Earlier this year the Cardinals debuted their in-house TV show, Cardinals Insider, which aired all season long on Fox Sports Midwest and every Sunday on Channel 5 in St. Louis. It’s billed as “a weekly news magazine television show…that provides fans with unfiltered, behind-the-scenes, insider access to the Cardinals from team journalists,” and is “[j]am-packed with exclusive interviews, news features, profiles, unrivaled player stories and more.”

Cardinals Insider is not really any of those things. It’s an infomercial; the average episode mixes a few short, mildly engaging segments like “Ask A Cardinal” with straightforward promotional spots for various ticket packages, merchandise, giveaways, stadium amenities, and the like. It’s a slickly produced brand-management exercise whose express purpose is to cast the organization in the best possible light. Some of the last words that anyone could reasonably use to describe it are behind-the-scenes or insider.

And that’s fine—the Cardinals are certainly well within their rights to market their business (and itis a business) however they see fit. But there’s a line between boosterism and propaganda, and last month, in a Cardinals Insider segment marking the tenth anniversary of Busch Stadium III, the Cardinals crossed it.

There’s a lot going on here, but let’s start with the obvious:

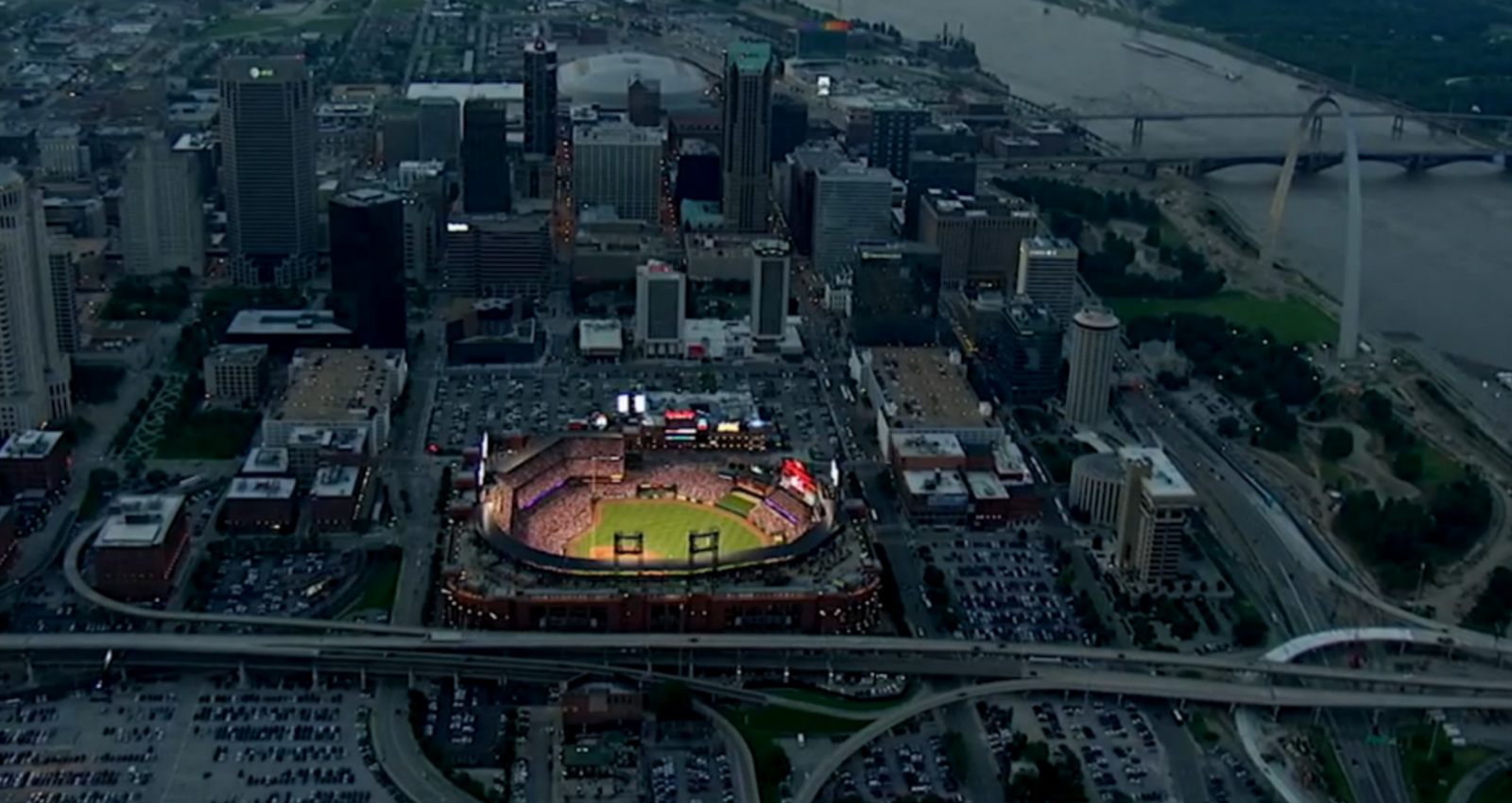

The $411 million privately-financed stadium was unique. In an era when most sports facilities relied on public funding, the St. Louis Cardinals privately financed the new ballpark, covering 90 percent of the cost.

Even in the most charitable possible interpretation, this claim is preposterous. Let’s add up the direct and indirect sources of funding Busch Stadium III received from the public:

- A 25-year City real estate tax abatement worth roughly $20 million.

- A $45 million loan from St. Louis County, raised by the sale of bonds that are being repaid over 30 years at a total public cost of $110 million.

- $29.45 million in tax credits from the state of Missouri.

- $12 million in funds from the Missouri Department of Transportation.

We’re already at $107 million—more than a quarter of the $411 million cost that the Cardinals would like you to believe was 90% privately funded—and we haven’t even gotten to, by far, the biggest source of public funds the Cardinals received: the permanent abatement of the five percent City amusement tax previously applied to ticket sales.

This was a massive giveaway. The Cardinals’ gate receipts totaled $129 million in 2015 and have risen by an average of three percent annually over the last ten years; assuming that rate remains constant, the elimination of the amusement tax will put an extra $237 million in the Cardinals’ pockets over the stadium’s first 30 years of operation.

This was a key component of the stadium deal, and Bill DeWitt’s ownership group extracted it from the city the same way every team owner in history has obtained public stadium financing: by threatening to move. For years leading up to the agreement that was reached in late 2002, the Cardinals actively courted stadium proposals from the County, St. Charles, and the Metro East, among others. A Post-Dispatch report from May 2002 described the state of play as the team’s presence in downtown St. Louis hung in the balance:

The Cardinals hope that they’ll benefit by a bidding war between area communities eager to be the site of the team’s planned new ballpark to replace 36-year-old Busch Stadium. …

[Mayor Francis] Slay and his aides fear that the Cardinals’ departure could touch off a new urban exodus that could derail already precarious efforts to resurrect downtown and rescue city neighborhoods. Losing the Cardinals “would be a terrible, terrible blow,” [Jeff] Rainford said. …

[Cardinals President Mark] Lamping hinted Friday at his news conference at one matter that the team wants to see the city put on the table. The issue: Cutting the city’s 5 percent amusement tax that’s tacked onto every ticket.

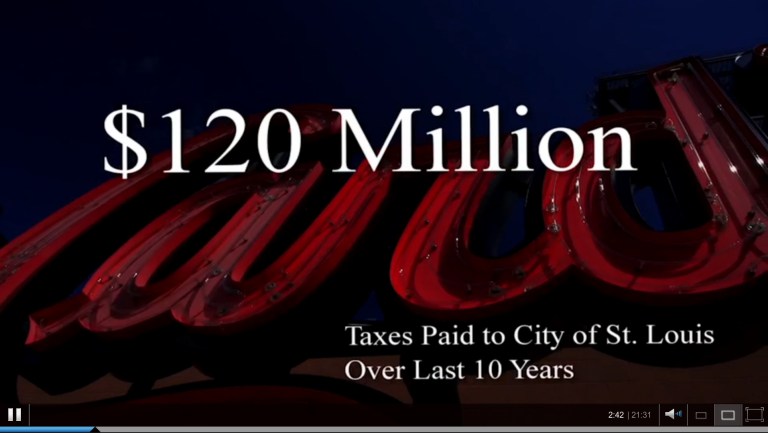

The city paid the ransom, at a cost of about $60 million and growing. Keep this concession (and the way the Cardinals obtained it) in mind when considering the video’s claims about taxes paid to the city, which it says leapt from $7.7 million per year “before the new ballpark agreement” to $12 million after. That’s some very careful language there; a page on the Cardinals’ website provides a bit more detail for this claim, specifying that the $7.7 million figure is an average of taxes paid between 1997 and 2001, before the stadium deal was struck in 2002—conveniently attributing five years of inflation and growth between 2001 and 2006 to the impact of a new stadium that hadn’t been built yet. Figures for the years immediately prior to the stadium’s opening, which would be most relevant to determining its impact, are conspicuously absent.

There are other reasons to be skeptical of the video’s tax claims and the implication that the new stadium is wholly responsible for increased revenues. The MLB-average Fan Cost Index, which tracks concession and merchandise prices, has risen at a substantially higher rate than inflation since 2000, meaning that sales tax revenues from Cardinals games would’ve seen a significant boost with or without a new stadium. The same is true of taxes applied to the team’s payroll, which like others throughout the league has risen thanks in large part to big-money TV rights deals. And it’s unclear whether the figures include sales tax revenue from Ballpark Village, much of which, many believe, is simply being siphoned off from other downtown businesses.

___________________

Speaking of Ballpark Village—at first glance, it seems a bit odd that in a video touting Busch Stadium’s positive economic effects on downtown St. Louis, BPV is mentioned only a few times in passing. But maybe it’s not so odd at all.

While study after study has debunked the notion that publicly-financed sports facilities can be engines of economic growth for metro areas as a whole, the literature does suggest that stadium projects can help achieve revitalization at the district level—an appealing prospect for a city whose real-estate assets are as scattered and misallocated as St. Louis’ are. A 2004 study in the Journal of the American Planning Association concluded that “sports facilities can play a role in urban revitalization efforts, catalyzing district redevelopment in the form of hotels, residences, and retail businesses.”

From the very earliest whispers of a new Cardinals stadium, the team held up Ballpark Village as a key benefit the city would receive in exchange for public funds, and support for any deal was highly contingent upon the project being realized. “The Cardinals’ pitch for a new, publicly financed stadium,” wrote the Post-Dispatch in 2002, “depends heavily on the prospects for Ballpark Village, the adjoining commercial and residential development that would give the project more bang for the buck.” Here’s how the Cardinals themselves described BPV in a full-page ad in the Post-Dispatch during a 2001 PR blitz:

The ballpark proposal is about more than just building a new home for the Cardinals and their fans. It’s also a sign of our commitment to downtown. That’s why a key part of our plan alse deals with the area surrounding the ballpark itself. Ballpark Village is an entire residential, business and entertainment district that will help spur economic revitalization in downtown St. Louis. Current plans include a spectacular new Cardinals baseball museum, a world-class aquarium, offices, retail shops, restaurants and 400 residential units.

The project, of course, was first put on hold and then dramatically scaled down before finally opening in 2014—with the help of another $17 million in tax credits from the city and state to cover infrastructure costs. The $100 million development (down from a planned $650 million) is still quite wishfully described as “Phase One”; whether subsequent phases ever going to happen is anyone’s guess. What’s certain is that ten years on, the “entire residential, business and entertainment district” that the Cardinals promised in order to garner support for a stadium deal is nowhere to be found.

Busch Stadium III is a gorgeous ballpark and a great asset for downtown St. Louis and the city as a whole. As far as stadium deals go, it wasn’t an egregious fleecing on the order of, say, the Braves’ new Cobb County home or the Rangers’ $1 billion replacement for their 22-year-old ballpark. But that doesn’t make the Cardinals’ math here any less fuzzy, and it certainly doesn’t erase their well-documented history of extracting major concessions from the city and making as-yet-unfulfilled promises about what the public would receive in return. The new Busch may well deserve to be commemorated, but there’s work left to be done, and the Cardinals shouldn’t take a victory lap they haven’t fully earned.

___________________

This post first appeared on the double-birds.com website and is reposted with permission from the author.