The Pruitt-Igoe Myth: An Urban History is an incredible film. It doesn’t answer a single question about the failure of Pruitt-Igoe.

The Pruitt-Igoe Myth: An Urban History is an incredible film. It doesn’t answer a single question about the failure of Pruitt-Igoe.

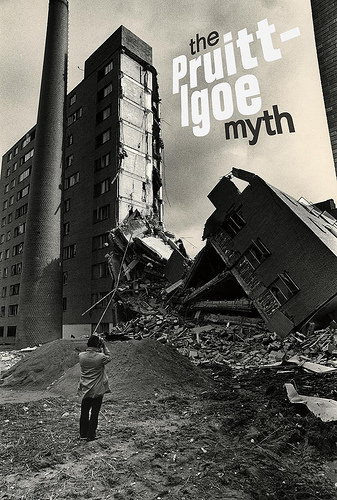

Maybe that’s why the film is so engrossing. The film sets out to defy conventional wisdom, to refute long-held beliefs, the myths built to define, and absolve us of, the public housing project’s demise: the high rise architecture was to blame, the residents were immoral and didn’t care for their homes, the free market better provides housing for the poor. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth succeeds by not simplifying what is plainly the story of the American city. You leave only understanding that the story of Pruitt-Igoe is more complicated, more personal than you thought before you entered.

While a clear answer may not be offered, a story of unmistakable clarity emerges. Pruitt-Igoe is St. Louis. St. Louis is Pruitt-Igoe. The public housing project failed as the city failed. Built for a post-war St. Louis of 1M people, fewer than 500,000 residents remained as the last of 33 buildings was demolished in 1977. The first tower to be razed was imploded in 1972. In this way, Pruitt-Igoe itself is the screen on which we can view our city’s history.

A full house was on hand last night at the Tivoli Theater to view the film’s second St. Louis screening. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth has been praised at film festivals across the U.S., earning Best Feature Documentary awards at both the Oxford and the Kansas City Film Festivals. Additional screenings are being added regularly and International screenings will soon be scheduled for this fall. Check the film’s website for future screenings.

The film is largely a narrative of life at Pruitt-Igoe as told by former residents. Context of the larger city and nation are added by a narrator. The use of extensive archival film and photos and juxtaposition of varied personal experiences keep the narrative building and the emotions of the viewer swaying from the life affirming experience of growing up in a vibrant community to the hell of living with drugs, murder and fear as a child.

When I feel bad, I don’t mean to, but I dream of Pruitt-Igoe. I often wonder if I would have been a nicer person today if I hadn’t lived in Pruitt-Igoe. Both are statements from individuals who lived in Pruitt-Igoe. Reaching a of peak of about 11,000 residents, Pruitt-Igoe was a city within a city. The experience of living there was just as varied as those living elsewhere. There were beautiful moments and terrifying tragedies. In between was a generally hard life. And all the while, the larger city and nation was to dictate the community’s future.

This future was substantially the same as the rest of St. Louis. Living in Pruitt-Igoe or not, the urban poor were displaced and displaced again in the second half of the 20th Century. So called “Urban Renewal” projects pushed African American communities further and further from central cities, just ahead of the bulldozer. In St. Louis, first the central riverfront was cleared, then Chinatown, then the Mill Creek Valley and other communities.

The city was in free fall. Tens of thousands of residents were fleeing across the County line seeking homogenous suburban communities, largely enabled by the 1949 Housing Act. Yes, the film recognizes that welfare policy, federal funding guidelines and more contributed to failure, but within this political and social context, Pruitt-Igoe had to fail. Individual apartment buildings and tenements were failing across the city. If the rest of the city were able to have been removed with several hundred charges of explosives, I have no doubt it would have. But they weren’t has big as Pruitt-Igoe. The demolition of a block of row houses could not be captured in the dramatic fashion of a high rise implosion. And Pruitt-Igoe was billed as the solution to the slums. For the first time, the poor were no longer going to be moved from slum to slum, but from slum to light filled, modern high rise.

Without a doubt, living conditions in post-war St. Louis were unsafe and unhealthy. This is where the movie starts. Pruitt-Igoe was the answer to a very real and very serious problem. As the film states, families who lived in basements, never having the sun reach their living quarters, families who lacked indoor plumbing, now lived with modern amenities, private bedrooms and natural sunlight. Many residents of Pruitt-Igoe had a better view from their apartment than the wealthiest people of St. Louis.

An answer to current conditions was needed, private enterprise had clearly failed to house the poor, and Pruitt-Igoe was offered as the solution. By accounts in the film, the first years of the development were good ones. Buildings were maintained, security patrolled the grounds and residents were black and white and mixed-income. Then the project was desegregated in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the same year the first residents moved in. White families fled. Middle-class families fled. Again, mirroring the larger city. Tenant rent revenue, declined. The buildings were no longer maintained. The city surrounding Pruitt-Igoe was being abandoned and demolished.

As Pruitt-Igoe failed, glorious public monuments rose within eyesight. Pruitt-Igoe residents Sylvester Brown, Jr. and Valerie Sills, as well as film Director Chad Freidrichs, answered questions and added perspective following the film. An audience member stated that the appearance of the St. Louis Arch in many images helped give him ownership of Pruitt-Igoe and the city’s history. The mention of the Arch touched off other comments.

The single most iconic image of Pruitt-Igoe is the implosion of a tower with the gleaming Arch in the background, two miles distant. Ms. Sills recounted that as a student she signed the time-capsule placed in the monument’s keystone. In her Pruitt-Igoe apartment she wondered how a city could build something so beautiful while treating its people so poorly: “It serves no purpose. We built a monument to nothing.” The Arch was completed in 1965 as the housing project descended into decay. Freidrichs noted that the proximity of the two public projects gives weight to the story that would otherwise being missing. Today, a $578M effort is underway to revitalize the Arch grounds.

The film shows Pruitt-Igoe as a community, its residents as people. The sounds of a record player pushed to a doorway to be heard by an entire floor, the smells of a dozen different dinners being prepared, the hundreds of sets of Christmas lights reflected in the snow; these are the cherished memories of childhood. The fights, the drugs and crime were life for many in the city.

The film shows Pruitt-Igoe as a community, its residents as people. The sounds of a record player pushed to a doorway to be heard by an entire floor, the smells of a dozen different dinners being prepared, the hundreds of sets of Christmas lights reflected in the snow; these are the cherished memories of childhood. The fights, the drugs and crime were life for many in the city.

If the film’s message is that Pruitt-Igoe is St. Louis, we’re left to wonder what the hell happened to our city? If the residents of Pruitt-Igoe were people just as others in the city, what does that say about how we treat the poor? We’re rewarded today by the fact that Pruitt-Igoe was large enough and dramatic enough to receive a spotlight. As a mirror, it tells the story of St. Louis as nothing else can. In the honest and balanced hands of Freidrichs and Producers Paul Fehler, Jamie Freidrichs and Brian Woodman, the lazy and damaging myths of Pruitt-Igoe are easily dispelled, replaced with a clear presentation of the true complexity of our urban history. What more could one ask?

Additional nextSTL coverage of Pruitt-Igoe, urban renewal and The Pruitt-Igoe Myth:

nextSTL Preview: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth: An Urban History

[Open/Closed] Pruitt-Igoe Bee Sanctuary presentation by Juan William Chavez

Colin Gordon Talks Mapping Decline, Vacant Land and Urban Renewal with nextSTL

{all images courtesy of pruitt-igoe.com}