This article originally appeared on the excellent St. Louis Energized blog where Ben explores the positive opportunities for a better St. Louis and often posts his incredible photos of the city.

In the wake of disappointing Census results released last week, many St. Louisans are calling for “new thinking” for the future of St. Louis. Some of these demands are pointed directly at the region's current political leadership, while some are coming from the leaders themselves. Calling the population drop in the City of St. Louis "absolutely bad news," Mayor Francis Slay proclaimed that "this will require an urgent and thorough rethinking of how we do almost everything."

It would be hard for any St. Louisan to disagree. The Census revealed a dismal rate of growth across the entire region (less than half the national rate), and a particularly troubling population loss in the region’s core.

It would be hard for any St. Louisan to disagree. The Census revealed a dismal rate of growth across the entire region (less than half the national rate), and a particularly troubling population loss in the region’s core.

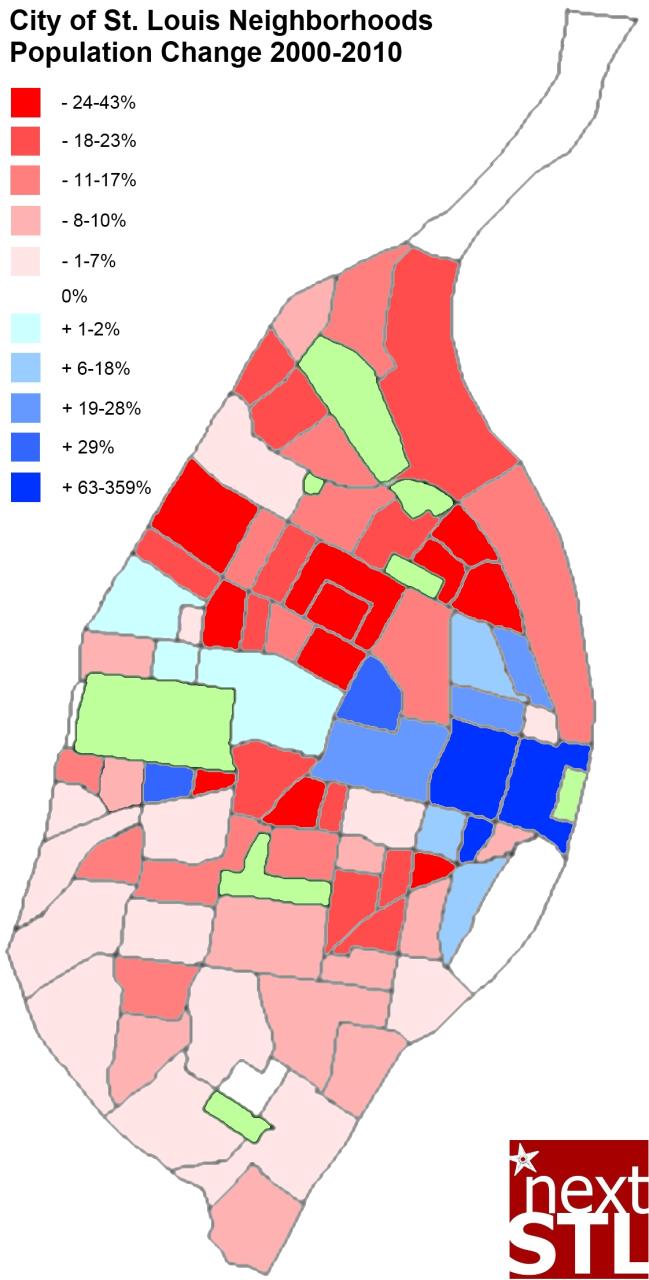

And in this instance, “core” does not mean downtown, the “inner city,” or even the entire City of St. Louis. In addition to the loss of 29,000 residents in the City (an 8% decrease), the much larger County of St. Louis also suffered a population loss of almost 2%. The Census results gave lie to any notion that a weakening urban core does not affect the surrounding suburbs, as the continuing exodus sends residents to ever-farther-flung areas.

New ideas clearly are necessary for the sake of the future of St. Louis. But what does “new thinking” look like? It depends, of course, on who you ask. Everyone promotes the things they happen to be thinking about, and there are widely-varying worldviews on where the region should go from here.

To me, “rethinking” and “new thinking” means—in a very general sense—at least two things. First, exploring and implementing fresh, bold, and risky ideas that directly confront the hardest-to-solve problems in the urban core. And second, finally moving forward on long-discussed ideas that have failed to move beyond talk to action, even though generally perceived as beneficial to the future of St. Louis as a region.

Exploring "New" Ideas

In the first category, two new efforts immediately come to mind. The first of these is Open/Closed: Exploring Vacant Land in Saint Louis, a two-day series of meetings organized by NextSTL and Frontier St. Louis. On March 18th and 19th, Open/Closed will explore solutions to the problem of the "thousands of vacant homes and lots that have a corrosive effect on our community."

In the first category, two new efforts immediately come to mind. The first of these is Open/Closed: Exploring Vacant Land in Saint Louis, a two-day series of meetings organized by NextSTL and Frontier St. Louis. On March 18th and 19th, Open/Closed will explore solutions to the problem of the "thousands of vacant homes and lots that have a corrosive effect on our community."

Open/Closed has scheduled an impressive line-up of panelists and speakers, including politicians and activists; representatives of the Show-Me Institute, the Great Rivers Greenway, and the Preservation Research Office; and Paul McKee of McEagle Properties and the controversial Northside Regeneration project.

(Interestingly, as of this posting, the City's Land Reutilization Authority has not indicated that it will send an LRA representative to Open/Closed, despite invitations. The LRA owns over 9,000 vacant parcels in the City, and serious questions have been raised about its refusal to sell City-owned parcels. Failure to participate in Open/Closed would seem to belie the City's commitment to a "rethinking of how we do almost everything.")

A second relatively new effort is The Brick Bank, which hopes to save bricks and other architectural elements from the numerous crumbling structures throughout the City. By collecting and securing the bricks (and, eventually, full-scale deconstruction of structures that are beyond repair), the Brick Bank hopes to make the bricks available for future construction and to stem the bleeding of red brick out of St. Louis caused by brick thieves.

A second relatively new effort is The Brick Bank, which hopes to save bricks and other architectural elements from the numerous crumbling structures throughout the City. By collecting and securing the bricks (and, eventually, full-scale deconstruction of structures that are beyond repair), the Brick Bank hopes to make the bricks available for future construction and to stem the bleeding of red brick out of St. Louis caused by brick thieves.

Granted, these are only two (somewhat related) efforts to identify solutions to the sea of problems that St. Louis needs to address. But they are big ideas, meant to address big problems, and worthy of serious consideration. Undoubtedly, some of the specific proposals coming out of these groups will be highly controversial, as would be expected with any radical rethinking of how to tackle St. Louis' most intractable problems (think: charter schools, and the NorthSide Regeneration project). But their organizers and advocates deserve credit for exploring solutions to difficult problems and should be engaged seriously by the City's current political leaders.

Implementing "Old" Ideas

The second category is not exactly "new" thinking, but rather the implementation of ideas that have been jawed over for years. As a region, it seems clear that St. Louis does not have a problem pinpointing some of the major issues holding it back. Taking concrete steps toward solving those problems appears to be more difficult.

The reunification of the City and the County is, in my view, one of the biggest issues in this category. Admittedly, many people (in both the City and the County) oppose the City's re-entry into the County, and it certainly isn't going to be a cure-all for the region's ailments. As I have written here and here, though, I believe that re-entry would increase regional cooperation and be an important step toward competing more against other regions than ourselves.

Thankfully, St. Louis is focusing more and more on the problems caused by the region's fragmentation, with the Census results prompting even louder calls for greater intra-regional cooperation. Citizens' groups have joined the cause, including the "St. Louis is a World Class City" group helmed by business owner Bill Frisella and Dr. Charles Schmitz of UMSL, which promotes re-entry. I hope their efforts at governmental restructuring are successful, but if not, that they at least catalyze increased collaboration and a reduction of wasteful redundancies throughout St. Louis.

Thankfully, St. Louis is focusing more and more on the problems caused by the region's fragmentation, with the Census results prompting even louder calls for greater intra-regional cooperation. Citizens' groups have joined the cause, including the "St. Louis is a World Class City" group helmed by business owner Bill Frisella and Dr. Charles Schmitz of UMSL, which promotes re-entry. I hope their efforts at governmental restructuring are successful, but if not, that they at least catalyze increased collaboration and a reduction of wasteful redundancies throughout St. Louis.

Another "old" idea that needs to move forward into action is a modification of the way in which public financing incentives—particularly tax increment financing—are used by intra-regional municipalities in an "inefficient, zero-sum competition for tax base with their neighbors." Public financing incentives can be powerful and legitimate development tools, but in their current form have failed to create economic growth in the region.

Two changes are particularly needed. One, TIF—an incentive that has "drifted" very far from its original purpose—should be made unavailable for retail projects. Although TIF can make sense for capturing property taxes that truly would not have been available "but for" the development, it seems indisputable that retail TIFs do nothing more than shift around a finite pool of retail activity and sales tax dollars. One town's "win" is another town's loss, with no net economic growth for the St. Louis region as a whole.

Two, public financing should be directed toward where it is truly needed the most. In my view, that means primarily focusing on truly blighted areas of the urban core, that have little or no chance of a major rebirth without significant investment by both the private and public sectors. That might mean a further tightening of the definition of "blight" required for TIF projects, and other measures ensuring that incentives like New Markets Tax Credits are directed to areas that need them the most. (On the latter note, Wednesday's announcement that Peabody Energy turned down $10 million in NMTCs was a breath of fresh air, whatever the motivation behind the decision might have been.)

Governmental consolidation and public financing reform are only two examples of regional issues that, if turned from mere ideas into action, might go a long way toward improving regional cohesion and St. Louis' economic future. Of course, there are other impediments to regional growth, including macroeconomic issues such as attracting jobs to the region. All of these regional problems are incredibly complex issues that require focused attention by the business community and our political leadership (regionally and state-wide). They are not, however, unsolvable—at least if the region begins moving from thinking to acting, starting today.

(As somewhat of a sidenote, I would argue that there is a third category of "thinking" that deserves our close attention:protecting ideas that have already proven to be highly successful, from short-sighted attacks and harmful changes. I would place Missouri's historic tax credit program—which I have written about here, here, here, and here, and the fate of which is still uknown—at the top of this category of proven-to-be-correct thinking that should be modified as little as possible. And I do believe that principled distinctions can be made between HTCs and other less efficient and more abused tax incentives, but that is a topic for another day.)

(As somewhat of a sidenote, I would argue that there is a third category of "thinking" that deserves our close attention:protecting ideas that have already proven to be highly successful, from short-sighted attacks and harmful changes. I would place Missouri's historic tax credit program—which I have written about here, here, here, and here, and the fate of which is still uknown—at the top of this category of proven-to-be-correct thinking that should be modified as little as possible. And I do believe that principled distinctions can be made between HTCs and other less efficient and more abused tax incentives, but that is a topic for another day.)

Strengthening the Core for the "Urban Birds"

Perhaps not surprisingly, the new ideas discussed above tend to be ones that directly impact the urban core. The City, particularly hard-hit areas like north City, requires our most focused attention and boldest ideas if we ever are to reverse the hollowing out of St. Louis.

At their core, these are ideas about making urban communities more livable for the residents and workers who are already there—places that offer a good quality of life as measured by safety, attractive streetscapes and structures, community cohesion, walkability and accessibility, recreational opportunities, and human-scaled improvements. It's not an "if you build it, they will come" mentality (which hasn't worked for St. Louis), but making an area more livable for the current population does result in an environment to which others are more likely to gravitate.

Whenever I think about livability, the phenomenon of niche differentiation comes to mind. Niche differentiation is a process of natural selection where competing species partition resources and adopt different habitats so as not to out-compete each other. For example, two bird species might feed at different heights of the same tree, or have specialized beaks adapted for particular food sources.

Whenever I think about livability, the phenomenon of niche differentiation comes to mind. Niche differentiation is a process of natural selection where competing species partition resources and adopt different habitats so as not to out-compete each other. For example, two bird species might feed at different heights of the same tree, or have specialized beaks adapted for particular food sources.

In terms of human populations (e.g., St. Louis residents), I think of niche differentiation less in terms of competition, and more in terms of the natural inclinations people have toward living in particular types of environments. Many people thrive on cities and everything that comes with them—density of population and development, walkable communities, and the vibrancy of mixed-use/mixed-income neighborhoods. I think of this group as the "urban birds."

Others simply don't share those values, or place higher value on the positive attributes of outlying areas (e.g., better public schools) than what they value about the city. And generally speaking, there is nothing wrong with that—different strokes for different folks, as they say (and contrary to the theories of some urbanists, the suburbs aren't going anywhere anytime soon). Of course, St. Louis (like all regions) should work against sprawl and toward smarter growth, but it's fanciful to think that the majority of the region is going to be converted to urban living.

In the absence of acceptable urban "habitats," though, even those highly inclined toward city-dwelling are forced to "adapt" to different environments. At least in the near-term, this might directly benefit the areas to which these urban birds fly (e.g., St. Charles, Warren, and Lincoln Counties, each of which enjoyed a significant population increase over the last decade). But on a long-term, regional basis (which is the way I think St. Louis must consider these issues), it is to our collective disadvantage not to have a healthy City environment capable of attracting urban-minded people from other regions. A vibrant urban core is absolutely essential to the long-term prosperity of any metropolitan area.

In some City neighborhoods, improvements in livability have resulted in growth. Downtown's population, for example, increased 359% from 2000 to 2010, in the face of significant population loss in the City overall. Downtown's renaissance is directly attributable to improvements in livability, including restored historic buildings, attractive residential options (e.g., the Washington Avenue Loft District), increases in safety, improved streetscapes, and new recreational options (e.g., Citygarden). As a result, downtown St. Louis has become a place where urban birds want to, and do, live.

In some City neighborhoods, improvements in livability have resulted in growth. Downtown's population, for example, increased 359% from 2000 to 2010, in the face of significant population loss in the City overall. Downtown's renaissance is directly attributable to improvements in livability, including restored historic buildings, attractive residential options (e.g., the Washington Avenue Loft District), increases in safety, improved streetscapes, and new recreational options (e.g., Citygarden). As a result, downtown St. Louis has become a place where urban birds want to, and do, live.

On the other hand, population has decreased in some neighborhoods despite what, by most accounts, would be considered to be significant improvements in livability. On the City's near south side, for example, neighborhoods such as Tower Grove East, Shaw, and Fox Park saw significant "pop drops" even while "acquiring the trappings of urban revitalization." In these neighborhoods, population growth is either merely lagging improvements in livability (at best), or is held back by other overriding, negative dynamics despite such improvements (at worst).

So what conclusions can we draw? For one, there obviously are negative dynamics that will continue to preclude growth in the City irrespective of improvements in livability made to this or that neighborhood. Most obviously, the City will continue to lose families in the absence of quality, affordable school choices. Charter schools, while controversial, are certain to be instrumental in reversing the flow of families out of the City. (Jeff Rainford, Chief of Staff to Mayor Slay, recently noted on Twitter that "[i]f not for charters, the City would have lost at least another 15,000 people.").

Perhaps as importantly, growing the urban core will ever be an uphill battle so long as we are not briskly adding to the population of the region as a whole. Population growth (or even stabilization) in the City can only be achieved by stemming the outflow of current residents and by capturing a reasonable percentage of new residents that are moving into the region at a faster-than-current rate.

Last year, Aaron Renn, an urban analyst writing as The Urbanophile, laid out a "10 percent solution for urban growth" in Rustbelt-type cities (also discussed here). The "10% solution" simply means that a region such as St. Louis should "seek to capture about 10% of net new regional growth for the urban core." While seemingly unambitious, Renn makes a case for the 10% solution being not only achievable, but "utterly transformative."

Last year, Aaron Renn, an urban analyst writing as The Urbanophile, laid out a "10 percent solution for urban growth" in Rustbelt-type cities (also discussed here). The "10% solution" simply means that a region such as St. Louis should "seek to capture about 10% of net new regional growth for the urban core." While seemingly unambitious, Renn makes a case for the 10% solution being not only achievable, but "utterly transformative."

But what about in a region like St. Louis where overall population growth is abysmal? Unless our overall region begins growing at least at an average rate, and a meaningful percentage of new residents are attracted to the core, it will be difficult to achieve a critical mass of City (or even County) residents to turn around the population losses of the past. As Renn states:

Obviously [the 10% solution] only works if your region is growing. If you are stagnant or shrinking, you've got a bigger challenge on your hands. There the imperative is to restart the regional economic and demographic engine. Hopefully the core can play a role in doing that.

Strengthening the Region for All St. Louisans

So how does St. Louis strengthen the region as a whole? We could start by actually implementing some of the "old" ideas discussed above, rather than just talking about them. We also should vigorously pursue the modest-but-measurable goals set forth in the Regional Chamber and Growth Association's latest five-year plan, which calls for St. Louis "to rank consistently in the top half of the nation's big metro areas on various economic measures." Successfully implementing the RCGA's plan to achieve its goals (primarily through measures to attract workers and entrepreneurs) will require concerted efforts at the municipal, county, and state-wide levels.

But Renn is surely correct that the urban core will have a role in "restart[ing] the regional economic and demographic engine" of St. Louis, and a key one at that. The nation-wide trend lines are clear: an ever-growing number of residents (and even businesses) value centrally-located, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. Whether or not the bulk of our region's current residents want to live in or near the City, we cannot hope to attract these future generations of urban birds without a strong core. For me, this is not a "city v. suburbs" mentality; if we can successfully shape the City to bring more residents and businesses to "St. Louis", it ultimately will benefit all of the region, not just the City itself.

Interestingly but not surprisingly, then, St. Louis faces the same chicken-and-egg problem facing other Rustbelt cities. Without a healthy urban core, it is difficult to grow the entire region by attracting the next generation of residents and businesses; healing the core, in turn, is an uphill battle unless the region as a whole is strong and growing. The future of St. Louis depends on an interdependent and symbiotic relationship between the City and the rest of the region, and strengthening St. Louis as a whole requires focused attention on both.

A Call to Action

"Rethinking" or "new thinking" for St. Louis' future can mean different things, then, depending on the issue being addressed. People will, and should, disagree about what ideas are more or less worthy of our collective attention. It seems clear, though, that identifying ways to make our urban core more livable and implementing ideas to grow the region as a whole are equally important.

What is even more critical is that St. Louisans move beyond just "thinking" about these issues, and begin doing. It will be difficult to reverse the downward trend of the past decades, but, with sustained action, not impossible. Key efforts are already underway.

In my view, a critical component of turning big ideas into future-changing actions is close cooperation among different "factions" of St. Louisans—the City, County, and other regional entities; Republicans and Democrats; different races and ethnicities, particularly the black and white communities; the public and private sectors; and the so-called "old guard" and the "new guard" of community and political leaders.

In my view, a critical component of turning big ideas into future-changing actions is close cooperation among different "factions" of St. Louisans—the City, County, and other regional entities; Republicans and Democrats; different races and ethnicities, particularly the black and white communities; the public and private sectors; and the so-called "old guard" and the "new guard" of community and political leaders.

On that last item, I'm certain that some disagree, preferring instead a "revolution" against the perceived failures of current leadership and a "now we're going to do it my way" mentality. It is not difficult to understand; for those who have long worked hard to make St. Louis a better place, the Census results were crushingly disappointing and frustrating.

But if the Census has taught us anything, it's that we—all St. Louisans—are in this together. I believe that it is incumbent on our "old guard" leaders (political and otherwise) to engage seriously with the "new guard" thought leaders of St. Louis in determining our future direction, and that the "new" must engage the "old" to maximize the likelihood of success of their efforts. Now is the time for work, and if people remain unsatisfied with the direction our region is headed—well, as the President has been known to say, "that's what elections are for."

If all of this talk of "inter-faction cooperation" sounds Pollyannish, consider that St. Louis has recently shown the ability to come together on other vital efforts, including the passage by County voters of a sales tax hike for public transit (a cause more typically championed in the urban core), and the (unfortunately unsuccessful) effort to land the 2012 Democratic National Convention, generally supported by Democrats and Republicans alike.

If St. Louis does not face an existential threat per se, it at least stands at a crossroads of the very nature of what "St. Louis" will mean to residents and the world at large in the future. The Census has given us an enormous wake-up call, and surely can spur other cooperative efforts among unlikely bedfellows. As Mayor Slay said, "[i]f this doesn’t jump-start regional thinking, nothing will."

Consider also that we surely won't succeed in rebuilding the City and our region without the active participation of many, many St. Louisans. No white knight is coming to save us; it is up to us. Every person who professes to care about St. Louis must get actively involved in shaping its future.

Consider also that we surely won't succeed in rebuilding the City and our region without the active participation of many, many St. Louisans. No white knight is coming to save us; it is up to us. Every person who professes to care about St. Louis must get actively involved in shaping its future.

That might seen daunting, as it's easy to question how much impact any one person can really have. But often it just involves taking a first step—researching an issue, making a call, asking how you can help. Consider: What issues are you passionate about? What skills can you offer? Who, or what, do you want to help?

I, for one, love St. Louis as it is. So I will continue to enjoy, promote, and boost St. Louis, and hope others do the same. We should be proud of a City (and region) of such rich history, beautiful architecture, diverse neighborhoods, and friendly people. Like many others, though, I recognize our vastly under-realized potential. My commitment is to stay involved and engaged in various efforts to help reach that potential over the upcoming years and decades.

What are you going to do to help create a better future for St. Louis, today?

It would be hard for any St. Louisan to disagree. The Census revealed a dismal rate of growth across the entire region (less than half the national rate), and a

It would be hard for any St. Louisan to disagree. The Census revealed a dismal rate of growth across the entire region (less than half the national rate), and a