Both the Lafayette Square and the JeffVanderLou “Neighborhood Plans” were adopted by the City of St. Louis in 2001, and as such it makes sense to compare and contrast these two considerably divergent documents.

Both the Lafayette Square and the JeffVanderLou “Neighborhood Plans” were adopted by the City of St. Louis in 2001, and as such it makes sense to compare and contrast these two considerably divergent documents.

Without question, the issues affecting Lafayette Square and JeffVanderLou are extraordinarily different. For starters, the demographics are 99.2% African-American/Black for JVL, yet 28.1% for LS. The median income in JVL is just over $18,000; in LS it’s more than $45,000. This is about as stark a contrast between poor black and (more) affluent (mostly) white as one can get in the city limits. Within JVL, segregation and urban poverty issues are front and center, both on a day to day basis and within the plan; for LS, not so much.

In the JVL plan, social/community issues are given heavy weighting. The JeffVanderLou Neighborhood Plan is ‘triple bottom line’ planning document designed to tackle all of the issues affecting the neighborhood. Land use and economic planning are addressed alongside issues like education/training, child care, and crime/safety. The LS plan, by contrast, addresses form and function far and above any social issues. Amenity and preservation of the built form are the focus here. Any social problems that may be prevalent in the area are not given much consideration in the plan. Succinctly – the JVL plan is more about ‘People’, where the LS plan is almost exclusively about ‘Place’.

{a typical scene in the JeffVanderLou neighborhood}

{a typical scene in the Lafayette Square neighborhood}

The JVL plan is heavily performance-based and relies on broad motherhood statements to accomplish its objectives. Detailed plans for specific areas do exist, but there are few prescriptive elements. The LS plan is almost entirely prescriptive, clearly outlining design requirements both in the public and private realm – even getting into micro-management from time to time (see p.41). The plan generally sets out clear design guidelines that are to be adhered to going forward.

In subject matter, the JVL plan seeks to be aspirational and game changing. The plan proposes things like ‘thematic districts’ (for tourism/eco dev purposes) and major changes to land-use patterns and zoning. The LS plan, again in complete contrast, is about management and preservation. The plan seeks to push development and design to a preferred point, with high emphasis on amenity and connectivity. In essence, where the JVL plan is trying to stem the tide of decline, the LS plan is working to preserve and enhance its character in the face of development pressures.

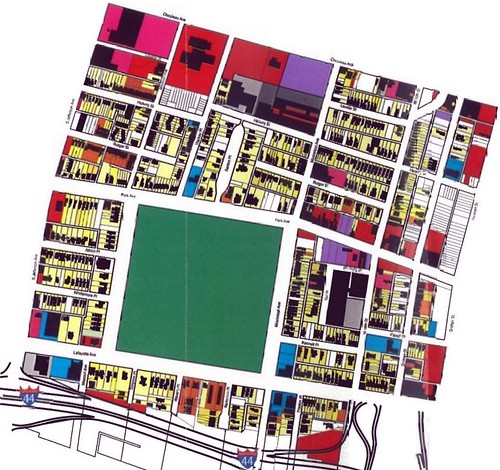

{JVL – building outlines in plan area}

{Lafayette Square – building outlines in plan area}

It is impractical to critique plans so divergent on their content – after all, the phrase “different strokes for different folks” applies here. For example, JVL does not need prescriptive housing requirements – it needs vacant lots filled; while LS doesn’t need to devote space in its plan to teaching its residents how to be financially secure (though it wouldn’t hurt). Still, there are clearly faults in the JVL plan in comparison to the LS one.

As presented on the STL Planning Documents website, it is a challenge to read the JVL plan. It is effectively broken up into 4 sections:

- The Plan for Action, which is essentially an action plan comprised of social/community initiatives with some land use actions

- An existing conditions report

- An urban design/economic analysis section (more design focused)

- A ‘bookend’ sections that covers policy, zoning, compliance matters

The ‘Plan for Action’ is effectively a summary document of the existing conditions report and urban design analysis, but it is not comprehensive and one has to read every single section/report separately. This is somewhat unusual, as most plans have a comprehensive summary document that addresses any and all background reports/appendices and merely refers to them for more detail. This leads to some confusion as to what the emphasis of this plan is on – place or people? It eventually becomes clear that the plan is comprehensive, but one would not gather that merely by looking at the action plan.

This format would not be so bad if each report was clearly organized; however, they are not. Within the ‘bookend section’, there is a table of contents that is at best, slapdash. One has to flip back and forth between non-consecutive sections to find the information one is looking for. For example, in the TOC, ‘Building Conditions’ are on p.24 of the Existing Conditions report, while Community Institutions/Public Facilities is 10 pages earlier, in the same report yet listed later in the TOC. As a reader, this is frustrating and eventually leads to someone reading all of the reports, a process that is longer and repetitive. A single, comprehensive document with attached appendices would have been much cleaner and easier to read.

Continuing with formatting, in the electronic version of the JVL action plan, pages 2-3 are repeated; after p.23, p.5 of the executive summary appears, and pages 42-43 are missing (or omitted). This is careless and significantly affects how the document is read. Furthermore, on p.16 it appears there is a table missing without any explanation. Within the strategies and implementation sections, the timing has no perspective – does short mean two years? Does long mean five? What is the lifetime of the document? That information is not provided. Actions need to be prioritized as well. The list of actions here are too great to tackle at once. It is assumed that an ‘immediate’ action will be started before a long term action – but what are the top priority projects for the community?

Lastly, for being written in 2001, there is no excuse for the entire document to have been scanned (3-hole punches are clearly visible). There had to have been an electronic file and that should be what is available. The scan is fuzzy and many tables are extremely hard to read. Unfortunately, all of this could have been easily avoided. Within the second page of the ‘bookend’ introduction, a single bound document was to be made available in electronic format. Was this delivered? If not, why not? And if so, why isn’t that the public document? (Note: the JVL plan has been combined into one document and posted below)

By comparison, the LS plan is a simple, single 75 page document with clear headings and concise formatting. All the pages are included, in order, and references clear and logical. Lifespan is introduced quickly at p.5, timing/prioritization is noted in the implementation section. One can pick this document up and within seconds, understand the focus and find exactly what one needs. There are some maps in the early portion of the LS plan that are totally illegible (p.11-12), which is inexcusable. However, aside from those pages, the LS plan is much easier to read than the JVL plan.

{JVL – Master Plan outline}

{Lafayette Square – Master Plan outline}

It is easy to dismiss these criticisms as hypercritical, but remember that these are public documents. A good public document should always be easy to pick up and read. At the emotional level, a plan that looks sloppy makes it seem like people didn’t care regardless of whether they did. This can translate to less buy-in at all levels. Bluntly, perception matters.

At a practical level, people have to be able to read and digest plans quickly so they can propose developments consistent with the plan, and conversely, so the civil servants can easily assess proposals against it. The longer it takes to read the slower processes become, and to a developer time is money. Certainly, this alone likely isn’t enough to turn a developer off of a project entirely, but it doesn’t help matters.

This is a shame, really, because there are a lot of good things in the JVL plan. It addresses, with quite substantial rigor, a wide variety of issues that are tangential to the planning profession but nonetheless are critical to making a successful place. Its focus on embracing and preserving the local history and built form is a welcome change from previous plans that called for clearance of ‘old’ housing stock for new development that would never come. Here, only housing too far gone to be saved is noted for demolition, and only then for properly designed infill. The goal of returning street-based retail to Jefferson and MLK at the expense of strip-mall development is again, a welcome change. In short, as a ‘plan’, it’s a very good one. The content potentially provides more promise than the LS plan – but it’s just so hard to get past the jumble.

This is not to say the LS plan is without fault. The plan overemphasizes design and building guidelines/requirements, with little to no regard for wider economic or social issues. This leaves the neighborhood vulnerable to regional/national economic shifts. It’s also a somewhat ‘negative’ document – saying almost as much about what it ‘doesn’t want’ as it does about ‘what it does’ (banning new light industry seems exceptionally short-sighted). Also, the LS plan isn’t a ‘plan’ as such, it’s more a really a large collection of requirements bonded to some land use proposals. Calling it an urban design framework would be more appropriate than a ‘plan’ – though this is semantics.

Hindsight is clearly 20/20. One just has to look at recent population trends to declare a ‘neighborhood winner’ – LS was up +18% in 2010 from 2000 figures, JVL was down -14%. Part of this can be contributed to how the neighborhoods planned for their respective futures. However, to say that one plan was a success and the other a failure does a disservice to the other considerable issues at play. One cannot make judgment calls on the two plans and say one was better than the other – each could have been useful in the right context. In comparison of these plans though, it is clear to see the shortcomings of the JVL plan in comparison to the LS one.

JeffVanderLou Neighborhood Plan – City of St. Louis, MO – 2001

Lafayette Square Neighborhood Urban Plan – City of St. Louis, MO – 2001