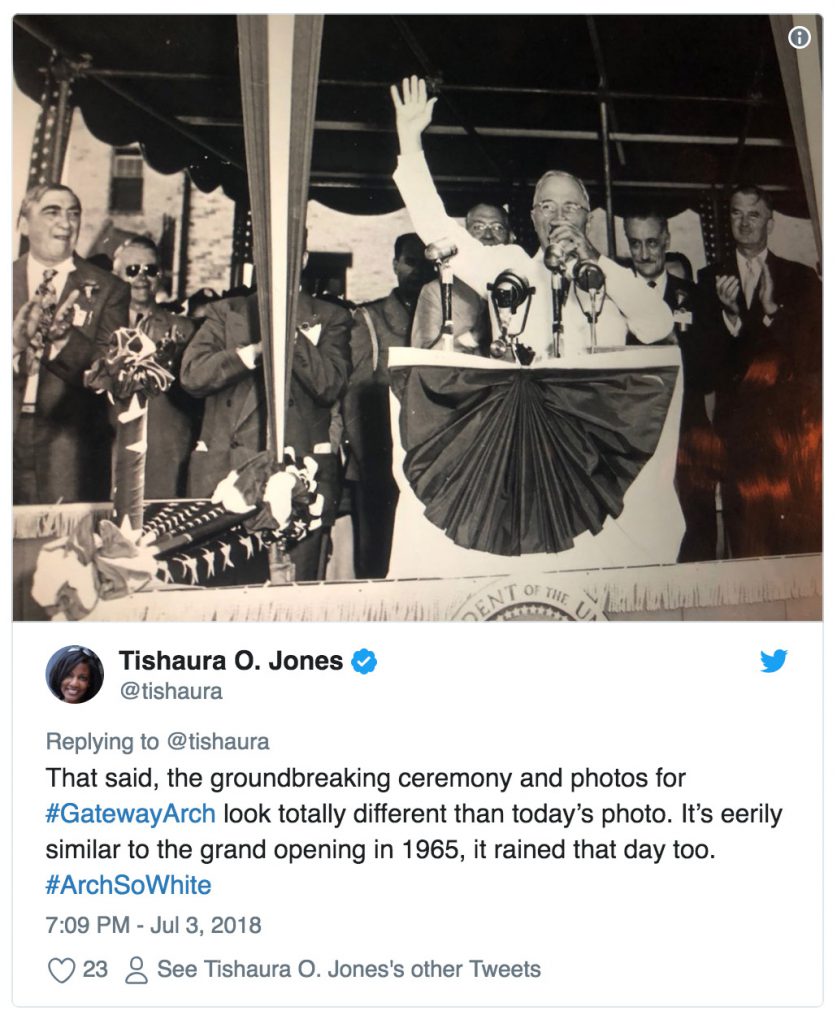

She then shared a thread of additional history of her (and others’) involvement, including an “eerily similar” photo from the 1965 Arch ground opening to illustrate how regional developments have been consistently monopolized by the narratives and images of white leaders at their helm.

The difference in the 1965 photo and the 2018 ribbon cutting is that we should know better by now. Our struggles and trials as a region — especially since our regional uprising in 2014 — should have alarmed participants in this ceremony to consider the narratives that a racially homogenous photograph would send. It should have alarmed someone — perhaps at least Mayor Krewson, who includes within her mayoral administration the role for a “Deputy Mayor of Racial Equity and Priority Initiatives” — to stop the photo opp and welcome others into this celebratory opportunity. Even if it were not political leaders like Jones or Franks, they could have welcomed team members, administrative staff, site designers, construction workers—others involved in the process — to take part. Moreso, if “the revamped Gateway Arch National Park & museum are perfect examples of what we can accomplish when we work together,” as Mayor Krewson expresses, then this moment could have included community members, residents, voters, children, people who differently-abled, queer people, people of different faiths, and anyone else who might seek the Arch grounds as a place for them. This moment could have embodied the togetherness of which Mayor Krewson remarks, but instead, it is a stark reminder of what we still must face in our pursuit towards regional racial and cultural equity.

Some may question why a photograph might upset local St. Louis citizens so deeply. Others may feel that people are responding too sensitively to what is but one moment throughout the Arch’s years-long redevelopment process. We must be reminded, though, of the impact that symbols like the arch and images like the ribbon-cutting photo carry. Representation is often the first step on the path towards equity, and for a region that is desperate to fulfill the racial equity goals that thousands of people have worked toward since the Ferguson Commission of 2014, representation in these moments matters tremendously in our city. And let’s be clear, this issue is not about political and civic leaders of color being included in a photograph. It is not simply about showing that there is non-white leadership involved in projects and developments like these. It is about reflecting the promise of a city. It is about unearthing the possibility that the contributions of non-white/cis/wealthy people will be recognized, honored, and celebrated too. It is about building a reality that proves access to such spaces is afforded to all who live, visit, and engage with the space. It is about affirming that the Arch — the icon of our city — is a place for all of us.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally appeared on Medium. It is republished here with permission from the author.