The notion of this series as “experiential journalism” was labelled prominently in the pitches of this series to possible crowd-funders, then readers. The idea was that I’d not only be covering the story as a journalist, but as a person allowed access into a scene; whatever happened from then on, I was open to witnessing and taking part in. As someone who’s covered various subcultures over the years, I assumed that tapping into the underground world of graffiti writers would largely take pluck and time.

My working theory was that those who do graffiti are usually lumped into a public enemy category, whether they’re gang tagging, or putting up elaborate, artistic pieces, or expressing displeasure with the system, in whatever form. My further assumption was that some folks would want to explain their rationales or motivations, especially if others in the scene were taking part in the conversation first. Once a domino fell, others would follow and some sense of communication could begin to take place. As it is, graffiti’s largely a one-sided monologue. A bit of script or a drawing goes up on a wall, it’s reacted to; whether by disgusted head-shaking, the spray of paint remover or the occasional pronouncement of “right on.”

It’s a war for what we consider appropriate in the common space.

And here’s where things get tricky and sticky.

On a certain level, I’m a tinfoil hat kinda guy. I believe that we’re as a culture, opening ourselves up to the type of surveillance that would’ve been unthinkable before some airplanes struck major American landmarks a decade-and-change ago. My belief is fueled by walks across the college campus I work at, where cameras sit unobtrusively in hallways and on the tops of buildings. I notice it when walking or cycling through the city, slowed down from the quickened pace of a car; in those moments, you notice those cameras again, tucked into window-wells or attached to power lines.

Usually, they’re there for a reason, somebody assuming that there’s a need to watch this little corner of the world. On the South Side, that might mean a parking lot that’s been targeted for break-ins, or an alley that’s been known as a good spot to dump tires or construction waste. In a sense, I’m cool with the idea that brick rustlers or petty thieves are being given a moment’s worry, maybe even providing evidence on their own activities. But the open eye of a camera doesn’t choose; it captures everything and therein lies my sense of disquiet: I’m fine with the idea that I’m not doing anything wrong, and, therefore, cameras shouldn’t bother me. But they do. Pretty much always.

And from that paranoia, I can make a jump to the idea that graffiti writers have some sort of Robin Hood quality, even if they don’t believe that, themselves. To me, there’s some value in the shock troops, the folks who live on the razor’s edge of legality. They provide a notion of what’s possible, acting out life on that edge. When I see that a tagger’s spent real time hanging over moving traffic on a bridge or train trestle, I thrill to the idea of the adrenalin rush they were feeling at that moment. And if the work’s of high-quality, that idea’s multiplied, as it’s one thing to get up, it’s another to execute a rad piece.

Of course, a lot of the act is just done for the sake of the act. I know that now, I really do; this has been beaten into my head in various forms over the past three months. And here is where I find myself departing from being a fanboy. There are acts done that strike me as aggressively anti-social, done for the simple sake of messing with someone’s head or commerce or manhood. Is it time for a vignette?

(photo: anything interesting from my flickr, or the anarchist snail, sent to you)

Vignette #1: Houses of the Holy

When we began our conversations, nine weeks ago, the first piece centered on Powell Square, a building that was demolished earlier this year. There were last-second attempts to buy the building some extra time, with activists suggesting, in one model, that the building could be transformed into a new form of vertical, urban farm. Those efforts fell short of the mark. After which, the building, itself, fell. At the time, much of the conversation around the issue had to do with the idea that the Powell was a magnet for tagging, a near-museum of pieces. And, importantly and negatively to some, it was the last thing that folks saw on their drive out of town.

While some tears were shed, others applauded the action, suggesting that the building’s departure from the downtown skyline was a positive. The building was erased and, in the process, so were the scars that people saw in the form of spray painted markings.

My guess in that first piece was that the area would still be a canvas, with other, nearby spaces taking the place of the Powell. True enough, buildings nearby have been tagged plenty, some of them abandoned, some still in use. Recently, the church that long neighbored the Powell Square, St. Mary of Victories, a Hungarian parish, was targeted. LD crew members Durag and Bang, two of the most-prolific and bold graf writers in town, covered the north-facing wall of the church grounds. That wall, itself, isn’t necessarily special, though it has some neat, circular cut-outs on the western side.

But no matter how you slice it, these writings are, in essence, on the property of a church.

This matters? This doesn’t matter?

Couldn’t be more agnostic in life, but, to me, when you tag a church, it feels like it matters.

(photo: nextgraf_church, sent to you)

With a Little Help From Friends

Spraypainting in public settings is fun. Won’t lie about this.

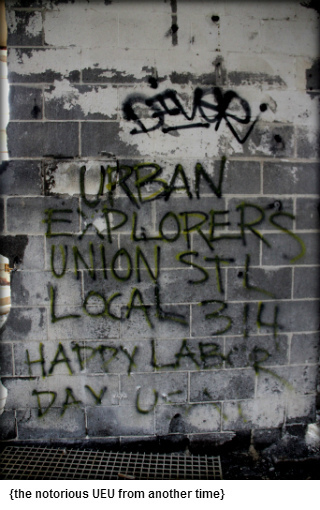

A half-decade ago, I ran around with a group of friends, between a half-dozen and dozen in number. As if we were kids establishing some of type of playground gang, we dubbed ourselves the UEU 314, or Urban Exploration Unit (or, alternately, Union) 314. It was all in good fun this name, just a way to self-affiliate. Over some years, we visited dozens of abandoned buildings, rail lines, public walkways, and other spaces that were seemingly off-limits to the average citizen. To us, those outings were a nice, every-few-Saturdays staple.

Eventually, we dwindled apart, folks finding other people to run with, or, more generally, other things to do with their time. The UEU conceit kinda drifted away.

But in a handful of spaces around town, there’re marks up. The UEU was there and was active. We came, we saw, we spraypainted. We left a “howdy” through a simple act, and it was fun to do. On Flickr, a few shots suggest as much, though I don’t recall who actually write the message in the accompanying photo; I have my guesses, though.

Have I done graffiti? In a very narrow sense, yes.

Am I a “toy”, a dilettante. Yes, no doubt. More on that in a minute.

Vignette #2: The Battleground

It’s been suggested here before that the region’s busiest, most-public, street-level showcase for graffiti lies along Cherokee Street, where empty storefronts, trash cans, stop signs and every other bit of free space seems complete with a tag these days.

The mix displays pretty much everything that can be regarded as graffiti or street art, from stickers to quickly-sketched names to anti-police posters. The range spills off the street and into neighboring ones, the state streets that shoot off in north-south lines from Cherokee. While the western side of Jefferson typically would be regarded as the place with the most graf, it’s not limited by the geography of this single street.

Recently, while leaving a coffeehouse on Cherokee’s eastside, I noticed the back of a nearby stop sign. In the mix of items attached to it came a simple message. “Duh!” it read. Nothing more, nothing less to that one, just a phrase and an exclamation mark, slapped up there with some of drip-ink marker. I was in need of a laugh at the moment I saw it, my head swimming upstream against the day’s worries. Somehow, this random note gave me a smile and something else to think about, something other than deadlines and mopery.

This anonymous act was appreciated. If illegal. Thanks, pal.

Gettin’ On Up

There’s a long-running history of athletes releasing records. They’re usually awful, but there’s no mechanism in place to keep them from doing so. Less frequent, but also there, is the trend of musicians or artists wanting to be athletes. It’s not a long list, but a few have tried, mostly to no good end.

If there was a predictable thing that this series would lead to, it was my finding my old markers, long since retired. After touching up the backs of a few South City dumpsters, maybe adding a bit of brightness to the inside of a bathroom, or two, I’d assumed that I’d aged out of the whole activity.

That dilettante thing and all.

Yesterday, I was pondering this series, my emotions wildly swinging back-and-forth. At moments, I figured that everyone involved in graffiti was an asshole, somebody with a needless desire to register their existence through the placement of a name on a wall. At other times, I wondered if I’d taken the wrong approach to all of this, that if I’d distributed word with more respect, that the feedback would’ve come, that I’d have somehow reached the folks that want to change the world through small bits of sloganeering agitprop, registering their existence through the placement of a message on a wall.

Who knows? Not me. Not after 10 weeks, at least.

I can, say, though, that my notions of feeling trapped by society’s constraints are there, were there. I had my instrument at the ready yesterday, a Broad Line DecoColor Opaque Paint Marker. It fits in a pocket. And to get it ready to write, you’ve gotta do this little shakey-shakey thing, which sends the ink up to the right side of the marker. There’s a little bit of process, of prep that way. It’s fun to hear that audible shakey-shakey of the marker in the seconds before something goes down.

Lost in the county, the victim of too many highways and too much caffeine, I settled in to relax at a corporate coffeehouse. I studied the scene, which was mostly geared to service the location’s drive-through. Inside, a couple people noodled on their laptops, while two, in-uniform soldiers lounged in a corner, their heads reclining against the wall. After a half-hour of light work on my laptop, I walked into the bathroom; guys can dig the specifics. There were no walls inside, just a toilet and a urinal and a sink and some light. I thought about tagging the room with a message of peace, but wondered if even the bathrooms at the local, corporate coffeehouse were jammed. I was guessing, guessing, guessing, questioning and then, bang, I decided to bail.

Getting closer to home, to the South Side, my worries began to subside. Another of my many working theories about graffiti is that you could track most of the action in town to the bars at which graf writers drink, or work. If you studied the patterns, my guess is that graffiti could be diagrammed neatly, with tracers fanning out from South City bars, the paint not stopping until the graf writer’s front door. I thought about this as I pulled into a familiar haunt on the South Side, taking an extra minute to walk the perimeter of the area. As I did so, I cut through an alley. Though open to passing traffic, the shakey-shakey of my marker started and a one more local dumpster took on a message.

My annoyance of being lost earlier in the day, my worries about needing hours to write and grade paused. I felt elated and a bit naughty, a schoolboy who got away with it.

Dilettante, or no, it’s there. For how long? Doesn’t really matter. No one got hurt. No one’s the wiser.

Vignette #3: A Street Runs Through It

There’s a utility box in the dead center of the Webster University campus. It’s long been stickered by the letters QAEK. This is the handiwork, any logical person would conclude of the LD writer Qaek, aka Quekr. He works with spray paint, pre-made logo stickers and these single-letter stickers, too. He’s got a wide base of operations in the City and beyond.

But the placement of this one’s unique.

Webster University is a clean campus. This is proven to me every time I visit a larger one, where there’s a bit of a chaos in the public space. Those big silos that you see on a major campus’ quad, there for students and promoters to slap up concert posters and yard sale flyers? On a campus like Webster, they’re non-existent, with some of the interior spaces moderated; guerrilla flyers, if not approved by the campus authorities, get yanked without the proper stamp. It’s not weird, I guess, just different.

So to see this QAEK on the utility box, in place for months…. well, it makes me laugh, makes me smile and makes me think there’s something still a bit useful in all this, as people communicate to one another through marks and meanings that not everyone’s hipped to. There’s a world of subliminal conversation taking place, if you’re open to it. Some of it’s crass, rude, inappropriate. Some (okay, less) has a quality of quiet intent, allowing you to break away from the daily grind, the recipient of a person-to-person message.

Tagging a church? The high-profile brick wall of a privately-owned home? The empty remains of a packing plant? There’s intent in each. I can’t explain what that writer might’ve been thinking. Probably, I shouldn’t have assumed that I could when this process began. Live and learn, I guess, and never stop asking around. That’s what I’ll take away from this. To the degree you did, thanks for joining me.

For Further Reading and Viewing

I was tipped to a great article on this topic, circa Cleveland, where a blog called coolcleveland.com details the graffiti and mural of Collinwood, which I’m told, is “the Cherokee of Cleveland.” Totally worth a read.

Have you long thought of getting up, with your own version of the ET? If so, YouTube can show you how to get it done:

Essential reading, William “Upski” Wimsatt’s “Bomb the Surburbs”. ‘Nuf said.

This series is done. But not before a hail mary. RatFag, let’s talk. I’m invested:

Maybe share a pint or Thanksgiving dinner. We’ll do this?