Opening day! There are few days on the calendar that I look forward to more than this one. By far my favorite sport, I love the start of a new season. It won’t be long before I’m sitting on my porch listening to ballgames and drinking good gin.

Baseball is another reason why I love this city. Imagine re-writing baseball history without St. Louis. Imagine eliminating the Gashouse Gang, Stan Musial, Bob Gibson, and Ozzie Smith from that narrative. Eliminate the St. Louis Browns, “Cool Papa” Bell, Sportsman’s Park, Branch Rickey, eleven World Series championships, and two (maybe three) Negro National League Championships. Without St. Louis, the story of baseball suddenly becomes significantly diminished. Best of all, the fans here are passionate, they drape themselves in Cardinal red, and they fill Busch Stadium no matter where the Cardinals sit in the standings. It is a great baseball city.

Now that I’ve probably made every Cardinal fan who reading this a little warm and happy inside, I’ll make a confession that may alienate each and every one of them.

I loathe the St. Louis Cardinals.

That’s right. I am no Cardinal fan. I could barely handle it when St. Louis won those improbable championships in 2006 and 2011. I despised those Mark McGwire years when he was crushing balls off facades and breaking the Roger Maris home run record. I still roll my eyes when I see David Eckstein shirts being worn at Cardinal games. Eckstein? Seriously?

My fellow St. Louisans, before you pledge to never read anything by me ever again and hunt me down like a lippy Cub fan, please hear me out. We aren’t that much different. I love this city and the people in it. I love the buildings, the parks, the neighborhoods, and obviously, baseball. I just happen to come from a different part of the country. Born and raised in upstate New York, my baseball loyalties were firmly established long before I set foot in this city. From the moment of my entry into this world, I was bred to be an unapologetic disciple of the Evil Empire.

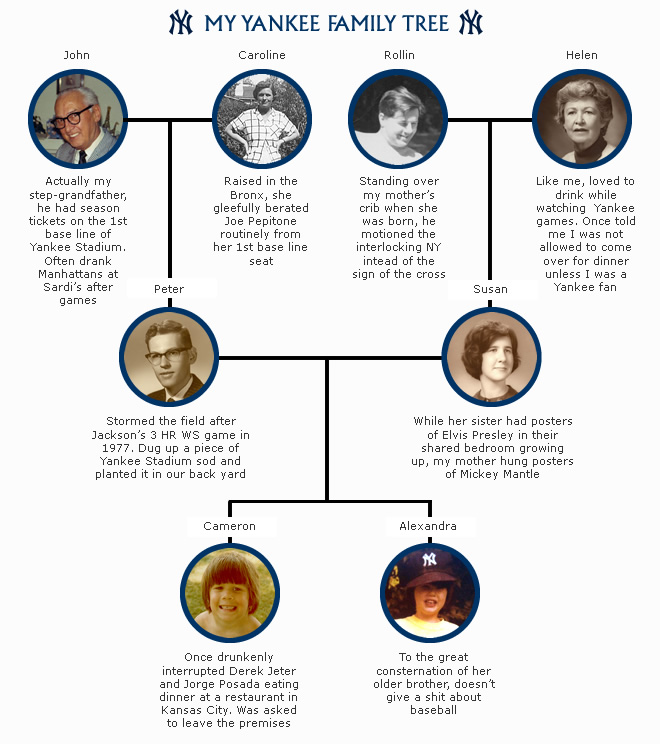

Before I get to the real purpose of this post, let me provide an infographic to detail the history of my Yankee heritage. Hopefully, it will help my St. Louis friends and neighbors understand that shifting my allegiances based on a current address (which is something I am told to do often) simply isn’t going to happen.

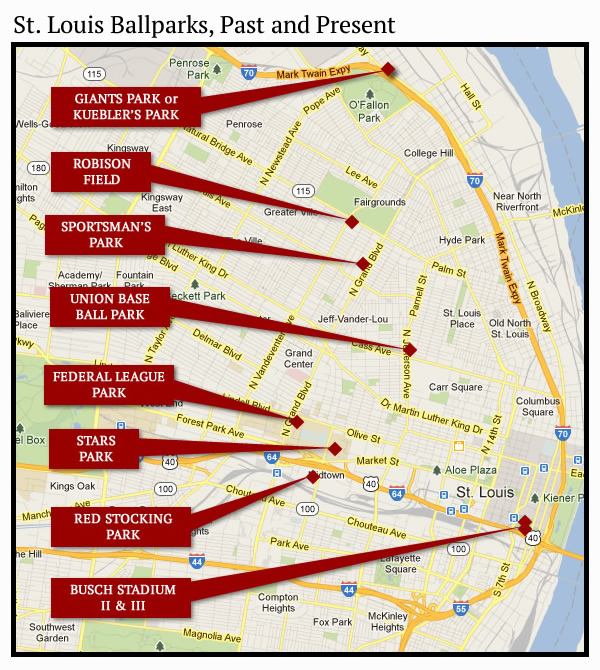

With that unpleasant business out of the way, let’s get to the real purpose of this post. With baseball being such a rich tradition in St. Louis, I wanted to find out more about where the game has been played in this city. Since I enjoy seeing where old structures used to be, I hatched a plan to find out where every pro ballpark once stood in St. Louis.

Fortunately, this turned out to be a pretty simple task. While scouring baseball books and articles, I kept stumbling upon one particular name. A St. Louis baseball historian named Joan Thomas had researched this topic in great detail already. After reading a few fascinating articles written by her, I purchased her book St. Louis’ Big League Ballparks. It told me everything I needed to know except where to find a good drink along the way.

I also discovered most of the ballpark locations in St. Louis have commemorative plaques erected where they stood. These plaques were put in place by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). Many of the ballpark histories written for SABR’s project were also written by Joan Thomas. Each plaque contains a brief history of the team, significant facts, and a diagram of the layout. Kudos to SABR, Ms. Thomas, and anyone else who had a hand in this project. I believe it’s a great way to celebrate baseball history in St. Louis.

I strongly recommend baseball fans go out and find these locations on their own. It’s fun to stand where these ballparks once stood and think about how the game of baseball was once played there.

Follow along as I visit each of the bygone ballparks of St. Louis. The parks are listed in order of their closing, starting with one that I knew absolutely nothing about.

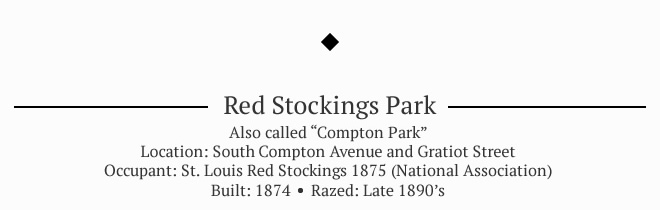

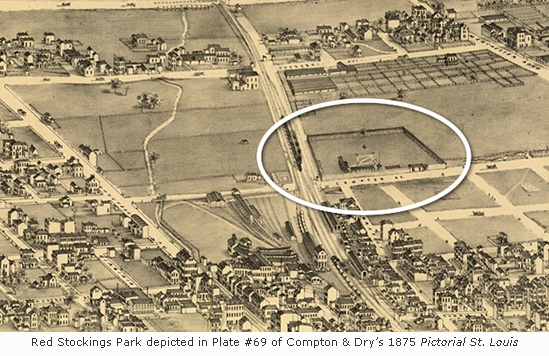

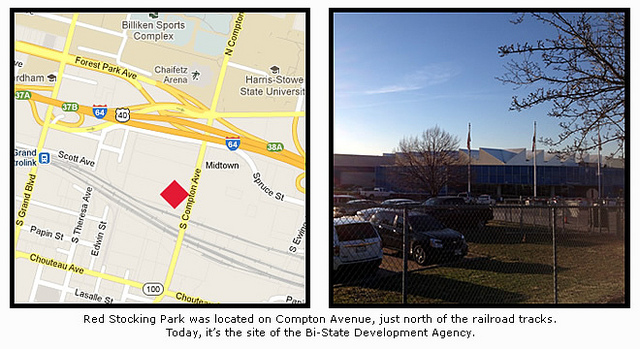

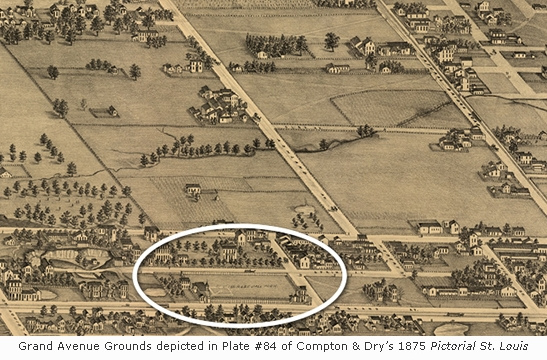

I have driven or bicycled over the Compton Avenue railroad overpass hundreds of times, perhaps thousands. Until reading an article by Joan Thomas, I had no idea that beneath that bridge once stood one of St. Louis’s earliest ballparks. In fact, it is where the first professional baseball game in St. Louis was played on May 4, 1875.

Although not recognized by Major League Baseball as a Major League, the first professional baseball league ever formed in the United States was the National Association of Professional Baseball Players. In 1875, two St. Louis clubs opted to move up from amateur status and join the league. The Brown Stockings, who played their games at the Grand Avenue Grounds, and the Red Stockings, who played in a new park on Compton Avenue just north of the railroad tracks. That park, known as “Red Stockings Park”, is where the two St. Louis teams met and played that historic first game.

Loaded with a roster of ”imported” quality players from around the country, the Brown Stockings easily beat the Reds 15-9 (the score was 15-1 until the eighth inning). This was controversial, since many believed teams should consist of local talent, such as the Red Stockings St. Louis-based roster. Success on the field settled the argument. The Red Stockings lasted just a few months before leaving the league and dropping back down to amateur status. The Brown Stockings continued to play winning baseball. They’d become a charter member of the National League the following year.

Red Stockings Park would continue to be used for amateur baseball games and other contests until it was torn down in 1898.

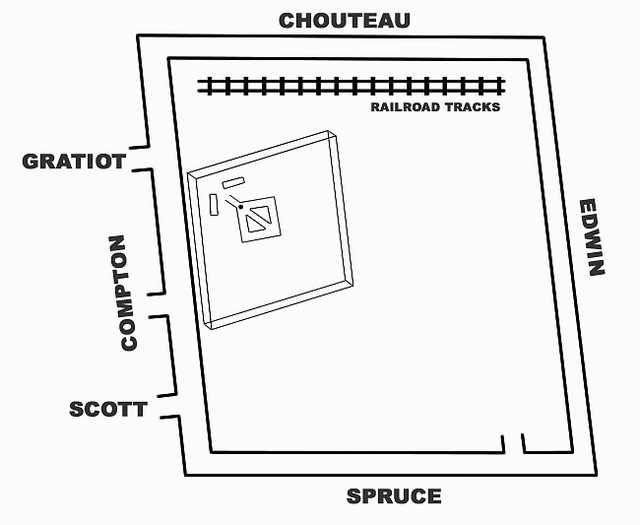

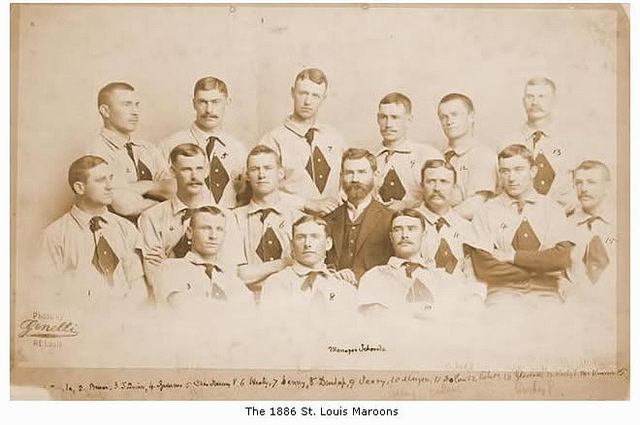

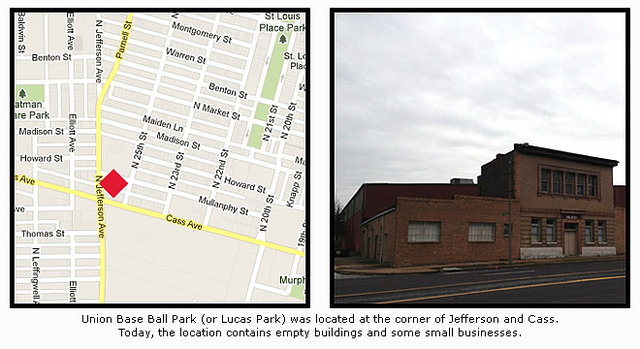

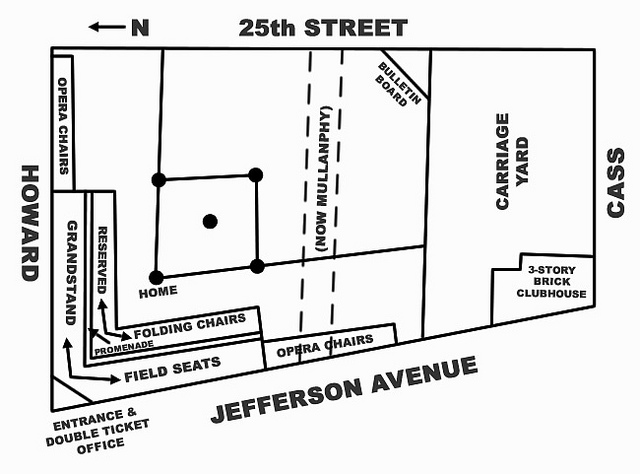

In 1883, a St. Louis millionaire named Henry Lucas decided to get in on the blossoming baseball craze. He created and funded the Union Association, a new baseball league that began play in 1884. Lucas also owned the dominant team in the league, the St. Louis Maroons. The Maroons played their home games at Union Base Ball Park, located at the northeast corner of Cass and Jefferson Avenues.

Being the owner of the league, Lucas selfishly made sure his St. Louis club was the team to beat. At the expense of other teams, he stacked the Maroons with the best talent. As a result, the St. Louis Maroons dominated, winning the title with a 94-19 record (an .832 winning percentage). Many baseball historians don’t consider the league a major league because the St. Louis club was the only one with any legitimate talent. Fred Dunlap, lured to the Maroons when Lucas offered him the highest salary in the league, batted .412. It was eighty-six points higher than his career average.

The farce caused the Union Association to fold after just one year of play. With a quality roster, the Maroons joined the National League the following season. After playing in St. Louis in 1885 and 1886, the team was relocated and became the Indianapolis Hoosiers.

According to historian Joan Thomas, Union Base Ball park had a capacity of about 10,000. An enthusiastic supporter of sports, Lucas had the park surrounded by a cinder track for running and bicycling. The outfield was planted with blue grass and clover. Center field contained a scoreboard, called a “bulletin board” that would display game scores from around the Union Association sent by telegraph.

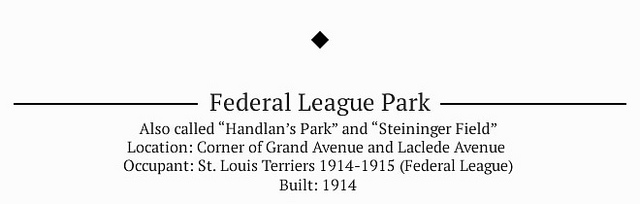

In 1915, a third major league was created to compete with the established National and American Leagues. Deemed an “outlaw” league by its competitors, the Federal league didn’t utilize the reserve clause, which forced a player to be bound to the team that signed him even after a contract expired. This fact, and the lure of higher salaries, caused many big name players such as Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown”, Chief Bender, and Eddie Plank to sign with Federal League Teams.

The St. Louis entry into the Federal League was the Terriers. The team played their games at Federal League Park in 1914 and 1915 before a failed anti-trust suit against established leagues forced the Federal League to cease operations.

Although the league lasted only two seasons, the Federal League delivered one very large contribution to baseball. Wrigley Field in Chicago was originally named Weegham Park, and it was built for the Federal League Chicago Whales. The Cubs didn’t move there until 1916 when the Federal League folded.

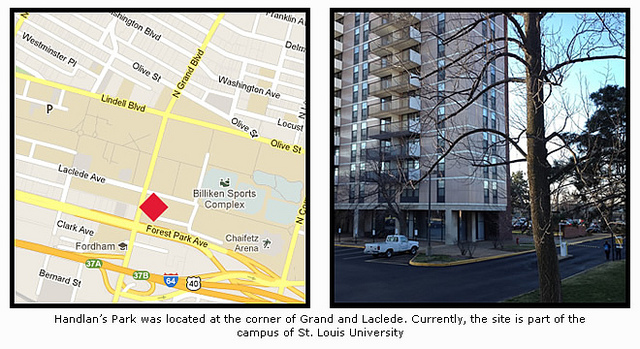

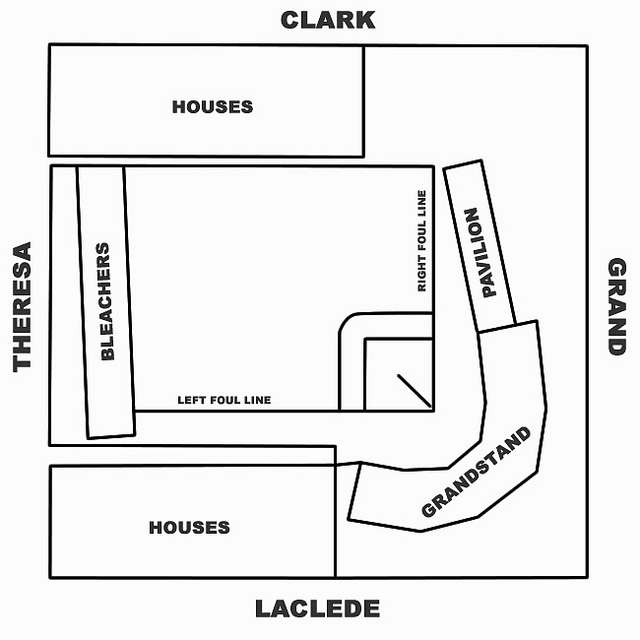

Federal League Park was also called “Handlan’s Park” after the owner of the plot, Alexander H. Handlan. After the Federal League folded, the field was used as the St. Louis University Athletic Field. During the 1920 and 1921 seasons, the St. Louis Giants of the Negro National League played some home games there.

In researching this post, I played a little game where I asked several of my St. Louis friends a simple question. I asked them “Can you tell me the names of the four ballparks that the St. Louis Cardinals have called home?”. It was a fun bit of trivia to throw at them. The results were a bit surprising. Not a single person could name all four. Everyone was able to rattle off “Sportsman’s Park, Old Busch Stadium, and New Busch Stadium”. Not a single responder could give me the name of Robison Field, the ballpark where the St. Louis Brown Stockings/Browns/Perfectos/Cardinals played baseball from 1893-1920.

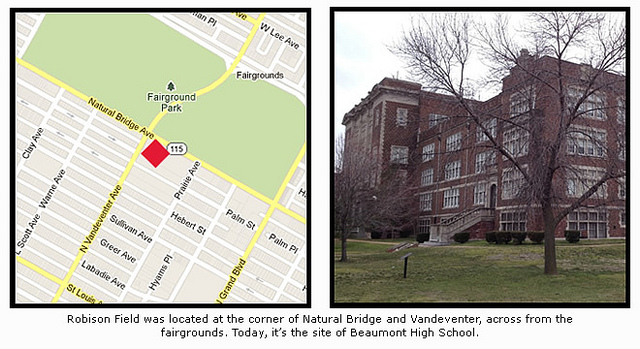

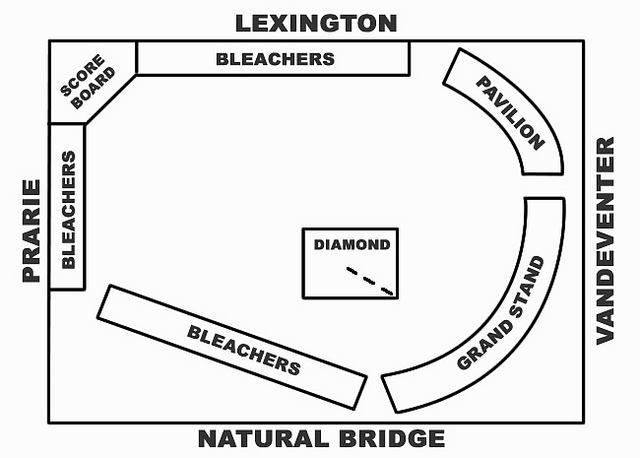

The history of the St. Louis Cardinals could be a library in itself, so for the purpose of this post, I’ll briefly describe how the Cardinals came to play their games at Robison Field. The St. Louis Cardinals started as the St. Louis Brown Stockings. After stints in the National Association (as mentioned in the game against the Red Stockings), the National League, and the American Association, the Browns would become permanent members of the National League in 1892. The team played their games at “Grand Avenue Grounds”, which would officially become “Sportsman’s Park” in 1886. In 1893, the owner of the club, Chris von der Ahe, built and moved the team to a new ballpark named “New Sportsman’s Park” just a few blocks away at the corner of Vandeventer and Natural Bridge. In 1899, the Browns changed their name to the “Perfectos”, along with changing the team colors from brown to cardinal red. The color change was so popular that the team name was changed to the “Cardinals” the following year.

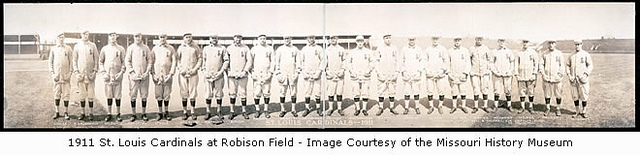

The ballpark at Natural Bridge and Vandeventer would be the home of the St. Louis Cardinals until 1920. It was here that Rogers Hornsby began a career that would make him one of the greatest hitters in baseball history. Cy Young was a member of the 1899 team. Other notable players include the future manager of the Yankees, Miller Huggins, and Bill Doak, who twice led the National League in ERA.

Robison Field is also home to some notable off-field events. In 1911, Helene Britton inherited the Cardinals when team owner Frank Robison died. She became the first female owner of a professional sports franchise in United States history. In 1919, Branch Rickey, the man who integrated baseball, became president and manager of the club.

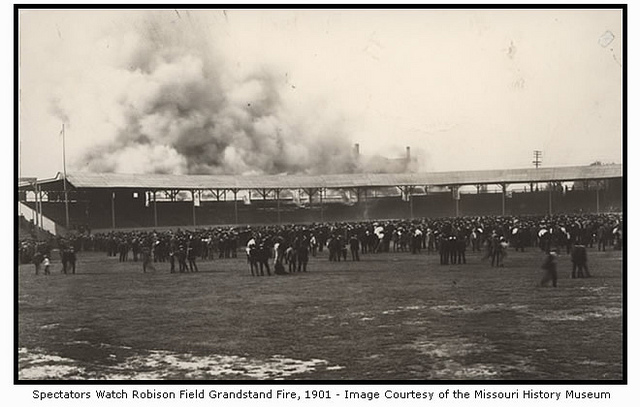

Robison Field was the last professional ballpark that was made primarily of wood. It caught fire numerous times, notably in 1898 and 1901. By 1920, the structure had deteriorated and the team looked to relocate. The last Cardinal home game at Robison Field was played on June 6, 1920.

Robison Field continued to be owned by the Cardinals until the property was sold to developers. In 1926, Beaumont High School was built on the site. Beaumont has since created a rich baseball history of its own. The school has produced dozens of major league baseball players, managers, and coaches. Earl Weaver, the famous manager of the Baltimore Orioles, graduated from Beaumont in 1948.

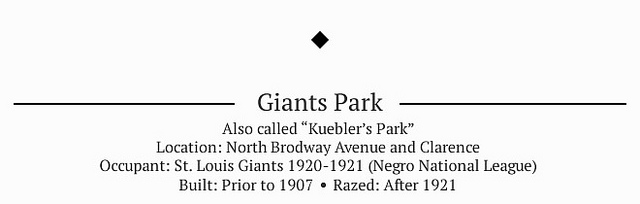

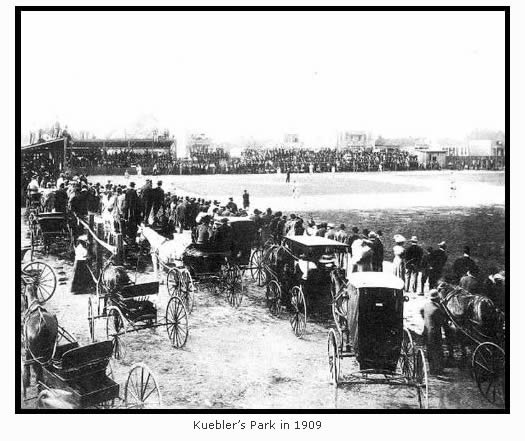

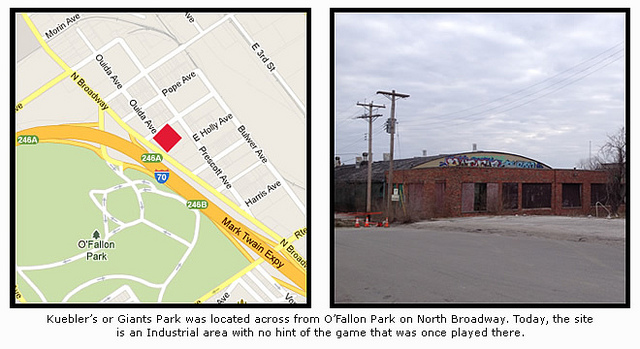

The St. Louis Giants were a Negro League baseball team that competed independently in the early 1900′s. Although the team played at several different ballparks around St. Louis, most of their home games were played at Giants or Kuebler’s Park on North Broadway Avenue.

The St. Louis Giants would become one of the charter members of the Negro National League, the first long-lasting professional league for African-American players. The league was founded by Andrew “Rube” Foster, a legendary man known as the “father of Black Baseball”. The Giants played at Kuebler’s Park for two seasons before being sold, renamed, and moved.

Crowds as large as 5,000 would fill the seats at Kuebler’s Park to cheer on the Giants. Their best player was Oscar Charleston, a future Hall of Famer who batted .436 during the 1921 season.

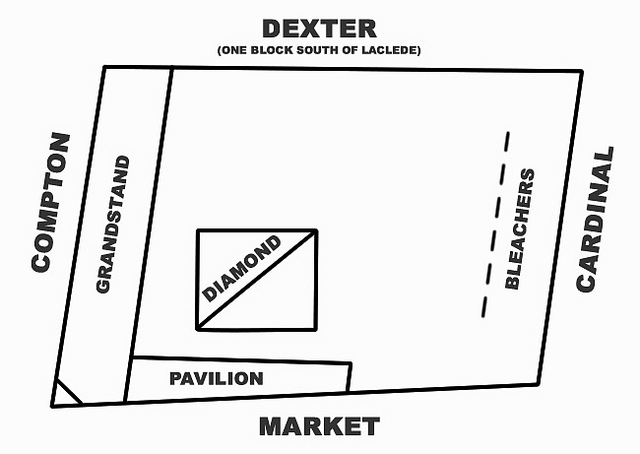

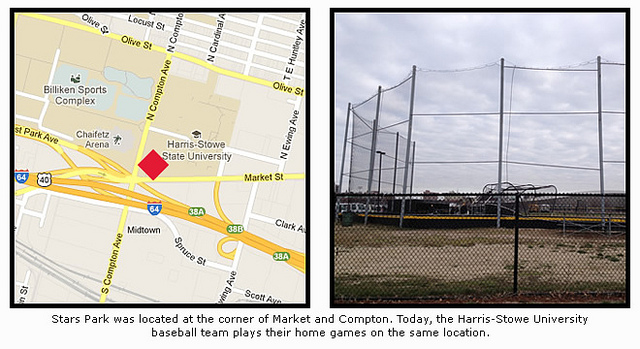

The St. Louis Giants didn’t have to move far when they were sold in 1922. The new owners renamed the club the St. Louis Stars and built them a shiny new ballpark at the corner of Compton and Market. Stars Park, as it would be called, was one of the few ballparks built specifically for a Negro League Team.

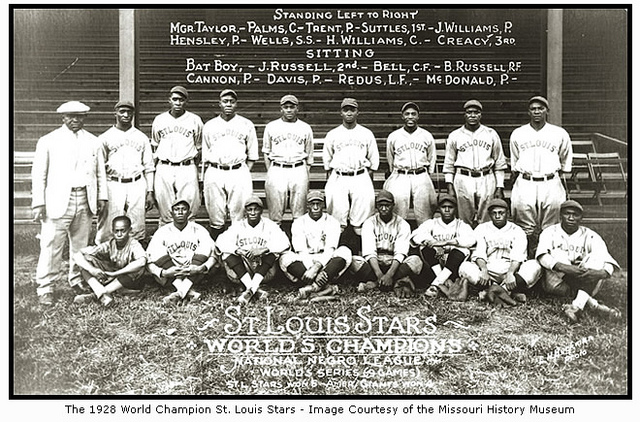

Stars Park is the field where one of the greatest players to ever step on a diamond began his baseball career. James “Cool Papa” Bell started as a pitcher for the Stars in 1921 at the age of nineteen. Like Babe Ruth a few years earlier, Bell began playing outfield on non-pitching days. By 1924, he became the teams full-time center fielder. Considered one of the fastest men to ever play the game, “Cool Papa” Bell led the St. Louis Stars to Negro National League titles in 1928 and 1930.

The famous pitcher Satchel Paige once said about Bell: “One time he hit a line drive right past my ear. I turned around and saw the ball hit his ass sliding into second.”

Along with “Cool Papa” Bell, the St. Louis Stars boasted two other future Hall of Famers. George “Mule” Suttle and Willie “Devil” Wells played with the St. Louis Stars until 1931 when the league folded. The Stars had the best record at the time the league folded, so they were declared champions in that final year. This title is disputed by many baseball historians.

According to baseball historian Joan Thomas, Stars Park had a capacity of 10,000 people. It was known as a hitters park, with a home run to left field only 250 feet away. Today, the same field is used by the Harris-Stowe University baseball team.

After folding in 1931, the St. Louis Stars were reincarnated in 1937 and again 1939 to play in the Negro American League. This team had no relation to the earlier version other than reusing the Stars name. According to Philip J. Lowry in his book Green Cathedrals, the 1937 team played at Metropolitan Park, the same site as Giants or Kuebler’s Park. The 1939 team played at South End Park, which was located on South Kingshighway, just south of Tower Grove Park. In my limited time to research this post, I’ve been unable to find any photographs, diagrams, or articles to further describe these ballparks.

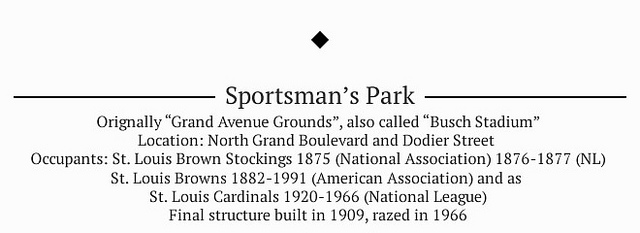

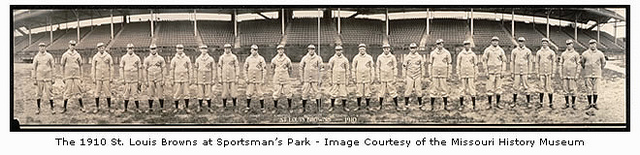

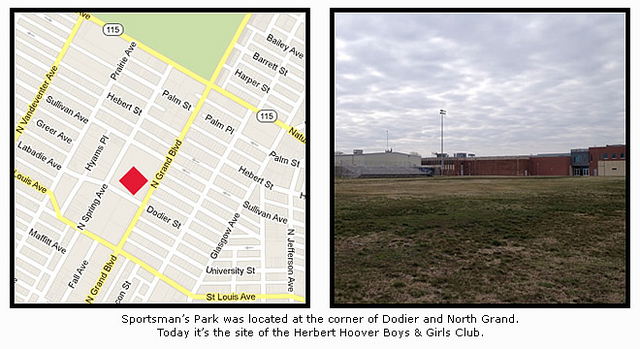

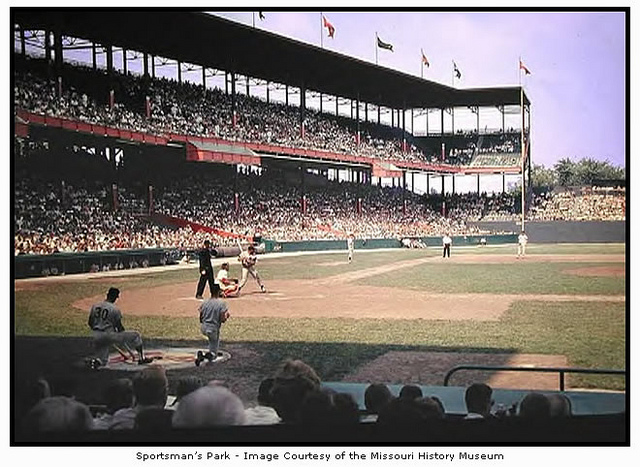

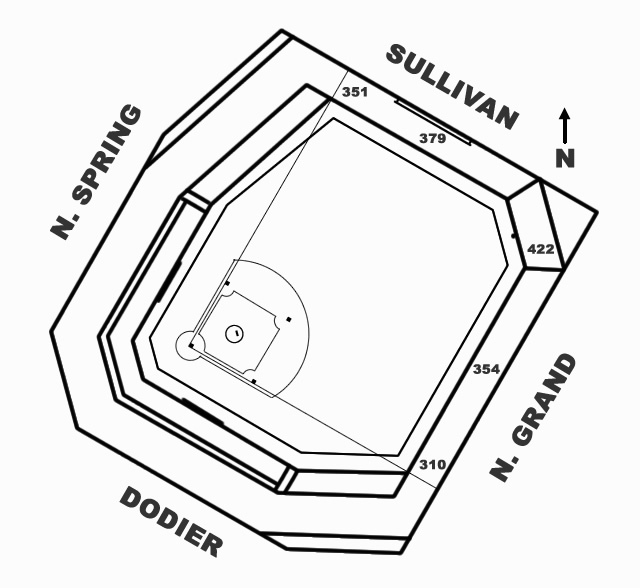

Sportsman’s Park, perhaps the most famous baseball park in St. Louis, began its tenure as the Grand Avenue Grounds in 1867. Few sites in the United States can claim a baseball heritage as rich as the plot of land that sits at the corner of Grand and Dodier in north St. Louis.

Baseball was played at that intersection for over ninety years. Ten World Series and three Major League Baseball All-Star games happened there. The names of great players who competed at Sportsman’s Park is like a Cooperstown roll call: Stan Musial, George Sisler, Lou Brock, Satchel Paige, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Grover Alexander, Willie Mays, Lou Gehrig, and many others.

When Chris von der Ahe moved his club to Robison field and changed the name, the Browns name, colors, and ballpark were now available. In 1902, the Milwaukee Brewers relocated to St. Louis and adopted them all. They built a new stadium, aptly naming it “Sportsman’s Park” For the next fifty-one years, Sportsman’s Park would be the home of the American League’s St. Louis Browns.

In 1920, the St. Louis Cardinals became tenants of the St. Louis Browns when they moved from Robison Field to play home games at Sportsman’s Park. This was the first time in baseball history that two major league teams would share the same ballpark. However, it was the renters that soon began winning pennants. Although more successful during the first twenty years of century, the Browns slid into a long tenure at the bottom of the standings.

Despite a notable Browns vs. Cardinals World Series in 1944, it became apparent by the early 1950′s that St. Louis could no longer support two major league teams. In 1953, the Browns sold the stadium to the Cardinals and relocated to become today’s Baltimore Orioles.

1953 is also noteworthy for it is the year that Anhueser-Busch purchased the St. Louis Cardinals. The owners wanted to change the name of the stadium to “Budweiser Stadium”, but the Commissioner feared a public backlash against a stadium named after a beer. In response, August Busch simply named the stadium after himself. Sportsman’s Park was officially renamed “Busch Stadium”. In a peculiar coincidence, Busch beer was introduced to the American market just two years later.

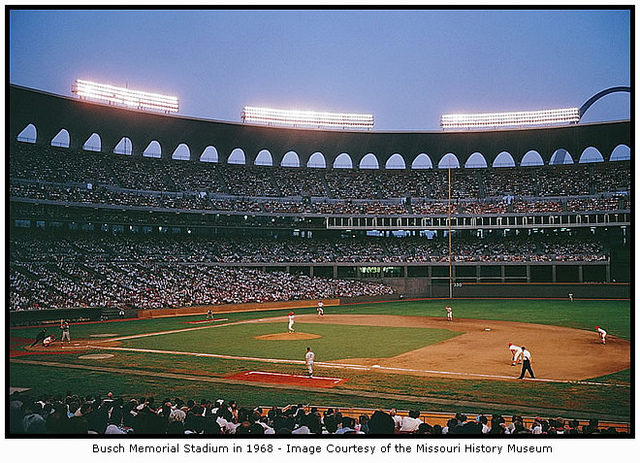

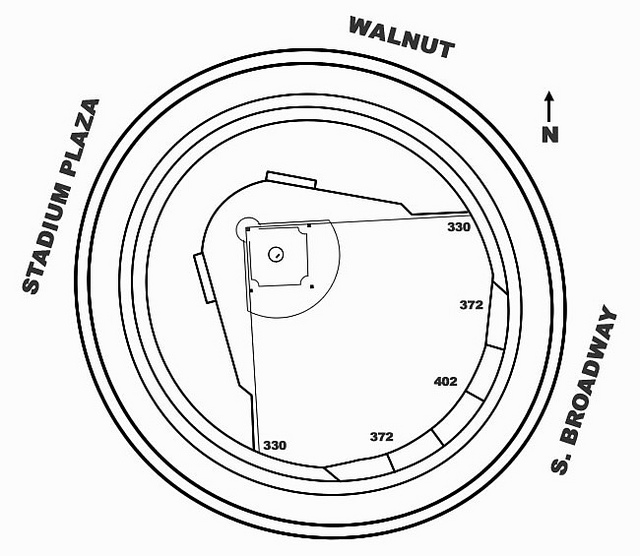

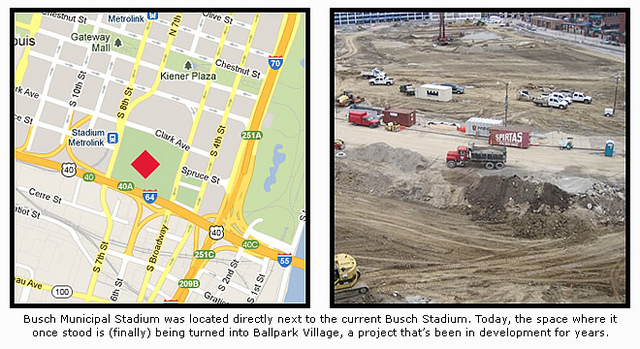

The final ballpark in the Distilled History stadium tour is one that has only been gone for about eight years. What many people now call “Old Busch Stadium” was built in 1966 in downtown St. Louis. The first of the multi-use “cookie-cutter” designs to be built during the 1960′s, Busch Memorial Stadium was the home of the St. Louis Cardinals until the end of the 2005 season.

I was never a fan of the cookie-cutter stadiums (thankfully, they are all gone), but I think St. Louis had the best of the bunch.The ninety-six arches that surrounded the roof added a nice touch to the design.

Old Busch Stadium is also where my darkest baseball memory occurred. The one time that I can say I rooted for the Cardinals like I was born and bred in this city was during the 2004 World Series against the Boston Red Sox. Just as the Yankees failed to do in the American League playoffs that year, the Cardinals couldn’t stop that wretched organization from winning its first title since 1918.

Busch Stadium had a capacity of over 57,000 when it closed in 2005. Old Busch Stadium hosted the 1966 All-Star game and six World Series (1967, 1968, 1982, 1985, 1987, and 2004). The stadium was the site of Mark McGwire’s 62nd and 70th home runs in 1998.

This post first appeared on the excellent Distilled History blog, where Cameron Collins explores the history of St. Louis and its modern cocktails. Please visit his site and read the great items he’s putting together about our city. Check out his post to find out where he found a watering hole on this trip.