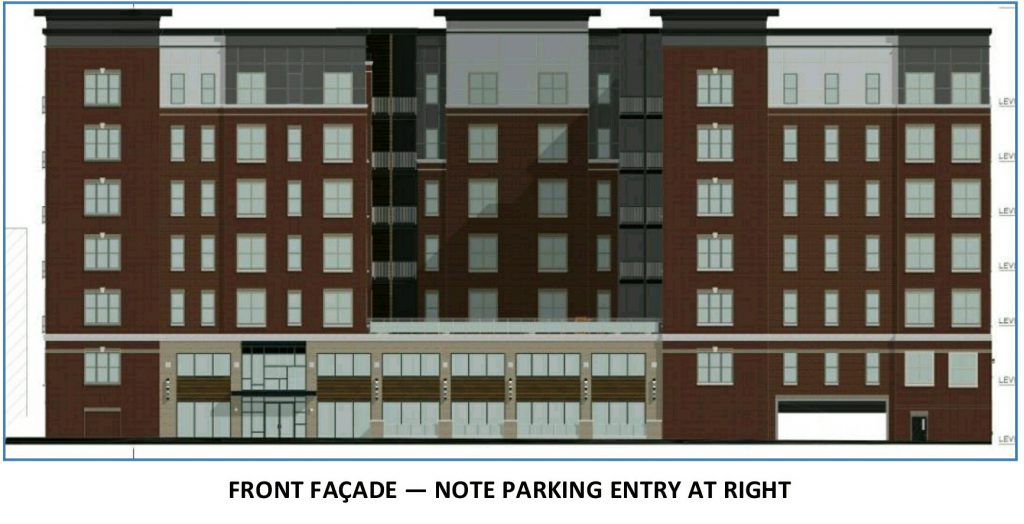

Next week, Rainier One LLC will present a revised proposal for new construction at 5539 Pershing in the Central Corridor’s dense and vibrant DeBaliviere Place neighborhood. Plans call for a seven-story building, with a U-shaped five-story block of apartments wrapped around a third-floor courtyard, all resting atop a two-story parking garage. The lobby and building amenities face Pershing through street-level storefront openings. The storefront elements and decorative detailing have been added since a previous proposal. VE Design Group is the architect. The location once had been the site of a community pool and tennis courts but in recent years has been a surface parking lot.

The city’s Cultural Resources Office is recommending the Preservation Board approve the revised proposal on condition that no additional curb cuts be added along Pershing. The developer has proposed a garage entrance directly from Pershing. If the Preservation Board follows the CRO recommendation, the garage opening facing Pershing will disappear, and the developer will have to redesign the garage to allow access only from the existing driveway to the east.

Twice as tall as its neighbors, the proposed structure does not comply with the historic district standards on height. Nevertheless, the city is recommending approval on account of the recessed courtyard design and the presence of other tall residential buildings along Pershing including the 17-story Congress Apartments, the 8-story Branscome Apartments and the 8-story condo building on Belt Avenue around the corner from the proposed project. The same developer is constructing a six-story apartment building with structured parking across the street from the proposed project at 5510 Pershing.

Located between DeBaliviere Avenue and Union Boulevard north of Forest Park, DeBaliviere Place is the westernmost part of the Central West End Historic District. Established in 1974, the district was created to maintain the distinctive character, construction quality, and architectural integrity of the neighborhood, including the neighborhood’s pedestrian scale and sense of place. The standards for the district do not prohibit modern design.

Debaliviere Place is one of those places that make St. Louisans feel like they live in a big city. The south side of Pershing includes some of the most densely populated blocks in the St. Louis region with apartment buildings ranging from five to 17 stories tall. Forest Park Parkway snakes through the southern edge of Debaliviere Place. New construction fills in gaps between historic properties. Two Metrolink lines merge here, and typically one can hear the staccato thump-thump-thump clicking of a roller bag on the concrete sidewalk as neighborhood residents make their way to or from the airport via the Forest Park Metrolink station. A streetcar — er trolley — opens this year along the neighborhood’s western edge.

Apartments and condos dominate the neighborhood, with single-family homes limited to the mansions along Washington Terrace, Kingsbury Place and Waterman Place — plus one lonely shingle style Victorian nestled among all the condos at 5515 Waterman. It pre-dates the neighborhood. Local residents gather at a community pool on Waterman or at Pig & Pickle, newly opened in the space vacated by Atlas. Residents walk to the zoo, the history museum and the MUNY.

Built mostly between 1910 and 1925, Debaliviere Place was one of the most fashionable addresses in the city. The neighborhood was home to professionals who could rent or own the large apartments with multiple bedrooms, formal dining rooms, and luxury finishes. Residents supported commercial strips along DeBaliviere and at nodes along Pershing. A streetcar ran down Pershing, connecting commuters to jobs downtown. But the 1950s and 1960s were decades of decline. Aided by the FHA and the highway department, the urban exodus began after the Second World War, aided and abetted by fear of a racially mixed St. Louis. Many of the grand apartment houses of DeBaliviere Place stood vacant. Some were demolished. A 1985 article in Fortune magazine speaks of “the dangerous, semideserted mess” the neighborhood by the late 1970s had become. “You needed an armed guard to go there.”

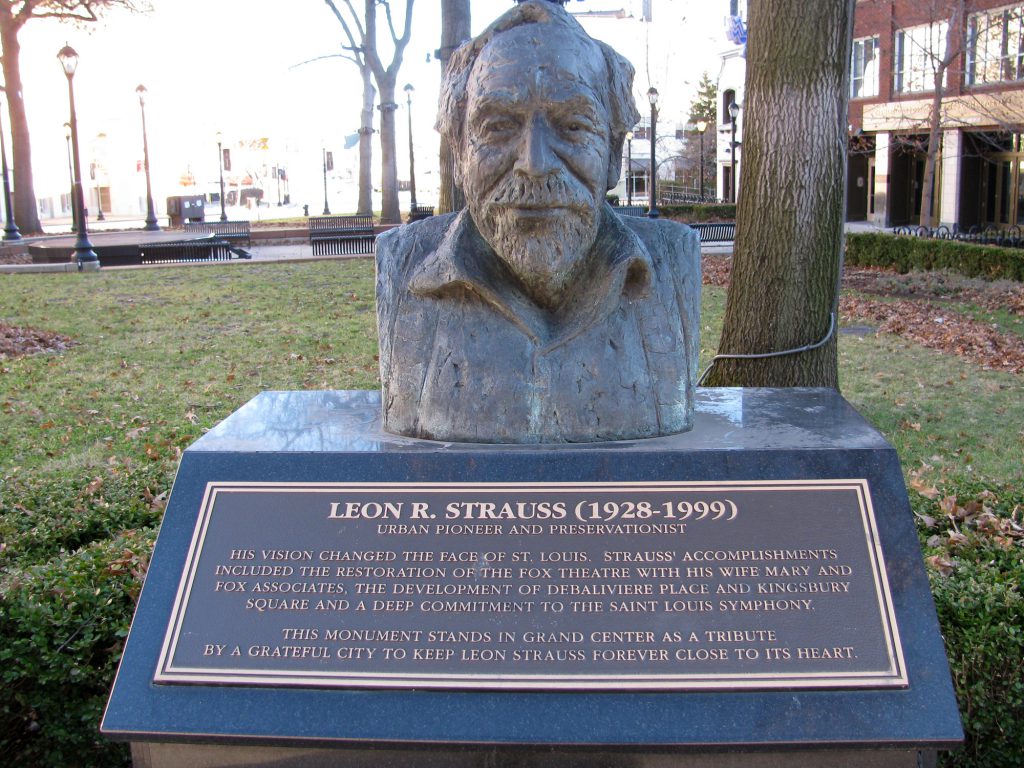

The neighborhood’s resurgence was the brainchild of Leon Strauss and his Pantheon Corporation between 1979 and 1988. Half a century before Paul McKee’s still elusive Northside, Pantheon Corporation quickly took control of 106 acres of urban blight, including 1,651 apartments and commercial buildings. The city declared the neighborhood a Missouri Statute 353 Redevelopment Area. Strauss — also known for reopening the Fabulous Fox — moved existing tenants into units they could afford and got a line of credit from Mercantile Bankcorp after every other bank turned him down. The city provided tax abatement, and Pantheon took advantage of federal historic tax credits totaling 25% of qualified expenses. Historic buildings were restored. Severely damaged buildings were gutted and rebuilt on the inside. New construction filled in gaps in the urban landscape. As part of the agreement with the city, Strauss set aside 300 units as Section 8 affordable housing. Many other buildings became market-rate condominiums, providing a core of long-term homeowners within the neighborhood, particularly along Waterman. Fortune magazine in 1985 called DeBaliviere Place “the most ambitious neighborhood resuscitation ever undertaken in America.”

Clever promotional materials poked fun at the generation that had fled. Tee shirts read, “DeBaliviere Place. Don’t tell your parents where you live.” By the late-1980s, the neighborhood felt like a European village with fountains and plazas, lush landscaping and corner retail — yet still with the energy and beat of a dense American city. Small investments came on top of the big ones. New businesses opened — restaurants on Pershing, a video rental at Union and Pershing and a coffee shop on Belt. Sculptor Bob Cassilly even designed new terraces for the Blenheim Court condos at 5535-39 Waterman. Those terraces look like City Museum for a reason, but the terrace redesign came first. Many of those Pantheon apartments later underwent conversion to condominiums in the 2000s.

It’s a diverse place. For decades, a sizable community of Russian Jews inhabited the neighborhood. Even as the neighborhood gentrified, it retained a global feel with international students, medical residents and people moving in from everywhere. At the 2010 census, the neighborhood had 3,466 residents, up 1% from a decade earlier. In 2010, DeBaliviere Place was 59% White, 29% Black, 8% Asian, 3% Hispanic and 3% mixed race. School buses drop children off at their homes on Pershing after school on weekdays. In the summer, kids play in the fountain at Clara. The neighborhood includes some of the poshest private streets in St. Louis but still remains home to some of the city’s poorest residents. The St. Louis Housing Authority has 120 public housing units in an 11 story tower at 5655 Kingsbury, and The Branscome on Pershing has 108 units of Section 8 housing marketed to seniors. Every winter, twenty homeless women sleep in the basement winter women’s shelter at Grace and Peace Fellowship at Clara and Delmar, where hundreds have relied on the food pantry for assistance. They belong here, too. We’re all residents.

The revised proposal for 5539 Pershing is a vast improvement over the developer’s previous iteration. It weaves a surface parking lot back into the fabric of the city. If the developer agrees to move the garage entry and curb cut facing Pershing, then the design could add welcome density to help support the retail node at Pershing and Belt. We are rebuilding St. Louis. That’s the vision, and this project fits.