This post first appeared on the excellent Broken Sidewalk site. It is reposted here with permission from the author.

On Thursday morning, Mayor Greg Fischer and officials from Metro Louisville unveiled the year-and-a-half late transportation plan, Move Louisville. In the report, the city issued two major priorities to guide transportation spending and policy in Louisville in coming decades: to maintain existing infrastructure ahead of building new and to significantly reduce the vehicle miles traveled by Louisville motorists.

“Move Louisville takes a holistic approach to our transportation system,” Mayor Fischer said at the plan’s unveiling. He said the city’s existing transportation system is valued at $5 billion, making it an asset worth maintaining—one of the city’s main talking points. “We have two top priorities,” the Mayor continued. “The first we call ‘Fix it First.’ That is fixing our existing infrastructure so we can maintain what works best. The second is reducing the number of miles that Louisvillians drive. We’ll do that by increasing the number of mobility options.”

And the mayor plans to reduce the vehicle miles travelled (VMT) in Louisville by a significant number. In Jefferson County in 2014, motorists travelled over 7 billion miles—that’s enough miles to travel to the moon and back 15,211 times. The equals out to more than 19,178,082 miles each day (42 trips to the moon and back). Move Louisville suggests a reduction in VMT by roughly one trip to the moon and back—500,000 miles—or 2.6 percent or the daily miles driven in Louisville. But over a year those miles add up: a daily 500,000 mile reduction equates to 182,500,000 miles (397 trips to the moon and back). That’s not pocket change.

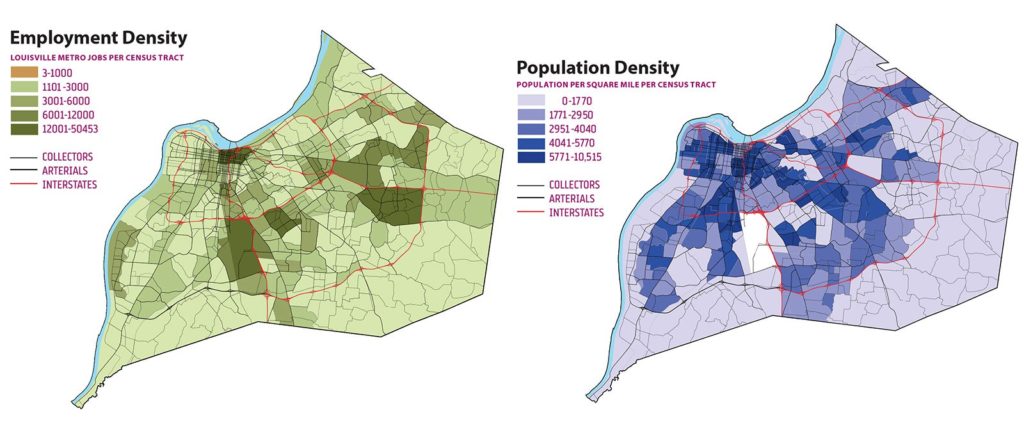

To achieve that reduction, Move Louisville is focusing on the shortest trips that can easily be converted to walking, biking, or taking transit. According to the document, 50 percent of all automobile trips made are three miles or less, with 28 percent of trips being a mile or less. Those trips, especially in the latter category, should not involve driving an automobile.

Move Louisville also delves into more systematic ways to reduce driving, including meaningful investments in transit, promoting mixed-use, walkable nodes of development, and building complete streets to make walking and biking easy and safe. But those projects, while the most likely to affect change, are also among the most difficult to actually get built.

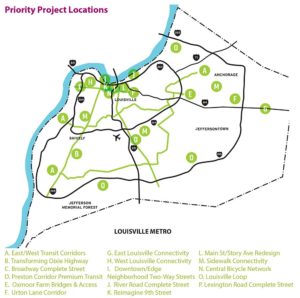

To meet these goals and others, Move Louisville lists 16 priority transportation projects valued at $762 million and eight policy priorities to guide the city through 2035. The report lists a number of recommendations, from increasing street safety to finding alternative funding mechanisms for increased transportation spending.

To meet these goals and others, Move Louisville lists 16 priority transportation projects valued at $762 million and eight policy priorities to guide the city through 2035. The report lists a number of recommendations, from increasing street safety to finding alternative funding mechanisms for increased transportation spending.

But one of the biggest benefits of Move Louisville is that it exists at all—many transportation grants require such a plan as a base requirement. A plan of this scope is a major achievement—one that Louisville Forward Chief Mary Ellen Wiederwohl said was worth taking extra time to get right. “It is a very complicated and expensive plan,” Wiederwohl said at a press conference Thursday. “So before we rolled it out, we wanted to be really sure we understood how much it would cost, what the various options would be.”

Move Louisville is filled with ambition for a multi-modal city that can bring about a healthier Louisville with more and better options for residents. It calls for significant increases in transportation spending to maintain the city’s crumbling infrastructure and to build new projects. The plan is certainly no small undertaking. But does it go far enough and call for the change we really need in Louisville right now? Let’s dig in.

Is Move Louisville strong enough?

Reading through the Move Louisville plan, it’s easy to become enamored with the 16 priority projects. Were they to be implemented overnight, Louisville would be a very different place. One where walking, biking, and transit, while still not equal with automobile transport, would at least be more convenient, more respected mode choices. And Louisville would be a healthier place with fewer people driving, especially for short trips.

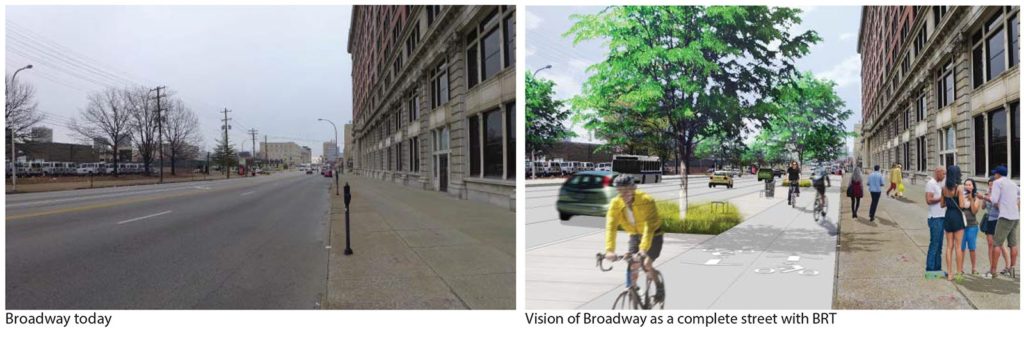

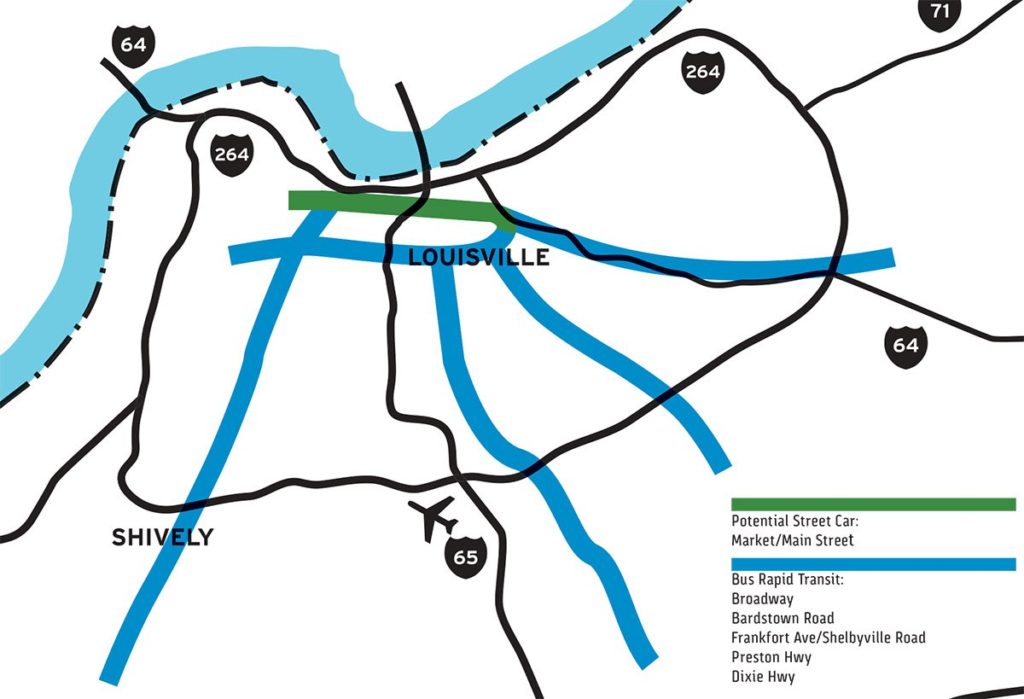

The report details proposals like highway removal at Ninth Street, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) along major arterials, expanding Louisville’s bike and pedestrian networks, and pushing complete street principles to the fore of roadway design.

But as I read and re-read the Move Louisville report, I’m left wondering how much of this is actually achievable. There are a lot of unanswered questions, questionable proposals, and few teeth behind much of what is being offered.

Now don’t take this as a dismissal of the plan outright, I would certainly love to see Move Louisville’s vision take shape and be implemented. But it’s going to be very difficult for Louisville to live up to the lofty aspirations of a dozen prized transportation projects. Louisville has some major challenges when it comes to transportation, and any significant improvement will be tough, will require fearless leadership, and will require taking on the status quo head on.

The reality is that Louisville is already a decade behind other cities in realizing these priorities. We’re trailing peer cities in metric after metric when it comes to livable streets, transit and bike ridership, and healthy lifestyle, and Louisville needs strong leadership and a heavy dose of reality to quicken our pace and catch up. We can’t wait until 2035 to be where the competition already is today.

Facing a stark reality

To get a better picture, it’s important to know the situation on the ground, and Move Louisville does a terrific job documenting what we’re up against. Let’s take a look.

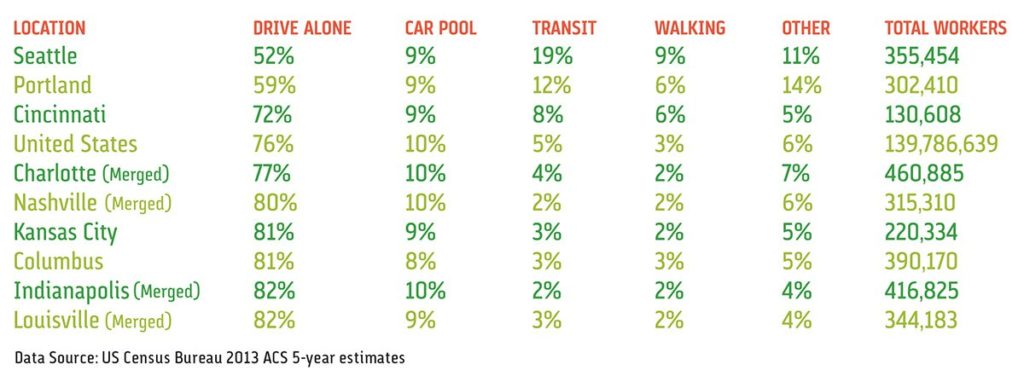

Move Louisville puts data behind what we already know: Louisvillians drive—a lot. “In comparison to our regional peer cities and the nation, Louisville’s percentage of residents driving to work alone is high,” Move Louisville reads. Almost 82 percent of Louisville’s 344,000 workers drive to work alone each day. “For example, 72% of Cincinnati’s residents drive alone, while Nashville’s and the nation’s rates stand at 80% and 76%, respectively.” Some 89 percent of Louisville households have one or more automobiles.

And that’s impacting the city’s air pollution. “In Jefferson County, on road sources—cars, trucks, buses, etc.—are responsible for up to 35% of the emissions of NOx and roughly 20% of the emissions of VOCs (the two compounds that combine to produce ground-level ozone),” Move Louisville reads. “Poor air quality in our urban areas is linked to increases in asthma and other illnesses. Yet if each resident in a community of 100,000 replaced one car trip with one bike trip just once a month, it would cut carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 3,764 tons per year in the community.”

At the other end of the spectrum, only three percent of people in Louisville take transit to work. That’s only 10,320 people out of Metro Louisville’s pool of 344,000 workers. Locally, ten percent of households do not own a car, making them reliant on transit, biking, or walking.

But worse, owning a car is causing economic hardship for the majority of Louisville households. Move Louisville reports that 66 percent of Louisville households that own cars are paying more than 45 percent of their income to housing and transportation. That places “a significant cost burden on low and moderate income households.”

These are serious obstacles that impact the health and quality of life of Louisville citizens and the environment in which they live. They’re going to require leadership to recognize the problems, explain the grim situation to the population, and push for change in a timely manner.

A road-building binge

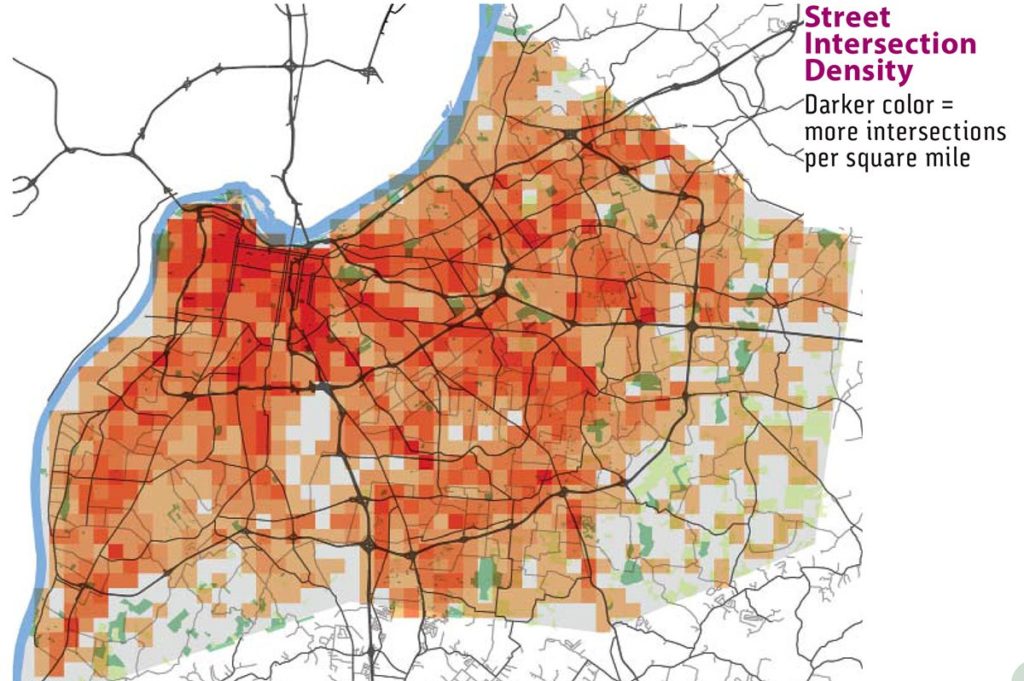

Move Louisville continues with more cold facts. Louisville, with the help of the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, has been on a spending spree of new roads for over half a century as the city sprawls ever outward. Other cities have long been curtailing that expensive and destructive trend. According to Move Louisville, “in 2012, pavement and bridge preservation allocations accounted for 43% of the total funds administered by Indianapolis. By comparison, 15% of the funds programmed in Louisville’s TIP are devoted to system preservation.”

“The majority of the regional transportation funding continues to be applied to new roadway construction or capacity projects with $37.4 million (61%) programmed for these projects in the 2015-2018 TIP,” Move Louisville reads. “These programmed funds include federal, state and local transportation appropriations. Prioritizing capacity and expansion projects over system preservation compounds the maintenance problem.”

Demonstrating just how overbuilt the city’s automotive infrastructure is today, Louisville’s motorists generally have half the commute time of a Louisville transit rider. “Average commute times in Louisville are fairly low, with nearly 67% of the workforce taking less than 25 minutes to travel to work,” Move Louisville reports. “For those who use public transportation, commute times are longer; with over half of the workforce taking public transportation reporting that their travel times to work took 45 minutes or longer and nearly 36% reporting commute times of over one hour.”

For transit to be a viable solution, it’s got to be the most convenient one. You’re not going to convince someone to get out of his or her car and stand by a pole on the side of Shelbyville Road on an unsheltered patch of dirt to make an hour long commute to work—or to run a short errand. They’re going to continue using their cars because that’s the system we’ve invested in for more than 60 years at the expense of all others.

More subsidy for sprawl

The mayor’s “Fix-it-First” priority is certainly a welcome policy. “Meeting the Move Louisville goals requires a substantial investment in maintaining the operational functions and physical infrastructure of the system,” the report reads.

Move Louisville estimates that the region’s current maintenance deficit is $288 million. According to the city, it will cost $112 to repair the 30 percent of city streets rated as deficient, with another $27 million required to rehab bridges and culverts. To fix Louisville’s sidewalk network, it will cost far more: $86 million is required to repair ten percent of the city’s existing 2,200 miles of sidewalks and another $112 million to fill in gaps in the sidewalk network—many of which create extremely dangerous situations for Louisville pedestrians.

Annually, Louisville faces an on-going maintenance cost of $17.75 million, with $17.5 million going to repaving, bridge/culvert rehab, and signage, striping, and traffic signals. Only $250,000 annually—1.4 percent—goes toward sidewalks, which will require $198 million to bring into good repair.

The plan recommends reallocating our current funding model to tackle maintenance and build the priority projects at a cost of $69.7 million annually over the next 20 years. “These recommendations represent a significant shift away from road capacity projects and seek to enhance system preservation, improve road operations, implement complete streets and enhance transit and active transportation modes,” the report said.

{One of Move Louisville’s priority projects is building roads to assist in developing this rural part of Jefferson County}

{One of Move Louisville’s priority projects is building roads to assist in developing this rural part of Jefferson County}

But that doesn’t mean Louisville won’t continue to build sprawl. Move Louisville states that it would allow “for enhancement and expansion projects to be brought on board as funding allows.” That’s the standard road building practice we’ve been stuck with for decades. Further, three of Move Louisville’s 16 priority transportation projects—comprising a full third of the cost for all 16 priorities—call for new road building on the edges of Jefferson County to promote more development in the hinterlands.

Those three projects are the $160 million “East Louisville Connectivity” proposal that would expand an interstate highway and build new roads to accommodate development in one of the last rural parts of the county:

The rapidly-developing area around the newly opened Parklands of Floyds Fork will bring network connectivity issues. Transportation should be addressed holistically to accommodate new development and all modes of travel where appropriate. It is anticipated that many of the larger projects will be focused on Interstate improvements. For example, a new interchange and connector road from KY 148 to US 60 (Shelbyville Road) on I-64, will greatly increase accessibility. Strategically improving existing rights of way and building a limited number of new connector roads will accommodate access to the Parklands of Floyds Fork and adjacent areas.

The $40 million “Urton Lane Corridor Improvements” proposal that would build a new road through farmland near the Gene Snyder / Interstate 265 to speed up automobile travel times:

Completing the planned extension of Urton Lane from Middletown to Taylorsville Road, will provide a long-needed local thoroughfare expediting the movement of goods and services and facilitating shorter and more efficient commutes for residents working and doing business in the area.

And the $54 million “Oxmoor Farm Bridges and Access” proposal that would seek to develop a large farm behind Oxmoor Mall by paying for new roads and bridges into the area:

Transportation infrastructure is the key to unlocking this ideally situated undeveloped parcel of land. With multi-modal streets and a planned mixed-use, multi-generational dense development, this site – the largest of its kind in the city – could be transformed into a district of superior urban quality, livability and accessibility. New bridges and roads also have the potential to ease congestion in the area and provide new connectivity points. A mixed-use development plan has been approved for the site. Public investment in the infrastructure for this opportunity should be linked to significant density and a mix of uses.

With 20 percent of Move Louisville’s priority projects certain to create more sprawl and dependence on the automobile, something isn’t right.

I put the question to Louisville Forward Chief Mary Ellen Wiederwohl on Thursday: “We’ve got to do it all to remain economically competitive and provide that high quality of life for the talent we want to attract,” she said. “We’ve got to protect this $5 billion asset we have and then plan for the areas where we can grow intelligently.”

In his introduction to Move Louisville, Mayor Fischer wrote, “Balancing the needs of the system over our nearly 400 square miles means that difficult choices must be made.” The number one difficult choice must be to stop spending public money to help develop greenfields out in the suburbs.

Will Frankfort buy in?

One of the biggest uncertainties in the Move Louisville plan is whether any of its lofty ideals will be able to take root along the city’s state-controlled arterial network.

To start out, the Move Louisville plan gets the language right:

In Louisville the mix of higher speeds and pedestrian activity is most prevalent along the larger arterial streets that lead from the suburban communities into downtown (Dixie Highway, Preston Highway, etc.). These arterial thoroughfares have been designed for high speeds and traffic volumes. As the context of these thoroughfares change (sic) over time, such as to walkable, compact mixed-use areas, the speed encouraged by the design becomes a matter of concern. Higher speeds result in a higher percentage of injury and fatality crashes. By reducing speeds through enforcement, design and technology, and adding enhancements for the comfort and safety of all users, a balance can be achieved between moving cars and moving people.

But the KYTC has repeatedly stymied efforts in Louisville to slow down traffic, redesign streets for people, add bike facilities, or make even the slightest change to its network of high-speed arterials through our local neighborhoods.The state agency is concerned, first and foremost, with engineering streets for the efficiency of moving cars quickly. Everything else has taken a back seat.

Still, Mayor Fischer remained optimistic when asked about this concern at Thursday’s press conference: “We are somewhat unique compared to the needs of rural areas of the state,” Fischer said. “Having a state transportation department that thinks about the unique needs of the city is critical. We’ve seen progress in that in the last couple years, but that will be another area of emphasis.”

Fischer said that the Move Louisville plan would go a long way toward convincing state engineers of the efficacy of Louisville’s multi-modal goals. “For us now to have a plan that we can go and talk to them about specific projects is important,” Fischer continued. “As they become more specific we anticipate we’ll have good teamwork along the way.”

But Move Louisville is a local plan crafted at the municipal level. No state officials were present at its unveiling and none were on the Move Louisville Project Team (although three KYTC representatives were on its advisory committee). We’re rooting for Metro Louisville to reform KYTC’s views of urban roadways, but the evidence to support such a change is simply not there.

Beyond shifting the paradigm on street design, Metro Louisville must also convince KYTC to change its long-standing protocol for funding transportation projects. “It might be radical for what we’ve done in this state, but it’s certainly not radical for what’s going on in other cities and other states,” Fischer said. “It’s about talking about each of the projects and the principles we have in place. They know we’re a different kettle of fish here in Louisville. It’s a stage that we have to move through.”

Fischer cited pending changes to the Dixie Highway corridor as a success story for working with the state to achieve local safety goals. “You can see how we’ve had success in that area when we take on projects like the Dixie Highway Do-Over—a big project, broken down into three parts, the state involved in each of those parts, the federal government involved in the TIGER grant,” Fischer said. “That’s how we’re going to have to approach all these different projects.”

Louisville would do well to establish some kind of local control from the state of all surface roads in the city. We shouldn’t have to go to the state to explain the nuances of each little project or change we want to make to get an out-of-towners blessing on making our neighborhood streets safer. Creating a protocol where Louisville can make changes to its own streets on its own terms should be a priority if we’re to take street safety seriously.

Complete Streets

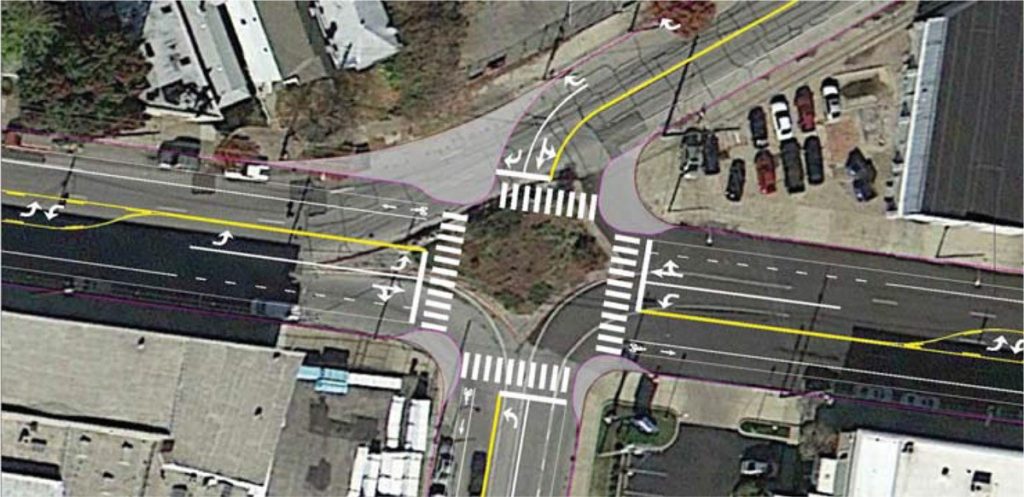

{Diagram of a redesigned intersection of Story, Main, Mellwood, and Baxter}

{Diagram of a redesigned intersection of Story, Main, Mellwood, and Baxter}

Among the goals of Move Louisville is to make complete street principles the norm as we recreate our transportation network. Another great proposal from the plan. But that’s easier said than done.

Louisville published a detailed, 156-page report titled the “Metro Louisville Complete Streets Manual” in 2007 and has had a complete streets ordinance on the books since 2008 that requires new streets and street retrofits to incorporate complete street principles. But in the past decade, Louisville has fallen short on delivering meaningful complete street coverage, as detailed in a recent op-ed by Bicycling for Louisville President Chris Glasser.

“The impact of the ordinance has not been robust both because the Louisville Land Development Code was not updated to include complete streets requirements for private development and new innovations in bicycle facility design have occurred since the ordinance’s passage,” Move Louisville wrote. But given the ease of acquiring sidewalk waivers and the “flexibility” with which we treat the land development code, it’s unclear whether that would have actually made a difference.

Still, it’s better that complete streets are codified in the most efficient way to bring about their implementation. “The next steps are to update the street design standards and the Louisville Development Code to implement the desired complete streets outcomes,” Move Louisville continued. “These steps should be part of a formal Complete Streets Implementation Strategy.”

With Louisville’s complete streets strategy clearly not working today, I asked city officials what needed to change to make it “the norm” as Move Louisville hopes to do. “We as Metro Government need to put a working group together,” Jeff O’Brien, deputy director of advanced planning at Develop Louisville, said. “We are looking at the way we currently accomplish road infrastructure projects. It’s really taking our existing resources and looking at them holistically and making sure that when we make these decisions on where bicycle facilities and sidewalks and road paving projects go, that we are looking at the range of users and the range of options we have for reallocating our rights of way.”

Will there be citizen demand?

With everything Louisville is up against when it comes to transportation, strong leadership is needed to guide the city through these shifts in practice and policy. The potential backlash against some of these proposals is real, and our leaders must keep the city on course.

Luckily, Mayor Fischer did just that at Move Louisville press conference when asked how he would respond to motorists upset that an emphasis on pedestrians and cyclists would slow down their commute. “Our data shows that’s not the case,” said plainly, dismissing the criticism. “You’ll recall all of the consternation over the diet of Lower Brownsboro Road… The data that we have now shows it’s a safer road and the commute hasn’t changed in any kind of material way. People will have to adapt, there’s no doubt about that.” It’s this kind of leadership we hope shines through as Move Louisville progresses.

But during the present 60-day comment period, it’s citizen demand that will be responsible for determining what parts of Move Louisville are prioritized. And given the way some developments have recently played out in this city, perhaps politicians need this type of hands-off period to fend off the notion that Metro Louisville is forcing people out of their cars and onto the bus. “This plan is not anti-automobile,” Fischer said. “It’s a forward-looking plan for the 21st century.”

But that adds a new level of uncertainty to some of Move Louisville’s most forward-thinking ideas. Will the public in a city so set it its ways about driving rally to fund transit and make streets safer for everyone? Even if it means they themselves might need to drive less or pay more for parking?

We certainly hope Louisvillians will see the overwhelming benefits of the ideas presented in Move Louisville and how they can benefit everyone in the community—whether you’re on foot or behind the wheel. And to that end, we hope that you will take the time to submit a comment in favor of reshaping Louisville’s transportation system in many of the ways Move Louisville suggests.

“What we really need to hear right now from citizens is, ‘hey, we need this stuff’,” Fischer said. “The kind of demand we get from citizens, or lack of it, will encourage or discourage Metro Council from seeking additional forms of revenue.”

Conclusion

So you made it through all of that—well done. We’ve spent so much time analyzing the Move Louisville report only because it’s such an important document for the future of the city. And like Louisville Forward, we want to see it done right as well. Move Louisville is not a perfect plan, but it is a good start—and a major leap forward in terms of visualizing what a progressive set of priorities Louisville needs to be competitive in its future and healthy and safe for its citizens at home.

I support the Move Louisville plan, and I hope we accomplish most of what’s laid out in its 110 pages (but please not those three sprawl-building projects!). I hope that the city can work with the state to figure out how to redesign Louisville streets to be safe for everyone. It’s important to understand, after all, that arterials run through neighborhoods just like any other street. They should add to the neighborhoods they pass through rather than be treated as open sewers for vehicle traffic.

It’s clear that Mayor Fischer and his team at Metro Louisville understand that change is needed. And they know how to put it in terms of economic development to create multiple stories about why infrastructure is important. “We’re competing for talent and business with other cities,” Fischer said. “And as you travel around the country, you see all types of investment in the types of proposals we’re putting forth in this plan. If we want to keep our economic momentum going, we have to do likewise.”

But those cities currently building the proposals just made public in Move Louisville have a significant head start, and it’s time Louisville catches up. It won’t be easy, cheap, or sometimes politically palatable, but it’s imperative for the future of the city.

Don’t get distracted by Move Louisville’s hints at streetcars or the plans shunning of light rail. Louisville has a long way to go and those conversations will inevitably resurface as progress is made. Bus Rapid Transit, when implemented correctly, can be a transformational project for a city. But even before that, we need to have some serious discussions about fully funding TARC and investing in transit infrastructure—from shelters to sidewalks to service frequency—that will make the option attractive enough to get people out of their cars. That, in itself, could easily stretch on for 20 years. But Move Louisville looks much further, and I hope it succeeds.

This analysis covered some of the highlights of Move Louisville and some of its potential pitfalls, but there’s much more to the plan that we didn’t have time to discuss, from parking to transit policy to logistics and activity nodes. Those are just as important to get right as reducing the number of miles Louisvillians drive, and we’ll get to them in time. But for now, please take time to offer your feedback to the city on the Move Louisville plan.

______________

Editor’s note: An in-depth analysis such as this of a metro area with many similarities to St. Louis offers insight into how other places are choosing to address long term transportation planning. Both similarities and differences in planning and rhetoric is informative. The full PDF plan document and nextSTL commentary on the analogous St. Louis plan can be found here: “Connected2045 Long Range Transportation Plan for the St. Louis Region“.