Despite nearly two years of planning between St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker and Rex Whitton of the Missouri State Highway Commission, East St. Louis leaders only learned of the interstate bridge by way of a newspaper article five days prior to the public announcement in downtown St. Louis. Perhaps more concerning for East St. Louis leaders was the fact that the St. Louis-based engineering firm of H.W. Lochner and Company sent their plans to the Illinois Division of Highways in September 22, 1959, but East St. Louis engineers or planners never received a copy.[1]

Despite nearly two years of planning between St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker and Rex Whitton of the Missouri State Highway Commission, East St. Louis leaders only learned of the interstate bridge by way of a newspaper article five days prior to the public announcement in downtown St. Louis. Perhaps more concerning for East St. Louis leaders was the fact that the St. Louis-based engineering firm of H.W. Lochner and Company sent their plans to the Illinois Division of Highways in September 22, 1959, but East St. Louis engineers or planners never received a copy.[1]

The small Illinois city on the eastern shore of Mississippi River had never been part of the new metropolitan conceptualization of St. Louis as the Gateway to the West. Even the Bi-State Development Agency, which was supposed to promote cooperation between parties on both sides of the river, did not schedule any regional meetings prior to January 1960.[2] There had not been a single conference or meeting between any state or federal highway official and any East St. Louis representative.

Doubtless, the bi-state region needed another bridge that could accommodate the growth in traffic that came as the regional population increased and more people bought automobiles. In fact, with approximately 31 percent of the region’s population growth in the 1950s located in the Illinois counties of Madison and St. Clair, Metro East commuters could argue that they needed better vehicular access to the variety of metropolitan amenities – downtown St. Louis, the airport, and the multitude of employment locations. For their part, East St. Louis leaders believed that highways would benefit the city and planners likewise predicted that it would spur development, increase downtown sales revenue, and facilitate population growth.

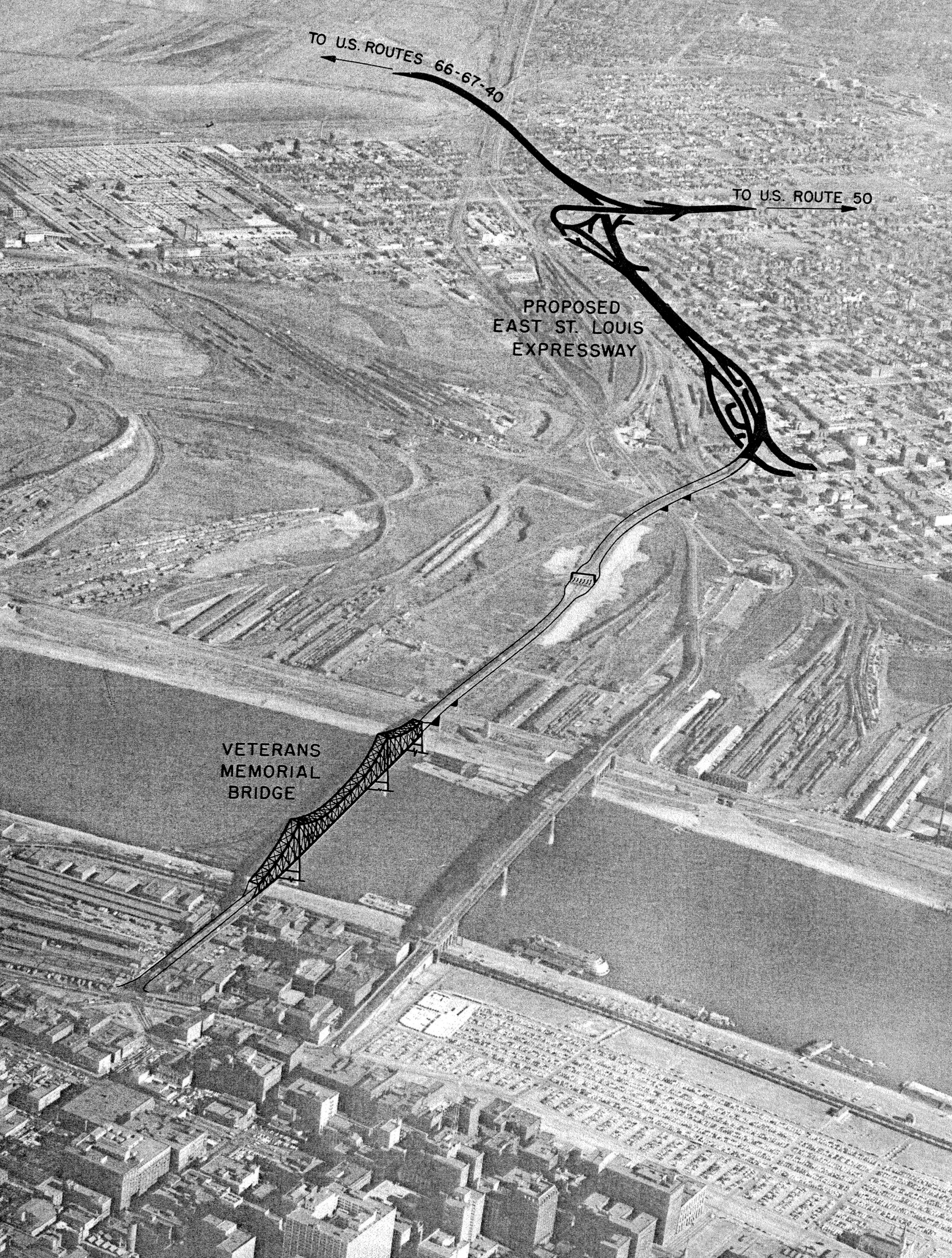

The Metro East Journal and the East St. Louis Monitor celebrated when the city and the state of Illinois began to build the East St. Louis Expressway (Image 1) as the one thing that would put the city’s name on regional maps, literally. An expressway bearing the city’s name signaled that the city of East St. Louis, Illinois had its own distinct identity apart from that of St. Louis, Missouri and was the heart of the growing Metro East. In the mid-1950s the East St. Louis Expressway gained attention from the Chicago Tribune and from 1955 to 1966, the Tribune praised the East St. Louis Expressway as an important piece of an emerging system of highways and interstates that facilitated the circulation of goods and capital between the largest regional metropolitan areas – Chicago, Indianapolis, and St. Louis.[3]

{image 1 – the East St. Louis Expressway directly connected to the Veterans' Memorial Bridge, renamed the Martin Luther King Jr. Bridge}

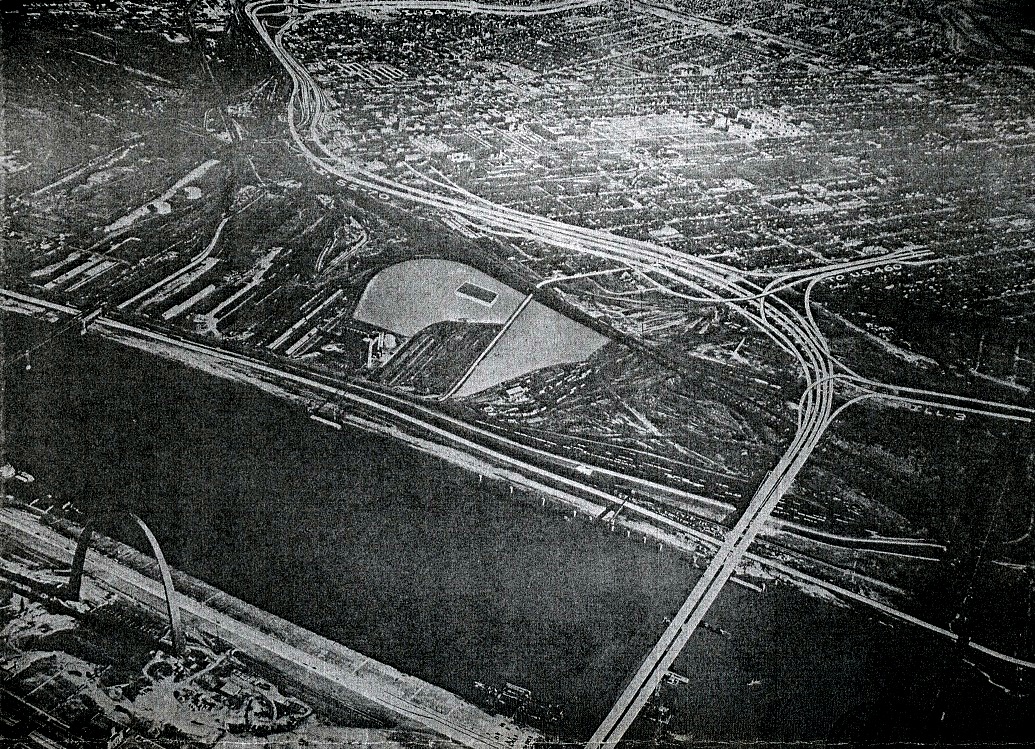

Despite the regional acclaim and local support for highways, news of the interstate bridge shocked East St. Louis leaders and the city engineer immediately released a report protesting the bridge proposal because of its potential physical and fiscal impacts on the city. In the hastily produced Engineers Report of the Proposed Location of Interstate Routes 55 and 70, city engineers complained of issues presented by the interstate bridge and its approach (Image 2). Engineers argued that the interstate bridge was simply “not acceptable to any City Plan under any circumstances.”[4] Moreover, the bridge also posed a threat to a key source of city revenue for East St. Louis: the Veterans’ Memorial toll bridge that had been in operation on the city’s north side since 1949.

The toll revenues earned from the Veterans’ Memorial Bridge (VMB) had been increasing gradually since it opened, and by 1960 East St. Louis had netted as much as $1.45 million annually.[5] The interstate bridge would threaten this revenue stream. In addition, East St. Louis had legally obligated itself not to build another bridge in the city until the bonds that paid for the initial construction of the VMB had been repaid. Doing so might spur a lawsuit from the holders of East St. Louis municipal bonds. The City Council passed an ordinance in 1952 stating,

Until the Bonds secured hereby and the interest thereon shall have been paid or provisions for such payment shall have been made, [East St. Louis] will not construct or cause or permit (where such permission is necessary) to be constructed a bridge, any part of which lies within the corporate limits of the City and which will, or may, divert traffic from the Veterans’ Memorial Bridge with a resultant decrease in revenues derived from the operation of the Veterans’ Memorial Bridge.[6]

Because the proposed bridge might result in East St. Louis breaking its legal commitment to bondholders, the city hired a special defense attorney to “protect its own economic vitality and keep faith with those investors whose private capital has done so much for this area in the building of the East St. Louis Veterans Bridge.” The attorney stressed that East St. Louis had originally built the VMB “upon its own initiative and without financial assistance from the Federal Treasury, the State of Illinois, the State of Missouri, or the City of St. Louis,” but now these external forces threatened the city with what he believed was certain “economic plight.”[7]

{image 2 – the route of Interstates 55 and 70 through East St. Louis}

The fact that East St. Louis had to hire a special attorney in the effort to challenge the construction of a highway through the city revealed the city’s political weakness in the region and what the city engineer had already pointed out: “There is lacking a coordination between the City and the Highway Department.”[8] East St. Louis Mayor Alvin Fields tried to use the engineer’s report to influence the director of Illinois’s Department of Public Works & Buildings, A.E. Rosenstone. Mayor Fields hoped to encourage the overseer of the state highway bureaucracy to take concrete action in the city’s favor rather than accept the Missouri proposal without question.

First, Fields reminded Rosenstone that the City of East St. Louis had not had the “opportunity to make its engineering studies and comments as to where a future bridge across the Mississippi River should be located” until after the Illinois Division of Highways had sent the city the interstate bridge plans in January. “Our engineers, and the City Plan Commission and the engineer of St. Clair County all felt,” Fields contended, “that the Poplar Street location in St. Louis was not the proper location for a bridge across the Mississippi River.” Fields hoped Rosenstone would lobby for a location further south, like that which had been proposed in a 1958 transportation study of the region by the St. Louis based W.C Gilman & Company engineering firm.

East St. Louis engineers had estimated less costly construction on the Illinois side for the urban bypass location and Fields asked that Rosenstone simply rebut the Missouri proposal since “it would not make very much difference to the Federal Government as to the cost being higher in one state or the other.”[9] W.C. Gilman & Company had determined that a bridge built one mile south of downtown St. Louis would be in the best interests of both cities because it would be near the convergence of two expressways on the Missouri side and allow through traffic to bypass both downtown areas and prevent congestion.[10]

Unable to convince Rosenstone to press the issue, Mayor Fields voiced his city’s opposition directly with the federal agency that oversaw interstate highway projects, the U.S Bureau of Public Roads. The BPR administrator’s office sent a curt reply: “This bridge is primarily the responsibility of the States of Illinois and Missouri.”[11] Tallamy had, in fact, already told Missouri chief highway engineer Rex Whitton to proceed with the plans for the bridge location as laid out by St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker. By the time Fields received the response from Tallamy’s office, designs for the on-ramps and off-ramps at the base of the Gateway Arch had been complete for eight months and the bridge location had already become integral to the 1960 Plan for Downtown St. Louis.

The inability of East St. Louis to affect the political process that determined the placement of the highway bridge incensed people on the Illinois side of the river. At the January 1960 public meeting of the Bi-State Development Agency – its first public meeting – over one hundred twenty people from the Metro East showed up, and “almost without exception, speakers from the audience…complained of insincerity by Missouri in its ‘cooperation’ with Illinois.” The planning process that excluded East St. Louis brought some longstanding political tensions to the surface of bi-state metropolitan politics because “much of the two-hour meeting was devoted to criticism of St. Louis.”[12]

The overall opinion was that St. Louis did not care about the Illinois side, and according to a Metro-East Journal reporter, the view of metropolitan development from the perspective of what might be best for the city of St. Louis regardless of the potential detriment to the rest of the bi-state region was indicative of the Gateway City’s “historic attitude toward the Illinois side.”[13] The January 1960 BSDA meeting was the result of a June 1959 recommendation by the BSDA chairman that the agency hold separate meetings on each side of the Mississippi with public officials, business leaders, and organized labor representatives concerning the future activities of the BSDA. Prior to this meeting the agency had operated without any representative, much less democratic, structure.

In 1961, Southern Illinois University professor of metropolitan affairs Seymour Mann argued, “Had an influential and objective organization been in existence to assess the situation, bring the parties together, recommend a location that would best meet the needs of the region as a whole, and use its persuasive powers to win agreement, the matter might have been resolved.”[14]Arguably, the Bi-State Development Agency should have performed that function. Nevertheless, it was not until 1965 that the East-West Gateway Coordinating Council formed and its status as the objective organization that the region needed is debatable. Not really organized as an attempt to ameliorate the tension between parties on both sides of the river, East-West Gateway formed out of necessity: the 1962 Federal-Aid Highway Act required regional partnerships in order receive federal highway funds.

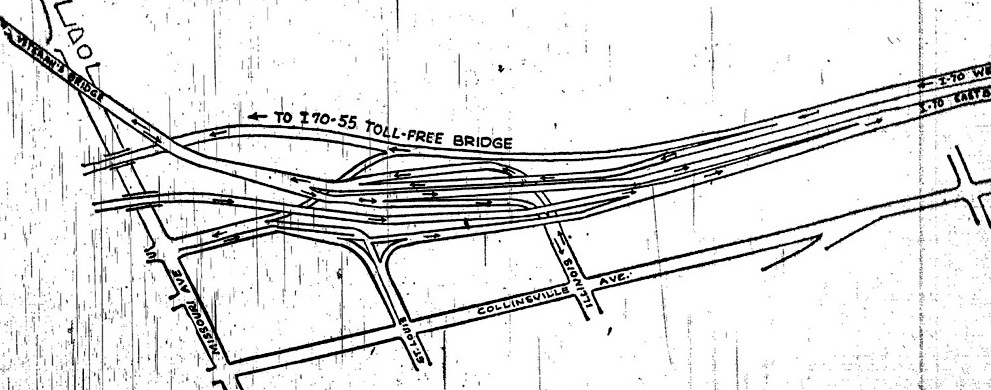

{image 3 – the Metro East Journal showed drivers just how to access the toll-free bridge (and avoid downtown East St. Louis)}

Once traffic began crossing the interstate bridge in November 1967, the city engineer’s fiscal impact predictions became prophecy. An editorialist for the Metro East Journal noted, “Metro-East motorists for the first time since the depression days can drive between St. Louis and East St. Louis without paying a fee.”[15] Because of its central location, the VMB had been the most popular for bi-state commuters and its toll served as a major source of revenue for the City of East St. Louis, but suburban commuters understandably opted for the free route and toll revenues from the Veterans’ Memorial Bridge plummeted. Before the interstate bridge opened, the VMB averaged 27,100 vehicles per day, but a year after the opening of what became known as the Poplar Street Bridge the VMB averaged only 16,100 daily vehicles. The VMB was officially in the red within six months of the interstate opening.

East St. Louis earned $64,242 in toll revenue in May 1968, but operation expenses totaled $67,045. In addition to expenses, the city was scheduled to pay $24,021 to bondholders that month, but was already $26,824 behind on its payments by that point.[16] By 1968, annual toll revenue had plummeted to $791,000, compared to the $2.47 million the city had earned in 1966.[17] Economic plight for the city of East St. Louis had arrived. Between 1960 and 1970, the white population dropped by half as 22,000 left the city. In contrast to the original hope that highways would draw people to live and shop in the city, an editorialist for the East St. Louis Monitor believed that the interstate highway caused East St. Louis to be “lesser populated” and claimed “the deterioration of downtown East St. Louis is obvious.”[18]

Apparently, Metro East consumers were not using the highway exit ramps in East St. Louis, but were instead choosing suburban shopping centers. In 1965, the town of Belleville earned $727,000 in sales tax revenue, but in 1970, three years after the interstate bridge opened, that figure had increased by 57 percent to $1.26 million.[19] East St. Louis meanwhile marked only a 20 percent increase in sales tax revenue from just over $1 million in 1965 to $1.19 million five years later. While it would be wrong to say that the interstate caused the commercial decline of East St. Louis, it certainly made it easier to avoid the city’s central business district on Collinsville Avenue.

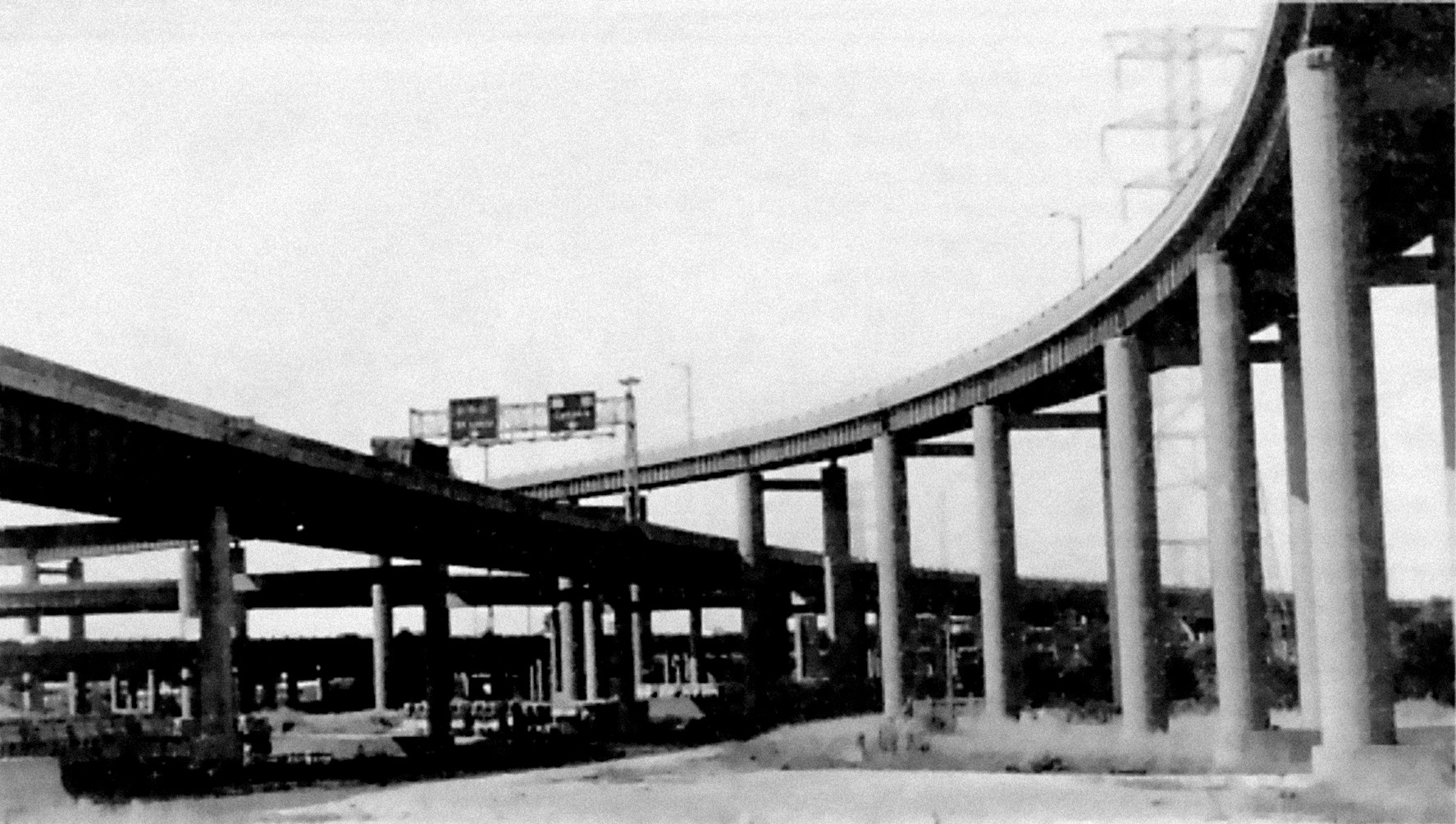

{image 4 – riverfront access – future greenway?}

The inability of East St. Louis to affect the bridge placement decision showed its political weakness in the region and revealed the insignificance of East St. Louis to bi-state metropolitan planning. Perhaps the most significant effect of the interstate was simply its lasting permanence on the East St. Louis landscape. The network of elevated roadways and the complex system of interchanges became, in the words of contemporary planning analyst Robert Mendelson, a “writhing, spaghetti-shaped interstate highway system…a high-speed raceway through desirable riverfront property and through the city as a whole.”[20] From the surface level, the complicated tangle of roadways and the hundreds of concrete pillars that support them fractured the city and prevented access to the riverfront (Images 4 and 5).

The piecemeal removal of this oppressive interstate infrastructure could be a crucial step toward bringing East St. Louis into a newly integrated regional core. Hopefully, the City+Arch+River plan will begin this process of regional reconciliation, revealing the economic potential and social importance of the riverfront on both sides of the Mississippi.

{image 5 – the East St. Louis Spaghetti factory}

[1] Alvin Fields to Rex Whitton, Chief Engineer Missouri State Highway Commission, February 23, 1960. Box 7 File 4, Alvin G. Fields Collection. University Archives, Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville. [Hereafter Fields Collection].

[2] “Bi-State History,” Series 01, Box 01, Folder 1 Bi-State Development Agency Records [Hereafter BSDA Records], Special Collections Washington University Library, St. Louis, Missouri.

[3] Here is a sampling of some of the articles from the Chicago Tribune, “Road Building Plans Outlined For So. Illinois: East St. Louis to Get Its First Expressway,” Dec. 30, 1955, pg 13. “East St. Louis Area Roads To Get 45 Million: State-Wide Program for 1959 Up 10%,” Dec. 9, 1958, pg. A2. “East St. Louis Expressway Is Dedicated: Southwest Completion Date Set,” May 30, 1963, pg. 1.

[4] City of East St. Louis, Engineers Report of Proposed Location of Interstate Routes 55 and 70, n.d., File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection.

[5] “East St. Louis Veterans’ Memorial Bridge Budget Summary” File 2 1965-1970, Box 9 Fields Collection. Annual budget records for the VMB from 1949 to 1961 are unavailable, but the city planning department did leave some sparse monthly records that allow a window into the bridge’s contribution to the city coffers. In June of 1959, the City collected a total of $141,686 in tolls and ticket sales and in August 1961 collected $150,562. “City of East St. Louis, Illinois East St. Louis Veterans Memorial Bridge Statement of Income and Expense Month of June 1959” and “City of East St. Louis, Illinois East St. Louis Veterans Memorial Bridge Statement of Income and Expense Month of August 1961,” File 1 Box 9, Fields Collection.

[6] City of East St. Louis, Ordinance Relating to the Issuance of $15,500,000 Bridge Revenue Refunding and Improvement Bonds Article VII, Section 7.14. File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection. The city had refinanced the bridge bonds in 1952 in order to help fund the construction of the East St. Louis Expressway in 1952, which linked East St. Louis to Springfield, Illinois.

[7] “Statement of Ralph D. Walker, Special Attorney for the City of East St. Louis,” File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection.

[8] City of East St. Louis, Engineers Report, n.d., File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection.

[9] Fields to A.E. Rosenstone, February 22, 1960, File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection. The 1956 Federal Highway-Aid Act created a public funding mechanism for interstate construction whereby the federal government (the U.S. taxpayer) would absorb 90% of interstate highway construction costs and states would pay for the remaining 10%.

[10] According to Owen Gutfreund, bypassing urban cores was one of the main objectives of America’s interstate designers. See his Twentieth Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape, (Oxford University Press: New York 2004), 46.

[11] Fields to Bertram Tallamy, May 9, 1960. Armstrong to Fields May 26, 1960. File 4 Box 7, Fields Collection.

[12] “Illinois Blasts Missouri,” MEJ, January 26, 1960.

[13] “Area Distrusts Missouri, Bi-State Members Told,” MEJ, January 26, 1960.

[14] “Regional Progress Inc.,” Folder 3 Box 5 Series 5 Seymour Mann Files, East-West Gateway Coordinating Council Records, Special Collections University Archives Washington University Library, St. Louis, Missouri.

[15] Metro-East Journal, “Bottleneck to Progress Removed,” November 10, 1967, pg. 12.

[16] “City of East St. Louis, Illinois East St. Louis Veterans Memorial Bridge Statement of Income and Expense Month of May 1968,” File 2 1965-1970 Box 9 Veterans Memorial Bridge, Fields Collection.

[17] “East St. Louis Veterans’ Memorial Bridge Budget Summary” File 2 1965-1970, Box 9 Fields Collection.

[18] East St. Louis Monitor, “The Withering of Downtown,” December 12, 1967.

[19] Ruben L. Yelvington, East St. Louis: The Way It Is (Mascoutah, IL: Top’s Books 1990), 214.

[20] Robert Mendelson, East St. Louis: The Riverfront Charade (Southern Illinois University: Edwardsville, IL 1970), 3.

____________________________________________

*this post first appeared on Michael's new Poetries of Place site