{rendering of a courtyard at De Tonty Commons – UIC proposal}

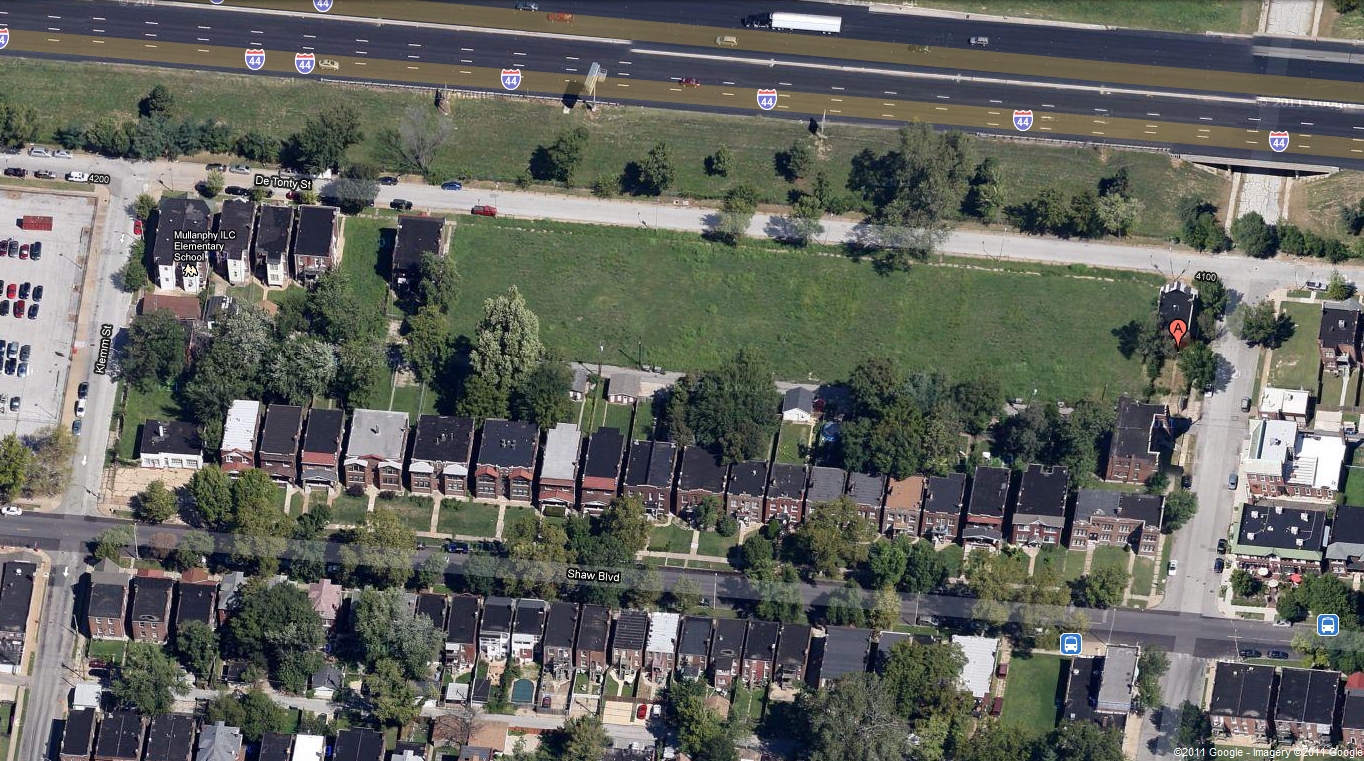

The 4100 block of De Tonty Street in the City of St. Louis Shaw neighborhood has been vacant for more than a decade. Fourteen lots are empty, cleared in fits and starts beginning in 1998 with the demolition of a four-family building. Two more demos came in 1999, two in 2000, four in 2002 and the final two in 2007. The city’s Land Reutilization Authority (LRA) now owns all 14. In all, at least forty residential units once occupied the site.

One week ago, UIC, the architecture and design firm whose vision has unexpectedly transformed a forgotten in-between city neighborhood into a model for redevelopment, presented the city’s Cultural Resources Office with a plan for De Tonty. The plan calls for 16 single-family homes oriented toward two courtyards and away from De Tonty and the abutting Interstate 44. If the history, market and I-44 weren’t enough of a challenge, the site sits within the Shaw Historic District. And this is where things get interesting.

While neighborhoods can be designated historic at the federal and state level, it’s the local historic district that affords the most control, is the most prescriptive. Implemented and approved by a district's residents, local historic district regulations can only be amended by residents. Land-use decisions reside at the local level and everything from the aspect ratio of windows to building setback to chimney height can be prescribed. The purpose is to preserve the historic aesthetic in each and every contributing structure, new or old.

{De Tonty Commons site plan – UIC proposal}

{aerial view of 4100 De Tonty}

Of 11 points considered by the CRO regarding the UIC De Tonty proposal, it determined the project complied with just three; those pertaining the landscaping, other ground cover and parking. Three were inconclusive and five considered “Does not comply”. With significant community support, a development can go to the city’s Preservation Board to appeal a CRO denial, and perhaps prevail. Often, non-compliant elements can be tweaked, or modified to comply.

Looking at individual criteria in this case, begins to illustrate the limitations of the existing Shaw Historic District code:

A. Height: New buildings or altered existing buildings, including all appurtenances, must be

Constructed within 15% of the average height of existing residential buildings on the block.

Does not comply. The remaining buildings on the block are two stories.

Here the block consists of six buildings and 15 vacant lots. It appears that the proposed construction is likely just less than within 15% of the average height of existing buildings.

B. Location:

Location and spacing of new buildings should be consistent with existing patterns on the block. Width of new buildings should be consistent with existing buildings. New buildings should be positioned to conform to the existing uniform set back.

Does not comply. While along De Tonty there is a variety of residential building types ― one‐, two‐ and four‐family buildings ― all are sited to face the street and conform to a consistent setback. The proposed development will create two “courts” perpendicular to De Tonty, each with 8 houses facing an interior walk.

The CRO evaluation recognizes the precedent within Shaw of residential courts (Hortus Court probably being the most similar), but concludes that existing examples are much deeper, and do not present all homes to a street view, as does the proposed development.

{the De Tonty Street site today}

The recommendation goes on to explain that De Tonty Commons wouldn’t comply with Shaw Historic District regulations for exterior materials (it needs to all be brick), architectural detail (the proposal doesn’t replicate details already present), and roof shape (the dominant type is flat). Others have envisioned infill that would likely pass CRO muster, including this proposal from What Should Be on nextSTL. LRA ownership means, in effect, that whatever is built will require the approval of 8th Ward Alderman Stephen Conway and the Missouri Botanical Garden, just a few blocks away. The city will not approve a development plan opposed by either. The CRO recommendation is just step one in the development process and it's anticipated that UIC will present the development for review again and work with residents and city representatives to address concerns.

{profile of De Tonty Commons home – UIC}

Here, the issues seem larger than the pitch of the roof. Local historic district regulations serve a purpose; to preserve the historic integrity of a neighborhood, district, or portion of a city. This is what prevents Home Depot doors on Soulard homes and cinder block retaining walls in Benton Park. This tells a homeowner than an investment in their historic home won’t be deadened by a neighbor’s chain link fence or ill-fitted white vinyl windows. And local historic districts have been found to enhance property values.

So what’s not to like? For the heart of historic districts, little. In fact, preservation districts evolved from the recognition that a single historic landmark deserves to retain its context. Virtually no one would like to see contemporary infill sandwiched between a couple 1895 Victorians facing Lafayette Square Park, though it’s debatable whether or not historic district guidelines there have produced anything more than noticeably off-kilter facsimiles of their historic neighbors.

{historic district regulations in Lafayette Square have produced attractive, but fake historic infill}

{a previous more traditional infill proposal for 4100 De Tonty has long since disappeared}

If the De Tonty site were at Cleveland and Lawrence, the heart of Shaw, the discussion would be different. However, along its entire length it faces a 15-foot Interstate embankment. Is it reasonable to require the same exacting standard as new infill on Flora Place? Whether or not one fully endorses the existing UIC proposal, the limitations of our existing development framework is acutely antiquated. The existing UIC proposal has likely already been limited and contorted in an attempt to conform as much as possible to historic district guidelines. What would be possible if the visioning process was more open for public considering?

A basic proposal: local historic districts should be regulated by gradation. Back to Lafayette Square: it serves neither the local historic district, nor the immediate surrounding neighborhoods to have drastic shifts in building regulation across a city street. Historic district regulation should move from strict at a district’s defining core or places, toward a form-based code at the edges. This would do more to preserve an historic district than current regulations as it would preserve a feeling of place by graying the line between the regulated historic district and a free-for-all.

Imagine a Lafayette Square that invites reinterpretations of Victorian homes (new materials used on the same basic building envelope for instance) on streets such as Dolman or Chouteau at the district’s edge. Imagine single-story homes, vinyl siding and certain commercial developments not being allowed across the street from where now it’s required to build to particular exacting standards.

In Shaw this would mean recognizing the challenges facing the De Tonty site. In general, facing the Interstate is not something a homebuyer would value. Why force new development to do so when the highway’s intrusion is clearly a massive hindrance, and one that existing century-old homes obviously did not have to consider? How can any development code refuse to acknowledge the existence of an urban Interstate?

Any city needs housing options. The City of St. Louis needs more than most. Our greatest asset may be our historic building stock, but it’s also acts as a hindrance to attracting new residents. When historic district regulations clearly prescribe an unnatural solution to a decade old complex land-use issue, those regulations should be reevaluated and reconsidered. Historic districts and preservation must evolve from freezing time to creating better cities that fit existing context. Residents of St. Louis local historic districts should reevaluate the limitations imposed by current regulations. The thick solid lines demarcating historic from non should be blurred. Better historic districts and a better St. Louis would result.

De Tonty Commons – St. Louis City Cultural Resources Office Submittal – July 10, 2013 by nextSTL.com

Shaw Neighborhoood Historic District Standards – St. Louis, MO by nextSTL.com

City of St. Louis Preservation Board Agenda July 22 2013 by nextSTL.com

Press Release: UIC Announces DeTonty Commons Project in Shaw Neighborhood by nextSTL.com