Recently I read a newspaper article about a major urban development project that included these two sentences: “He received hundreds of millions of dollars in public cash and incentives. But after a long public review process, the developer was buffeted by a recession, community opposition and a weak market.”

Recently I read a newspaper article about a major urban development project that included these two sentences: “He received hundreds of millions of dollars in public cash and incentives. But after a long public review process, the developer was buffeted by a recession, community opposition and a weak market.”

Here “he” is Bruce Ratner, the project is that foam-finger to Brooklyn called Atlantic Yards, and the article appeared in the New York Times on August 21. St. Louis reporters got the chance this week to avoid plagiarizing that depiction, because it could have applied to coverage of Paul J. McKee Jr.’s NorthSide Regeneration project in wake of its hearing at the Tax Increment Financing Commission on August 28. (The Commission will vote on whether to recommend a $390 million TIF to the Board of Aldermen at a separate meeting on September 11.) The parallels are dramatically similar despite very different physical settings: these two projects took aim at vacant public land, were subsidized by state governments after local governments started scrutinizing them, have involved ridiculous amounts of campaign contributions to both Republicans and Democrats, have been pitched as solutions to urban unemployment and have withered in implementation as the economy has changed.

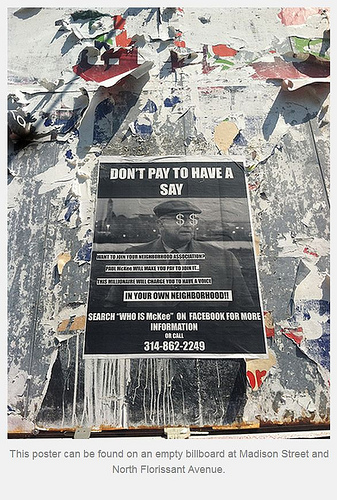

In New York, Ratner is selling as much as 80% of Atlantic Yards. That outcome should catch attention here, because those locals who think that NorthSide Regeneration will always have one face – one target for activist scorn – should be ready for the dozens of developers who will end up eventually working in the project area. While McKee’s name has a tarnish that brings scrutiny to every action of his company, the new names may not – and may have a lot more to do with actual decisions about condemnation of private property. Mayor Francis Slay, Alderwoman Tammika Hubbard and other cheerleaders for the project will not be around either, rendering their promises of the good life for north siders fairly innocuous at best, blind at worst.

As we deliberate on “activating” tax increment financing for NorthSide Regeneration, familiar repetitious cycles emerge. McKee on Wednesday presented a rather amorphous PowerPoint show whose oldest slides are now five years old, and reiterated even older claims about the jobs he could create and the $8 billion in “development” (unspecified as to specific activity) that the project would complete. The exact completion date has pushed forward, but the timeline and promises seem very much like those advanced in 2009.

The project itself remains very much the urban renewal behemoth McKee admits to hatching over a decade ago – when lending was liberal and palpable small-scale development on the near north side was less obvious to the untrained eye. McKee has been quick with excuses for his project’s lethargic pace. First there was the need for a state tax credit, then tax increment financing, then overcoming Judge Dierker’s ruling, then waiting for the pending Supreme Court decision, then extending the state tax credit (which did not happen), and now the need for a tax increment financing ordinance again. What shall be next?

As usual, McKee’s company posits NorthSide Regeneration as a social reform mission that will transform lives as much as land. McKee’s wife Midge McKee spoke on the Demetrious Johnson radio show recently about how she had a dream about the project, and how it would serve residents. Her dream was replete with churches, a sign that existing residents were staying and thriving.

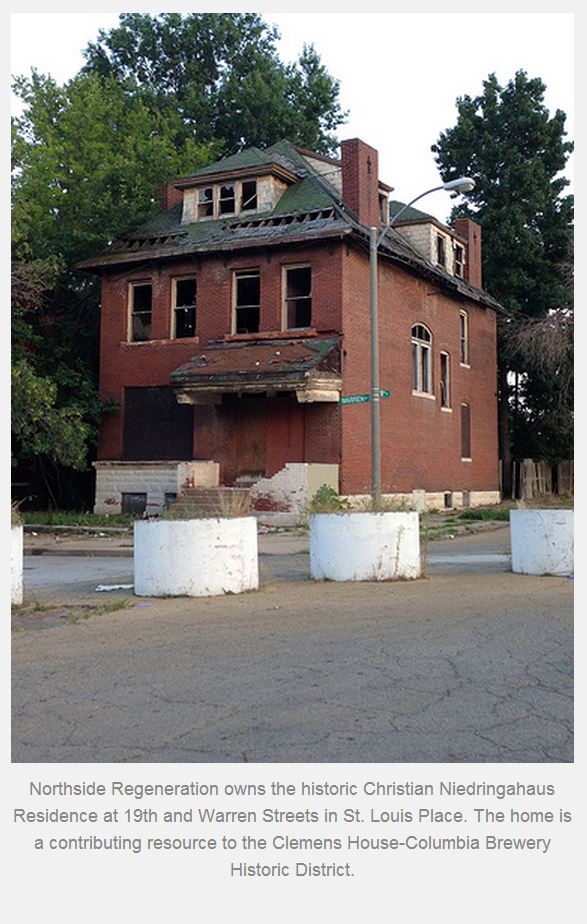

That dream should not be dismissed, but it runs counter to the entire program of the development and its current operational practice. Clearly, for the last decade the McKee’s dream has cost the near north side hundreds of residents who have moved out of houses and apartments sold to their shell holding companies. Who knows how many people fled as they saw the NorthSide Regeneration properties torched, brick rustled and otherwise left to rot. Blockbusting need not be intentional, after all. Myself and others have counted how many irreplaceable architectural treasures have been lost to the scheme.

That dream should not be dismissed, but it runs counter to the entire program of the development and its current operational practice. Clearly, for the last decade the McKee’s dream has cost the near north side hundreds of residents who have moved out of houses and apartments sold to their shell holding companies. Who knows how many people fled as they saw the NorthSide Regeneration properties torched, brick rustled and otherwise left to rot. Blockbusting need not be intentional, after all. Myself and others have counted how many irreplaceable architectural treasures have been lost to the scheme.

Still, the McKees espouse very sincere intentions about uplifting the north side. Unfortunately they have chosen to do so through real estate development, mass demolition and land assemblage. These tools have only been used to disintegrate the near north side, and not for one day have they ever created permanent jobs for poor African-Americans, or stabilized a community of humans, or benefited anyone except government agencies and politicians, real estate developers, construction companies and trade unions, and others who either realized profits or power from destroying historic neighborhoods. Today, the profits and power look anemic in comparison; NorthSide Regeneration’s first retail “deal” may be a Dollar General store. If the developers are reeling in such small fish to stay afloat, what will residents get to catch?

Little discussion of NorthSide Regeneration has examined the similarity of its program and boundary to the city’s north side Model Cities zone. Created by the Johnson administration, the federal Model Cities program provided funds for urban “reconstruction” of older neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty. In St. Louis, the city’s Model Cities Agency designated a wide swath of the inner city for the program in 1966, and maintained activities there until the program’s dissolution after 1974. The north side area included Old North, St. Louis Place and JeffVanderLou – almost identically to McKee’s original footprint (Old North is largely carved out now).

Model Cities was supposed to regenerate the near north side. The program gave city officials funds for demolishing nearly 1,100 housing units in St. Louis Place, converting the 14th Street shopping district in Old North into a pedestrian mall, and building new housing. In the end, the “too big to fail” approach led to embarrassingly haphazard implementation of the city’s programmatic master plan.

Most of what Model Cities achieved was housing demolition, with funding for new construction delayed or non-existent. Clearance depleted vitality and disrupted social life, causing a downward spiral. When McKee shows slides of conditions in the area, he never mentions that the federally-funded version of his project helped create them — and that its aims were very similar.

Supporters of NorthSide Regeneration’s aims are fast to join in the chorus proclaiming “McKee did not create the blight he is trying to fix.” Despite some truth to the contrary with conditions of his company’s properties, that chorus sings a true tune. Yet the song bends the ear with the refrain “other large scale projects did this.” Model Cities followed the city’s implementation of the 1947 Comprehensive Plan, drafted under the direction of Harland Bartholomew. That plan infamously included a map with a black zone showing “obsolete” housing — the oldest neighborhoods, which were also the poorest.

Bartholomew’s concentric zone approach led to the city’s using the bulk of its federal funds from the 1949 Housing Act to demolish swaths of the near north and near south sides, while trying to take on more. Today’s urbanists are proud that they dwell in places like Old North and Lafayette Square, both inked black in the 1947 plan. Yet they might not see how the plan’s implementation is ongoing on the north side.

The near north’s most frightening large-scale redevelopment project was the combined Pruitt and Igoe housing projects, completed between 1954 and 1956. The Pruitt Igoe-Myth renewed a generation’s awareness of not only the projects’ histories but the social and political context in which it happened. That film makes painfully clear that architecture – essentially development of land – cannot solve social problems, no matter what its design intent, how high its construction cost, how great its architect or how blind its political supports are to what they are doing.

Pruitt-Igoe, unlike NorthSide Regeneration, was built by an accountable federal government and managed by an accountable local government. Pruitt-Igoe was built to house poor people — directly serving them. The project failed to do anything completely save clear 25 blocks of African-American residents and businesses, and scatter them across the region.

Today, NorthSide Regeneration is not dealing with the same density. There are no 25-block areas housing over ten thousand people within the project footprint. In fact, St. Louis Place has a mere 2,900 residents. Total. The dispersal of people reached its peak, and the population is very small. Yet the near north side is showing population growth for the first time in sixty years, according to the 2010 Census. Since NorthSide Regeneration has yet to develop any housing, we know it is not through that project but through other people’s hard work. Residents who remain are more likely to enjoy the area and hope for its growth than ever before. There is exactly the sort of community that Midge McKee sees, but it is more likely to be negatively altered by a giant project than not.

Today, NorthSide Regeneration is not dealing with the same density. There are no 25-block areas housing over ten thousand people within the project footprint. In fact, St. Louis Place has a mere 2,900 residents. Total. The dispersal of people reached its peak, and the population is very small. Yet the near north side is showing population growth for the first time in sixty years, according to the 2010 Census. Since NorthSide Regeneration has yet to develop any housing, we know it is not through that project but through other people’s hard work. Residents who remain are more likely to enjoy the area and hope for its growth than ever before. There is exactly the sort of community that Midge McKee sees, but it is more likely to be negatively altered by a giant project than not.

As the TIF Commission stares at the same giant project, unchanged, and as the Board of Aldermen looks at needed legislation this fall, perhaps some member of one of these bodies will examine NorthSide Regeneration against historic precedent, against its invented promises (jobs, $8 billion) and against the needs of the people who inhabit the soil the project aims to reorder. Any one of those factors renders the current project a cousin to the wrong way of thinking about community and redevelopment – ways rightfully slammed, in light of another local clearance project, by Tracy Campbell in his new book The Gateway Arch: A Biography. All of us should look instead at NorthSide Regeneration’s lease of vacant lots to neighborhood urban farmers — an unheralded good deed by the company — as the sort of synthesis of microdevelopment and existing community that actually could create wealth for people in the neighborhood.

St. Louis, like many peer cities, chose to assume the stance of Sisyphus to the stone of urban renewal. Once that stone was a near-match for the public good, and now it resembles private interest. Either way, tax funds pay for its construction – and it never rests where it is supposed to (rebuilt neighborhoods, job creation, increased tax revenues, poverty alleviation, sustainable new urbanism). Intentionally or not, NorthSide Regeneration has inured itself to forces that have perpetuated failed approaches to rebuilding the city.

Chasing large-scale projects has drained the city of over a half-million people, making the 2,900 people in St. Louis Place more consequential than ever. Dollar Generals hastily built to create development cash flow are not going to change the city’s fortunes, but will follow in the footsteps of redevelopment projects that already have drained the same area of the city of historic character, residents, jobs and wealth. McKee and city officials could work on “Plan B,” or they could perpetuate the heavily-subsidized forces of urban disruption.

*this article first appeared on Micheal’s Preservation Research Office site. PRO is an historic preservation and architectural research firm based in St. Louis, Missouri.