This is going to sound a bit strange, but I sure do love roads.

That’s right, roads. And by “roads”, I mean the streets, avenues, and parkways all of us frequently drive, bike, or walk on to get around this city. I believe roads play an integral part in delivering good history. A few years ago, when I first thought about looking into the story of this town, my first step was to get out and get lost on the streets of St. Louis.

Think about it. In nearly every situation, a road, a street, a railroad track, a river, or even a foot path must exist in a place before history can happen there. The Mississippi River, which is essentially a road for vehicles that float, is a perfect example. The Mississippi River is the road Pierre Laclède and August Chouteau used to get to the place where St. Louis would come to be.

Perhaps a more practical example is St. Charles Rock Road, which was the first road (or more specifically, the first trail) that connected St. Louis to another early Louisiana Territory settlement, St. Charles. At first, this road was called “King’s Highway”. After it was macadamized in the mid-19th Century, it was called the “Rock Road”. Today, most of Missouri refers to it as Route 180. In St. Louis City, it’s called Martin Luther King. All of this is a great example of how even the name of a road can provide a good story. But in this case, St. Charles Rock Road gives us good history. That’s because in the early frontier days, driving St. Charles Rock Road was a necessary step for getting pioneers from St. Louis to St. Charles, and then on to the Oregon or Santa Fe Trails.

That’s a pretty big deal. And it got me thinking.

I wondered if I could effectively research and write about the history of a single road in St. Louis. I figured if I picked a nice long one, it would provide a good backdrop (and a good path) to finding good history in St. Louis. Even better, long busy roads usually have plenty of bars and pubs. While poking around for some good St. Louis history, it’d be easy to take a break and have a drink or two.

Well, I must admit that I had a certain road picked out all along: Kingshighway Boulevard.

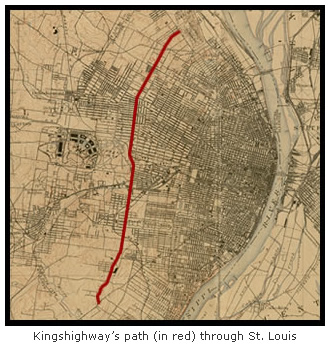

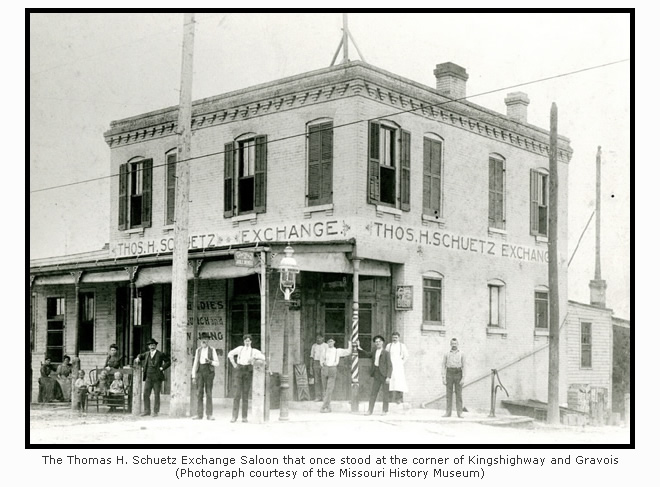

I’ve always been intrigued by Kingshighway, the nine mile boulevard that shares a name with that initial incarnation of St. Charles Rock Road. Kingshighway is a major north-south artery that cuts right through the western half of St. Louis. It lies entirely within the city, starting at Florissant Avenue in the north and ending at Gravois Avenue in the south. It’s rare for someone to ever need to drive or bike it from one end to another, but I’ve done it several times. I recommend others do it, because if someone travels those nine miles in one go, they’ll get a fascinating glimpse at the city of St. Louis as it looks today.

I’ve always been intrigued by Kingshighway, the nine mile boulevard that shares a name with that initial incarnation of St. Charles Rock Road. Kingshighway is a major north-south artery that cuts right through the western half of St. Louis. It lies entirely within the city, starting at Florissant Avenue in the north and ending at Gravois Avenue in the south. It’s rare for someone to ever need to drive or bike it from one end to another, but I’ve done it several times. I recommend others do it, because if someone travels those nine miles in one go, they’ll get a fascinating glimpse at the city of St. Louis as it looks today.

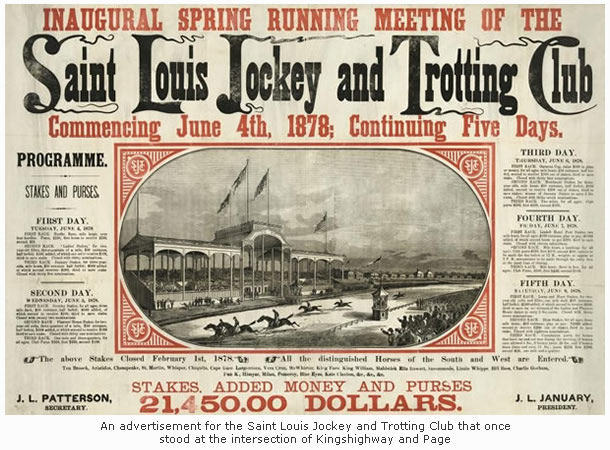

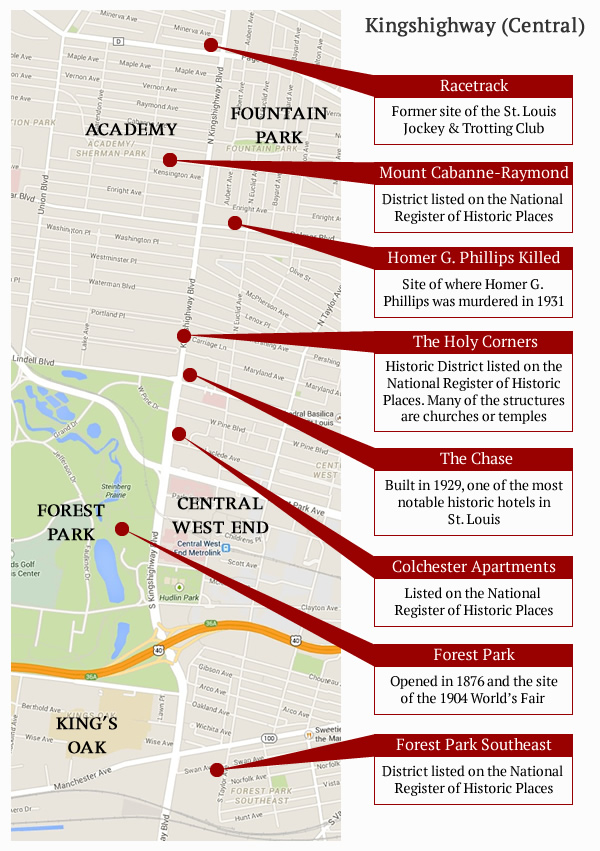

That’s because Kingshighway has a bit of everything. It cuts through or acts as a border for eighteen of St. Louis’s seventy-nine neighborhoods (that number may seem low, but few city streets can challenge it). It travels through struggling neighborhoods, affluent neighborhoods, and several others that fall somewhere in between. Drive it and you’ll see people of all color, shapes, and sizes. On a recent stop at the intersection of Kingshighway and Page, I even saw a clown. Kingshighway touches five city parks, nine entries on the National Register of Historic places, and dozens of other points of interest. Finally, Kingshighway boasts hundreds of homes, businesses, schools, and churches where thousands of people live, work, and play.

“King’s Highway” isn’t an uncommon name for a road. It’s been used all over the globe and throughout history as a name for a path on which people have traveled. The most famous being the ancient trade route between Syria and Egypt that is mentioned in the Old Testament. That King’s Highway is still in use today, making it about 3,000 years older than the version I’ve been driving, biking, and drinking along during the past few weeks. Other King’s Highways of note include King George II’s colonial highway that connected the American colonies and the 17th Century Spanish trade route that rambled all the way from Florida to Mexico. In fact, St. Louis even had two Kingshighways at one time. Union Boulevard used to be called “Second Kingshighway” until it was renamed in honor of the soldiers who fought in the Civil War.

“King’s Highway” isn’t an uncommon name for a road. It’s been used all over the globe and throughout history as a name for a path on which people have traveled. The most famous being the ancient trade route between Syria and Egypt that is mentioned in the Old Testament. That King’s Highway is still in use today, making it about 3,000 years older than the version I’ve been driving, biking, and drinking along during the past few weeks. Other King’s Highways of note include King George II’s colonial highway that connected the American colonies and the 17th Century Spanish trade route that rambled all the way from Florida to Mexico. In fact, St. Louis even had two Kingshighways at one time. Union Boulevard used to be called “Second Kingshighway” until it was renamed in honor of the soldiers who fought in the Civil War.

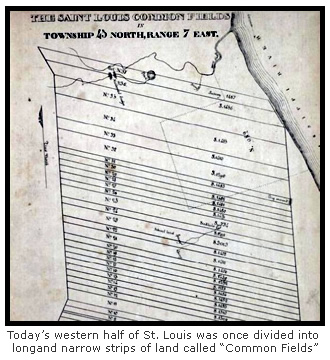

More than one story exists about how the St. Louis Kingshighway came to be. In the book The Streets of St. Louis by William Magnan, it’s detailed that St. Louis’s Kingshighway originated as an Indian trail that led to a portage on the Missouri River. It was known as the “King’s Trace” or “King’s Road” by early settlers, and the name is derived from the custom of naming public roads that connect a sovereign’s territory to outlying lands. In St. Louis’s case, those outlying lands were the common fields. Used for farming and raising livestock outside of the village, the common fields were long, narrow strips of farm land that radiated out to the west of St. Louis.

Various other sources also detail that when St. Louis was first founded, early French settlers referred to the road as the “Rue de Roi” (“Roi” meaning “King” in French). When the Spaniards took over, it became “El Camino Real”. And when Missouri joined the United States in 1803, the English translation of “King’s Highway” finally stuck. In the early 1900’s, the apostrophe and space dropped for simplicity and it became the “Kingshighway” we see on street signs today.

Another version of Kingshighway’s origin comes from a man named Charles P. Chouteau, a descendant of the co-founder of St. Louis, Auguste Chouteau. In 1895, Charles Chouteau explained to a local newspaper that Kingshighway did not originate as an Indian trail. He claimed it was created and even named by his own grandfather, a Frenchman named Charles Gratiot. A distinguished veteran of the Revolutionary War, Gratiot came to St. Louis in 1780. In 1785, he appealed to the governing Spanish authorities for a large tract of land west of the village. Thirteen years later in 1798, it was granted.

Another version of Kingshighway’s origin comes from a man named Charles P. Chouteau, a descendant of the co-founder of St. Louis, Auguste Chouteau. In 1895, Charles Chouteau explained to a local newspaper that Kingshighway did not originate as an Indian trail. He claimed it was created and even named by his own grandfather, a Frenchman named Charles Gratiot. A distinguished veteran of the Revolutionary War, Gratiot came to St. Louis in 1780. In 1785, he appealed to the governing Spanish authorities for a large tract of land west of the village. Thirteen years later in 1798, it was granted.

That sizable tract of land (over 6,700 acres) was henceforth known as the “Gratiot League Square”. On today’s map of St. Louis, several notable neighborhoods fit neatly inside it, including Dogtown, the Hill, Clifton Heights, and even my own neighborhood, Lindenwood Park.

(And for those interested, the pronunciation of Gratiot, at least in St. Louis, is “Grash-ut”. It’s another perfect example of how St. Louis repeatedly whiffs at pronouncing anything French.)

Gratiot’s acquisition was named after the man himself and the distance of one league (about three miles) that each side of the square measured. And in order to mark the boundary between his land and the common fields to the east, Gratiot laid out a new road. According to his grandson, he named it “King’s Highway” in order to “honor the reigning monarch” of Spain. Chouteau also suggests this regal name was slyly chosen in order to keep the Spanish authorities interested in helping pay for any maintenance or upgrades.

Gratiot’s acquisition was named after the man himself and the distance of one league (about three miles) that each side of the square measured. And in order to mark the boundary between his land and the common fields to the east, Gratiot laid out a new road. According to his grandson, he named it “King’s Highway” in order to “honor the reigning monarch” of Spain. Chouteau also suggests this regal name was slyly chosen in order to keep the Spanish authorities interested in helping pay for any maintenance or upgrades.

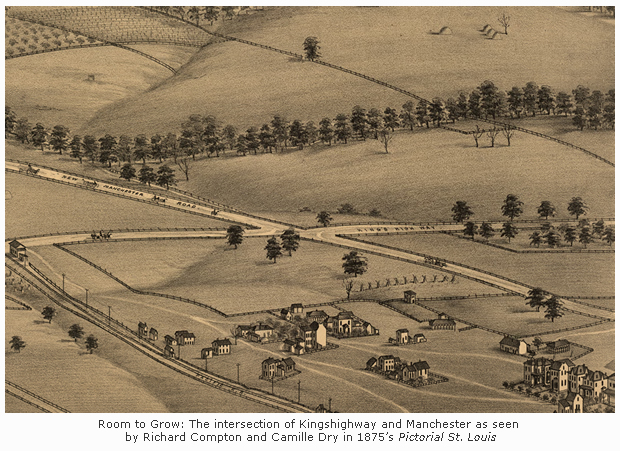

Whichever story of origin is true, it must be noted that Kingshighway has spent much of its history traveling through only sparsely developed areas of St. Louis. In fact, it didn’t even become part of the city until 1876 when the St. Louis city border was pushed westward from Grand Avenue to its current position just west of Forest Park.

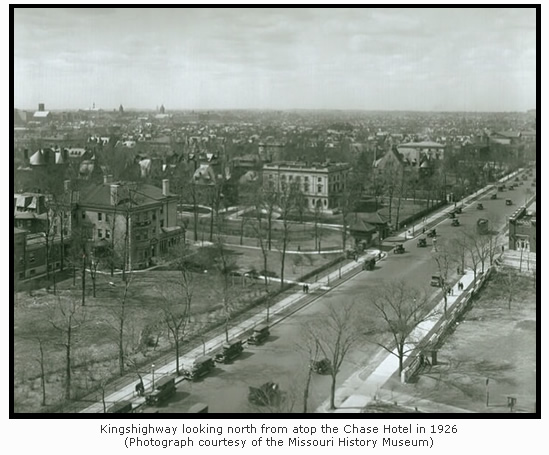

But unlike other north-south thoroughfares such as Grand or Jefferson, Kingshighway wouldn’t see much action until planning for the 1904 World’s Fair began. That’s when city planners suggested turning Kingshighway into a major artery for the developing western half of the city. In 1903, the King’s Highway Boulevard Commission was formed, a group that submitted an expansive proposal for Kingshighway redevelopment. Upon completion, supporters of the proposal claimed that St. Louis “will possess the longest and grandest boulevard in the world.”

At the time, only about one mile of Kingshighway (from Lindell north to Easton) was even paved. Mud and dirt made carriage travel difficult, with one newspaper account claiming that it was “impossible, in rainy weather, to cross King’s Highway without stilts”. Proposed improvements included grading, paving, and widening its entire length, building new bridges, adding decorative landscaping, and lining it with ornamental lampposts. Most significantly, Kingshighway was to be lengthened to nearly eighteen miles, reaching from a new park at the Chain of Rocks in the north to Carondelet Park in the south. Upon completion, a St. Louisan would have access to all four of the city’s major parks (O’Fallon, Forest, Tower Grove, and Carondelet) and it’s two major cemeteries (Calvary and Bellefontaine) from one single road.

Unfortunately, if turns out St. Louis wasn’t quite ready for the “Champs-Élysées of the West” as many hoped it would be.

Financial oversights and rising land costs delayed the project from the start. And despite popular approval, certain property owners were adamantly opposed to selling their land for the sake of a wider road. As a result, the plan became mired in courtrooms and council meetings. It would be twenty years before any actual work began. By then, many of the key proposals in the original plan were revised or even stripped out, including the proposal to extend Kingshighway’s length.

One proposal that did make the cut was the idea to build and upgrade smaller parks along the route. A major beneficiary of this was Penrose Park, a smaller park that sits on the east side of Kingshighway just south of I-70. It’s also worth nothing that one of the city’s most unique amenities exists here, the Penrose Park Velodrome. One of only twenty-seven velodromes in the United States, it offers a 1/5 mile cycling racetrack with forty degree banking.

Personally, my favorite (and most used) stretch of Kingshighway is the one I live closest to. It’s the southern section, stretching from Highway 44 to its southern terminus at Gravois Avenue.

The most significant part of this stretch sits on the east side of Kingshighway (across the street from the previously mentioned Gratiot League Square). This land, stretching from Kingshighway to Grand Avenue, was once known as the “Prairie de Noyers”. It was a common field used for farming and raising livestock, but that changed when valuable coal and clay deposits were discovered in the area in the mid-19th Century. A notable example of this is the strong Italian presence that still exists in the Hill neighborhood on the west side of South Kingshighway. It was the clay pits and brick plants that spurred Italian immigrants to settle in the area years ago. Today, we are still reaping the benefits from the community they created.

The most significant part of this stretch sits on the east side of Kingshighway (across the street from the previously mentioned Gratiot League Square). This land, stretching from Kingshighway to Grand Avenue, was once known as the “Prairie de Noyers”. It was a common field used for farming and raising livestock, but that changed when valuable coal and clay deposits were discovered in the area in the mid-19th Century. A notable example of this is the strong Italian presence that still exists in the Hill neighborhood on the west side of South Kingshighway. It was the clay pits and brick plants that spurred Italian immigrants to settle in the area years ago. Today, we are still reaping the benefits from the community they created.

But the most significant (well, at least in my opinion) event in the development of this area happened in the 1850’s when a man named Henry Shaw started buying strips of land in the Prairie de Noyers and converting them to what is essentially a giant, fantastic garden. As a result, St. Louis now reaps the benefits of Tower Grove Park and the world-renowned Missouri Botanical Garden. I’ve expressed my admiration for Mr. Shaw often in this blog (here and here), so it’s obvious that the road I often take to get to Shaw’s old stomping ground should get its own Distilled History post.

Another reason I prefer the southern stretch of Kingshighway is that it’s the only section where I can stop and get a drink. The northern section actually offers a restaurant specializing in tripe (yes, tripe), but it lacks a bar of any sort. The only option in the central section requires getting inside and navigating a luxury hotel (which didn’t stop me this time).

Another reason I prefer the southern stretch of Kingshighway is that it’s the only section where I can stop and get a drink. The northern section actually offers a restaurant specializing in tripe (yes, tripe), but it lacks a bar of any sort. The only option in the central section requires getting inside and navigating a luxury hotel (which didn’t stop me this time).

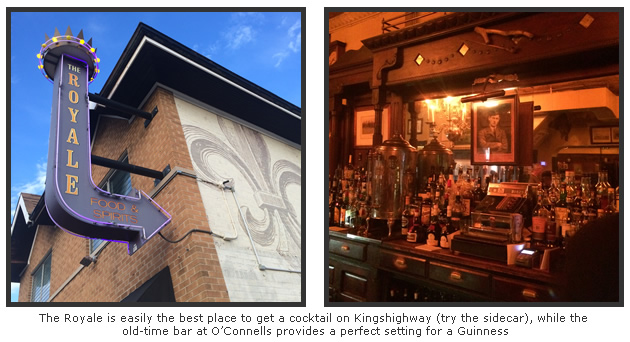

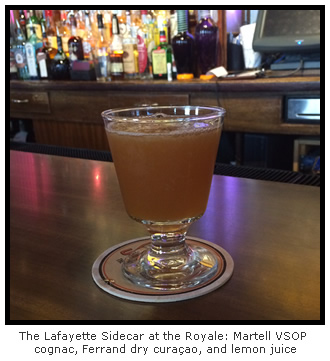

But the southern section provides a nice run starting with O’Connells and a well-poured Guinness at the intersection of Kingshighway and Shaw. Another mile or so to the south is The Royale, which is one of my favorite bars in the city. Not only is the name suitable (King’s Highway was also referred to as “Rue Royale” by French settlers), but the Royale offers a well-rounded drink menu that any beer or cocktail connoisseur will find appealing. For my Kingshighway tour, I enjoyed a perfectly prepared Lafayette Sidecar.

Only a couple other drinking options exist on Kingshighway (well, non-Applebees options), making it possible for someone to actually drink their way down Kinghshighway in one trip. I did just that, creating my own Kingshighway pub crawl at the same time I researched this post.

With that in mind, have I mentioned how much fun writing this blog is?

_____________________________________

This post first appeared on the award-winning Distilled History blog, where Cameron Collins explores the history of St. Louis and its modern cocktails. Please visit his site and read the great items he’s putting together about our city.