{a view of what I-755 might have looked like when complete; Booker Incorporated Engineers, Architect & Planners. “Analysis of Selected Engineering and Environmental Factors, Route 755.” City of St. Louis, 1979.; map courtesy of Google Maps; image by author}

The City of Saint Louis… and the Missouri State Highway Department… have long recognized Route 755 as a key part of the transportation plan necessary for the revitalization of the City. Construction of the freeway… will relieve serious traffic flow restrictions at the present interchange of I-44 and I-55, on north-south City arterials, on residential streets, and I-70—I-55 downtown. The existing freeway system was designed with Route 755 as in integral part of the overall system to handle the area’s anticipated future traffic growth. Without this vital link, the entire system is inadequate and cannot function as planned.[1]

Hidden in the downtown St. Louis landscape are subtle hints of a history that did not come to pass.

Grandiose ramps leading to unassuming streets off of Interstates 64 and 44 are the only physical presence of another expressway which was never built. Route 755, or the North-South Distributor, as it would generally be known, was part of a massive arterial system for the City and one of the few parts that was not completed.

It would have connected the City’s four major Interstates and provided an expressway route across the center of the City. But on its rocky path to fruition, it encountered a furious swarm of complications that would ultimately keep it from ever seeing construction. Public outcry, galvanized after seeing the adverse affects of earlier highways, took on a new and more powerful role in opposing the Distributor, and may have seen new, more effective tactics employed against the arterial expansion. Funding issues also served to derail the project, as did a cultural shift in how our nation views its major roadways. The North-South Distributor, the City’s massive unbuilt civic project, has within its history much of the story of the American roadway, and its failure remains—perhaps now more than ever—an important lesson.

As the nation ushered in the wartime 1940s, so too did it the era of the expressway and arterial expansion. In St. Louis, perhaps the first public mention of such expansion came in 1943, when the Post-Dispatch published a brief article detailing the planning of three “superhighways”, in the amount of forty four total miles—eleven of them elevated—to be managed by the Missouri State Highway Department and funded jointly by the State and Federal monies of around $100 million.[2]

A few years later, Harland Bartholomew, the Chief Planning Commissioner of the City since 1917, made his most well-known impact on the City of St. Louis with the Comprehensive City Plan of 1947. This plan, among many other visions for the City, outlined an aggressive plan for the widening of many City streets and the implementation of a system of major expressways throughout the City. This would become the ultimate template for arterial development in the City for decades to come.

{Bartholomew, Harland. “Comprehensive City Plan: Saint Louis, Missouri.” City Planning Commission, 1947. Plate No. Twenty.}

Bartholomew’s Plan was more developed than the three highways predicted in 1943, including a major artery running close to the River from the South to the North of the City limits. From downtown, an additional three expressways radiated toward City limits to the West, following roughly along Gravois, Chouteau and Natural Bridge Avenues. Finally, these routes were bisected by three North-South distribution expressways, roughly at 18th Street, Morgan Ford Road/Boyle Avenue/Whittier Street and McCausland Avenue/Skinker Boulevard/Hamilton Avenue. The plan additionally called for additional arteries beyond the City limits both in St. Louis County and in St. Clair County in Illinois across the River.[3] Improvements to the arterial system were a major focus in the report, as they had been for some time. Eldridge Lovelace notes that “most of the 1923 bond issue of St. Louis was for the improvement of the major street system.”[4]

The Bartholomew Plan called for a systematic overhaul and expansion of the City and area roads, and introduced the idea of both express and Federal highways into the City plan. The Plan states, “Federal funds will be available for improvement of certain major streets which provide access between the interstate highways and all principal sections of the city. These ‘Urban Distributing Routes’ may be either surface streets or they may eventually be separated grade expressways when the volume of traffic using them becomes sufficiently great.”[5] Included among these was a north-south route along the approximate path of 18th Street, which would be the first gestural precursor to the Distributor.

The Bartholomew Plan was shortly followed by a more detailed proposal for highway development in the City. The Expressway Plan for the Saint Louis and Adjacent Missouri Area, announced in 1951, was the product of several years of significant traffic studies, need assessments and highway plans.[6] This plan, conversationally known as the Elliott Plan after director Colonel Malcolm Elliott of the Missouri Highway Commission, represented the most direct look at the arterial expansion aspects of the Bartholomew Plan and would both catalyze and shape the subsequent highway development in the City.[7]

{Elliott Plan; Courtesy of Burbridge, J. “The Veering Path of Progress; Politics, Race, and Consensus in the North St. Louis Mark Twain Expressway Fight, 1950-1956.” Masters thesis, Saint Louis University, 2009.}

The Elliott Plan outlined the routes for three major radial arteries from the City Center, largely in line with previous plans but in greater detail. To the North stretched the Mark Twain Expressway which would run past Lambert airfield and along the Missouri River to the northwest. This route, which was modified in several places before its construction, is now U.S. Interstate 70. A second route, known as the Daniel Boone Expressway, spread westward, replacing sections of the smaller, existing Highway 40 and ultimately later taking the name Highway 40, now also known as Interstate 64. The third route ran south along the Mississippi River and was called the Ozark Expressway. This route is now known as Interstate 55, and Joshua Burbridge points outs that it is often erroneously believed that this route become Interstate 44, a route that was in fact added after the Elliott Plan.[8]

{“Progress Report on Area Road Building.” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 9.}

The Bartholomew Plan and Elliott Plan called for an extensive system of expressways and Federal Highways, and construction of these roads took many years. By the end of 1968, construction on the three primary expressways was nearing completion. Within the City limits, Highway 44 was the only of the three not yet fully open.[9] The Distributor was, by design, to be among the last of the major expressways to be built, and its construction was not put into serious planning consideration until 1969, when all the major highways now known as Interstates 64, 44, 55 and 70 were completed. Following the decision in 1972 to propose a complete length of the Distributor from I-44 to I-70, as approximated in the Bartholomew Plan, the Distributor received the official distinction State Highway 755.[10]

In anticipation of the construction of the Distributor, ramps had been built on Interstate 44 and Highway 40 to accommodate the connection to the expressway. The connection to Interstate 70 was also amended in preparation for the Distributor. These oversized ramps, palimpsest of a history that never happened, are still visible anomalies in the City fabric.

[slideshow_deploy id=’191813′]

The Distributor was first added to the official State System of Highways by the State Highway Commission in November of 1958. By March of the following year, following an initial public hearing in January, the Bureau of Public Roads had produced the first detailed map of the expressway.[11]

Pubic resistance to the North-South Distributor began in earnest when the project became a reality in 1969, following an agreement between the City and the State Highway Commission.[12] A public hearing on the expressway design in August 1970 saw twenty five of the thirty-one participants in vehement opposition to the plan, particularly with regard to a proposed extension north of Cole Street to the Mark Twain Expressway, enough disapproval to warrant the Federal Highway Administration to undertake an additional study and report on design changes to the expressway.[13] Mayor Alfonso Cervantes refused to allow the development of the expressway north of Cole Street, citing unreasonable disruption of residential areas.[14]

It seemed that more carefully voiced protest from residents in North St. Louis had succeeded in protecting their neighborhood where they had failed against the Mark Twain Expressway years earlier, foiled by a lack of organization and State maneuvers which placed proceedings and meetings in Jefferson City where the relatively immobile resident base of North St. Louis was unable to mount an effective protest.[15] But Mayor Cervantes would reverse his decision within two years.[16] It would take more than straightforward citizen protest to stop the highway.

The push for the expressway continuing, citizen groups may have taken new courses of action that had not been previously seen in the City. In 1971, under recommendation from the State Park Board, the National Register for Historic Places put the area surrounding Lafayette Park, a portion through which the Distributor was to pass, under historic designation.[17] The effect of this designation was staggering: while not protecting the area outright, now any project running through the designated area would be enjoined from receiving any Federal funding. It was largely understood that this effectively would kill the expressway project barring a route adjustment.

The effectiveness of this designation was clear. What remains less clear is the role preservationists did or did not have in getting the area listed on the Register. The Lafayette Park Restoration Committee repeatedly denied having any involvement in the decision to make the area historic, despite the understanding that the designation clearly served their interests of preservation.[18] Curiously, the move by the National Register quickly resulted in a swing of public opinion against preservation groups, which were suddenly forced to disassociate themselves from the Register and argue that they were not blindly against the expressway if certain conditions were met.

The State, which was expecting the Federal Government to meet up to fifty percent of the project costs before the designation, now lacked the funds to complete the project. Additionally, many residents of the neighborhood were enraged at the implications of the neighborhood’s new protected designation. The Saint Louis Globe-Democrat wrote, “angry homeowners of the Lafayette Park area, who have been waiting 10 to 15 years for action on the highway, said their property values are going down because of indecision about whether a highway will be built.”[19] The Saint Louis Post-Dispatch earlier noted in 1972, “the long delay [in building the Distributor] has caused the neighborhood to deteriorate.”[20] Many homeowners were speculating on the City buying their property from them for the use of the expressway; now property values were plummeting as the threat of development dissuaded new buyers from purchasing homes.

There is a logical basis to these complaints. It is clearly indicated that there was resident frustration over the delay of the expressway. Residents would have been expecting the State or City to reimburse them for the value of the homes that would soon be leveled to construct the expressway. Further, they would have had very little ability to sell their own homes on the market, as the threat of road construction would have convinced any savvy buyer to avoid that market beginning as early as 1947, when the Bartholomew Plan was issued. When the area was officially designated under the National Register, some residents may have been waiting over twenty years to have their homes acquired and reimbursed. Still more frustrating to many homeowners was the new concern of making improvements to their homes to the specifications of historical preservationists, a burden many argued would cost them significant additional money in home upkeep.[21]

Suddenly, preservationists were fighting a two-front war, against both City and State interests, angry at suspicions that the groups had gone “over the heads of local and state officials” to get Federal historic protection, and against a sizeable percentage of area residents who resented the impedance to their ability to cash out on their undesirable homes.[22] But the designation of the area was nonetheless sufficient to halt progress on the expressway without route alteration, regardless of the degree to which local preservationist groups may have actually been involved in the events leading up to Federal intervention.

Preservationist groups took special interest in a specific stretch of row houses known as the Harris Row, which lay on 18th Street south of Chouteau Avenue and directly in the path of the planned expressway. A City Hall meeting in February of 1973 attempted to make a compromise that would save the expressway. Among the suggestions were the relocation of the buildings on the Harris Row and the alteration of the route of the expressway to avoid them. Residents of the Harris Row, however, were hardly taken by the idea of their homes being relocated.

Similarly, Robert Hunter, the chief engineer for the highway department, objected to the two proposals to change the expressway—one to built a portion of the expressway below ground and another to eliminate a loop ramp at Chouteau Avenue which would eliminate the possibility of vehicles exiting the expressway on Chouteau Avenue to travel southward.[23] A later suggestion to move the path of the expressway to the east to avoid the Harris Row was similarly rebuked by highway department engineers, who, the Globe-Democrat wrote, argued that “the change in the route would make for dangerous curves and driving problems for motorists”.[24]

{Wood, Sue Ann. “North-South Distributor Road Controversy.” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, February 1, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 68.}

The implications of the Distributor delay fell beyond the immediate area as well. The Globe-Democrat wrote in 1972, “controversy over the proposed route of the North-South Distributor also has delayed construction of what would be a link between I-44 and I-55 and U.S. 40 and the downtown area.”[25] Traffic congestion on newly-built highways was already being partially blamed upon inaction regarding the Distributor.

Yet protest against the North-South Distributor was hardly without precedent. Venomous public reaction to another planned expressway that would cover Cole Street, Easton Avenue and Page Avenue likely played a significant part in that project never being realized. The Post-Dispatch wrote in 1968, “although it is only a dark series of dots on a map, the proposed Cole Street Expressway is becoming a center of a controversy that could affect urban renewal and Model City programs in St. Louis”.[26] The expressway in question, also known as the Page-Easton Expressway, would have stretched westward from Interstate 70 along Cole Street to Page Avenue and the City limits. It was assumed by many that it would later be extended by the county beyond the Inner Belt (now I-170) and Interstate 244 (now I-270).[27]

{Adams, Robert. “Cole Expressway: A Conflict of Interests.” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol 2. 6.}

Of course, traffic studies indicated a need for the expressway. At least two studies argued for the completion of the expressway, citing its location through one of the most dense residential areas as a major reason for the positioning of the project.[28]

The expressway proposal was met with the same sort of local criticism that had faced previous projects, but in a political climate that had irrevocably changed. Racial politics quickly entered the debate. “This [expressway] passes through the heart of the black area all the way,” argued Mattie Trice, then chairman of the Physical Development Committee of the Carr-Central Model City group, “the reason they chose this route is because the land is cheaper. But nobody cares what this may do to us. How many more people is this going to uproot?”[29] The uprooting of neighborhoods was familiar territory by this point, having been an inexorable product of highway construction from the beginning.

But we might consider that the political events of 1968, when this article was written, as having a profound impact on the relevance of race in conversations of neighborhood displacement. The year had already seen the nation reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, both champions of racial equity, and we must assume that the racial discourse was made profoundly more sensitive in light of these losses. It is not unreasonable to believe, then, that accusations of racial displacements were far more difficult to ignore in 1968 than they might have been a decade earlier. It is likely that general opinion did not believe this expressway to be a viable plan, as perhaps noted by its exclusion from a map of built and proposed expressways in the City published in the Post-Dispatch a month earlier.[30]

Another common denominator in discussions regarding expressways within the downtown area was the Pruitt-Igoe housing project along Cass Avenue between 22nd Street and Jefferson Avenue. Helen Floyd, chairman of the Project Advisory Committee for DeSoto-Carr, voiced concerns over the Page-Easton Expressway and the North-South Distributer as acting in tandem to cut the Pruitt-Igoe site from much of the City by binding it to the south and east by major impassable expressways.[31]

This concern, despite significant publicity in the late 1960s, was rendered largely mute by the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe in the years between 1972 and 1975, although the route of the expressway, once perhaps designed to service the site specifically, was not altered in light of Pruitt-Igoe’s decommissioning. The expansion of the route, however, north of Cole Street did seem to come on the heels of the beginning of Federal funding toward the “restoration” of the Pruitt-Igoe site, suggesting that the lack of housing boundaries in the immediate area might have been an opportunity for City planners to pursue the connection to Interstate 70 that had been originally desired.[32]

The debate over the North-South Distributor would surface just once more, in and around 1979, when a new set of public meetings was proposed around a final logistics and environmental review report conducted by Booker, Inc. Engineers. Booker released their report in September of 1979, submitting a revised version of the expressway that eliminated ramp access and frontage roads from the Lafayette Park area, allowing the expressway to avoid the Harris Row, and several suggestions toward building a more sensitive highway, ranging from limited cap treatments to sound and visual barriers to increased consideration of means by which to limit impacts on area schools.[33]

{Booker Incorporated Engineers, Architect & Planners. “Analysis of Selected Engineering and Environmental Factors, Route 755.” City of St. Louis, 1979.}

By now public support had galvanized against the expressway. Former Mayor Cervantes had sidestepped his 1971 promise to not build north of Cole Street, and angry residents from the north had organized with residents from the south, all of whom would be affected by the Distributor, to create the Coalition to Stop the North-South Distributor.[34] This group was made up of concerned citizens from Old North St. Louis, Hyde Park, Jeff VanderLou and Lafayette park, as well as housing advocacy and environmental groups.[35] Ultimately, Mayor James Conway would pin his legacy to the fortunes of the highway. Conway, who continued to be embattled by his support of the Distributor, was defeated in the 1980 mayoral election by Vincent Schoemehl, whose tenure would be marked by an interest in historical preservation and who had campaigned specifically on a promise not to build the expressway.[36]

The Booker Report, while failing to win over enough support to effect and finance the project, had significant implications for the future of highway development in the City. Firstly, in stark contradistinction with highway construction to this point, the Booker Report sought options that could make highways less obtrusive. Where the City had preferred raised highway construction, genuflecting to public concerns over accessibility only the extreme case of the I-70 stretch through the very central and historic downtown area, the Booker Report outlined several areas of sensitivity.

[slideshow_deploy id=’191817′]

These ranged from simple to complex interventions. For the most southerly section, between the southerly terminus at I-44 and Chouteau Avenue, Booker recommended a series of typical strategies—walls, trees and berms—for sound abatement. From Chouteau Avenue north to Highway 40 (now I-64), the expressway would be elevated and have no special treatment. The expressway would continue at grade until Cole Street, receiving only planting treatments. North of this point to the northerly terminus at I-70, the expressway would receive considerable treatment of berms, walls and plantings for both noise mitigation and visual aesthetics.[37]

Booker endorsed a range of methods for noise control, visual aesthetics and safety and accessibility issues. It is difficult to believe that such detailed interest could economically be inserted into such treatments without a consideration of the impacts of previous highway construction, particularly that so devoid of the treatments now being espoused.

Booker’s responses suggest an adjustment to adverse reaction to the first iteration of highways in the City, such as the relentless imposition of the Mark Twain Expressway over Old North St. Louis, which literally cut away the civic center of the neighborhood from his historical boundaries without so much as an attempt at visual or auditory subtlety.[38] In the approximate decade between the construction of the City’s major highways and the planning of the North-South Distributor, we see a palpable shift in thinking as it relates to the expressway’s relationship with the City and land around it.

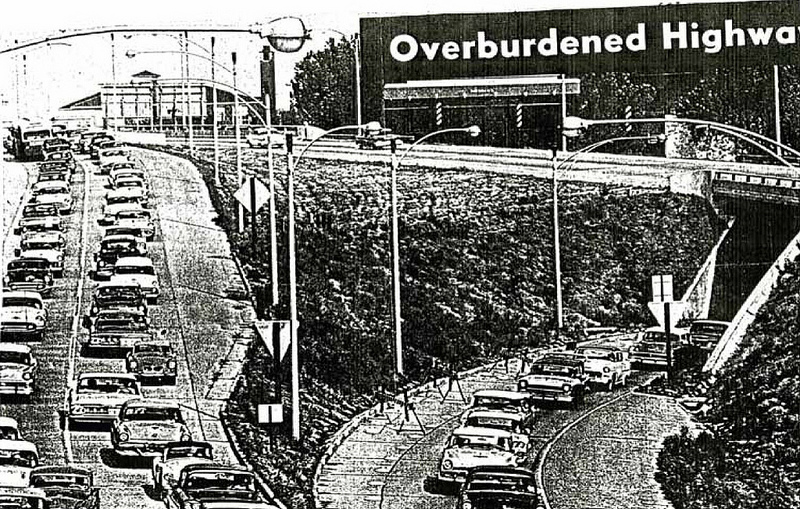

Despite this shift in public opinion toward major expressways since the time of the construction of most of St. Louis’ arterial infrastructure, it is important to remember that in the 1950s and 60s, there was significant belief that additional roadways were needed. Readers of the Post-Dispatch, for example, opened their newspapers in late 1959 to see an image of gridlock on a recent expressway under the demanding caption “Overburdened Highways”, a visual reminder that traffic need was far from being satisfied by the current infrastructure .[39]

{“Overburdened Highways.” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, September 20, 1959. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 48.}

The article would go on to support the widening of the Red Feather Express Highway from four lanes to six, and further blames the Board of Alderman for not passing the necessary legislation to allow the State Highway Department to begin the construction. Given that a special election on the issue would go before voters two months later, the Post-Dispatch’s clear bias toward further expressway construction is notable.[40]

Politicians quickly weighed in on the matter as well. “It appears that we’re getting further behind all the time in trying to solve these traffic problems in the metropolitan area,” commented Representative Stephen Burns of the Forty Second District in 1969, adding, “as one of my constituents put it, we have some of the longest parking lots in the world.”[41]

The need for a general expansion of vehicular arteries in this country—from road widenings to the construction of highways and Federal interstates—continues to be predicated upon the assumption of a limitless propagation of vehicular traffic. Even as early as 1969, in the earliest years following the completion of the City’s major highways, Highway Department Engineer James Roberts lamented—without, it seems, a sense of irony—“these highways, particularly the Daniel Boone Expressway… are too small,” adding, “there’s just not enough capacity.”[42] Discussions of the need to widen the highways were tragically immediate.

The fundamental root of Roberts’ concern was not that the City was failing to build roads fast enough, but that each road built instead engendered even more traffic. E. Michael Jones later wrote on what he terms “traffic generation”, pointedly arguing, “the automobile as a form of mass transportation is a self-defeating proposition. The more the culture builds roads and bridges and parking lots to accommodate the automobile, the more it creates the very traffic it attempts to alleviate.”[43] Given the extreme dynamics facing urbanism between the 1940s and the present, it is somewhat difficult to pin traffic increase entirely upon arterial expansion, but Jones is correct to note that it did allow for more cars, as well as a more mobile citizen base that could commute from the County to the City.

This ability to move freely in and out of the City inevitably put more cars on the roads, and for longer distances. Further, the increase in automobiles, artificially empowered by road expansion, would plague the City center with more parked cars than it had space and facilities to handle. “No matter how hard it tried,” concludes Lovelace, “the highway (and major street) delivery system could not keep up with the needs brought about by the increasing numbers of trucks and automobiles.”[44]

These lessons in mind, it is perhaps surprising to hear the idea of the Distributor has re-emerged in recent years. The Missouri Department of Transportation has continued interest in developing a north-south distribution route, and has recently undertaken a study of the built Distributor interchange at Highway 40/Interstate 64, for a project now referred to as the 22nd Street Parkway, assuming perhaps that the moniker “North-South Distributor” is too poisonous for continued use.[45]

Additionally, there is evidence that developer Paul McKee of McEagle Properties has considered using such a distributor as a key access point as part of his controversial masterplan for the redevelopment of the northside of the City.[46] The New Mississippi River Bridge project, which broke ground in April of 2010, intends to join Interestate 70 on both sides of the River without running it through downtown St. Louis.[47] This project, while never directly stating a need or proposal for a distributor route, would likely effect the closure of the downtown I-70 underpass, removing the only north-south expressway route across the downtown area.

The North-South Distributor-cum-22nd Street Parkway could be in a key position to connect I-70 to I-64, I-44 and I-55. Whether this project is realized as a result of the New Mississippi River Bridge Project is conjecture at this point. Mayor Cervantes in 1972 declared that the Distributor would be the last major expressway in the City, and while this did not ultimately turn out to be the case, we should note that no major expressways have been constructed within City limits between that time and the groundbreaking of the Bridge in 2010. We may be looking at a political climate that is more sensitive to the construction of a north-south route, but the City and planners should consider the lessons learned from the North-South Distributor in future planning.

Ultimately, the demise of the North-South Distributor cannot be pinned to any single source. It is more reasonable to believe that it was done in by a combination of political savvy by several groups and public figures, civic protest and a general but unmistakable lack of sufficient funding. The ability of citizen protest to stall a project of such scale is certainly questionable. Darayus Kolah, in a 1981 Masters thesis, skeptically writes, “the arguments brought out by groups opposing the proposed Route 755 were not very strong or valid points when examined in detail.”[48] Others, such as the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group, are more sensitive to the impacts upon displaced residents.[49]

The designation of the Lafayette Park area as historic was a far more effective means of stalling the Distributor, regardless of whether or not specific preservationist interest groups actually participated in getting Federal historic protection for the area. But it would be an oversimplification to omit matters of funding from the conversation. Certainly the withdrawal of Federal funding as a result of the National Register distinction was impactful. Mayor Schoemehl would inherit a City that was, in his words, “broke” and in “a financial challenge the likes of which we have not seen since” in 1981 when he came into power.[50] We can easily believe that funding a massive public works project, without significant Federal support, was politically anathema, financially impossible and unpopular among many taxpayers in the City.

In many ways, then, the demise of the North-South Distributor was actually the last gasps of an era of major urban public works. But importantly it was also a beginning of a more careful consideration of public works upon the populace of the City, not merely those served by arterial expansion but also those who would be indirectly affected by it through home relocation, demolition or proximity to large, noisy and dangerous pieces of infrastructure. We can see, through the evolution and ultimate demise of the North-South Distributor, an indelible advance in how our society views the urban expressway.

This essay was written in 2010 under the guidance of professors Eric Mumford and Margaret Garb as part of the requirements for Master of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis. Special thanks to the Missouri Historical Society for access to their archives.

[1] Booker, Incorporated Engineers, Architects & Planners, “Analysis of Selected Engineering and Environmental Factors, Route 755,” 1979. 1.

[2] “3 Superhighways Planned for Postwar St. Louis,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 3, 1943. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Clippings, Vol. 9.

[3] Harland Bartholomew, Comprehensive City Plan: Saint Louis, Missouri, 1947, Plate No. 20.

[4] Eldridge Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew: His Contributions to American Urban Planning (Urbana, University of Illinois Office of Printing Services, 1992), 119.

[5] Harland Bartholomew, Comprehensive City Plan: Saint Louis, Missouri, 1947, 40.

[6] Joshua Burbridge, “The Veering Path of Progress: Politics, Race, and Consensus in the North St. Louis Mark Twain Expressway Fight, 1950-1956” (Masters Thesis, Saint Louis University, 2009), 53-54.

[7] Joshua Burbridge, “The Veering Path of Progress: Politics, Race, and Consensus in the North St. Louis Mark Twain Expressway Fight, 1950-1956” (Masters Thesis, Saint Louis University, 2009), 54.

[8] ibid

[9] “Progress Report on Area Road Building,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 9.

[10] Sally Thran, “Distributor Road May Extend North Of Cole Street”, Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[11] Darayus Kolah, “Route 755: Highway Impact on a St. Louis Neighborhood” (Masters Thesis, Washington University, 1981), 7-8.

[12] ibid 9.

[13] ibid, 9.; Sue Ann Wood, “North-South Distributor road controversy,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, February 1, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 67.

[14] Darayus Kolah, “Route 755: Highway Impact on a St. Louis Neighborhood” (Masters Thesis, Washington University, 1981), 9.

[15] Miranda Rectenwald & Andrew Hurley, From Village to Neighborhood: A History of Old North St. Louis (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2004). 81.

[16] Sally Thran, “Distributor Road May Extend North Of Cole Street”, Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[17] Sue Ann Wood, “North-South Distributor road controversy,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, February 1, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 67.

[18] ibid; “Some wonder if highway will be built,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 72.

[19] “Some wonder if highway will be built,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 72.

[20] Sally Thran, “Distributor Road May Extend North Of Cole Street”, Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[21] “Some wonder if highway will be built,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 72.

[22] ibid

[23] Sue Ann Wood, “North-South Distributor road controversy,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, February 1, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 67.

[24] “Some wonder if highway will be built,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, 1973. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 72.

[25] “I-44 Race To A Bottleneck,” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, December 2-3, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 78.

[26] Robert Adams, “Cole Expressway: A Conflict of Interests,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 6.

[27] ibid

[28] ibid

[29] Robert Adams, “Cole Expressway: A Conflict of Interests,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 6.

[30] “Progress Report on Area Road Building,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 9.

[31] Robert Adams, “Cole Expressway: A Conflict of Interests,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1968. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 6.

[32] Sally Thran, “Distributor Road May Extend North Of Cole Street”, Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[33] Booker, Incorporated Engineers, Architects & Planners, “Analysis of Selected Engineering and Environmental Factors, Route 755,” 1979.

[34] Sally Thran, “Distributor Road May Extend North Of Cole Street”, Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1972. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[35] Miranda Rectenwald & Andrew Hurley, From Village to Neighborhood: A History of Old North St. Louis (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2004). 85.

[36] Saint Louis Public Library, “St. Louis Mayors”, 2001. <http://exhibits.slpl.org/mayors/data/dt45974379.asp>; Miranda Rectenwald & Andrew Hurley, From Village to Neighborhood: A History of Old North St. Louis, 2004. 85.

[37] Booker, Incorporated Engineers, Architects & Planners, “Analysis of Selected Engineering and Environmental Factors, Route 755,” 1979. Figure 2.

[38] Miranda Rectenwald & Andrew Hurley, From Village to Neighborhood: A History of Old North St. Louis (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2004). 82.

[39] “Overburdened Highways,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, September 20 , 1959. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 48.

[40] ibid

[41] John M. McGuire, “[full title omitted] Forsees Road Restrictions,” Saint-Louis Post-Dispatch, September 9, 1969. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[42] John M. McGuire, “[full title omitted] Forsees Road Restrictions,” Saint-Louis Post-Dispatch, September 9, 1969. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Streets & Roads Scrapbook, Vol. 2. 77.

[43] E. Michael Jones, The Slaughter of Cities: Urban Renewal as Ethnic Cleansing, (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2004). 197.

[44] Eldridge Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew: His Contributions to American Urban Planning (Urbana, University of Illinois Office of Printing Services, 1992), 121.

[45] Missouri Department of Transportation, “22nd Street Interchange”, <http://modot.org/stlouis/major_projects/22ndstreetinterchange.htm>.

[46] Eric Friedman, personal conversation

[47] Ken Leiser, “Illinois, Missouri break ‘ground’ on new river bridge,” Saint Louis Post-Dispatch, April 19, 2010, <http://interact.stltoday.com/blogzone/along-for-the-ride/along-for-the-ride/2010/04/illinois-missouri-break-ground-on-new-river-bridge/>.

[48] Darayus Darayus Kolah, “Route 755: Highway Impact on a St. Louis Neighborhood” (Masters Thesis, Washington University, 1981), 2.

[49] Miranda Rectenwald & Andrew Hurley, From Village to Neighborhood: A History of Old North St. Louis (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2004). 82-83.

[50] Vincent Schoemehl, Interview with MayorSlay.com, April 17, 2006. <http://www.mayorslay.com/podcasts/display.asp?podID=44>.

*this post first appeared at GUMBULLY.com, a young design collective formed in 2013 and based in Austin, Texas