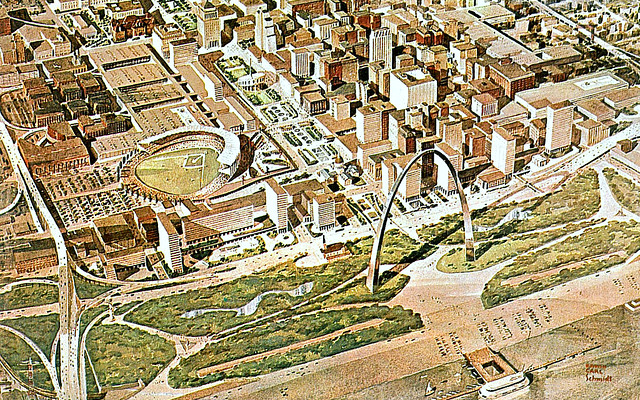

{the interstate bridge at the bottom left provides travelers with a grand entrance into downtown, guiding them through the Gateway to the West}

The Poplar Street Bridge that now carries Interstates 64, 55, and 70 was part of an urban redevelopment vision for St. Louis centering round The Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (JNEM). City boosters and public officials, taking a cultural clue from America’s pioneers, wanted St. Louis to become a place worth exploring in its own right. When St. Louis began receiving federal funds in 1958 to build the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial – a six hundred foot monument commemorating America’s continental conquests and territorial triumphs – public officials and private industries began reimagining the economic future of St. Louis and began an earnest strategy to brand the city as the Gateway to the West.

Public officials and boosters were joined by private universities (St. Louis University and Washington University) and the region’s largest R&D corporations (notably McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and Monsanto Chemical Corporation) in planning the city’s postwar development policy, which not only directed investment flows but also determined geographic patterns of development.[1] This public-private development partnership solidified in the postwar years, and by the late 1950s both groups believed that they needed to overcome regional transportation difficulties in order to grow St. Louis and bring it into the modern era. Private companies sought to ease the difficulty of traveling from new suburban corporate campuses to the more centrally located research universities, as well as between existent downtown office towers and recently constructed residential suburbs.[2] Public officials also wanted suburban residents to easily travel to and from urban tourist destinations, and the Arch was obviously the most important. The city’s three major expressways radiated from the JNEM site to the northwest, west, and southwest, closely resembling the westward vision laid out by Harland Bartholomew in the 1947 Comprehensive City Plan.[3] But the public officials and private corporations that played a key role in St. Louis’s postwar development policy believed that the region would need a modern highway system that could tie together everything in between the JNEM riverfront site and Monsanto’s industrial park about thirteen miles away in St. Louis County.

Both public and private interests in St. Louis understood that they were more likely to achieve their local transportation goals if they could affect transportation planning decisions at the state level, and, fortunately for them, St. Louis had a mayor who was well respected within technocratic circles. As a former professor of engineering at Washington University, St. Louis mayor Raymond Tucker took it upon himself to carry the torch for an interstate highway to travel from the riverfront west through the central corridor of the city and into St. Louis County. Of critical importance to Mayor Tucker was a grand entrance for motorists traveling west into the Gateway City. Tucker wrote to Missouri Chief Highway Engineer Rex Whitton in September 1958, proposing the construction of a bridge across the Mississippi River at the base of the national monument, which would connect to the existent Daniel Boone Expressway. Tucker learned, however, that highway engineers were already in the process of studying where to build a bridge in order to alleviate traffic congestion on the region’s three river bridges. Highway engineers had determined that the ideal location for a new bridge would be one mile south of downtown St. Louis at the convergence of the southwesterly Ozark Expressway (later Interstate 44) and the north-south Mark Twain Expressway (later Interstates 55 and 70). While Tucker agreed that the “new bridge should be south of the business district,” if built a mile from downtown it might act as an urban bypass – exactly what the mayor and the city’s growth visionaries wanted to avoid. Tucker proposed that the bridge be built near the Arch and “as close to the core as possible” so that westward traveling motorists would receive a grand skyline view of the Gateway to the West as they entered the city; which might entice drivers to choose the next exit and explore the city’s tourist attractions.[4]

Missouri highway officials were able to ensure that the project proceeded as proposed. In fact, Missouri’s chief highway engineer Rex Whitton was quite influential within the nation’s federal highway bureaucracy. Whitton served as president of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO), which worked directly alongside the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) in the construction of the nation’s interstate system. According to historian Owen Gutfreund, the AASHO and the BPR were “the mandated gatekeepers and overseers” of the funding, planning, and construction of the American interstate system.[5] Whitton’s position as AASHO president put him in direct contact with the BPR administrator, B.D. Tallamy. Both graduated from the University of Missouri’s College of Engineering and had become the two most powerful highway bureaucrats in the country at this time. After the two met and discussed the bridge proposal, Whitton confirmed to Tucker, “Tallamy…does not in any way object to us proceeding with the location of this bridge and the preparation of the plans.” The state of Missouri had approval from the highest highway official in the country to begin planning St. Louis’s interstate entryway. Because Whitton had insisted that the matter “be kept confidential” Tucker did not go public and instead assembled a three-person professional design team—Eero Saarinen, architect for the National Park Service; Myer Ableman, Urban Area Engineer for the Missouri State Highway Department; and John Poland, Director of the St. Louis City Plan Commission.[6]

By October 1959, Tucker’s location for the bridge and the attendant design details of downtown on-ramps, off-ramps, and exchanges had been determined (See images). On January 14, 1960, Frank Kirz, the board president for the Missouri Public Service Commission, stepped in front of a small gathering of civic officials, business leaders, and reporters in St. Louis and announced that Missouri would build a “Free Bridge at the focal point of our city’s expressway system.”[7] The bridge and the downtown interchange, Kirz celebrated, “involves only an acre and one-half of Jefferson Memorial property.” It quickly became an integral piece of the 1960 Plan for Downtown St. Louis.

{the on-ramps and off-ramps in this image reveal the hopes that the highway would make it easier for drivers to visit the city’s attractions}

While there is currently a substantial amount of attention and energy directed at mitigating and resolving the negative effects that this decision had on downtown St. Louis, there is little if any concern for the impact it had on East St. Louis, Illinois. Understandably, citizens, St. Louis enthusiasts, and urbanists of all political stripes want to make St. Louis more vibrant, more accessible, more livable. The City to River organization is the most vocal and engaged outgrowth of this sentiment. Concerned with how the sunken Interstate 70 has cutoff pedestrian access between the riverfront and downtown, City to River aims to “reopen the region’s front door.” But what about the back door? Do we on the St. Louis side care not about East St. Louis?

If history is any guide, we should take a proactive approach to incorporating East St. Louis into our regional development strategy. What ended up becoming the PSB stretched over the Mississippi River into East St. Louis, but neither St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker nor Missouri chief highway engineer and AASHO president Rex Whitton, paid the neighbor’s fortune any mind. As it turned out, East St. Louis did not fit with St. Louis’s new image as the Gateway to the West, and, moreover, the city was unimportant to the vision for westward development as espoused, proposed, and funded by St. Louis’s most powerful private and institutional interests. The interstate proved quite consequential for East St. Louis. More to come on that story in future entries.

[1] Joseph Heathcott and Maire Agnes Murphy, “Corridors of Flight, Zones of Renewal: Industry, Planning, and Policy in the Making of Metropolitan St. Louis, 1940-1980,” Journal of Urban History 31:2 (January 2005): 151-189, 156. Their analysis found that St. Louis University, Washington University, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, Monsanto Chemical Corporation, Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, Anheuser-Busch, Ralston Purina, Union Electric, and Emerson Electric were the most influential interests behind specific geographic patterns of economic investment in postwar St. Louis and St. Louis County.

[2] St. Louis University is in the Midtown area of the City of St. Louis. Washington University is partially located in St. Louis, unincorporated St. Louis County, and University City, one of many municipalities that share a political border with the city. St. Louis Commerce Magazine reporter Bill Beggs Jr. covered the recent developments of the central biotech corridor in the June 2008 issue, which can be found here (http://www.stlcommercemagazine.com/archives/june2008/cortex.html). Specifically, Beggs covers CORTEX (The Center of Research, Technology and Entrepreneurial Exchange) and the emergent “Biobelt.” As Beggs states, “CORTEX is a unique public-private partnership that is an outgrowth of the region’s original plant and medical sciences strategy.” He dates this strategy only as far back as the year 2000. For a more exhaustive (and critical) history see the article cited above by Heathcott and Murphy.

[3] The urban tourist destinations were the St. Louis Science Center, the St. Louis Zoo, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Missouri Botanical Garden, and more. For Bartholomew’s expressways see Mark Abbott, “The 1947 Comprehensive City Plan and Harland Bartholomew’s St. Louis,” in St. Louis Plans: The Real and the Ideal St. Louis, ed. Mark Tranel (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press 2007), 137. In 1959, St. Louis proudly displayed the region’s modern highway system in The New Yorker. The nextSTL blog posted this ad to its Facebook page just a few days ago.

[4] Raymond Tucker to Rex Whitton, September 30, 1958. Folder Highways – Poplar Street Bridge, Box 13 Series 2 Raymond R. Tucker Papers Second Administration Office Files, University Archives, Department of Special Collections Washington University Libraries, St. Louis, Missouri. (Hereafter Tucker Papers). Hardly an image that sells the “idea” of St. Louis to the global public does not contain a panoramic skyline photograph.

[5] Owen Gutfreund, Twentieth Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape (New York 2004), 56.

[6] Tucker to Whitton, September 30, 1958. Whitton to Tucker, October 20, 1958. Whitton to Tucker, January 19, 1959. Folder “Highways – Poplar Street Bridge” Box 13 Series 2 Tucker Papers.

[7] “Statement from Frank Kirz, President Board of Public Service Highway Department Public Hearing (Poplar Street Bridge) January 14, 1960.” Folder “Highways – Poplar Street Bridge” Box 13 Series 2 Tucker Papers.

*this post first appeared on Michael’s Poetries of Place site