On February 11, 1944, at the 8:45 AM student Mass in Saint Louis University’s St. Francis Xavier College Church, Fr. Claude Heithaus, SJ, delivered a homily that would forever change the University. This homily was a calculated act–carefully re-written and revised, shared among trusted confidantes, and distributed to the press—that pushed Saint Louis University into the reluctant role of being a leader in racial justice in education.

On February 11, 1944, at the 8:45 AM student Mass in Saint Louis University’s St. Francis Xavier College Church, Fr. Claude Heithaus, SJ, delivered a homily that would forever change the University. This homily was a calculated act–carefully re-written and revised, shared among trusted confidantes, and distributed to the press—that pushed Saint Louis University into the reluctant role of being a leader in racial justice in education.

The United States was still a country struggling with the issue of segregation. No universities in the state of Missouri were integrated. Although some St. Louis parishes and parochial schools were integrated, most were not. St. Louis Archbishop John Glennon was against integration to the point of bigotry. When the Sisters of Loretto wanted to admit a black Catholic student to their Webster College, Archbishop Glennon blocked the move.

Saint Louis University, at the urging of several priests engaged in ministry to the black community, brought up the issue of integration at a meeting of the Council of Regents and Deans in 1943. Their recommendation: that the University not admit black students, but rather "ascertain objectively the attitude of the students, friends of the University, and graduates of the last twenty years regarding the admission of negro students." This conclusion belies the University’s focus on the political, rather than the moral, implications of integration. Saint Louis University president Fr. Patrick Holloran, SJ, even went so far as to send out a questionnaire to prominent Catholics, asking: “Would you be less inclined to send a son or daughter to Saint Louis University if negro students were admitted?”

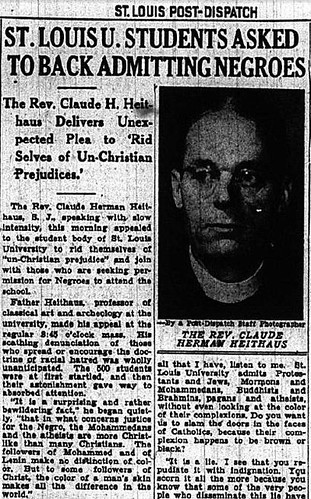

It was within this context of foot-dragging and lukewarm leadership that Fr. Heithaus delivered his homily. Heithaus, a native St. Louisan, served as Professor of Classical Archaeology, as well as moderator of the The University News, the student newspaper. When he saw that he was scheduled to preside at an upcoming student Mass, Heithaus, upset by the stances taken by the University and Archdiocese on race issues, saw an opportunity to act. Speaking with “slow intensity”, Fr. Heithaus laid out a carefully-constructed argument for the integration of the University. Christ, he said, “incorporated all races and colors into his Mystical Body.” He stated that those who call themselves Catholic yet oppose integration run contrary to the example and teachings of Christ, and clearly illustrated the absurdity: “The Blessed Trinity is pleased, and the angels in heaven rejoice, when a negro is united with Our Lord in Holy Communion. But some people say that it is indelicate to kneel beside a Negro at the Communion railing.”

The clarity of his logic and moral power of his argument were undeniable. Fr. Heithaus ended his homily with a call to action. After he asked all to rise for a prayer of reparation for past prejudice and a commitment to racial justice, it was reported that “even the pews stood up.” This display of bravery by Fr. Heithaus, and solidarity by those in attendance, would force the University’s hand on the issue of integration.

Fr. Heithaus had already distributed the homily to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch before delivering it and had prepared for it to be printed in the University News that same day. His act of protest was calculated to receive maximum attention. The speech was re-printed in the African-American press and Catholic newspapers throughout the country, and received much praise. The St. Louis Archdiocesan paper, under the control of Glennon, made no mention of the homily.

At Saint Louis University, Fr. Heithaus experienced an almost immediate negative backlash. As a Jesuit, Heithaus was bound to obedience to his superiors, and his homily was seen as undermining University President Holloran. Holloran gave Fr. Heithaus a direct order to no longer speak to any papers and to turn down any invitations to do public speaking on the subject of race. Heithaus was, in effect, totally censored. Heithaus also had a meeting with Holloran and Archbiship Glennon in which Glennon angrily reprimanded him for his act.

Despite the negative reaction from the University and Church hierarchy, the homily had set the ball rolling for the integration of the University. Just months later the University decided to admit black students for the 1944 summer session. In doing so, Saint Louis University became not only the first university in Missouri to integrate, but the first historically-white university in any of the 14 former slave states to admit black students.

Although his goal was met, Fr. Heithaus did not get a chance to celebrate his victory. Although he was still forbidden by President Holloran to speak on race issues, he did not stop championing racial justice. He pushed for the admission of black students into all-white parochial grade schools, and refused to print in the University News an advertisement for a dance that excluded black students. The Jesuit superiors sided with Holloran in these disputes, and Heithaus was eventually sent away from Saint Louis University and ordered to do penance for his “disobedience,” a judgment which he accepted.

Although eventually allowed to return to Saint Louis University later in life, Heithaus never received an apology for the actions against him, or formal recognition for the vision and resolve he displayed in the integration of the University. It is easy to look back on historical movements with the privilege of hindsight and think of them as inevitabilities—that if Fr. Heithaus had not led this fight, someone else would have soon enough. This view runs the risk of discrediting the individual heroism of those who, despite knowledge of the consequences, were willing to fight against the status quo of an unjust culture.

Saint Louis University can now say with pride that it was a pioneer of racial justice in education, but this is seldom heard. You will not find a street, statue, or building on SLU’s campus dedicated to Fr. Heithaus, despite the tremendous personal sacrifice he made for the betterment of SLU and the greater community. This could be because prominent figures within the University and the Church were so obstinately on the wrong side of history (and morality) regarding race. It is impossible to honor Fr. Heithaus without recognizing the actions of those who fought against him. Doing so would require a display of humility by the University, in recognizing the humanity and fallibility of its own leadership. Taking this step would make a strong statement that the University recognizes its failings on this issue, and is proud to have overcome them.

There is a grassroots movement to bring wider recognition to Fr. Heithaus and his important role in the history of St. Louis University. A group of University professors and stakeholders have founded the Heithaus Haven, named after Fr. Heithaus, as a space for community members to “deliberate on the core values of our institution; to consider how we, as an institution, might live out those values in our own internal norms, practices, and structures; and to identify how we, as an institution, have failed to live out those values in our own internal norms, practices, and structures.” The Heithaus Haven can be found at http://heithaush.blogspot.com.

The Heithaus Haven will commemorate Fr. Heithaus with a re-reading of his homily February 27, at 1 PM in St. Francis Xavier College Church. The homily will be read by Dr. Jonathan Smith, professor of African American Studies at St. Louis University.