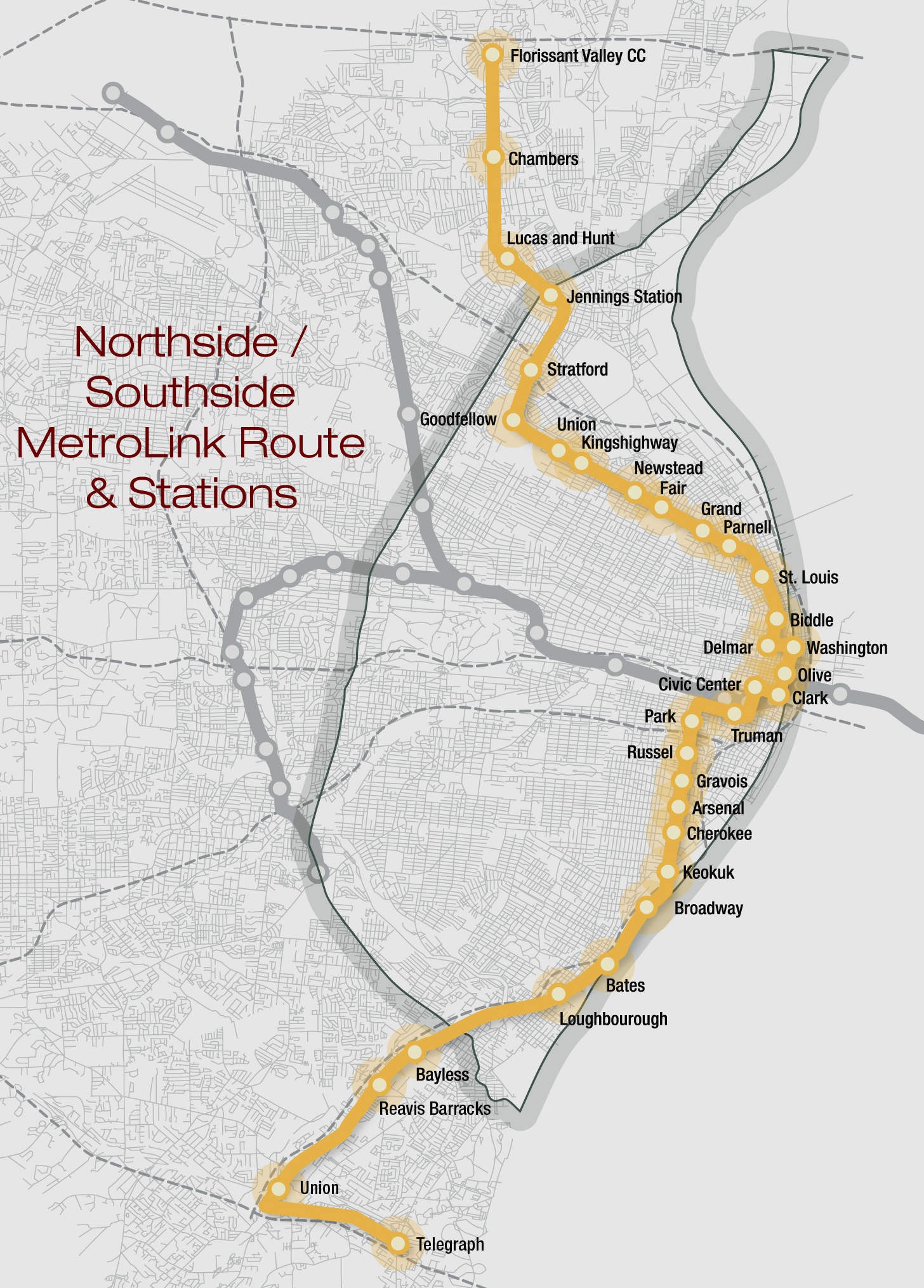

Earlier this year I wrote about the lack of a coordinated, consensus plan to expand transit within the St. Louis region. While different groups are pursuing a variety of projects, Northside/Southside MetroLink expansion remains the one corridor with the promise of transforming transit within the region. While the project has lacked a political champion, nothing else on the drawing board in the region comes close in terms of capacity to move people, stabilize population, and anchor redevelopment.

MetroLink has been a hugely successful endeavor and St. Louis residents want more of it. More than $15 billion in public and private investment has occurred around MetroLink stations since the first line opened in 1993. 60,000 people ride it every weekday, and 95% of people within Metro’s bus and rail system are traveling to school and work. MetroLink provides a spine which anchors the bus system.

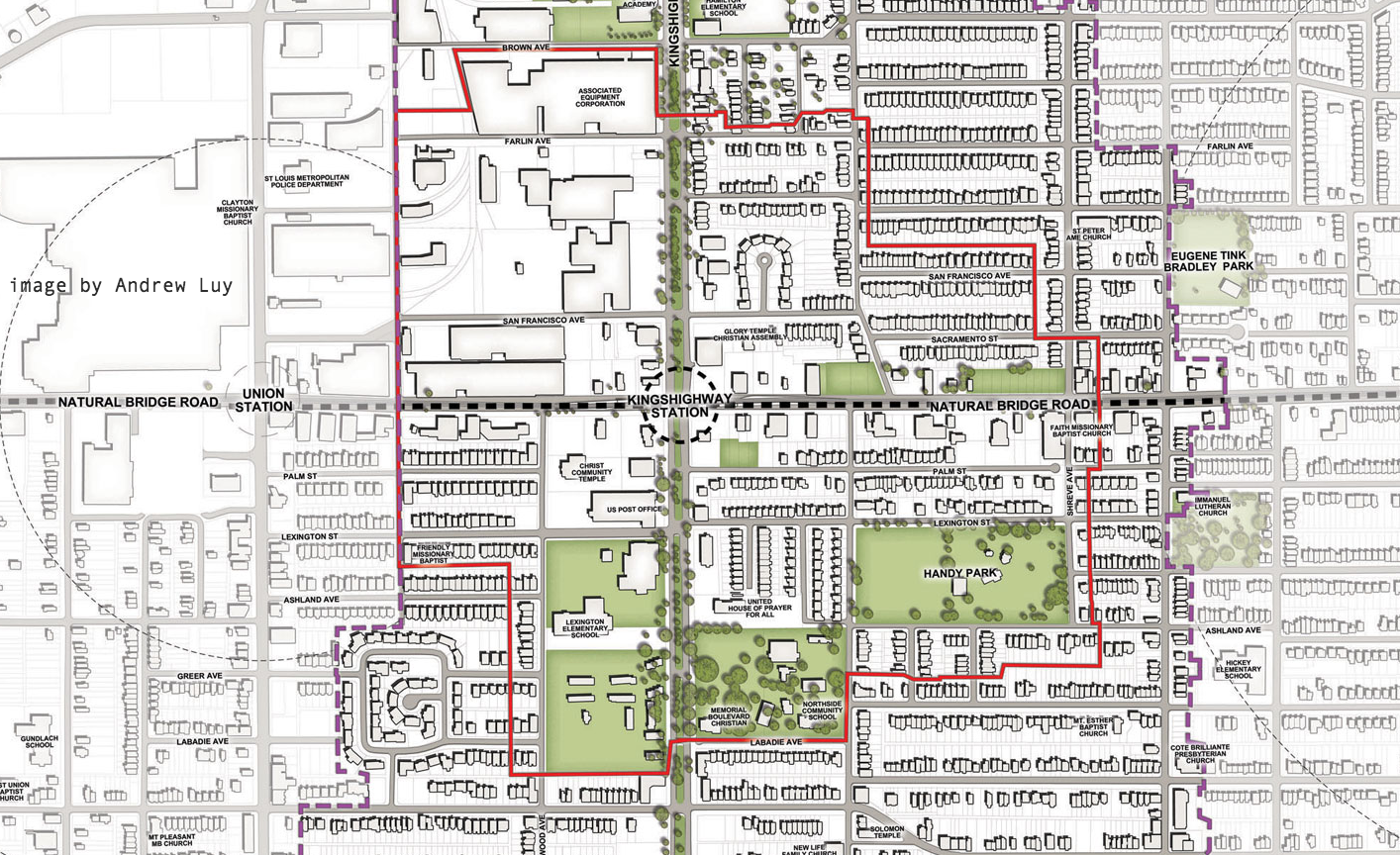

{envisioning a new future for a Kingshighway station in North City}

{envisioning a new future for a Kingshighway station in North City}

During the last census period between 2000 and 2010 within the City of St. Louis, only the central corridor, and specifically areas near MetroLink, (or about to be, like Cortex) added population. In St. Louis County a combination of bad zoning, misplaced incentives, and crummy municipal government have reduced the positive effect on neighborhoods that MetroLink could have achieved. Nevertheless, Clayton, Washington University, and UM-St. Louis are capitalizing on the Blue and Red lines in St. Louis County. Much more could be achieved along Blue Line with a change in development practices.

The MetroLink Red and Blue lines were never intended as an endpoint. These lines are the foundation of a more useful system. Transit benefits accrue faster and to more people when the network expands. 21 years after opening, MetroLink remains primarily an east / west system. The Northside/Southside line is like the roof over the foundation – it gets the region much closer to a complete system.

{envisioning a new future for a Natural Bridge station in North City}

{envisioning a new future for a Natural Bridge station in North City}

MetroLink expansion is not a gamble. Light rail works in communities across the country. It stabilizes and increases adjacent property values, it gets people to work and school, it shortens commutes and lowers transportation costs. Light rail focuses development in existing communities where other infrastructure, both physical and social, already exists.

A good transit system provides people with an essential transportation option. A great system moves people to prefer transit over driving. We don’t have a great system, but Northside/Southside MetroLink is the right investment, and building it will be a quantum leap forward towards a quality network, connecting tens of thousands of new people to where they want to go each day.

{mapping area around a possible Kingshighway station in North City}

{mapping area around a possible Kingshighway station in North City}

There’s a persistent myth that St. Louis area residents don’t want more MetroLink. System expansion has been stalled not by opposition, but by lack of a regional political consensus and cost overruns during Blue Line construction. But our political leadership should be less timid about expansion. Residents in the region have voted multiple times in the last 20 years to increase the local sales tax to fund the Metro system. St. Louis County voters approved the Proposition A sales tax with 60% voting yes in 2010. Surveys of the region consistently show residents rate transit expansion highly.

Last year I heard a rather prominent local radio personality puzzle, “Trains seem to work better in Chicago than they do here.” No kidding. Why? The Chicago region has 385 stations between its two passenger rail systems, compared with 37 stations in St. Louis. While the Chicago region has 3.5 times the population of the St. Louis region, it has 11 times the number of rail stations, and 10 times as many light and heavy-rail transit routes. What Chicago has is the network effect. More lines reach more of the region. There are more convenient places to board the system. There are more connections between transit lines. Transit does work better in Chicago, but it’s not magic. They simply have more transit access and options per person than we do in St. Louis.

The Northside/Southside MetroLink line would be a leap forward for our system, transforming it from an east-west alignment to a network that reaches many more people where they live. The new route would connect primarily residential and local commercial corridors in north and south St. Louis to major employment areas in the region like Downtown, the Central West End / BJC, Clayton, UMSL, Lambert airport, and Scott Air Force base.

What would a Northside/Southside system look like? It’s a street-running system. You can call it a modern streetcar or light-rail, but it’s not a trolley. It’s an electric system with overhead power that runs in its own right of way, primarily in the middle of the street, with signal prioritization at intersections. Stations are located at primary intersections like Jefferson and Arsenal, and are accessed by crossing at the crosswalk.

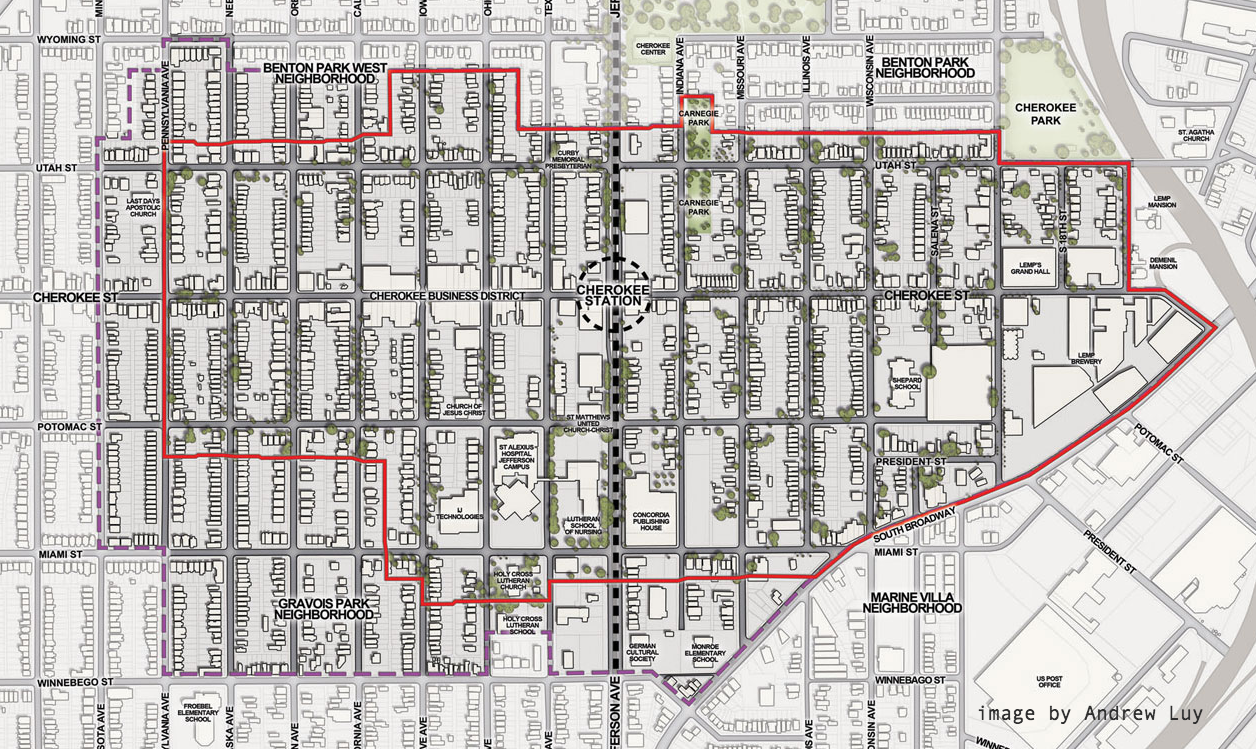

{mapping area around a possible Cherokee Station in South City}

{mapping area around a possible Cherokee Station in South City}

A just built, apples to apples comparison is the Green Line which opened in Minneapolis and St. Paul in the summer of 2014. Within 4 months of opening, the line was meeting ridership projected for 15 years into the future. Close to 40,000 people per day are already riding the Green Line – fully 2/3rds of MetroLink system ridership over only 11 miles of track. The Northside/Southside line is comparable in a number of ways – a street running system which intersects with an existing transit line and connects residential areas to downtown. We can expect it will be similarly successful if built.

{the Green Line in Minneapolis opened this summer – image by Michael Hicks on Flickr}

{the Green Line in Minneapolis opened this summer – image by Michael Hicks on Flickr}

Both north and south St. Louis were built around an extensive streetcar network, and the dense building stock and fine grained pedestrian environment are largely still intact and ready for transit to return. It’s easy to see the capacity for re-investment all along the corridor: at Cherokee and Jefferson, at Grand and Natural Bridge, and most pressing recently, along West Florissant in Ferguson.

How do we pay for it? Because of different state and federal funding formulas, light-rail is unfortunately more difficult to pay for than highway expansion. Despite a price tag likely north of a billion dollars even for a partial build, with political focus there’s a path to paying for the project. Northside/Southside is the only route within the region likely to receive federal funding. St. Louis County has unencumbered revenue from existing Metro sales tax which is not being spent. St. Louis City is authorized by the state to raise the sales tax for the Metro system by an additional .25%.

A substantial portion of the Northside/Southside route travels on MoDOT controlled roads, allowing MoDOT to contribute funding for certain infrastructure components. And let’s not write off the state. While Missouri has been MIA on transit funding for years, other red-leaning states have evolved past looking at public transit funding as a partisan issue. A few have recognized that it’s nothing less than the difference between survival and irrelevance for aging urban areas.

We’ve been here before – there were steeper hills to climb before the first MetroLink line was built. But 20 years from today, we’ll look at the Northside/Southside route as the most essential part of the system. It will be difficult to imagine St. Louis without it. Lets get started.