As Missouri considers its transportation future and how to fund it, we’re reposting the series “A World Class Transportation System” by Chuck Marohn, president of the organization Strong Towns. Its mission is “to support a model for growth that allows America’s towns to become financially strong and resilient.” They cover a broad range of topics beyond transportation, check them out. This series focuses on the transportation conversation in Minnesota, but is analogous to ours in Missouri. The two states are close in population and land area and rank fifth and sixth in total lane miles of highways, roads, and streets. We’re also working to bring Chuck to St. Louis this fall. If that’s something you’d like to help with please contact Richard Bose at [email protected].

The Move MN proposal to expand the transportation slush fund with the least painful, and most indirect, revenue source their coalition can agree on is missing any acknowledgement of why we are so critically short of transportation funding in the first place. That lack of acknowledgement likely stems from a lack of understanding, especially poignant since expansion of the transportation slush fund will only undermine the long term viability of Minnesota’s transportation system.

In short, more slush fund revenue is the problem, not the solution. To understand this, we need to examine the financing of America’s first great transcontinental transportation investment: the railroads.

The construction of America’s system of railroads is a complex and nuanced story full of crimes against Native Americans, the exploitation of Asian labor and the general pillaging of the countryside. I’m not trying to gloss over these aspects (I know someone is going to be upset with me for doing so regardless) but I do want to focus on the financing of this system, which would have been the same whether or not our ancestors had behaved in an enlightened manner.

The government’s initial role in the creation of the railroad system was to expropriate the land from its inhabitants (with little or no compensation) and then give it to the railroads. This government “contribution” to the effort was enormously important and the network of railroads likely could not have been built without it. There was, however, no real financial “cost” to this gift since the government owned much of the land anyway (and again, I’m not endorsing the “might-makes-right” approach that brought about this situation).

Once they had the land, private railroad companies then built the railroad lines. They paid the enormous capital costs by issuing bonds – borrowing the money – and then paid back those loans through a value capture mechanism. When the railroad stopped somewhere, that somewhere became a town, and the land in the vicinity of that stop became vastly more valuable. The railroad companies owned, or acquired, the land at each stop before it was built. Thus, by selling that land once the railroad line was constructed, the railroad company captured the increase in value their investment had created.

So in addition to operating the railroads, these private companies were also land developers. Without developing the land and capturing the value their investment created, few railroad lines would have ever been built.

Once the railroad was built and the capital costs recouped through sale of the appreciated land, then the private railroad company could switch to operating the line. They charged fares to move freight and people along the railroads they had built. While some borrowing costs were retired through the fare box, most of the money collected went to covering operations, maintenance and profit.

It should be pointed out here how great an investment the railroad now was. So long as the company didn’t overload the trains, the nearly frictionless tracks would stay in place indefinitely, requiring only a modest amount of maintenance. There are stories of tracks lasting over a hundred years, with replacement only coming when the company wanted to increase the weight the line could serve. That means that maintenance costs could be spread out over a very long period of time.

This system sounds great, but it didn’t always work perfectly. There were many occasions when the private railroad companies made bad investments, when they built towns and not enough people showed up to buy the land. In fact, after the U.S. Civil War, foreign money poured into the country and fueled rampant speculation in railroad-led development. When these investments got too far out in front of the market we experienced the Long Depression of the 1870’s, a very painful financial correction that forced a lot of railroads out of business. It was the speculative housing bubble of its day.

When we began to build the interstate system, in many ways we were attempting to re-create the transformative economic expansion brought about by the construction of the railroads. Only this time it would not be the private sector leading the way and taking the risk. It would be the government.

This was consistent with our evolving sensibilities on the role of government. Not only had Americans of that time lived through the Great Depression, they had also seen the awesome power and efficiency of centralization on display in America’s efforts in World War II. We can accomplish great things when we collectively focus on something of national import. FDR, Truman and then Eisenhower were great leaders that embodied this ethos.

(Note: I’m not trying to start a debate on whether or not New Deal policies were good or bad, whether the centralized, Keynesian direction our economy took at this time was necessary or not. My grandfather, a World War II veteran whose formative years were in the Great Depression, once told me that, “Without FDR, we would all be dead.” He climbed the cliffs in Nagasaki Bay after the bomb was dropped then returned to work in a paper mill for the next four decades. I’m not going to question his assessment of economic conditions in the 1930’s.)

We chose to fund this expensive national undertaking with a communal tax on gasoline. There was some logic to this; the people who bought gasoline would be using the roadways and would thus be paying for what they used. The collection costs of a more direct user charge was not really feasible at the time.

With a government-led system, politicians would decide what got built, when and where. This wasn’t a problem in the early years when there was a lot of money for building roads and very little local match was required. It was especially easy for local officials to embrace the system because highway investments created a lot of wealth locally with very little direct cost to the local taxpayer. A new highway through a cornfield would essentially print money for locals, creating enormous wealth for a class of citizen that, a decade earlier, would have been struggling to make a living growing crops.

It also dramatically improved the cash flow of local governments in the process. Maintenance costs were high – those bituminous roadways require continuous maintenance or they fall apart rather quickly – but oil (and thus asphalt concrete) was cheap, as were transportation costs. The really high maintenance expenses were a generation or more away.

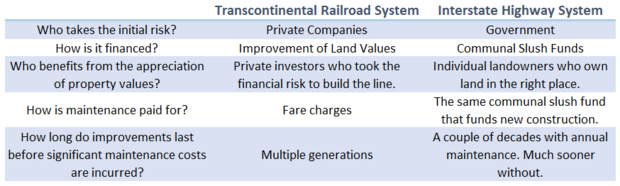

Let’s pause here to contrast these two systems.

To summarize, the transcontinental railroad system connected the entire country with a transportation network that was privately built and maintained. Its expansion was directly correlated to the real financial value it created while the long term maintenance costs, paid by the users of the system, were so low they could be recovered over multiple generations. This was such a financially stable system that, as it was set up, it could have operated for centuries had technology – and government intervention – not changed the marketplace for transportation.

We replaced this stable system with the interstate highway system and all of its related state and local auto-based improvements. The expansion of this new system was not correlated with the value created, or with real demand, but with the priorities of the political system. Since expansion bestowed windfall gains on those positioned to benefit from expansion (individual landowners at first and, ultimately, major national/international corporations), as well as local governments who experienced quick and easy growth (with the costs put off a generation), there was plenty of “demand” generated within the political system for doing more. Maintenance was not funded by user fees but by a slush fund (the gas tax) that, over time, has been augmented with general taxation.

There are two travesties embodied in our current situation. The first is that our current approach to funding transportation has no correlation between supply and demand. We all subtly pay into a giant slush fund and then we all expect that slush fund to deliver on its promise to meet our insatiable demand for growth. Members of the engineering profession have called taxpayers “whiners” for not wanting to pay more, but why would anyone pay more for something they don’t really value?

Now I acknowledge that people do value transportation, but at what price? Nobody really knows. Time and again we see that, when prices are not hidden in a slush fund but instead are paid by the user at the time of consumption, demand drops. For a government-led transportation system, a drop in demand is devastating. Put a toll on that road priced for current usage and fewer people will use it. The drop in demand forces an increase in the toll if the same revenue is to be sustained. An increase in the toll further depresses demand and on and on and on…

This fear of collapse in real demand prevents us from taking actions that would more closely reflect the costs for users. It is as if the owner of a hot dog stand loses a dollar on each dog they sell but refuses to raise prices to cover their costs out of fear that they will lose customers. In the private sector that busines would quickly fail. In a government-led system, something very different happens.

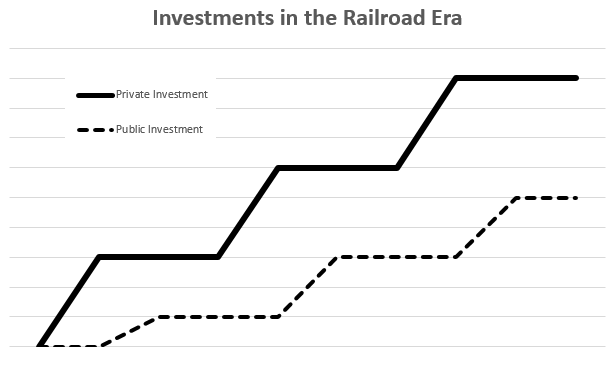

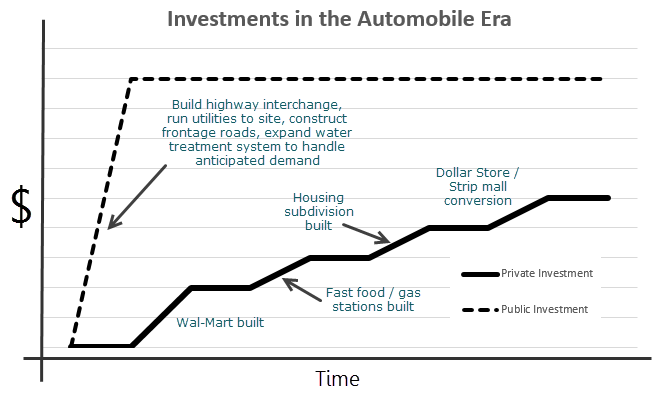

That brings us to the second travesty, the interaction between public investment and private investment. In the railroad era, private investment always led public investment. The railroads would construct the lines, build the towns and the town itself would be somewhat established before any public investments were made. In other words, the private sector bore the risk that the development would not work out. In a rough sense, this is how public and private investment would interrelate.

In the automobile era, the risk taking is reversed. For all but the most local of transportation improvements, governments front the investment capital and take the risk. This is so accepted that it is never really questioned. The interrelation between public and private investment in the automobile era is quite different.

Here’s where the perversity kicks into high gear. What happened when the private railroad companies overbuilt their system? What happened when they got out in front of market and had too much supply without enough demand? They, of course, got the painful feedback of losing money and watching their assets drop in value. Sometimes entire companies went out of business.

What happens when the government, operating in the automobile era, overbuilds? What happens when we create so much supply, so many miles of roadway, that demand can’t possibly utilize it effectively? Well, the feedback isn’t quite so direct. Budgets start to be frayed. Obligations go unfulfilled. Stuff start to decay. There isn’t enough return on these government investments and so there ultimately isn’t enough money to care for them. We often attribute these symptoms to others causes — spoiled taxpayers, the 99%, the 1%, “those” people, lazy government, greedy corporations — most of which appeal to our psyche more than the idea that we’ve overbuilt (no retreat).

In fact, with public sector investment now leading private sector investment, we can actually forestall the painful feedback (recession/depression) by – wait for it – making more government investments. Yes, our core transportation funding problem is that we’ve built more transportation infrastructure than we are effectively utilizing. Our solution, bizarrely, is to build more.

So long as the government has the money to avoid the hardest decisions, any uncomfortable response – land use changes, shifting from automobile trips to walking or biking or modifications to the tax code, to name just three – will remain off the table, or at least relegated to the fringe. More money doesn’t solve our problems. It just forestalls the pain of transition, compounding the imbalances in the process.

One last observation on the current approach: it has long astonished me that we culturally abhor the concept of value capture. When my hometown was bypassed, Mn/DOT made millionaires out of a number of people who had done nothing but have the good fortune to inherit land at key spots along the chosen corridor. Did we, in our desperate lack of funds, ask for even a tiny portion of that wealth back to pay for the improvements that created their good fortune? Of course not, yet when we rerouted the highway we insisted on compensation for the gas stations and other auto-dependent businesses — located on sites previously owned by last generation’s transportation lottery winners — that would now see their traffic counts decline, as if the state’s role is to guarantee a base amount of congestion.

Without a correlation between supply and demand, without any painful feedback for bad investments and underutilized infrastructure, more money will only make our problems worse. I’m sympathetic to those of you who – as one reader emailed me – “just want a train”, or those of you that want to continue to live your current lifestyle at current prices. I’m sympathetic, but my sympathy won’t make the math work.