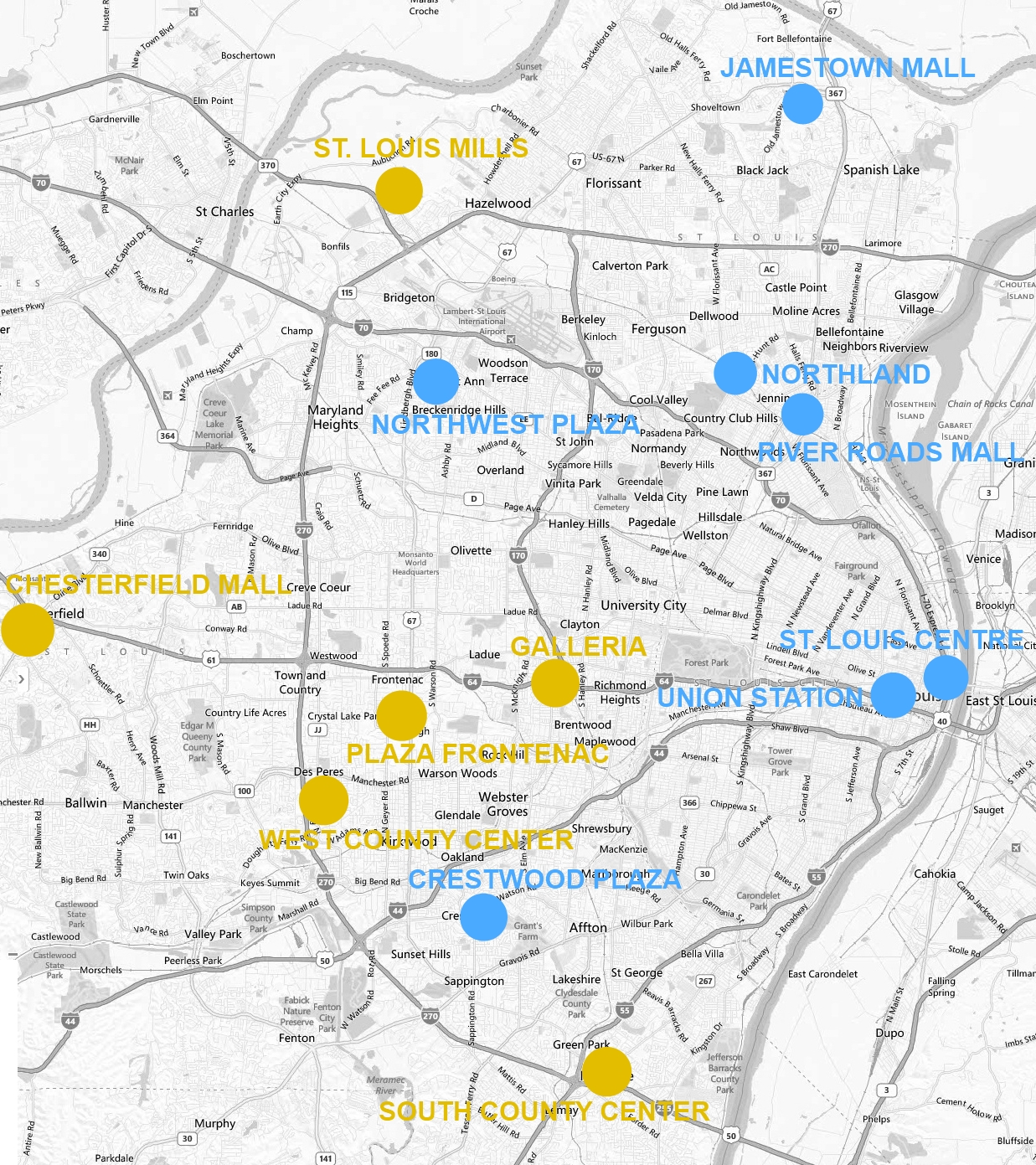

Since the 1950s, the spatial development of the surrounding suburbs has been centralized around the shopping mall. From early incarnations like River Roads Mall to downtown redevelopment projects like St. Louis Centre, shopping malls are unique examples that can help us better understand the demographic and cultural shifts in the American consumer culture over the past sixty years. What follows is a historical analysis of three distinct eras shopping mall development and failure in the St. Louis region.

Since the 1950s, the spatial development of the surrounding suburbs has been centralized around the shopping mall. From early incarnations like River Roads Mall to downtown redevelopment projects like St. Louis Centre, shopping malls are unique examples that can help us better understand the demographic and cultural shifts in the American consumer culture over the past sixty years. What follows is a historical analysis of three distinct eras shopping mall development and failure in the St. Louis region.

City-to-Suburbs: The Rise of Shopping Malls

Shopping malls as we know them today burst onto the national scene in the 1950s as a response to the suburbanization of America during the post-World War II boom. Single-use zoning, shopping centers, highway development, and subdivisions became the core elements of the post-1950s U.S. spatial development.

While suburban residential development began in the mid-late 19th century and early 20th century, in communities such as Kirkwood (1853) and Webster Groves (circa 1892), the commercial and retail sectors did not relocate to the suburbs immediately.

Decentralization of the central business district began in the early 1900s but did not gain full steam until post-World War II, when the retail sector began a mass exodus to the suburbs. Initially, retailers believed that even though the population was moving to the suburbs, people would still visit the city to work and shop. However, after outlying business districts began to gain a foothold because of their close proximity to where people lived, more businesses and retailers moved to the suburbs.

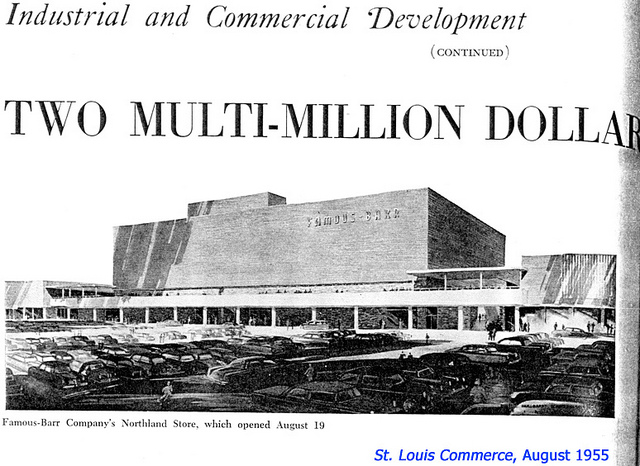

{Northland Shopping Center – image by Built St. Louis}

{Northland opened to fainfare – image via Toby Weiss}

St. Louis’ first incarnation of this “retail-shift” manifested in the form of the Northland Shopping Center that opened in 1955 in Jennings. Within a decade six more shopping centers would open in the St. Louis area.

Northland was anchored by Famous Barr, other tenants included a Woolworths, bowling alley, grocery store, and a post office on its 53-acre site. Northland, typical of other early shopping centers, served as a major bus transfer station for lines that served both the city and county. Northland, designed by the St. Louis firm Russell Mullgardt Schwartz & Van Hoefen, had a Mid-Century Modern design.

Also in 1955, Westroads Shopping Center (later to become the St. Louis Galleria) opened. It was anchored by the St. Louis department store chain Stix, Baer and Fuller.

Many of the first designs of malls were open-air centers with one anchor. It was the first of many experimental designs during this era that developers played with to create a distinctive shopping environment exclusive to the suburbs.

By the late 1950s, suburbia was booming and development started to reach far into the county to the northern and southern municipalities.

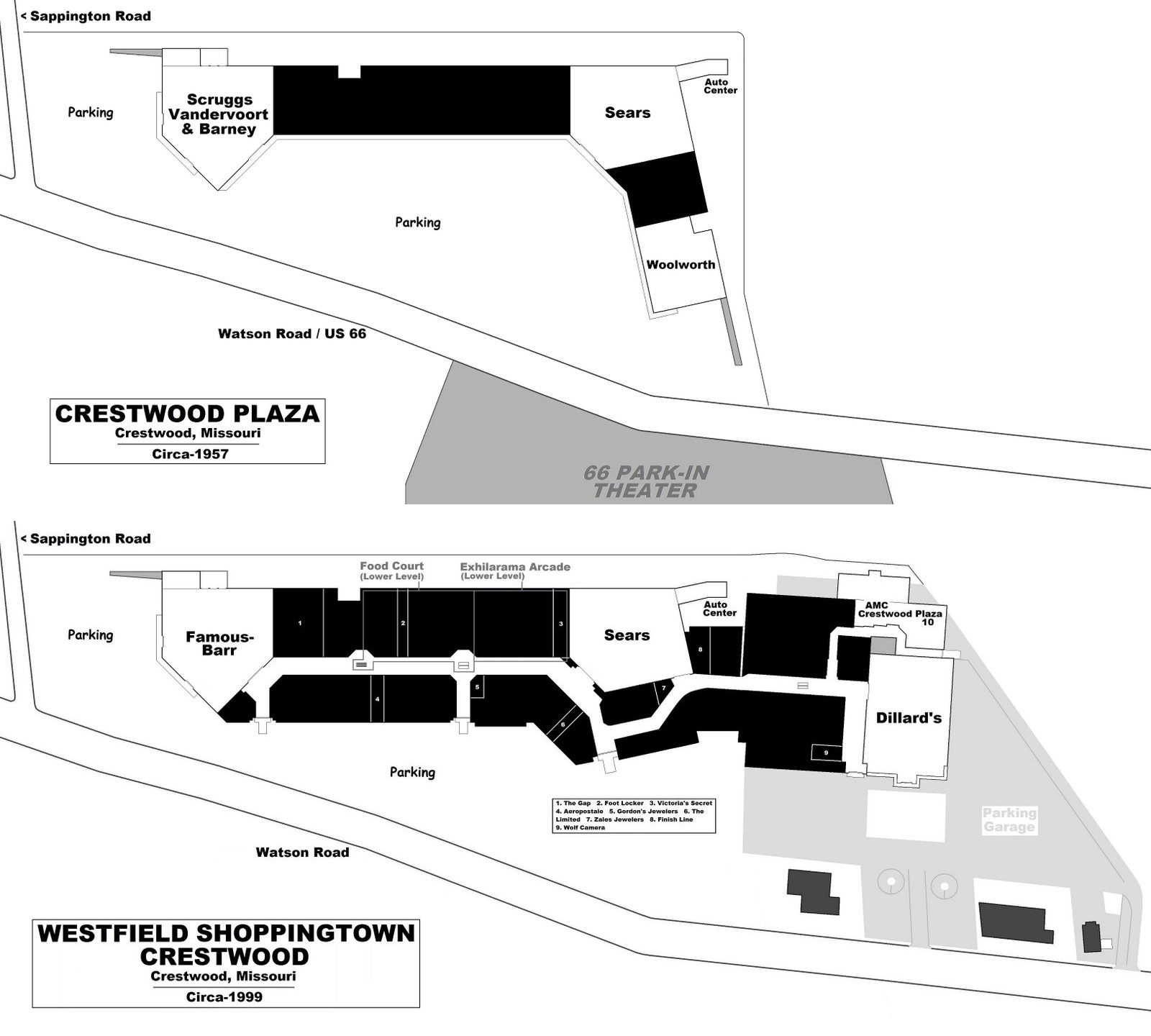

In 1957, Crestwood Plaza opened as St. Louis’ first regional mall. Developed by Louis Zorensky, Crestwood Plaza featured two anchors (Scruggs-Vandervoort-Barney and Sears) with a split-level parking garage. The idea of including two anchors and a split-level parking garage, which allowed patrons to enter on both levels of the mall, were pioneering ideas at the time and would go on to become a standard embraced by malls nationwide. Crestwood Plaza originally opened as an outdoor shopping center that was partially enclosed in 1967 when Stix, Baer & Fuller was added as a third anchor.

{Crestwood Plaza – image by Paul Hohmann}

{development of Crestwood Plaza – image by Mall Hall of Fame}

{aerial image of Crestwood Plaza c. 1970}

{aerial image of Crestwood Plaza c. 1970}

In 1961, River Roads Mall opened a mile away from Northland. It had one anchor, Stix, Baer and Fuller, and other small anchors included Walgreens, Woolworth’s, and Kroger. These two malls, relatively small in size by today’s standards, competed for many decades. The close proximity to each other meant that both failed to become a regional shopping center as the developers had originally hoped.

Then in 1963, South County Center opened. It, like Crestwood Plaza, expanded in 1967 when Stix, Baer & Fuller was added. It was also partially enclosed at that time.

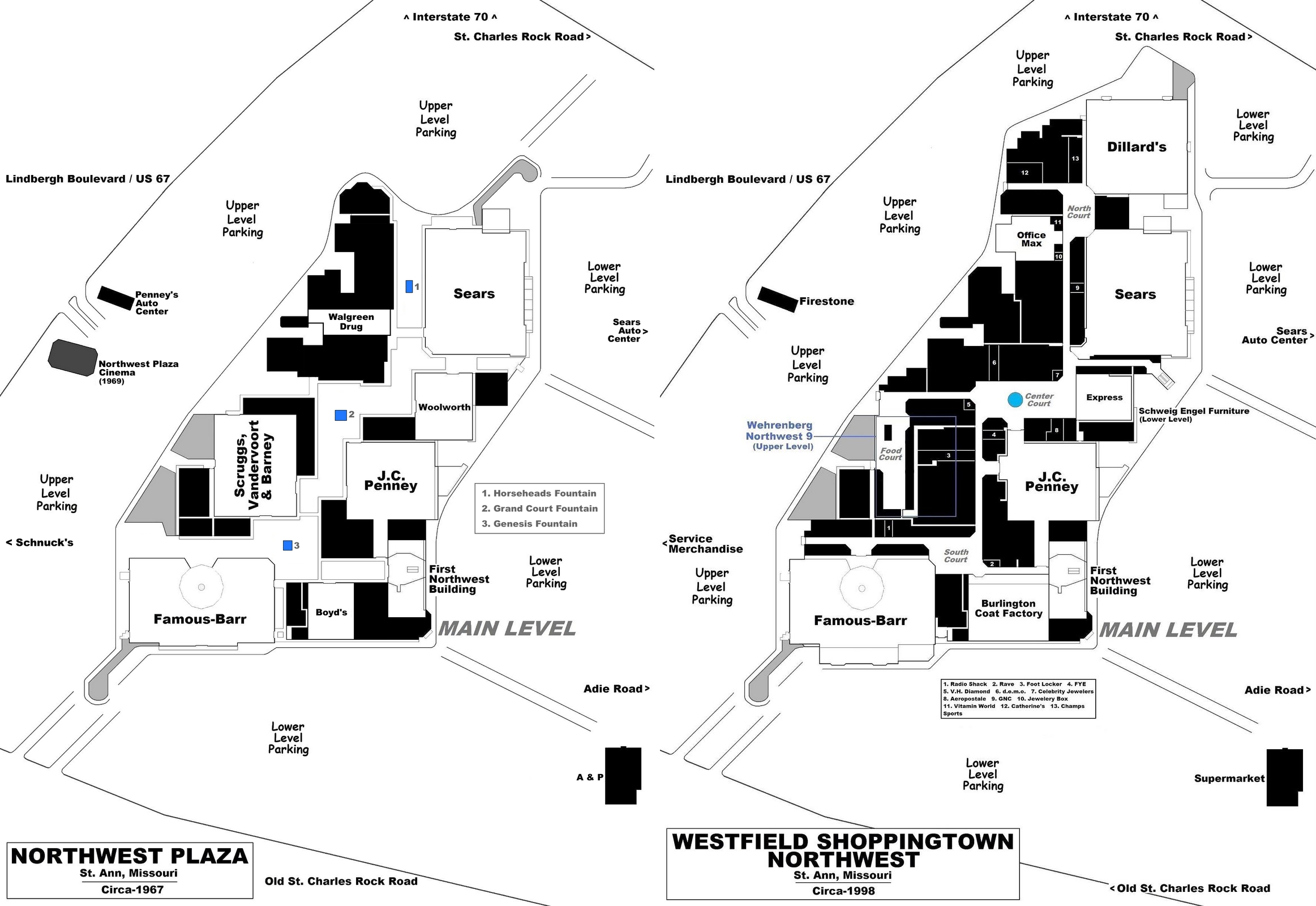

Seeing much success with his experimental design at Crestwood Plaza, Zorensky opened Northwest Plaza in 1965. He chose once again to include new ideas in its spatial layout. Similar to Crestwood Plaza, Northwest Plaza was open-air; it featured four department stores: Famous-Barr, Stix Baer & Fuller, Sears, and J.C. Penny’s. This helped make it the world’s largest shopping center at 1.8 million square feet.

The suburban boom continued throughout the 1960s, which lead to the opening of West County Center in 1969 and Jamestown Mall in 1973. Jamestown Mall was unique in that it was built before residential neighborhoods had developed, since commercial developers hoped to get ahead of planned residential development. It still remains surrounded by a large swath of farmland to the north and failed like many other malls to become a major regional mall.

Three years later, Chesterfield Mall opened. The region now had a total of eight malls and St. Louis had truly embraced not only the American consumer culture, but the spatial layout that came with it.

Kill-off, Expand, and Redevelop

By the 1980s, developers were running out of areas to build malls and were beginning to examine ways to boost their popularity. They found that underperforming malls were going to fail, prospering malls needed to be expanded, and downtown could be a site for a retail renaissance.

This reevaluation was spurred by the changing demographics of the county. Jennings was no longer an ex-urban community—it was inner-ring suburb—and it, along with other early suburbs, were beginning to experience white-flight.

For Northland, Famous-Barr left in 1994 and the Cinema closed in 1997, and by 1999 the Sansone Group was floating plans for redevelopment. Demolition of the mall began in 2005, when the Sansone Group began a $50 million redevelopment of the Northland Shopping Center.

Renamed the Buzz Westfall Plaza on the Boulevard, the former Northland Shopping Center site now contains a Target store, Schnucks (which replaced two stores, one in Dellwood and one in Jennings), Aldi’s, and several other retail locations. It still serves as a bus transfer center.

River Roads also experienced the same fate. J.C. Penny’s became a J.C. Penny’s outlet store in 1984, and Dillards, which replaced the Stix, Baer & Fuller store, closed in 1986. J.C. Penny’s outlet closed in 1996 and the mall was closed that year. It sat vacant for a decade until 2005 when John Steffan’s Pyramid Construction purchased the mall and began to demolish it in 2006, with plans to build 200 single housing units, 15 businesses, a senior’s home, and a city hall facility, according to BuiltStLouis.com. Pyramid, as many of you know, closed, and the project was never finished.

{River Roads Mall – image by Built St. Louis}

{development of River Roads Mall – image by Mall Hall of Fame}

For prospering malls, ownership takeovers by other companies, adding new stores and enclosing the mall became the prime movement.

In 1984, Crestwood Plaza was fully enclosed and 18 stores replaced the former Woolworth’s store. Also that year, Westroads was purchased by Hycel Properties, which tore down most of the mall and began building the St. Louis Galleria. The building was expanded again 1991 when Macy’s and Lord & Taylor opened. Northwest Plaza was acquired by the Paramount Group in 1984 and was fully enclosed in 1989.

For Jamestown, a third anchor, Famous Barr, was added in 1994 during a major expansion of the mall. J.C. Penny’s became the fourth anchor when it opened on April 29, 1995. Interestingly enough, this major expansion of Jamestown occurred simultaneously as the Ford Hazelwood Plant expanded.

{aerial of Jamestown Mall}

{relative footprint of Jamestown Mall – image via Jamestown Mall redevelopment plan}

{development of Jamestown Mall – image by Mall Hall of Fame}

The final major trend in the 1980s was the return of shopping downtown. Cities during this time added suburban-style malls downtown and also revived historic structures as “festival marketplaces.”

These “festival marketplaces” were part of a movement to revive downtown retail by renovating existing structures into entertainment centers that featured retailers, kiosks, restaurants, live music and performances, among many other forms of entertainment. Inspired by marketplaces found in Europe, “festival marketplaces” were an idea led by James W. Rouse and Benjamin C. Thompson.

For St. Louis, the abandoned Union Station was selected to undergo a $150 million renovation and was reopened in August of 1985 as a “festival marketplace.” It featured a renovated grand hall, Omni Hotel, the Grand Basin, and the Midway Marketplace, which featured multiple retailers and restaurants. In addition, surrounding buildings were renovated as office space and a new theater opened under the elevated portion of I-64.

{St. Louis Union Station}

{Union Station Festival Marketplace, 2005 – image by nextSTL Forum user matguy70}

{Union Station Festival Marketplace, 2005 – image by nextSTL Forum user matguy70}

Some retailers included Banana Republic, Talbots, Eddie Bauer, Limited, Nature Company and the Disney Store, according to Paul Hohmann, who worked at the Eddie Bauer store in the early 1990s.

Opening the same year under bright skies, balloons, with Bob Hope cutting the ribbon, St. Louis Centre opened as the largest urban mall in the country. It was atypical of many other shopping malls at the time. It featured a large glass barrel ceiling that let light illuminate the arcade between Dillards and Famous Bar at each end. It also allowed patrons to stare up at the gleaming skyscrapers above.

For St. Louisans, Union Station and St. Louis Centre allowed downtown shopping to be ‘cool’ again, and suburbanites flocked to them when they opened. Mayor Schoemehl’s plan for downtown was working, as it seemed that downtown was finally on its way back from the brink.

End of Malls as We Know Them

There is no other way to put it than by saying that in the mid-2000s, St. Louis malls began to experience a total collapse.

For Jamestown Mall, what was predicted to become a major regional mall become a lone building on the outskirts of the region. By the 2000s, North County’s demographics were changing significantly and could no longer support a mall of this size. Additionally, St. Louis Mills dealt a strong blow to Jamestown Mall when it opened in November 2003.

That same year, Jamestown had a vacancy rate of nearly 30 percent. Carlyle Development Group purchased the mall for $8.8 million with hopes of reviving the mall. They unveiled a $60 million plan in 2004 to renovate and expand the mall; however, the plan was never realized.

Just as Ford announced the closure of the Hazelwood plant and layoff of 1,445 workers in 2006, Dillards closed at Jamestown, proving a detrimental blow to the mall.

Carlyle Development Group announced a new $120 million redevelopment plan on July 28, 2008, just a month before the recession began. It would have been transformed from an enclosed mall into a mixed-use commerce center. The vacant 215,000 square feet Dillard’s store would have been converted into back-office space, and 100,000 square feet of retail space would have been shuttered. The plan included the construction of a senior living space, low-rise office and small service retail buildings.

Sears announced in October of 2008 that they would close their store, leaving only two of the four main anchors left. Currently, Macy’s and J.C. Penny’s Outlet Store remain.

St. Louis County pledged $40.3 million in tax abatement for the project but pulled it in March of 2009 when they learned that Carlyle had planned to auction the Dillard’s space off on April 8.

Currently, St. Louis County is working with the Urban Land Institute to create a plan to redevelop the mall’s site. Various plans have been drafted but nothing has come of it. Some have suggested allowing the mall to die, so that it can be leveled and have nothing replace it, a so-called ‘smart decline.’

Northwest Plaza, once the largest shopping center in the world, closed in 2010. It was the second mall in the region to close since 2006, when St. Louis Centre was closed. What was once home to 210 stores, four anchors, and a movie theater is now a vacant building surrounded by 9,000 parking spots. Rumors floated that it was going to be home to the region’s first IKEA store; however, nothing came of it and the mall remains closed and the region still does have an IKEA store.

{Northwest Plaza – image by St. Louis Patina}

{development of Northwest Plaza – image by Mall Hall of Fame}

A new redevelopment plan emerged on March 15, when it was reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that NWP LLC affiliated with Raven Development proposed tearing down the entire mall except the office tower and vacant J.C. Penny’s store. Three big-box stores and restaurants would occupy most of the new $106 million development. Ground was broken on this project on November 13.

If Jamestown Mall closes, North County will be left without a mall for the first time in over 50 years. Only the large outlet center, the St. Louis Mills, will remain.

Crestwood Court, seeing that the mall was dying quickly, chose to embrace a new idea called ArtSpace, which provided low rents to artists and other entertainment groups to help repurpose the mall. The program did provide some boost to the mall, but the program was short-lived and artists have now vacated the mall along with the last anchor, Sears. The AMC closed this year and the last tenant closed its doors on May 26. Crestwood Court is now the third mall to close in a decade.

The mall is now being prepared for redevelopment by Sierra U.S., which is branding it as “The District At Crestwood.” Parts of the mall will be salvaged, including some of the buildings from the department stores. If built, it will be open-air, similar to the original Crestwood Plaza when it opened.

St. Louis Centre closed in 2006. Quickly becoming an urban eyesore, the mall sparked numerous attempts at redevelopment including that by John Steffen’s Pyramid. His plan called for turning the mall into residential condos, street-level retail, and a teardown of the skybridges. While Pyramid never completed the development as the company closed in 2008, St. Louis Centre’s redevelopment was taken over by Environmental Operations Inc.

{St. Louis Centre open to rave reviews of commercial success – image c. 1985 via Paul Hohmann}

{St. Louis Centre was largely vacant 20 years later – image by Paul Hohmann}

{the festival center concept was praised in planning circles – image via Paul Hohmann}

{twenty five years after opening, the interior mall is large a parking garage, with retail now facing the surrounding streets – image by Paul Hohmann}

{St. Louis Centre – image by Michael Allen}

{St. Louis Centre – image by Paul Hohmann}

{St. Louis Centre today as 600 Washington and the MX (Mercantile Exchange)}

Now dubbed the Mercantile Exchange, the former St. Louis Centre has been renovated into a parking garage with street-front retail, and the sky-bridges have been torn down. Apartments are already filling up in the Laurel—the old Stix, Baer, and Fuller building—while Pi Pizza and the Collective (a retail co-op) have opened, with plans for MX Movies to open later this year.

While the Mercantile Exchange is the newest incarnation of a major effort to boost shopping and dining downtown, the St. Louis Centre has left an indelible mark on the history of downtown revitalization. St. Louis Centre proved that no silver bullet will ever repair downtown. But not all is lost from the former mall: the glass barrel vault ceiling still exists, covering a new parking garage this time.

On the other side of downtown, Union Station’s Midway Marketplace has few mainstream retailers left with the exception of Lids and Foot Locker. The Grand Basin isn’t as lively as it used to be, and the theater is closed. Part of the Midway was shuttered when the hotel expanded in 2010.

Union Station was put up for sale last year and was purchased in October by Lodging Hospitality Management (LHM) for $20 million. LHM is currently in the process of planning a $50 million renovation of Union Station, including an expansion of the hotel, which will shrink the retail space. In addition, conference space will be added, and talks are ongoing for a new transportation museum. In addition, private train service is being mentioned as another amenity that could be offered in a ‘new’ Union Station.

Conclusion

St. Louis malls are unique examples of the spatial development in the United States since the 1950s. They are symbolic of the rise of consumerism in the 50s and 60s, redevelopment in the 1980s and 90s, and the effect of the Great Recession on retail in the different communities in our region. While some malls have been torn down, others boarded up, others quickly dying, and some still succeeding, it would be easy to write off malls as part of our urban fabric. Still, the malls might be one of the most important parts of the our spatial fabric.

Suburban malls might be the greatest opportunity for inner and outer-ring suburbs to develop a “city-center” that can be better connected to the larger region. Increasing development surrounding malls with both high-density housing and transportation connections could help create a better integrated region. This is exactly what the St. Louis Galleria has done as Metrolink now extends to it and the Boulevard St. Louis development has increased density in the area.

However, in some ways, our region still has not learned the lessons that previous shopping malls have taught us. Construction has already begun on two new outlet centers in Chesterfield, both within close proximity to each other and the Chesterfield mall.

Much of the new development that is occurring in our region is not in Chesterfield or in St. Charles. New development is going to be concentrated in the city and inner-ring suburbs as the growing creative class becomes a larger part of our region, choosing to live in more urban areas. It is no secret that our suburbs are only aging and their populations will decrease over time. This is just one among many reasons these centers are doomed to fail.

Just as I have sorted the history of shopping malls into St. Louis into three eras, shopping malls or merely the idea of how and where we shop is entering a new era. The ‘new’ era in some aspects embodies many of the ideas of the ‘old’ era. That is, in the ‘old era’, where small and local stores served the immediate community, and retailers were located in urban and well-connected environments. What is different, though, about this new era is that many existing suburban retail centers, both shopping malls and strip-malls, are going to be retrofitted as the suburban spatial fabric begins to change.

{St. Louis area malls – blue = closed/failed mall, yellow = mall still in operation}